For Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue, the artist and trans starlet’s divahood is reconsidered five decades after her passing

New York is full of divas. But despite their popularity, divas don’t always get their critical due. Some legends’ reputations overshadow their own talent. Candy Darling has come to symbolize the fickle nature of stardom as a trans woman who came before her time, but she wasn’t just another young, tragic thing. She was a superstar. “My business is not acting,” she once said. “My business is the Candy Darling business. This I built myself.” A new biography from Cynthia Carr, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar, outlines her enterprise with juicy detail and stunning prose.

We learn, among other things, how she never really smiled. In photographs she was always on the precipice of joy, never fully committing to a grin. Everyone commented on her sadness, from the cruel words of Fran Lebowitz in the 2010 documentary Beautiful Darling to the listless pandering of Andy Warhol. But in spite of the endless disappointments she faced during her lifetime, Candy was not merely a victim—she was a career woman. And what trans woman isn’t?

Candy took advantage of every opportunity that came her way: plays, avant-garde movies, turning tricks, dating famous directors, and meeting budding starlets downtown. For years, New York was her own private playground. But soon baby got tired of her playpen. She wanted to be a Hollywood queen, like her beloved screen idol Kim Novak, but she could never quite escape the vicious judgment of the times. “What could be more with it than a sex change? And only five blocks from Bloomingdale’s,” one reviewer cynically wrote of her early attempts at stage acting that took place close to the department store. Fortunately, Carr’s new biography depicts both the era and Candy’s attempts to break the mold in equal measure—refusing to cast her as a hero or lost cause. It-girls aren’t vapid self-creations, they’re also some of the most resourceful creatives around. When the going got tough, Candy would fashion clothing out of whatever beautiful scraps of fabric she could find.

The problem was that Candy was the worst thing one could be in the ’70s: sincere. While trans icons now drape themselves in irony, Candy was as real as it got. She’d coo in her gentle falsetto and bat her long eyelashes. Jackie Collins said that Candy “has more femininity in her than most females will ever wish to have.” (It almost sounds like a threat. Sincerity was prickly.) Andy Warhol considered the term “superstar” ironic, but Candy wanted to be a big MGM Studios starlet, not queen of the gays. Toward the end of her life, she did a lounge act at the disco nightclub Le Jardin, apparently struggling to hold a pitch. It was not the career relaunch she so desperately desired. “Faggots are the most superficial thing on the face of the earth,” she complained in her diary afterward. Nowadays, the gays would eat this up, but back then she may have alienated the few people who had a stake in her career. Candy wasn’t in it for laughs. Sometimes she would say she was interested “in the product of being a woman,” but this was almost always followed by declarations like: “How dare you call me a transvestite. I’m a woman and I’ve got the tits to prove it.”

Candy desperately wanted to be “normal” and referred to her penis as her “flaw,” though she ultimately didn’t end up getting surgery. It’s easy to start here and write the ballad of unrealized trans talent: She came up in the grimy downtown theater scene alongside Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn then got discovered by Warhol and placed in bit parts until he got bored of her, never getting the starring role she dreamed of. Carr’s biography doesn’t shy away from the grim side of her life (the very hormones she took made her sick). Instead, she slyly contextualizes Candy’s political landscape. Surprise: Candy didn’t exactly have class consciousness. She didn’t care about STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), Stonewall, or the gay bars that barred her from entering. Other trans women were often her competition, and she made few steady friendships until close to the end of her life. Nothing is glamorous from all sides.

Many of Candy’s best lines were ad-libbed. She prattled about the pitfalls of Hollywood or did Kim Novak impressions, sometimes derailing plays by doing lines from her favorite film, Picnic. After her difficult childhood, fantasy became key to her survival—and as she ascended the strata of the Downtown scene, she would lie about details from unrealized films, having country houses with servants, and even needing a Tampax. After appearing in Jackie Curtis’s play Glamour, Glory, and Gold in 1967, Candy and Warhol became fast friends. “For the first time I wasn’t bored,” the God of Pop Art declared. One reviewer noted Candy’s performance: “Hers was the first female impersonation of a female impersonator I have ever seen.”

Candy appeared in Give My Regards to Off-Off Broadway shortly after, a satire that made fun of the bad coffee at experimental theaters like La MaMa. Valerie Solanas even asked her to star in her 1965 feminist play Up Your Ass, though that ended up falling through. Instead, Warhol Factory director Paul Morrissey decided it was time for Candy and Jackie to appear in a film and orchestrated a small scene in Flesh where they bitched about indecency. The Warhol gang seemed to find it ironic that trans women cared about propriety, but while Candy did sex work, she refused to watch orgies or change in front of others. She was a nice, proper girl.

After Solanas shot Warhol in 1968 for refusing to make her a superstar, he decided to never give anyone anything they asked for. This suited Candy, who—ever the coquette—rarely asked him for anything. What’s more womanly than that? She rode his coattails silently in the hopes of getting a big part. Years later, when Candy was dying from cancer brought on by the cheap hormones she’d managed to score, Warhol gave her a black-and-white TV as a gift. Like any good diva, she asked for a color set. He delivered. (Perhaps the guilt of never visiting the hospital was getting to him.) She passed away from lymphoma in 1974 at the age of 29.

After a long delay, Warhol and Morrissey produced Candy’s biggest film, Women in Revolt, in 1971. Not everyone knew what to make of it; feminists abhorred it and many filmgoers seemed to ignore it entirely. The film stars Candy as a woman named Candy who’s in an incestuous relationship with her brother. A feminist group called P.I.G. wants her to join their cause in order to bring some glamor to their crusade. Candy’s character instead tries to find liberation through Hollywood, only to face constant sexual harassment. In an autobiographical twist, the film seems to mock the very dream Candy harbored for so long. After she makes it big, a reporter attempts gotcha journalism and asks her about her past incestuous relationship, her involvement with P.I.G., and her lack of talent. He calls her a B-movie wannabe, and the two end up having a vicious physical fight on camera. Candy helped write this scene, a curiously meta take on her difficulties making it in show business. Her diary reveals similar ideas for film scripts, gags, and lounge acts.

Rumor soon arrived that Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge, a bizarre novel about a trans woman who (sort of) detransitions, was going to be adapted to film. Candy decided it was the role she was meant to play, hoping to break into Hollywood. While behind-the-scenes important men tried to get her an audition, the role ultimately went to Raquel Welch. It’s now considered one of the worst movies of all time. After failing to get the part, Warhol said Candy was bitter. She had met the trans glass ceiling. She could get bit parts alongside Sophia Loren in Lady Liberty or Jane Fonda in Klute, star in plays like Vain Glory, or play a drag queen in Some of My Best Friends—but she could not get a real, meaty role.

“We must consider Darling’s legacy—as a starlet of melodrama, a conservative fashion princess, and a romantic dreamer—as a singular artistry of her own design.”

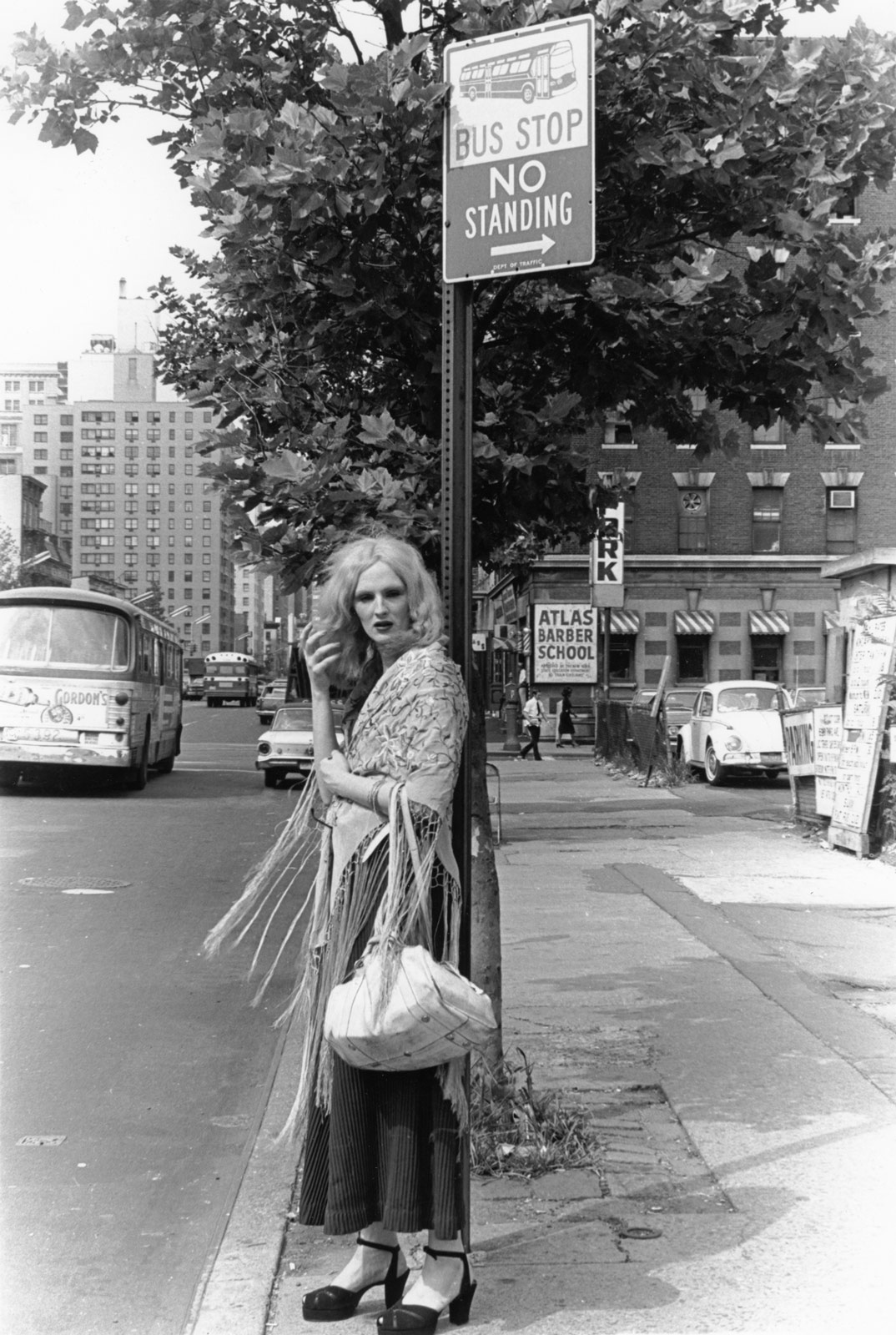

Meanwhile, Candy became the face to launch 1,000 songs. She was always pale as snow, with lipstick a stark red or pink—one shade behind the times. She kept her short blonde hair blown out around her like a halo. She was beautiful, wearing glamorous gowns and scarves that resembled a lion’s mane while hiding the teeth that so embarrassed her. She even learned her angles precisely enough to pose like royalty on her deathbed for Peter Hujar. No one has been able to replicate what she did, but many have tried to describe her allure.

The Rolling Stones wanted her and her friend Taffy to come see them in the song “Citadel,” perhaps a nod to Warhol’s notorious Factory. Some suggested that The Kinks’ “Lola” was about Candy, but it may have been another example of rock music turning toward trans women as a sign of the times, something to shock the radio into modernity. Women being men were all the rage—Lou Reed penned his classic “Walk on the Wild Side” about Candy allegedly giving head without losing hers. (Reed went on to date a trans woman named Rachel Humphreys before tossing her aside, an all-too-common trend of the time.) He also wrote “Candy Says,” the sad tranny ballad of the century: “Candy says, ‘I’ve come to hate my body / and all that it requires.’” Yes, she had. And men never made it any easier.

Candy briefly dated Jane Fonda’s director ex-husband Roger Vadim. He even gave the Warhol superstar a silver ring. Of course, her “flaw” came up; they only slept together once, or at least that’s what she told her friend Jeremiah Newton. “It hurt,” she said simply. Her journals were more revealing. “Never feeling I was really a woman, I never felt worthy of a man.” And later, nearing death: “Desperately desire lover. Want to please man. Despise my body. Will appeal to God to help me.” The classic challenge for the heterosexual trans women today remains the difficulty in establishing harmonious matrimony. And, of course, having children. Once while walking with Jeremiah in Manhattan, a woman shooed Candy away from her children. Jeremiah was shaken. “You don’t understand,” she said. “This happens to me all the time.”

In 1972, Diana Vreeland put Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn, and Jackie Curtis in Vogue. The three hover like talking heads, though Candy has a small lollipop she awkwardly holds like a magic wand. It says “LOVE ME.” It was a rare win for three girls whose notoriety often outpaced their actual starlit autonomy. (The artist Greer Lankton would later make dolls of Vreeland and Candy, the latter for the 1995 Whitney Biennial. Many of Lankton’s dolls also had little hearts inside that said “LOVE ME.”)

Two months after Small Craft Warnings opened off-Broadway in April of the same year, Candy took over the role of Violet, a trampy cis woman who flirts with a married man in a small coastal bar. It was one of Tennessee Williams’s many comebacks, and this time he spent some time acting alongside Candy as the male lead. He loved her, though he was often drunk. A video interview from the time suggests she found his inebriation uncomfortable. Still, for Candy it was a dream come true. She was the elegant young thing—even though the women in the cast forced her to use a closet as a dressing room. She fixed a star to the broom closet, always the author of her own stardom.

How do you let a dead trans woman speak for herself? We’ve been asking this question for far too long without any satisfactory answers. It’s easy to dismiss yesterday’s trans starlets as victims, brought down too soon by the times. It’s much harder to see through the mess and admire the work they did achieve, as artists or as icons of trans representation. We have a tendency to cannibalize their stories as our own, to pose them like dolls for our pet theories on divahood. But we must consider Darling’s legacy—as a starlet of melodrama, a conservative fashion princess, and a romantic dreamer—as a singular artistry of her own design. Besides, that diva probably wouldn’t have wanted to talk to most of us anyway.