Ahead of her solo presentation at NADA with LA-based gallery Moskowitz Bayse, the artist sits down with Document’s editor-in-chief to discuss surveillance data as artistic material

In Michel Foucault’s concept of the panopticon, the government holds an omnipresent, all-seeing gaze through which it exerts power both via surveillance and data collection. To survive, individuals must self-regulate their actions in accordance with authority. In her first solo show at New York’s New Art Dealers Alliance fair (NADA) comprising three photographic series, New York-based multimedia artist Julia Weist expands this concept by accessing the very data the panopticon thrives on.

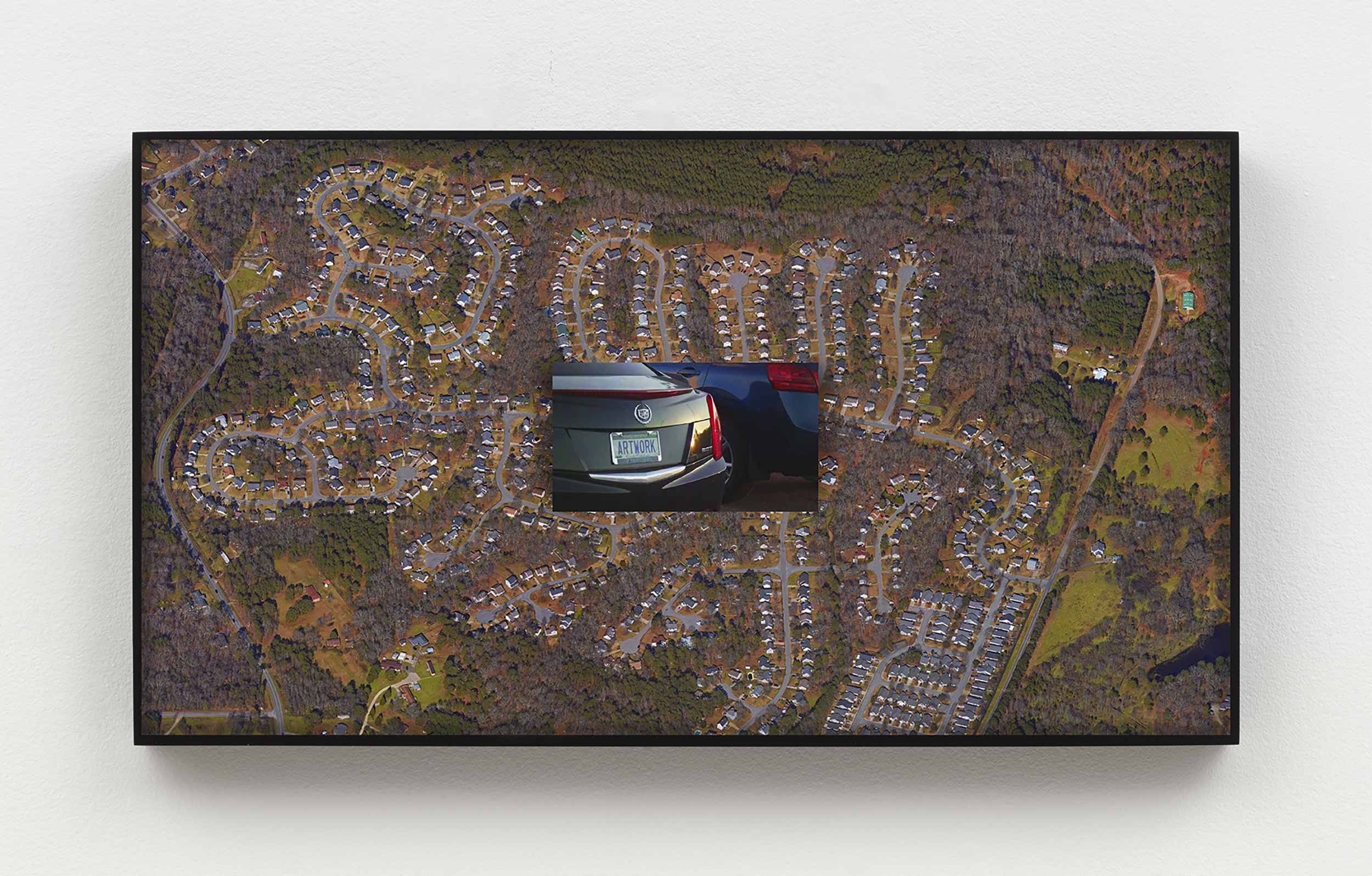

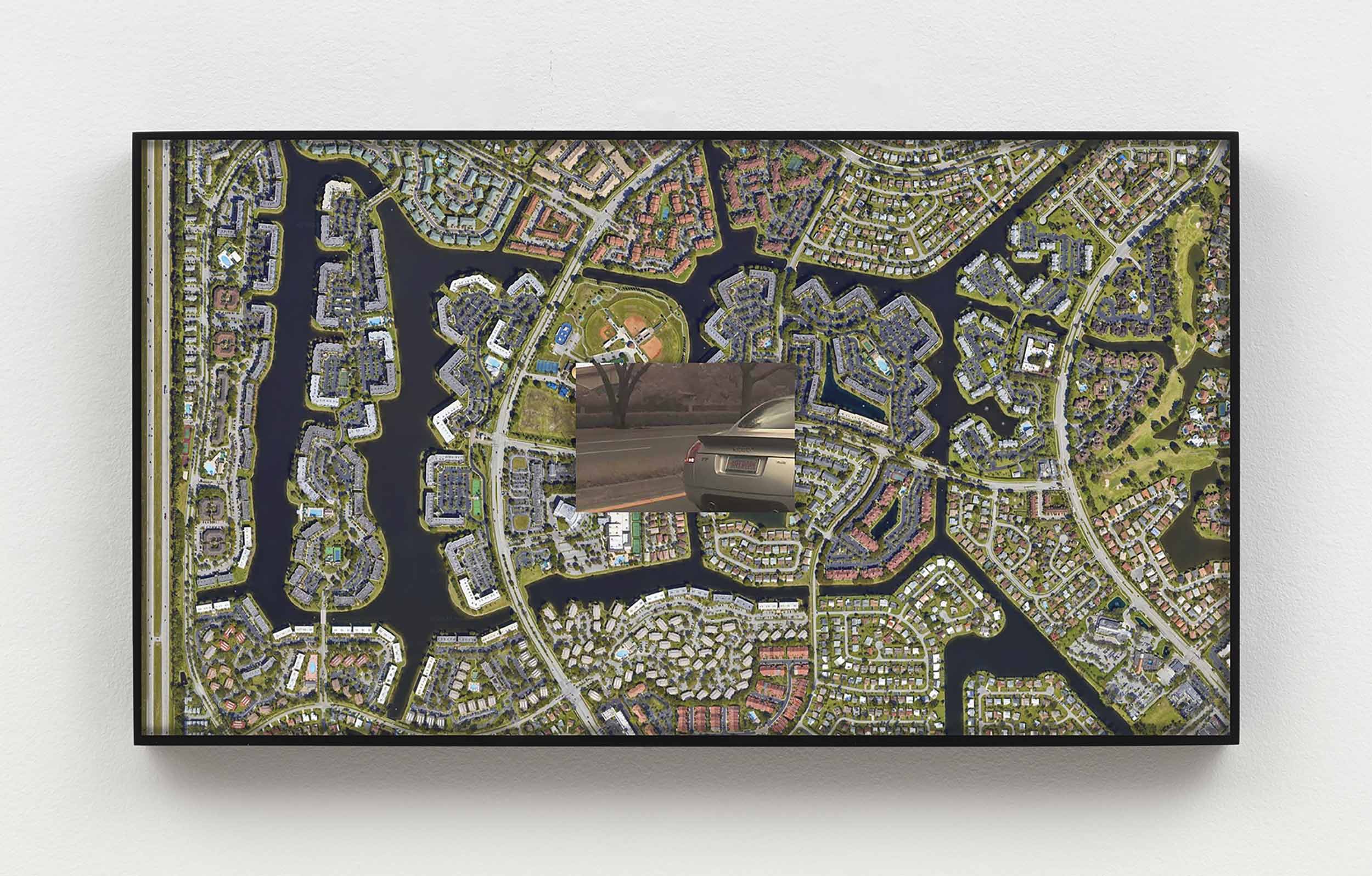

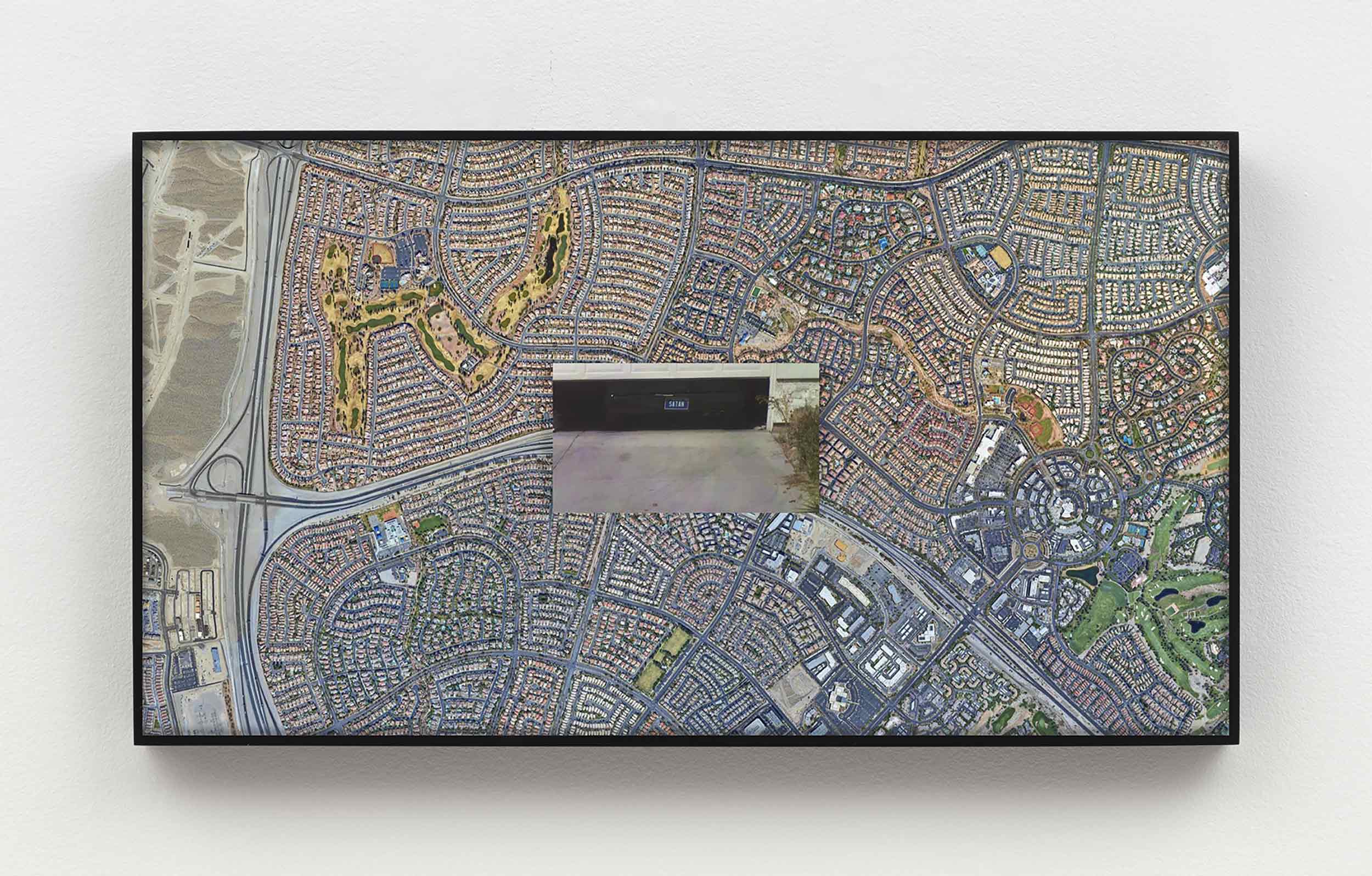

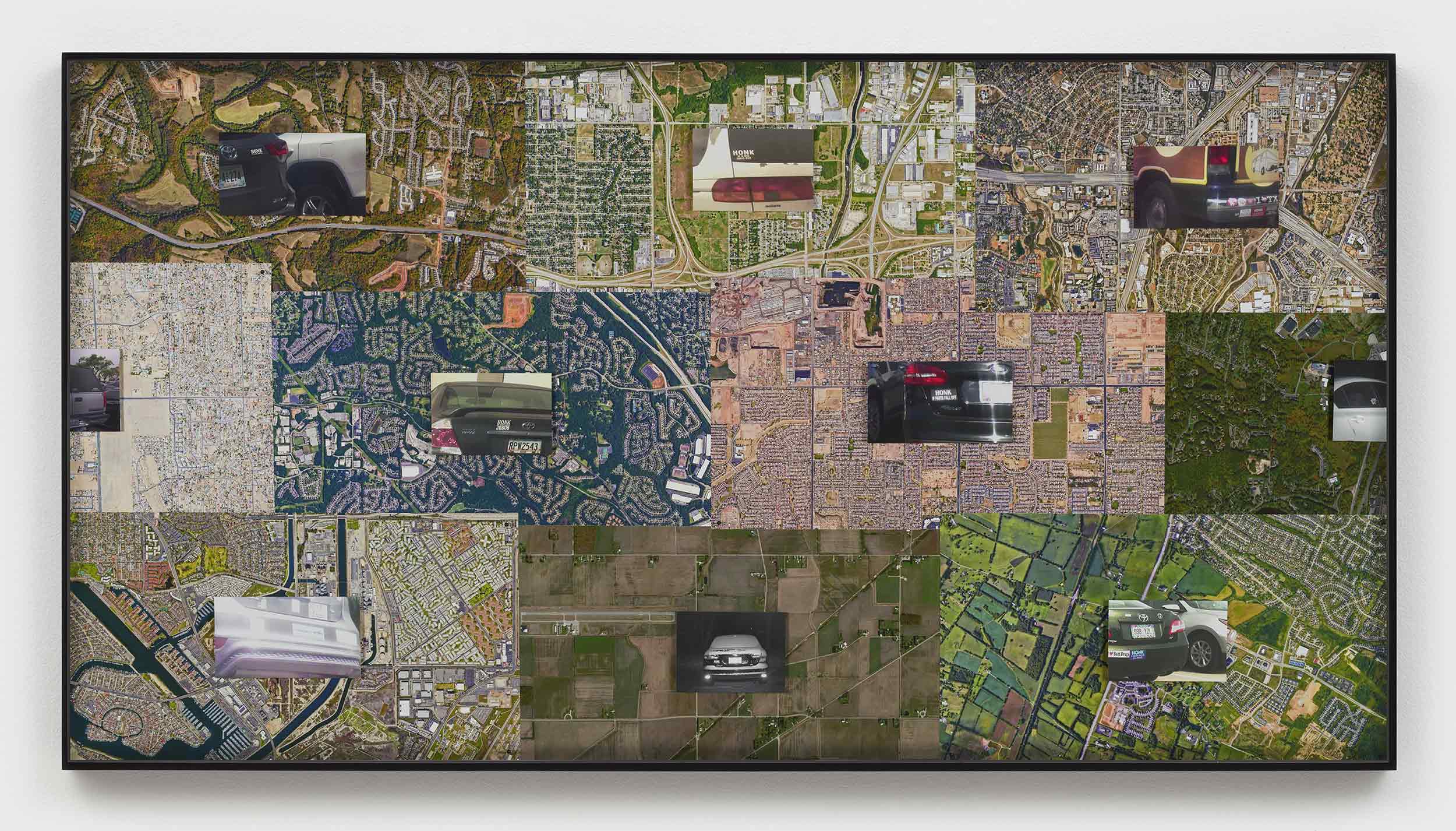

As a private investigator—a license application the artist never thought would be approved—Weist uses the caches of media available to her as source material for her art. In her series on display at NADA, Weist mined a database of license plate images used to track vehicles, finding absurd motifs among the nearly endless archive. The resulting body of work is an assemblage of images that reveal a paradox; while the publicly-accessible archives grow exponentially, control over information becomes increasingly privatized because of corporate interest. As a sign behind a parked car in one of Weist’s images reads: “where is the public?”

In Self-Portrait (from the series Vehicle Sightings), Weist catches herself being surveilled. The image shows her sitting on a street curb, arms loosely crossed, staring off into the distance, seemingly blind to the fact that she’s been caught on camera. Despite the access that being a private investigator affords, the artist remains constantly aware that the subversive nature of her work could someday jeopardize her license. This self-consciousness materializes as a vulnerability within her work, reminding us that no one is safe. Yet amid the headache-inducing weight of the power systems she wrestles with in her art, a sense of brevity prevails. One piece in the exhibition shows a compilation of images of cars whose bumpers display the word “honk” against a satellite backdrop. For Weist, this lightheartedness is a crucial entrypoint to our hearts and minds, and the first step towards a paradigm shift.

Nick Vogelson: First of all, congratulations on your first solo show with NADA. Tell me about the three series you are presenting.

Julia Weist: This body of work has been in development for a long time, and this is actually the very first moment that I’m sharing it publicly. I applied two and a half years ago to be a licensed private investigator in New York State—which is a really extensive process for good reason. Once approved, you have extraordinary access to what they call ‘sensitive private information’ about fellow Americans. I did not anticipate I would be approved, but through a public art commission I received a large-scale government contract to do research and this allowed me to pass a very rigorous process and get licensed. The work that I’m sharing at NADA is all made with the access I was able to achieve once I went through this system.

Nick: Your work talks a lot about the investigative process. How did you arrive at connecting the investigative process with a creative process?

Julia: There are two worlds within the material that I had access to through this project—one is very text heavy, and one is very visual. What’s on view at NADA is the content that’s primarily visual. And in a lot of my work, I approach archives as sites of material. So whereas an artist might use a textile or wood or metal as a material, I tend to look at the trove of media that’s accessible through collections of this sort as raw material for production. The work that we’re talking about today is made from a massive trove of billions of images that are very disturbing and very powerful. This cache is not accessible to anyone who does not meet certain qualifications. So it’s a very natural process for me to try to share that with others, because I feel like these are images that need to be seen.

Nick: In your work, you talk about systems of power and what those processes look like. Could you talk a little bit more about that?

Julia: Several of the series in this body of work try to look at the question of authority, and what one can do to try to dismantle or confront authority. In many ways, authority is a very practical power—there are resources and privileges that people, such as those in law enforcement, have in our society as state-protected actors with power over others. But in some ways, authority is also a concept, and it relies on people respecting that concept, outside of the violent practical side of authoritarian action. In several of the pieces that we’re showing, I’m trying to think about what could be conceptually disarming to people with the authority to surveil others. What I settled on for several of the works was something that would make these individuals feel foolish. There’s an image of an intervention that I made that was then sucked into the surveillance system that tracks cars. I was just imagining what you could do to a car that would make the person looking on the other end feel the most foolish in their position of authority. It’s a tutu on a Subaru. The car has dressed for its encounter with the gaze of an unseen surveillant. That gesture is a kind of absurdity that to me feels productively disarming in its context.

Nick: What does it mean to engage with the public space in the age of infinite content? Is it about surveillance or public access? Where do you start in your mind when you start thinking about these things?

Julia: There’s one work that I think speaks to this really specifically. It’s an image, again, appropriated from a surveillance database that shows a physical intervention that I set up in public space next to a vehicle. I accessed the image by running the license plate of the vehicle directly next to the intervention. It’s simply a handmade sign that reads ‘Where is the public? Which, of course, the purpose of this database is to locate members of the public and find their longitudes and latitudes at different time stamped intervals. But it’s also a larger conceptual framework for the work as a whole, asking: where are the commons? We used to understand things that were shared resources, things like air and water as being part of the commons. Now, we know those resources have been increasingly privatized by corporations. For example, who is controlling the water supply? I think it’s an equally valid question when it comes to a digital landscape. Where is the line between what is considered this ‘sensitive personal information’ that’s given to some and not others? That’s collected and sold? Have we really caught up both in terms of legal frameworks and also cultural frameworks for understanding who owns a surveillance image? And who has a right to preserve and circulate content that implicates or documents a community that’s not privy to that system?

Nick: So in a way, it also shows all of our vulnerability?

Julia: Absolutely. I think that the vulnerability really comes from not knowing that these systems are operating. In a body of work that I’ll be showing in the larger solo exhibition that will take place in September, there is a piece that documents data on myself taken from a database called The Work Number that tracks payroll information over decades. I was able to find out how much money I made in a two week pay period at a job that I had more than 20 years ago. That data was collected, preserved and then sold to those with access. We are most vulnerable when we don’t even know that this is happening. Because, for example, there are legal frameworks where I can freeze that data so that others, for example future potential employers, can’t access the information. That right is only useful if I know I have it and I would say that most Americans have no idea that this system exists. So if you’re reading this and you want to freeze this data, just Google ‘The Work Number data freeze.’ You can intervene in this system by exercising your right to control the information about you.

“I’m worried that America is numb and that we are getting increasingly skilled at filtering out things that are dark or have implications for our own life that we’re not ready to feel settled about.”

Nick: Your practice operates on the level of exposing these levels of surveillance that we might not be aware of. Certainly we are aware of CCTV cameras, and browser searches in all of our databases online being tracked, but what you’re saying is you’re opening the door to the level of surveillance and digital databases that the average person might not be aware of.

Julia: Exactly, and it’s actually not just digital. So when you’re at a mall, and you drop your business card in a bowl to win a free car, if you’ve ever wondered what the economics of those sweepstakes are, it’s that all of those business cards are transcribed or scanned and packaged and sold as information about people’s job titles, addresses, and telephone numbers—that more than pays for the car that they’re giving away. So it’s not purely in a digital space. But of course, the data is trafficked through databases.

Nick: So it’s actually through surveillance offline, really, and how it ends up materializing online. For example, a payroll database from 20 years ago, which is ostensibly not what you think of as online tracking?

Julia: Yes and I think in the popular imagination, Americans are most worried about the fact that they get Instagram ads for the most highly specific things that they’re speaking about when their phone is near. And absolutely, that is pernicious and terrifying. But it’s actually, I think, one of the less potent evils of the surveillance state, because there are federal laws protecting that information being tied to your real name and address, your social security number, your personal information. What is more of a liability for people are things that are connected to their real name and address because that data can prevent people from getting car insurance, housing, or a job. So those are the things that I’m trying to highlight in this work, because they’re not as well understood, and therefore not as commonly feared.

Nick: There is a very serious connotation about the surveillance state, but there’s also a humor in it, especially about what one could argue is the mundaneness of some of the images. Can you speak to that a little bit?

Julia: I’m worried that America is numb and that we are getting increasingly skilled at filtering out things that are dark or have implications for our own life that we’re not ready to feel settled about. My friend and colleague, artist Maggie Hazen has a phrase that I think is really apt here and that she uses in the context of her anti-carceral work, which is “seduce and disarm.” Sometimes, in order to move someone, you have to pull them in first to get the engagement that’s necessary to reach them through the numbness. And I think that can be done by taking what could seem at first glance as a light hearted approach—for example, the piece that’s looking at surveillance images of bumper stickers that start with the word “honk.” At first glance, you think: I’m looking at some funny bumper stickers, but it’s the banality and seeming lightheartedness of it that underscores that this tracking is in every area of our life. Even places that seem innocuous are entrapped within these larger systems.

Nick: As my last question, I want to go back to the beginning of the process where you quite literally thought you would be putting yourself on trial to get the private investigator license, and as part of that process, there’s another layer to read—you did the work that you might not even have been able to access to begin with. Could you speak to that a little bit?

Julia: Yeah, so I think it’s still a possibility that I might lose this license, because although I’m following every single requirement to the letter of the law, these works are not in the spirit of the law. And I think that there is a scenario where the Department of State takes issue with my general approach to the practice of private investigation. But I do feel that the power of the work I’ve made is in following the rules, and showing that even when you follow the rules so closely and so precisely, there are still huge issues that are not covered through legal protections. And that’s something that I feel very urgently I need to emphasize through this work.

Weist’s work is on display at NADA New York, May 2–5. She will present her first solo exhibition with the LA-based gallery Moskowitz Bayse in September 2024.