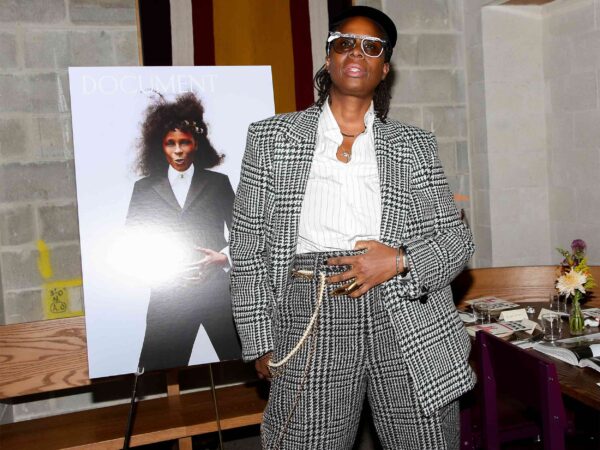

The choreographer and conceptualist challenge the categories and moralities of the artist for Document’s Spring/Summer 2024

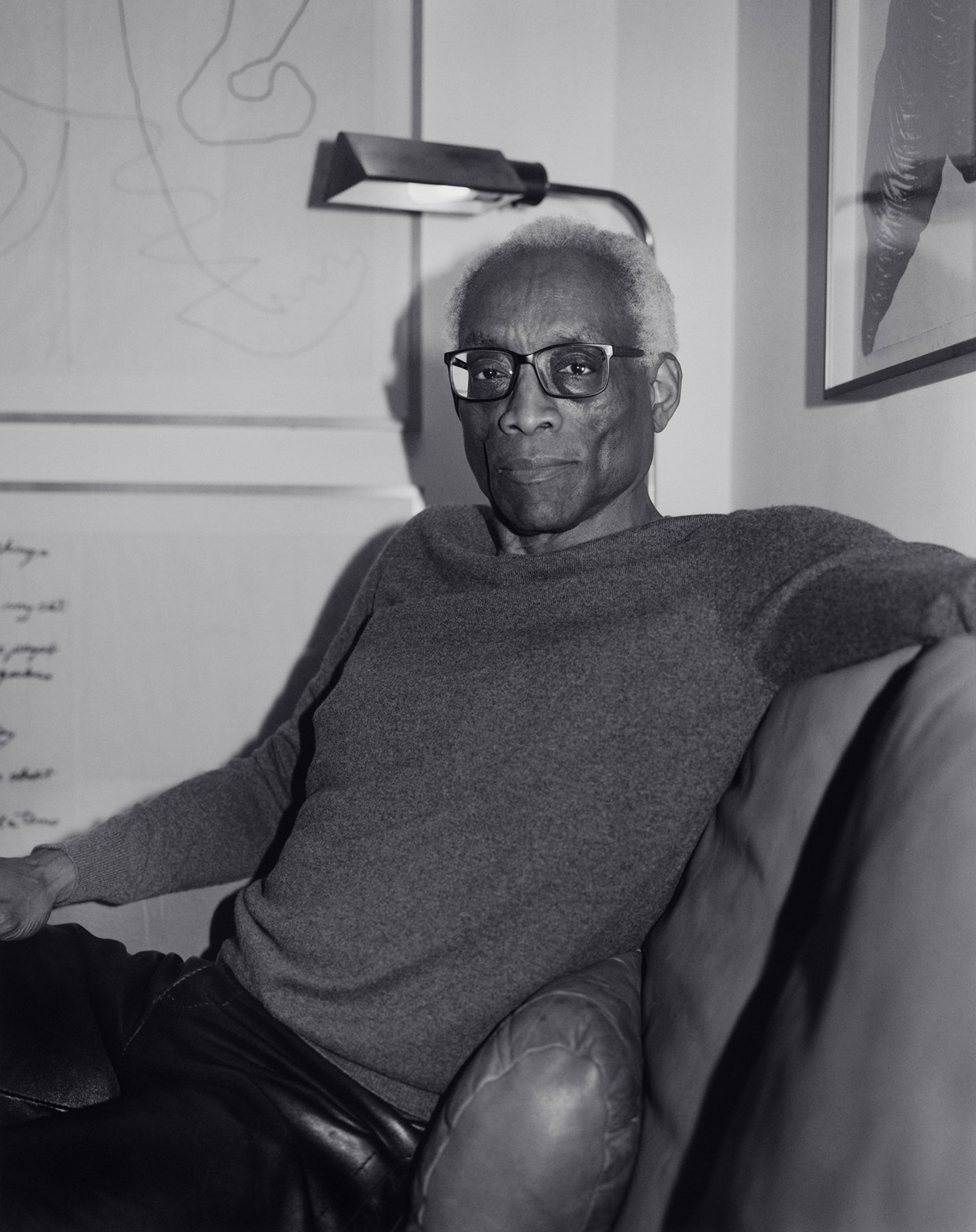

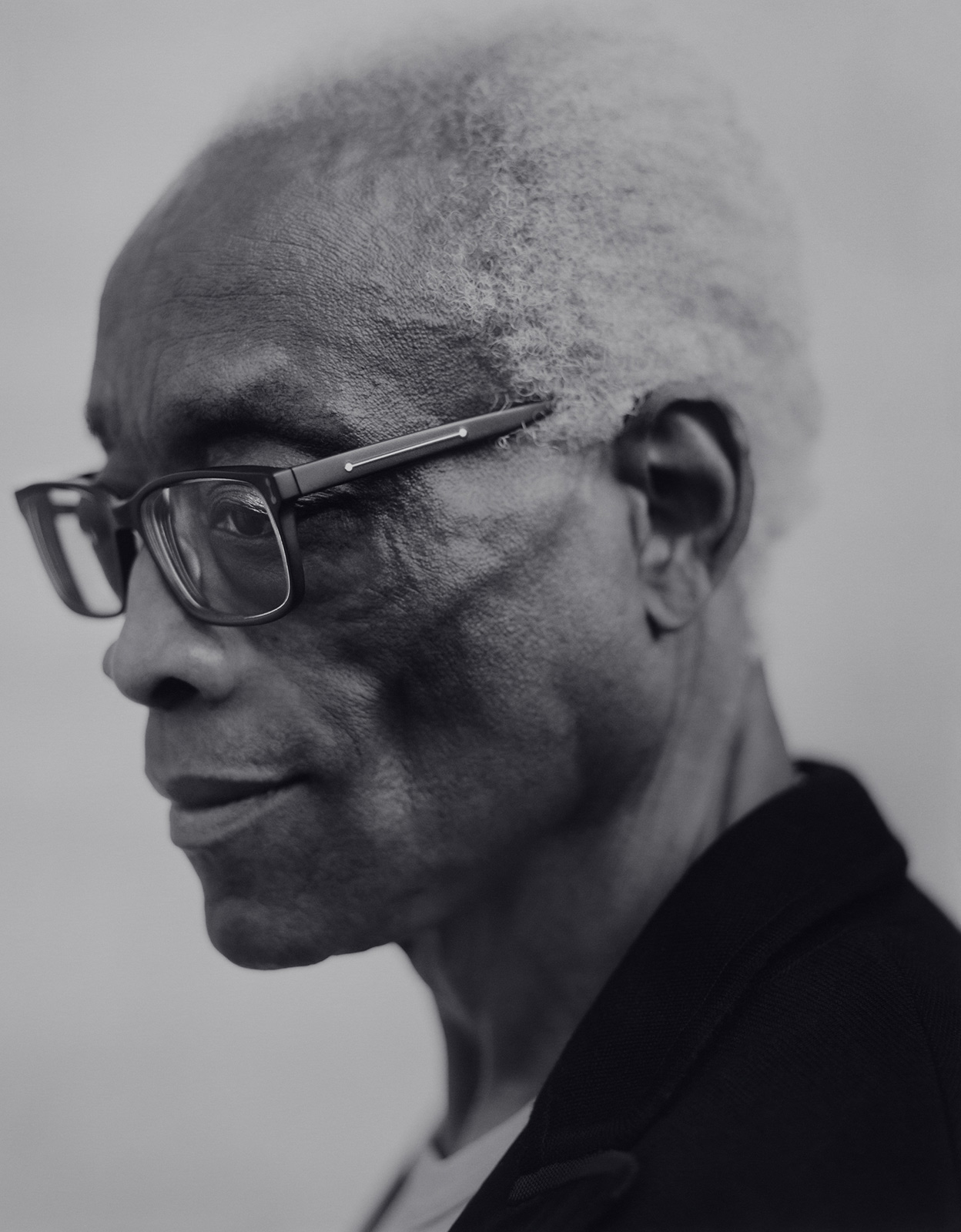

“The body never lies,” wrote Martha Graham in her 1991 autobiography Blood Memory. The mother of modern dance famously theorized in absolutes, with superlatives aplenty, when describing her novel approach to movement. “Martha Graham was known for her more categorical statements,” says Bill T. Jones, renowned dancer and choreographer, with a knowing look. In his smooth baritone, he lists a series of his own categorical statements, some of which he holds sacred. Others “might make people think, ‘Oh my god, that sounds like bullshit. It sounds like what he believes is mythical.’”

“We can poke holes in them later,” Jones assures.

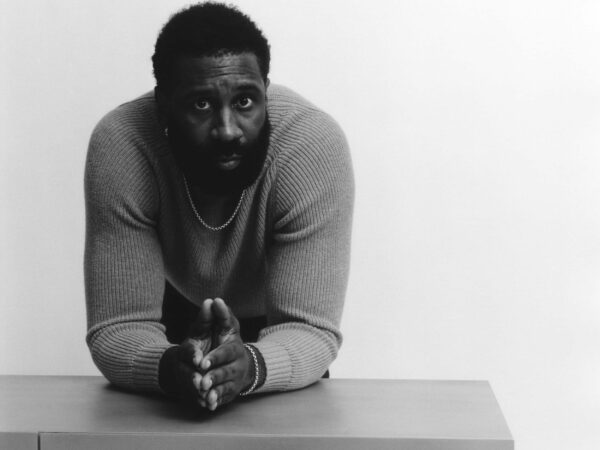

Conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas smirks at the prospect. For him, one prevalent myth worthy of deflation is the idea of the artist as arbiter of good or bad taste, of right or wrong political views, of morality as such. Thomas and Jones’s practices don’t just oppose this kind of obligation, they obliterate it, using a radical sense of self as a compass.

Jones’s hybrid spoken word choreography engages audiences in active aural and physical meaning-making, while Thomas’s practice across a range of mediums, materials, and scales holds a magnifying glass up to contemporary culture. In Jones’s seminal 1995 performance Still/Here, an ensemble of people suffering from illnesses translated their feelings into expressive movements which bled into an interpretive dance about the choreographer’s own life story. The disjunction of form and content articulated by a soutenu following a spoken-word passage about someone dying from cancer, as with Thomas’s prints made from prison uniforms to spell phrases like “land of the free” and “we the people,” remind viewers of the tenderness that lies beneath the aesthetic. Black identity emerges in both artists’ work not as a calling card, but as a visual language of history and love.

For Jones, the body is the meaning is the message. His love of dance comes from equal parts circumstance and access: In 1955, his parents relocated him and his 11 siblings from Bunnell, Florida, to New York’s Steuben County for greater opportunities harvesting crops. An all-star track athlete in his teens, Jones would attend Binghamton University on scholarship in 1970. After falling in love with West African and Afro-Caribbean dance via classes taught at his college, he switched his major and met Arnie Zane, his partner in life and dance, who died of HIV/AIDS in 1988. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, Jones produced numerous works both independently and in collaboration with Zane as the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, which served as a home for like-minded, experimental dancers.

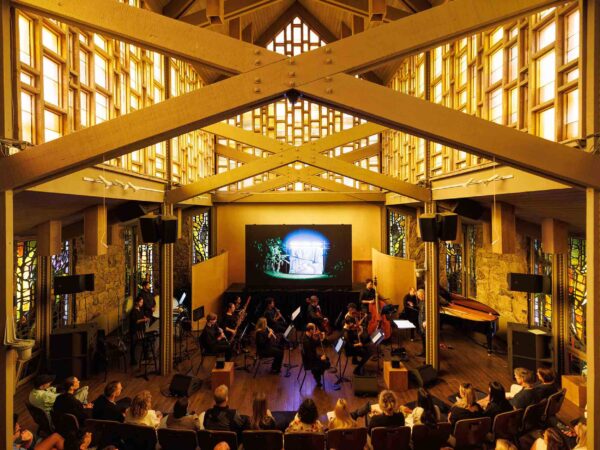

Today, Jones is the artistic director of New York Live Arts—an aggregation of his former dance company and Manhattan’s Dance Theater Workshop—and will be celebrating 40 years of the landmark venue Harlem Stage with his company in a two-night-only event this spring. He still lives in the house he and Zanes bought in Rockland County, New York, in 1979.

Born in Plainfield, New Jersey, in 1976, Hank Willis Thomas is the child of jazz musician Hank Thomas and photographer, artist, curator, and educator Deborah Willis. After cutting his teeth as an undergraduate at New York University and as a graduate student at California College of the Arts, Thomas synthesized his degrees in photography, Africana studies, and visual criticism into the carefully considered multimedia art he creates today. In addition to showing at institutions like the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim, in 2022, Thomas unveiled his largest work to date: The Embrace, a 20-foot-tall bronze sculpture in Boston Common inspired by how tightly Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King held each other when the late civil rights leader won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Both use their work as a challenge, employing the body alone and together, on stage, in the gallery, and on the street. Speaking together for Document, Jones and Thomas find meaning under myth—and tease apart the categorical declarations that underscore the persona of the artist.

“I’m going to ask, because I have made art the center of my life, am I fierce enough to play at that level? Or am I always trying to be good?”

Bill T. Jones: Art flies above societal questions of power, class, etc. Art has a sacred function. Martha Graham is known to have said, ‘Dancers are acrobats of god.’ Art should be free of capitalist principles. Art should be free of all hierarchies of value. That’s my throw-down.

Hank Willis Thomas: One [myth] that I gained through you comes from James Baldwin: ‘It seems to me that the artist’s struggle for his integrity must be considered as a metaphor for the struggle, which is universal and daily, of all human beings on the face of this globe to get to become human beings.’

Bill: That sounds like Baldwin.

Hank: I believe that there is no culture without art, and that culture is what humanity is founded on. So art and humanity are indivisible. History doesn’t repeat itself, it just continues and takes different forms. In other societies where we might have a shaman or a seer or a healer, here we have artists. Those are my efforts to reimagine the definition of history and artist so that it’s connected to the continuum of the human spirit.

Bill: Well, I don’t know what I expected, but that’s kind of breathtaking, that list of things. Of course, I want to start quibbling about terms. What do you mean by culture?

Hank: Art and humanity are indivisible—built into that is the idea that there’s no art without culture. Most of what we know about ancient Egyptian or Aztec or Mayan societies is through their cave drawings, through their art.

Bill: So that’s not a myth. In your way of thinking it is an axiomatic truth that art and humanity are inseparable. I will say, I’m not sure what humanity is. And I’m not even sure that there is a ‘we.’

Hank: Yeah, I don’t believe there’s a ‘we.’ I also relate to the individual framework. There is a book called Finite and Infinite Games written by a theologian named James P. Carse that was really life-altering for me. He says, in this book, there are two types of games. There are finite games that come to an end when there is a winner and a loser. But the goal of an infinite game is to remain in a state of play. And therefore, the rules always have to change. When I look at our society, I think about some of the people who are most reviled. They often are infinite game players, because they wind up breaking the rules so that they can keep playing. Those of us who are so accustomed to the rules are like, What’s happening? I think about our last president being one of those people who has broken all the rules so he can stay in the state of play, and the people who have played by the rules feeling cheated.

Bill: I’ve been thinking lately about the phenomenon of Elon Musk. Elon Musk will play a huge role in the future. Right now, he is for some of us, very disturbing. I want to use words like reviled as well… Is this a new myth, or an old myth: Art is free of morality.

Hank: Can you say more on that?

Bill: It doesn’t matter if you are a sumbitch, as long as you make something that people want. Or even to go further than that, as long as you make something that moves the needle of humanity forward. The chips in the brain, Elon Musk’s technology, promise some amazing things—I’m hearing today about paraplegics who are now able to use their computers because of this technology. To understand what a game changer that is, I have to get my morality out of the way. And therefore I’m going to ask, because I have made art the center of my life, am I fierce enough to play at that level? Or am I always trying to be good?

Hank: This reminds me of this South African artist, Nicholas Hlobo. He said we have to live in the ‘tomorrow’ because that way you won’t be surprised when you get there. He said that the problem with South Africa post-apartheid was that people weren’t living in the freedom they wanted. So when it came, they didn’t know what to do with it. Someone asked him, ‘Do you feel a responsibility as a Black artist to represent?’ And he was like, ‘It’s up to me whether I want to be a comrade or sellout. I may not want to sing your song.’ It is up to me whether or not I want to be a comrade or a sellout.

Bill: When he throws in ‘sellout’ he loses me. Is it possible to be a politician in the world of art, being able to get paid, and still be a valid artist? I think so. It’s difficult work, but it’s possible. If I’m getting him right—he sounds like a remarkable man—it sounds like he believes that there is a kind of right and wrong about it. My point was, when you talk about art, artists should be free of any concerns about being right.

Hank: I connect that with what he’s saying. I think his interpretation of a sellout was from the person asking, ‘Don’t you feel this responsibility?’ And if you don’t, you’re a sellout. There are people who are just like, ‘I want to get paid and that’s all I care about.’ The morality of whatever else doesn’t matter. As we saw with artists like Bert Williams and Stepin Fetchit, and even to a different degree Hattie McDaniel—these people are Black artists who performed roles that many people saw as degrading, but also opened the door for so many other people. I think it’s up to the art-maker. That’s where I come back to.

Bill: Well this is a question I have for the editors giving us this expression [‘New Mythologies’]. Whose new myths are we talking about? Artists individually, or accepted myths in culture?

Maya Kotomori: That is the question, isn’t it? Both are myths, however some are more widely accepted, more hegemonic, than others that only affect the individual. So with this conversation about who is able to break the rules, I’m thinking about these states of play you mention, Hank. And a shifting mythology of what responsibility is. Responsibility, I think, is this overarching sense of mythology here. So how has the idea of what is responsible in let’s say, the mid-’90s—I’m thinking of your work Still/Here, Bill, and the response from white people specifically.

Bill: Most of the writers [responding] were white people. But you know, I never even heard Black people weigh in on it. Still/Here was decried as a work of ‘victim art.’ It was decried as a work wherein I was playing on the emotions of a willing public. As the person from The New Yorker whose name shall not be mentioned said, ‘Don’t go see this work, because he wants you to feel bad. And that’s what these people do. They make this kind of work to make you feel bad. Don’t go.’ I’m glad you bring that up, because I’m trying to get us to make categorical statements as new myths.

So ‘should.’ What should artists do, or what should artists be? One thing we saw during the George Floyd era: Everybody was concerned about appropriation. You should not use the forms of people who are from another fill-in-the-blank—race, gender—than yours. I think that is wrong. I think artists should be free to do whatever they want to do. What do you feel, Hank?

Hank: I believe in the idea that ‘should’ matters on a cosmic level as a myth.

Bill: How do you mean ‘should’ matters on a cosmic level?

Hank: I’ve been thinking a lot about space and time, and why we are here. And if we detach ourselves from the logical realm, does ‘should’ matter? When you’re on stage, it doesn’t appear that you’re ‘should’-ing. It appears that you’re being. When I say cosmic, it’s just the only word I can use to define the wavelength that your audience is tapped into. We’re not moving, but we feel moved. With other performers, there is a ‘should.’ When Beyoncé is performing, if she does something that she shouldn’t do, it is clear, because everything is meant to be so deliberate.

“When I go into a performance—and lord knows I have a huge ego—saying, ‘I’m gonna do something important,’ the gods will slap your ass, you know.”

Bill: Let’s talk about the lady. I have great respect for her. There was a concert some years back where her husband showed up, and she, the feminist icon, sat down in a chair and let him come forward. At least the way I read it, I thought that she was signaling something about a corrective to the dilemma of Black men and Black women. Even though they’re both powerful, at that moment, she gave way to him and sat down. In my mind, I’m like, Oh, she shouldn’t have done that. And I have no right to say that. If that’s what you mean about when she does something she shouldn’t do…

Hank: In that way, I think she set a standard of expectation that creates a lot of ‘shoulds.’ She, of course, finds freedom within it. She’ll do a country album because she ‘shouldn’t.’ If you think about Jay-Z, and even Beyoncé, these are young people who were not given much in life other than the love of their communities. And they created mythologies about who they were in pop, in hip hop. They gave themselves new names, they made sound and dance and fashion together. And the hype of ‘who I am,’ and the musical boasting that we know connects to Caribbean and African traditions, becomes a global mythology. So now, this person who was from the Marcy Projects named Shawn is Jay-Z.

Bill: Now she’s more—here’s an evil word—middle class, isn’t she? I want to go back to something at the base of your very wonderful portrait of them. There’s something about [the idea that] to have the goods to communicate, particularly in a soulful way, you’ve got to have paid your dues.

I remember an interview that Miles [Davis] did with somebody who implied that you can only play the blues if you have suffered. And Miles said, ‘Hold up, man, my dad was a dentist. I went to Juilliard. I still play the blues.’ In other words, he was trying to puncture a myth that for Black people to be authentic, they’ve got to have tasted firsthand the trauma of race in America. That’s a myth, I think: ‘You got to pay your dues and you got to suffer to really represent suffering.’

Hank: I agree. What do you think about this line from 1984 by George Orwell, where he said, ‘Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past’?

Bill: I think that is so good. We should send that to Ron DeSantis.

Hank: This is also a part of the thing with cosmic mythology. Do we as artists sometimes not know that we are predicting the future? Even when you think about Dick Tracy and the [phone] watch, until someone imagines it and makes it seem possible, no one can actually make it happen.

Bill: This is interesting, that we’re sort of shuffling between the public and the personal, which I guess, two artists ‘should’ do. [Laughs] My parents were potato pickers, I’m a migrant child. Some people would say, ‘And you did what when you went to the university? You studied modern dance? Your people have been working to get out of the potato fields. You got to get a job where you can put down some serious dollars!’ And the thing was, because of education I thought, Well, what I do transcends those concerns. I am making something that is spiritual [and] has a validity that is not about paying the light bill.

I’m the classic story of the trauma narratives and Black society, but I don’t really accept that. When I go into a performance—and lord knows I have a huge ego—saying, ‘I’m gonna do something important,’ the gods will slap your ass, you know. You don’t say, ‘I’m gonna do something important.’ You do it. And you trust that the powers that be—and as we know, you’re a very successful artist right now, and it has to do with what the critics write, what the collectors do, all sorts of things—to determine if you’re going to be the one that doesn’t get forgotten, because artists come a dime a dozen. And some of them are pretty fierce. So how can I assume that what I do, no matter how wild it is, is important?

Hank: This is why I believe that the ‘should’ doesn’t matter.

Bill: Yeah. These words like ‘should,’ they get us in trouble, don’t they? But mythologies are based on ‘should’ and ‘must.’ ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’—but we must bend it. Right?

Hank: Alice Walker said something like, ‘Unless we change ourselves, we cannot be changed.’

Bill: Well, you believe that, huh?

Hank: Yes.