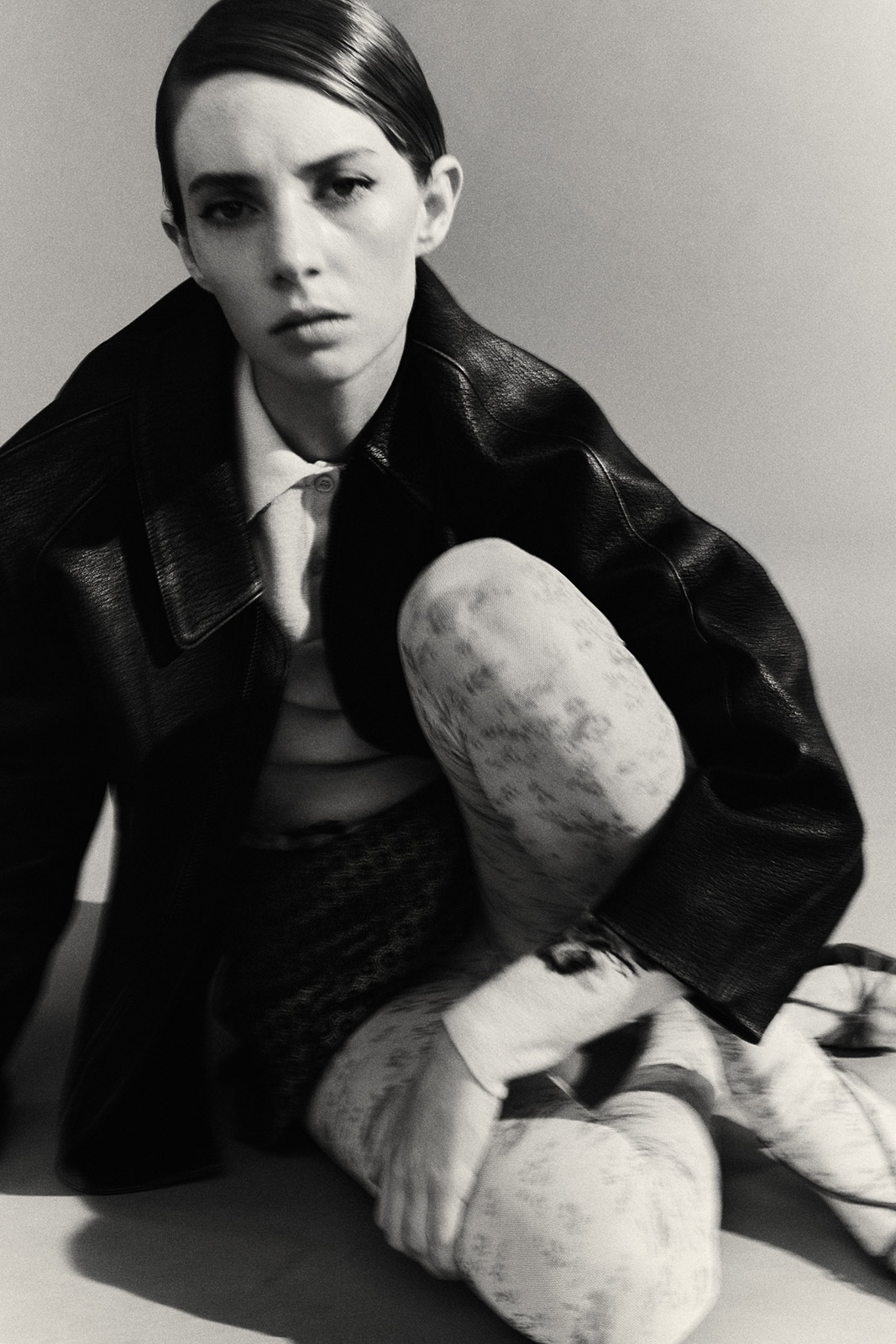

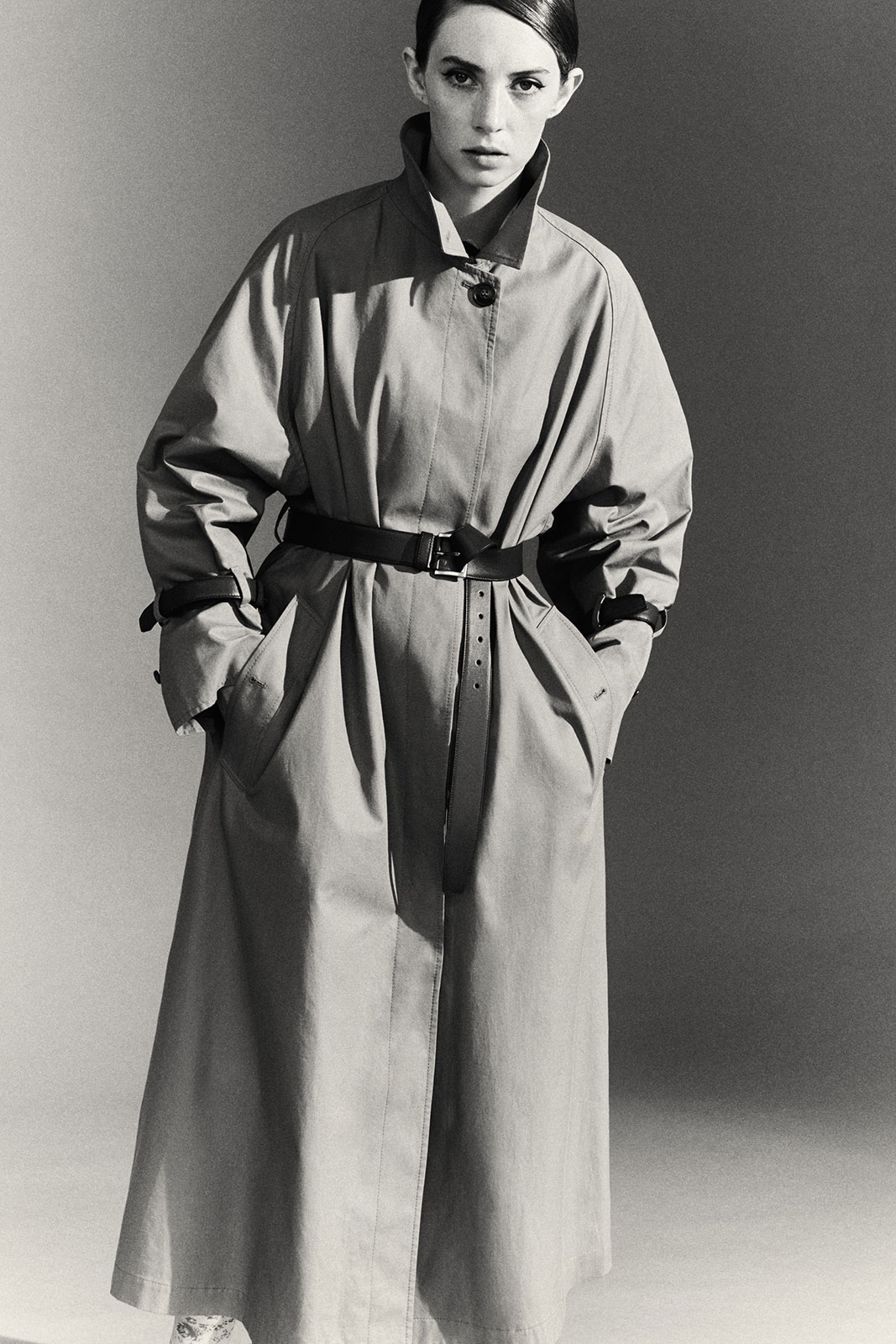

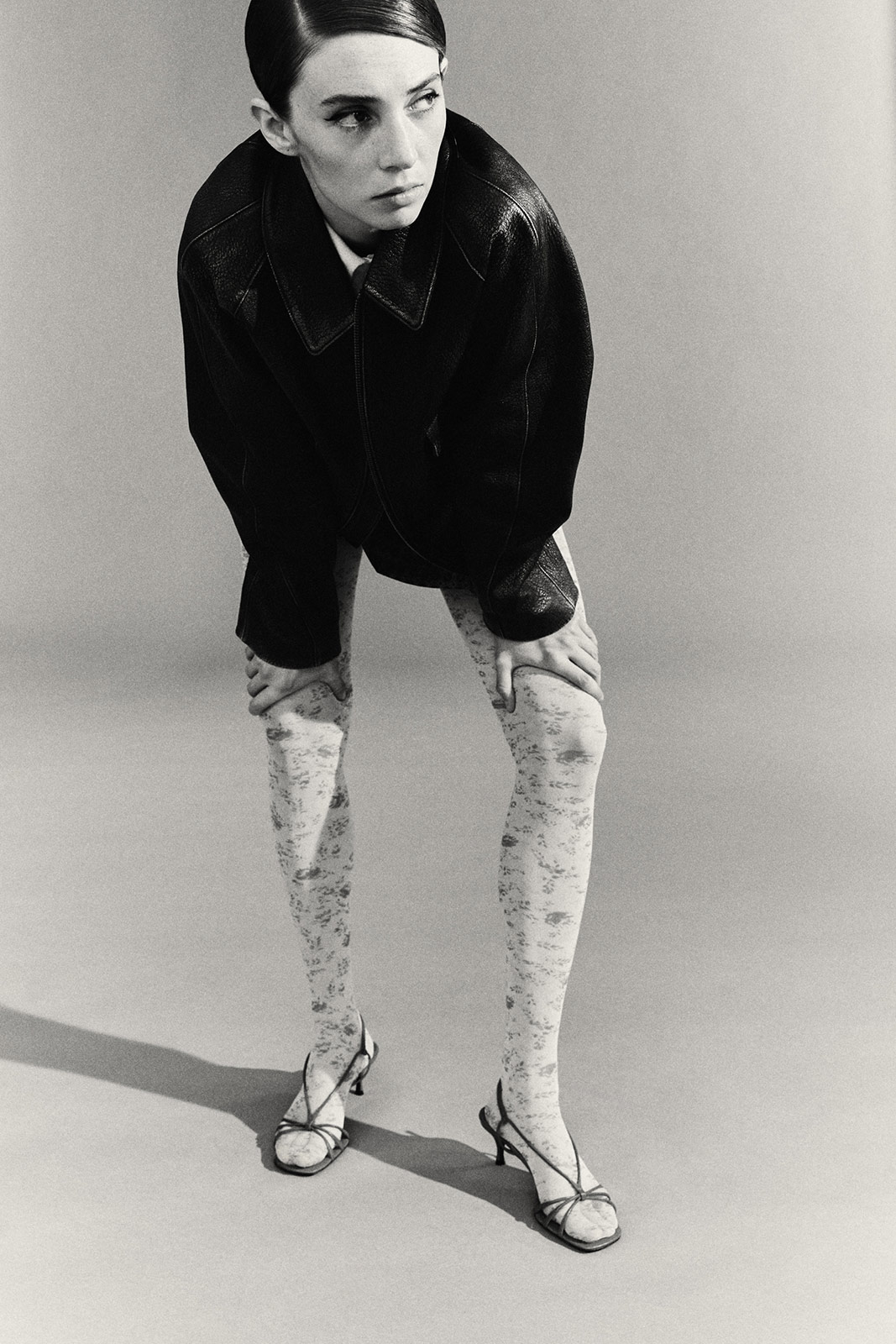

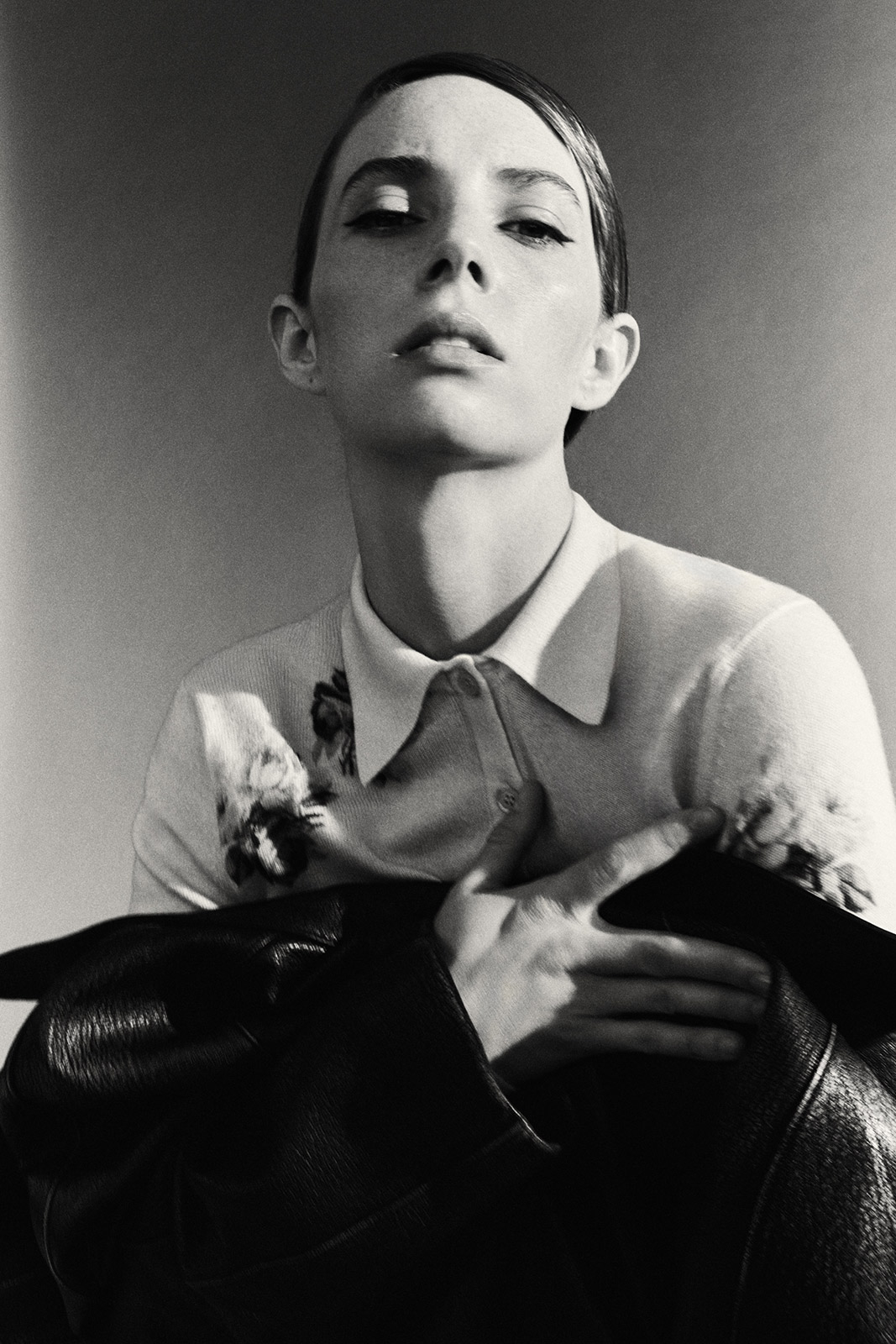

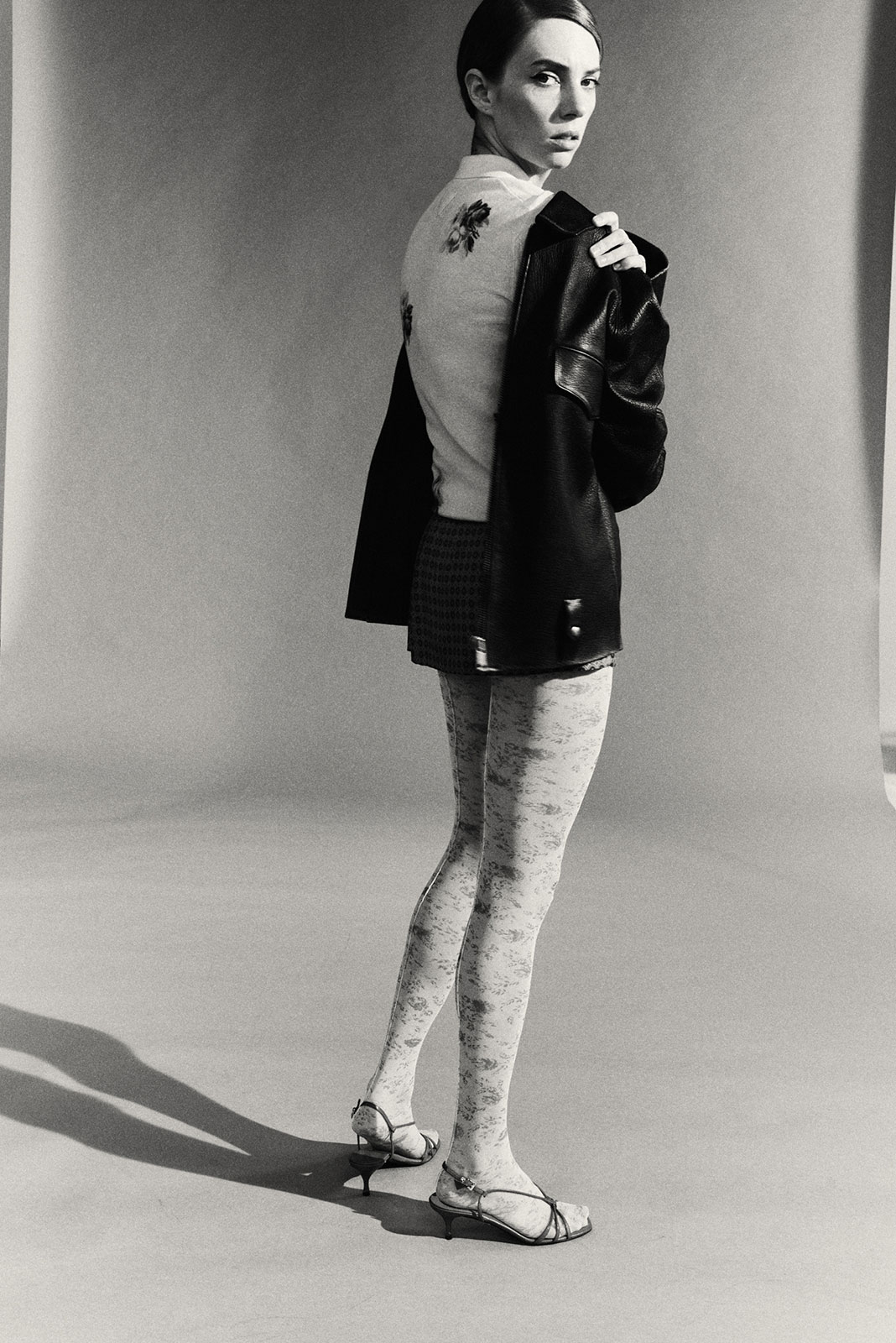

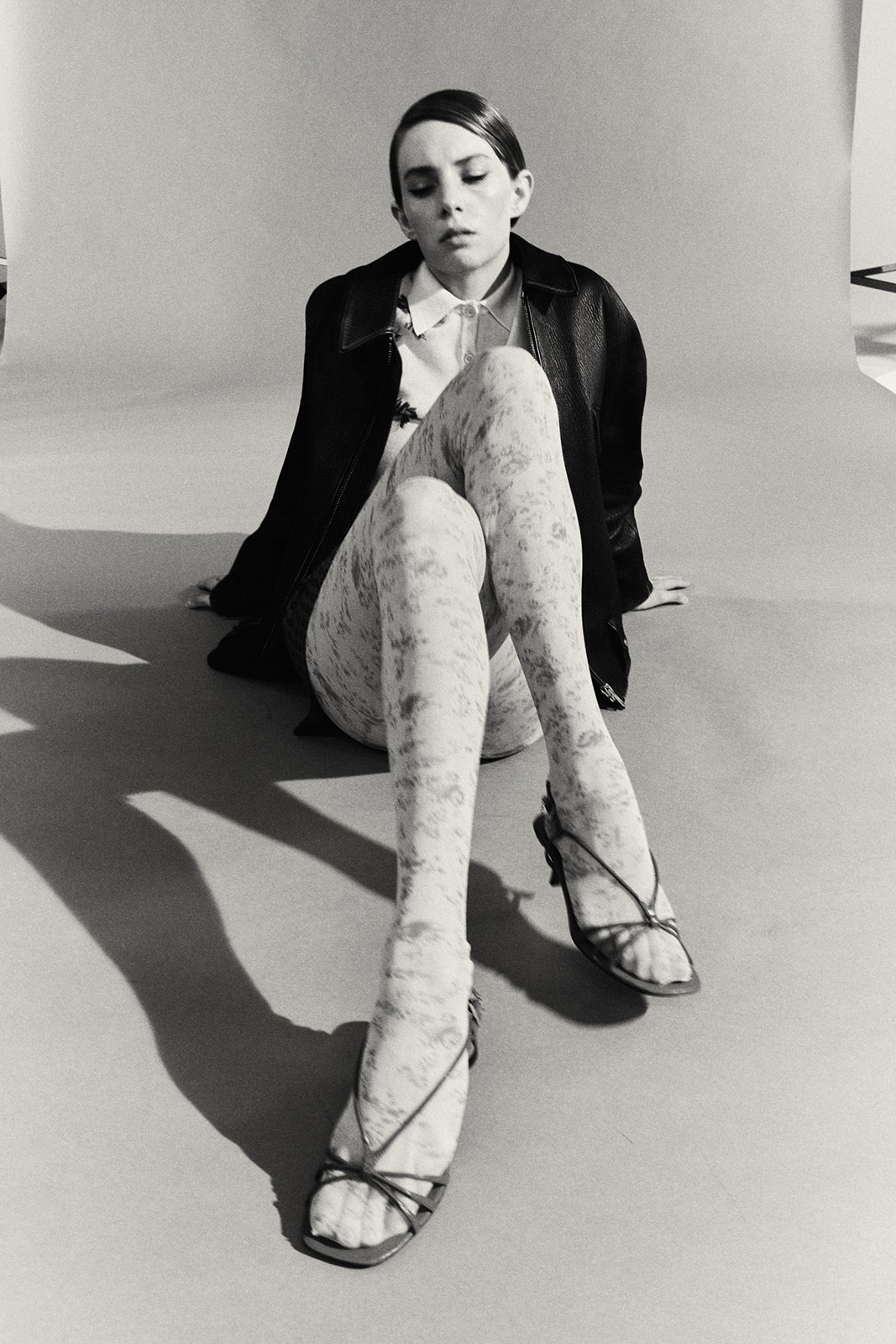

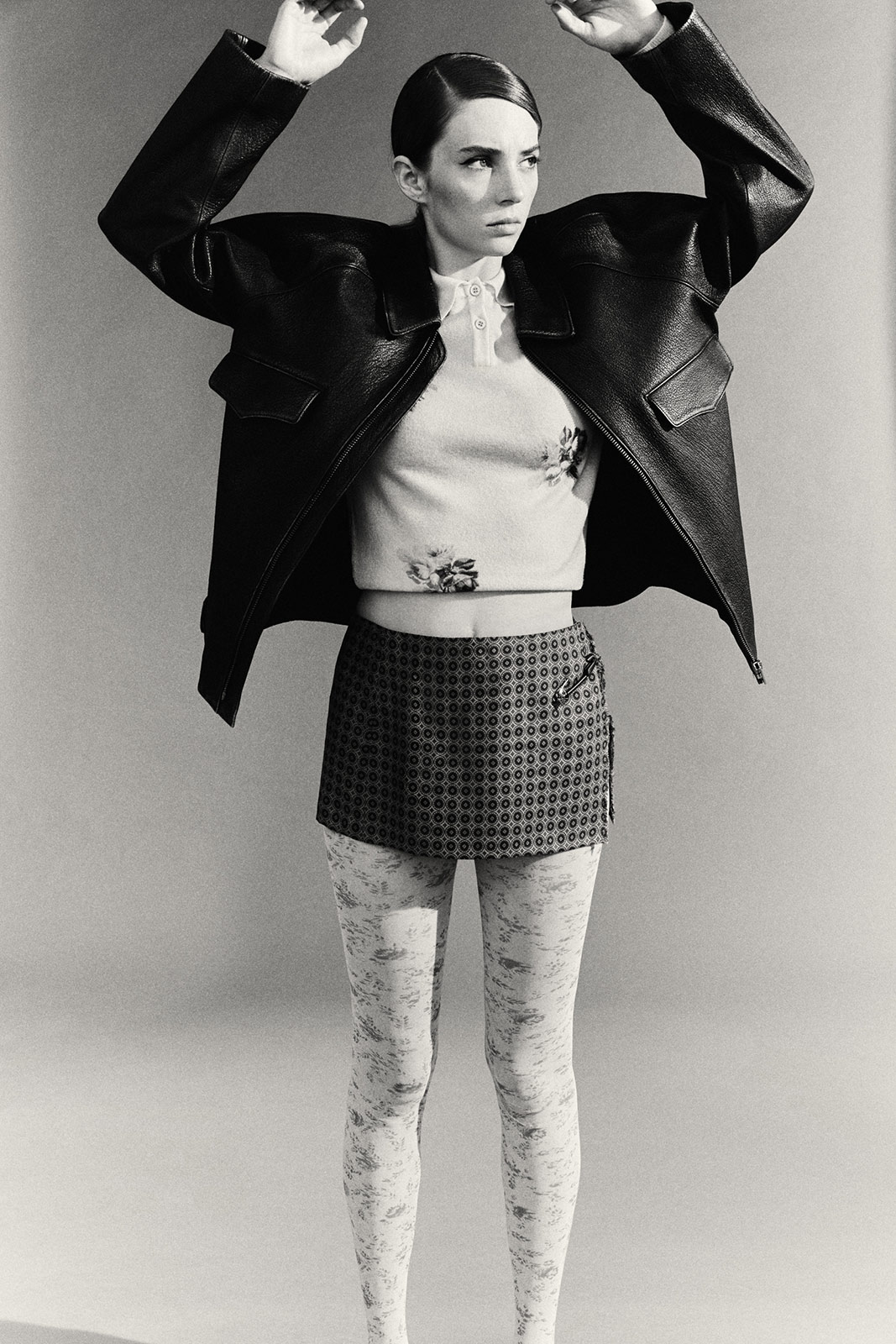

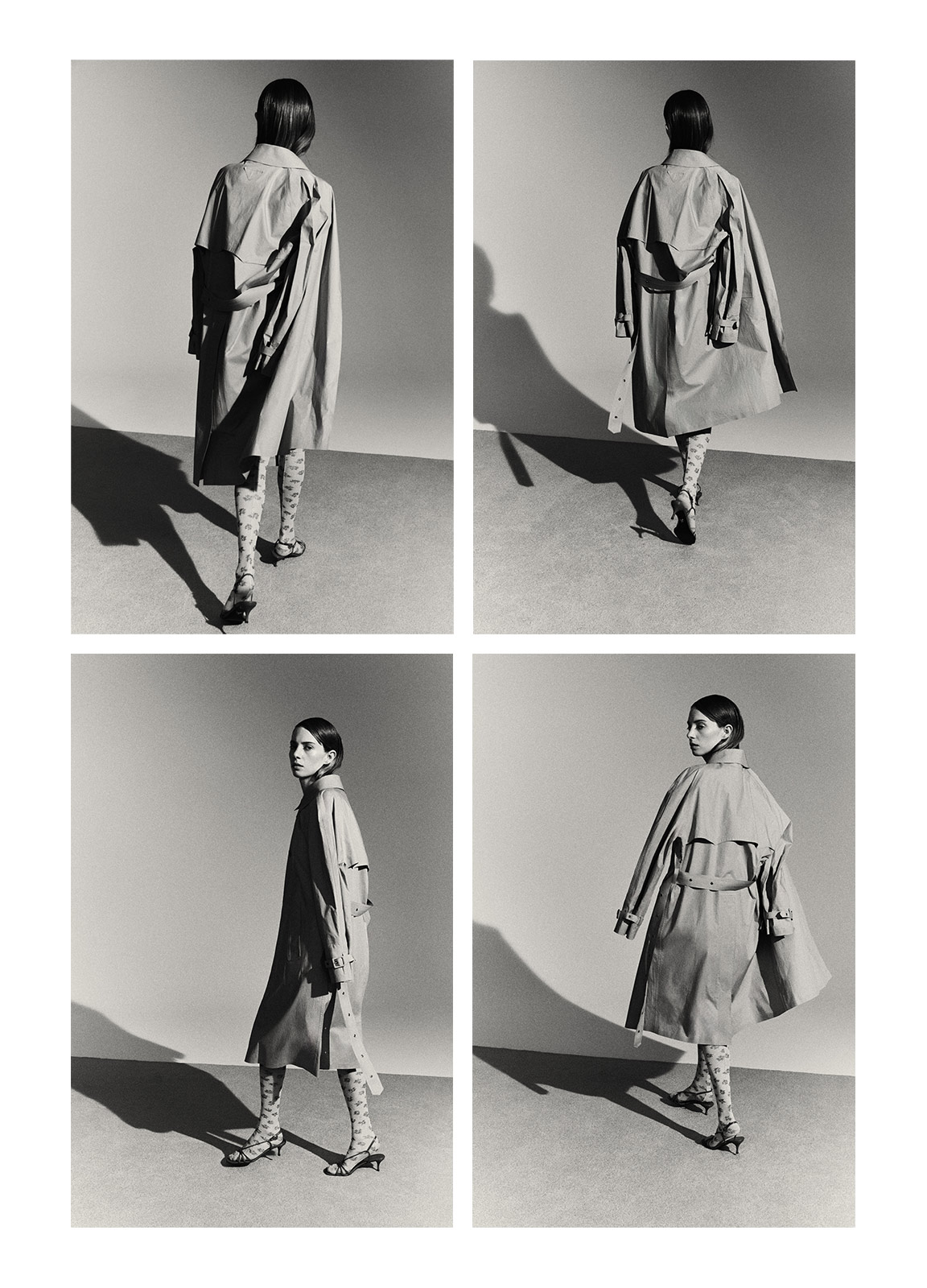

The multidisciplinary artists untangle lyric metaphors and pop cultural myths for Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue

Maya Hawke is being kidnapped from her bed. Her captors strap her to a chair and place a silver space-age helmet, with primary-color wires dangling, on her head. A wall of clunky pre-plasma-technology TVs light up in a grid, each playing a different movie from the better part of the last century. Suddenly, Hawke’s face is superimposed onto a nondescript ’50s actress’s body. Suddenly, she’s watching a version of herself on TV, lipsticked and paranoid-looking, clutching her head before leaving the many screens blank. In the narrative for the music video for her single “Missing Out,” Hawke has audiences right where she wants them—forced to confront how seeing yourself can be migraine-inducing, all to the beat of a sparkly, acoustic guitar-heavy indie song.

The daughter of actors Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman, the 25-year-old actress and singer-songwriter is aware of the mythology her parents’ careers have created for her (in “Missing Out,” she sings that she was “born with her foot in the door”), but knowing that she’s got her “mind in the gutter” and her “guts on the floor” is also key to understanding who she is. Hawke’s third and forthcoming album Chaos Angel uses its 10 tracks to catalog the heaviness of heartbreak and regret (“Dark”) as well as the levity of feeling ready to “give up, be loved” (“Black Ice”). Her lyricism goes a step beyond honesty, showing a fearlessness that also comes across in her acting, as seen in her recurring role as Robin Buckley on Stranger Things or as scientist-ingenue June in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City. She stars as Flannery O’Connor in Wildcat, a film directed by her father and largely inspired by her obsession with the Southern Gothic writer, which is set for theatrical release this spring.

Kim Gordon is bummed she missed the early screening of Wildcat at Telluride Film Festival this past fall, where she and its star first met. Like Hawke, there are many mythologies that surround her: she’s an artist, a curator, a feminist icon, a mother, and a Girl in a Band, per the title of her 2015 memoir detailing her time as Sonic Youth’s bassist. Earlier this year, Gordon released a solo album titled The Collective. Remaining true to her conceptual art approach to making music, the sound artist opens the album with “BYE BYE,” a four-minute list of products you might find scrawled in the notebook of a modern woman who really doesn’t want to forget anything in her carry-on. Whereas her previous solo album No Home Record opened itself up to more resonant, shattering electric guitars, The Collective explores closedness, the crush of hi-hats and the whine of high-feedback string instruments—our collective erosion into commodities.

When reconnecting with Gordon over Zoom, Hawke lists her musical inspirations—Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and, she doesn’t hesitate to add, Kim Gordon.

Maya Hawke: I’m so happy to be talking to you, Kim.

Kim Gordon: Yeah, we met briefly at Telluride last September. That was an amazing five days. I’d never been before.

Maya: Me neither. What did you see that you liked?

Kim: I really loved Anatomy of a Fall and The Zone of Interest… Fallen Leaves, Poor Things. I was so riveted by Emma Stone and everyone else’s performances, I didn’t even think about it during the movie. Emma’s awakening through the mythology of what a woman’s supposed to be… Did you see El Conde?

Maya: No.

Kim: It was amazing, too. [Pablo Larraín] really screwed around with our ideas of Pinochet, making him a vampire, and also making Margaret Thatcher a vampire. [Laughs] That’s its own kind of mythology.

Maya: That’s amazing, I’ll have to watch it. With what you were saying about what it means to be a woman with Poor Things—I ended up getting into a lot of arguments about the movie with people. A lot of young women felt like the character was over-sexualized. I was so surprised because I thought she was just the kind of person who really liked sexuality.

Kim: There was so much innocence about her, so her awakening to sexuality was really something you couldn’t separate from her innocence. And we live in a culture that’s so not innocent. I talked to a friend of mine who lives in Northampton. (I lived in the Amherst-Northampton area for, like, way too long, 17 years.) She was talking about her teenage daughter, and how all the girls are obsessed with this ultra-femininity, and she doesn’t understand it. She’s like, ‘Wait a minute, are we going backwards or not?’ It’s strange to see that that can exist even in that leftist environment.

Maya: Totally. At the same time of all of this hypersexualization of young people, statistically the amount of young people who are going out, socializing, dating, and having sex is plummeting. So it’s this visually sexualized environment and practical isolation.

Kim: I don’t know if it’s because we’re also hyper aware of everything now or whether it’s a combination of awareness and watching too much reality TV. My daughter was a teenager when the Kardashians started up and the other reality shows like that with this extreme melodrama, and I kept thinking, ‘Is this teaching people how they think they’re supposed to act with each other?’

Maya: I feel like the jury is still out scientifically on whether or not violent video games make you more violent, or sexual TV shows make you more sexual.

Kim: They say ‘not,’ but I don’t know. Historically, it’s hard to say whether films reflect the times, or whether they idealize and create these myths about how we’re supposed to be in love, how we’re supposed to have sex—all these things that become so ingrained in our social DNA.

Maya: That applies to a question that I really wanted to ask you. I grew up around all of these stories of people like Sam Shephard and these artists in the DIY scene who didn’t want their songs in commercials, didn’t want to act in a cheesy movie, didn’t want to do press. Sam Shephard had a play open on Broadway and his friends apparently grabbed him after and were like, ‘You can’t go to the afterparty. That’ll suck you into a world of just trying to please the man. No one should celebrate you, you’re an artist.’

I was curious: Do you think that there is a decrease in outsider artists like that, or that the definition has shifted?

“When I’m making something, I feel no regard for whether or not anybody will like it.”

Kim: I do think there is a shift. You know, I moved to New York to do art and fell into playing music. And the music that we were inspired by was very noncommercial. I always thought of LA as that commercial place—like, that’s where the industry is. There are still people who are experimental, but that’s a whole other scene. You just want to get your music heard, and it’s so hard to get it out there now without doing the corporate thing.

I think it’s also all about context, and as you said, times have really changed. For myself, I think it’s a challenge. I’m still making weird music. But I think that people are also more used to hearing dissonant music, and they’ve been listening to that now for many years. It’s nice to expose people to all kinds of music. I do still feel super anti-corporate.

Maya: Does that have anything to do with why you paint?

Kim: No, because the art world is horrible. [Laughs] It’s just as cor- porate as anything else. I’m more drawn to conceptual art, and I paint, but I try to incorporate it into some added context that makes it a little more interesting. That’s why I make the kind of lyrics I make. From a very early age, I’ve been drawn to things that are unconventional. It’s not like I’m trying to be unconventional, that’s just who I am. Everyone’s different. Some people have huge ambition, and some people are just driven in a different way, or have a different idea of success.

Maya: And you feel like that’s still just as true now as it ever was?

Kim: I think so. Like you’re saying, I think it is true that bands [today] don’t have the same consideration as they used to. They’re just trying to make it. But, there’s always a small percentage of bands coming out of the world that I came into. [Bands who] were devoted to the music more than making a song that everyone’s going to like.

Maya: When I’m making something, I feel no regard for whether or not anybody will like it, and it’s even better if it feels like people wouldn’t like it or that it wasn’t mainstream. But then I get so mad at myself because I go to put something out and I really want people to like it.

Kim: I feel the same. When I’m making something, I honestly don’t think about who the audience is, but I am also thin-skinned. I have a huge desire to please, but when I’m actually making something I have a ‘fuck it’ attitude.

I think that’s normal. You just want more people to hear what you make.

Maya: That’s usually the guide to which I try to judge a success or a failure. It’s like, ‘Well, am I allowed to do it again?’ My album was a success if I’m allowed to make another album.

Kim: You also do movies. How do you feel acting-wise compared to making music? Do you have the same attitude when you’re acting?

Maya: Acting is a little different. There’s something about it that’s almost more like being a session musician. You try to be practiced, have your instrument tuned. You’re trying to play someone else’s song. That’s a very creative act, you can make up your own solo and maybe they’ll incorporate that in, but you’re still participating in someone else’s dream. There’s something about that, for me at least, that’s extremely relaxing. I can take my ego and put it away and feel a part of something bigger.

I know you wrote a book called Girl in a Band. I play in a band of all men, and I know that you did as well in a different time. I’m curious as to why that title? And what was it like?

Kim: I honestly chose that title because every female musician at some point was asked ‘What’s it like to be a girl in a band?’ and I never really thought about it until people started asking me that question.

I think girls talk about more things to one another. [Laughs] Men, you know, it’s just like parallel play or something. Now I accidentally play in an all-girl band, but it wasn’t by design.

Maya: I feel like men have changed a lot. Young men these days, I feel they almost talk about their feelings more than women do. This idea of parallel play… I feel like I fell into a situation where I was in a band of extremely great musicians when I was at the beginning of learning about making music, and very far away from being willing to take on that title for myself. I saw myself as a poet in a band.

Kim: I mean, honestly, I never considered myself a musician, and I still kind of don’t. I’m more of a visual artist who makes music. Sarah, the guitar player in my band, is like me, she came up in the downtown music scene in New York. She had a band called Talk Normal, this duo that I really liked. It’s weird, they’re much younger than me, and their music experience is way different, but we somehow all get along.

Maya: A lot of my heroes—you, Joni Mitchell—refer to yourselves that way and are more known as musicians. People always ask me, ‘What’s more fun, what’s more your thing?’ about painting, acting, and music. But the desire all feels like it comes from the same place, the desire to make a painting and the desire to write a song. Initially, doing music for me was to have one of the arts in my life that I make not be corporatized. I was like, ‘Okay, I’ll be a professional actor, and I’ll do music for fun.’ And then I started doing music professionally, and it’s like, ‘Okay. I’ll paint for fun.’ So they feel one and the same. I’m wondering if that’s true for you too?

Kim: I tried to keep them separate for a long time. I realize they’re all different outlets, but the feeling is one and the same. I still think in terms of images—spatially and visually. In terms of lyric writing, I feel like I see words and a chain of images in my head. When I’m doing a vocal, it’s maybe a little bit like taking on a character or acting.

Maya: There’s this journalist named Jonathan Cott who was a long-time writer for Rolling Stone back in the day. He was talking to me about five years ago about how he thought of [Bob] Dylan’s songs as memory palaces. How they work is you can imagine a deck of cards and attach memories to the images on each card to remember more. He thought that Dylan lyrics were so visual that you could hide memories inside the imagery he creates.

Kim: I grew up as a teenager listening obsessively to Dylan’s records. But I’m normally not a lyric person. When I hear music, it’s not always the first thing I listen for. But I remember so many Dylan lyrics. Maybe it was just the time in my life.

Maya: Your lyrics are so vivid and visual, it’s surprising to me that you don’t normally listen for them.

Kim: Some people will hear the lyrics and that’s the first thing they pick up on. I only do that if I really like something. I remember when I first heard that Cardi B song ‘Bodak Yellow,’ and that song has the greatest lyrics. This one line is like ‘I don’t dance now, I make money moves.’

Maya: I never thought about that line particularly. It’s metaphorically very beautiful.

Kim: It just sticks in my head. And then referencing her Louboutins like bloody feet.

Maya: Both of those things are so visual and metaphoric. Sometimes when songs start to list different brands and purchasable items my brain just turns off. But I think I could be missing some really cool poetry by doing that.

Maya Kotomori: In a way that’s a new mythology in music, where those products are less about flexing, but personification. These brands become characters. I see that idea in both of your initial music video releases. Kim, in “BYE BYE,” where you sing what sounds like a packing list, and Maya, in “Missing Out,” where you watch yourself superimposed into old movies on a wall of screens. The character is what a person could own or what they could represent, but never themselves.

Kim: I was just thinking about this: What’s the difference between a myth of somebody and a myth of somebody’s brand?

Maya: I think personal brands say a lot about personal myth, and trying to create a story about you that elevates the work you make. That’s what brands do, and I guess that’s what some artists do. ‘If you listen to my music, you’ll be tough, or you’ll be cool, or you’ll be sensitive.’ So you end up minimizing into a brand image that you can advertise on this social media plat- form that everyone needs you to have.

Kim: That’s well put. I think that takes away from being able to keep growing as a person or in what you put out [artistically] because you’re so busy having to maintain this thing.

Maya: There is so much mythology to your career and to your band and to your art. Is it ever scary to make something new or different from inside that history and that world that you’ve created?

Kim: Not really; I don’t know. I just feel like, what do I have to lose? I just get bored. I’m still really doing what I’ve always done to a large extent.

Maya: It seems that way to me. [Laughs]

Hair Peter Butler at Tracey Mattingly. Make Up Mary Wiles at Walter Schupfer Management. Set Design Alice Martinelli at CLM. Digital Tech Alexandra Kuhn. Photo Assistants Daren Thomas, Ricky Jackson. Stylist Assistants Isabella Damazio, Lucia Fiore, DeVante. Set Design Assistant Aaron Bledsoe. Production Gwendolyn Anderson. Production Assistant Nifemi Adegboye. Casting Tom Macklin.