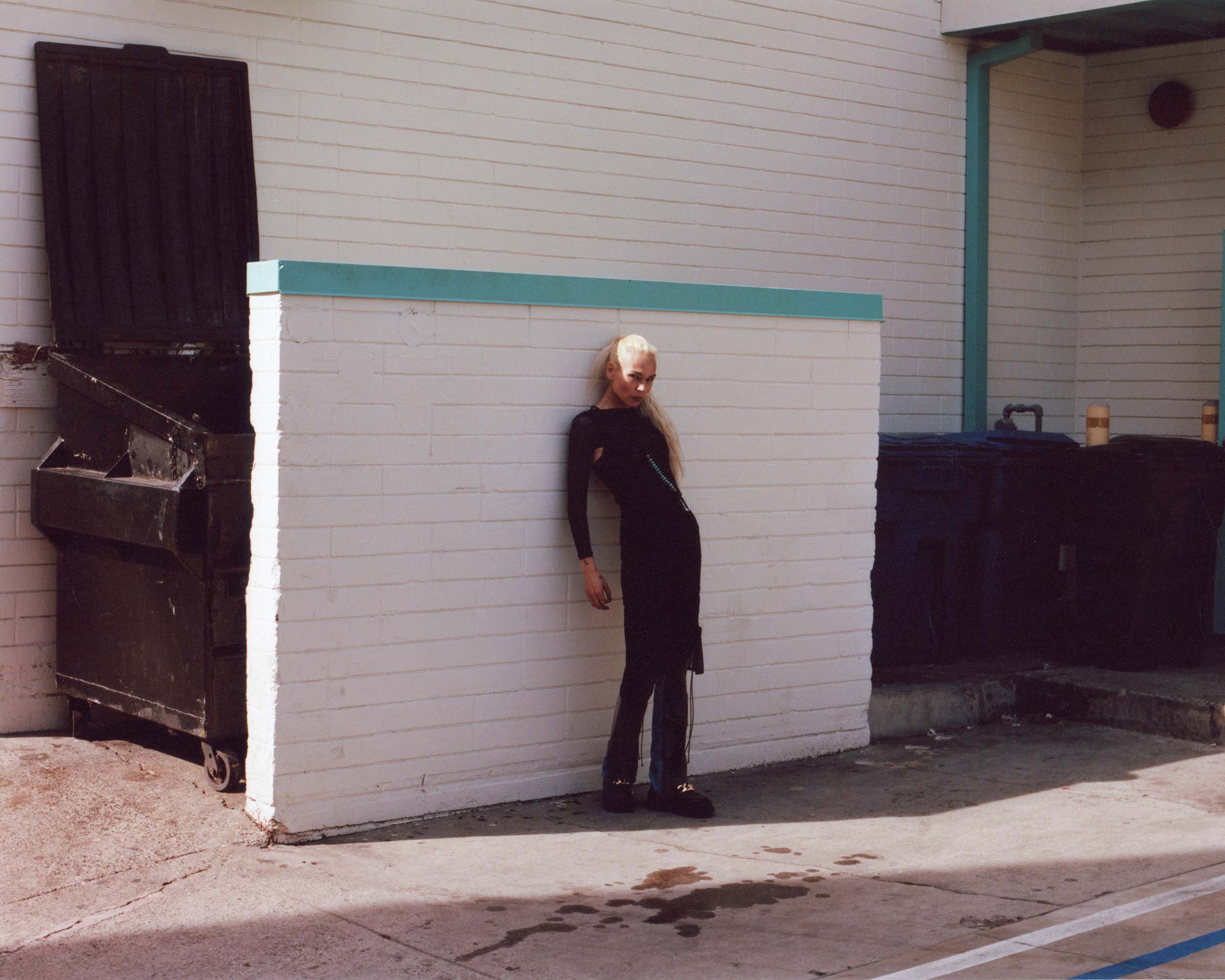

Ahead of her live performance at Barcelona’s upcoming Sònar Festival, the Swiss-Nepali artist talks metaphysics, trance states, and her latest album ‘Death Is Home’

Electronic musician Aïsha Devi is a metaphysicist in addition to being one of the most in-demand underground artists. “I developed my own techniques combining alchemy, proto-religious practices, and ancestral knowledge as metaphysical data that I inject into my tracks,” Devi tells me in a tone simultaneously friendly and exact. The Swiss-Nepali artist does this to “expand the brain, alter the perception of reality, and access a limitless state of existence.” Onstage, she embodies her given surname, which means “goddess” in Sanskrit. “It’s not about power,” she says. “It’s about giving something back to people. Becoming the goddess is the realization that you are the egoless self creator.”

I’m somewhat thankful to be communicating via a computer, with the internet as a buffer between our energies—according to her (and modern developments in quantum physics), “99 percent of existence is invisible, energetic, and electrical. Some still only believe in what they see,” she says. Our eye contact—sustained on Zoom—can only confirm that one percent of what I see is real. Looking at Devi, her spiritually ego-less definition of “goddess” by her definition is the best way to describe the other 99 percent that I can’t see with my own two eyes. This is what her music is concerned with. “Zero and one can only be zero and one. The binary code belongs to the 3D. I make music that would represent transcendental numbers, everything in between.”

“Music belongs to the 5D,” she says, holding up her palm to reveal a tattoo of a double helix. “DNA itself is the representation of the caduceus and the lemniscate.” Referring to palm exercises in hermetic meditation, Devi’s ink becomes both a tool of worship and an ode to her sophomore album DNA Feelings from 2018, a sonic version of an alchemical practice heavy with glittering windchimes, mystic and wet-sounding vocals—not to mention a severe bass that goes so hard it becomes trance-inducing.” “I like the idea that my live shows resonate long after, in bodies, particles, and minds,” she mentions. “That it’s carried on in people’s atomic structure.”

Devi ensnares audiences with her resonant performances, and can just as easily break down the meta and quantum physics as to how she does so. For the songstress, performing live music is a way to invite crowds to join her on a higher sonic plane. “When I hit the stage, I’m already in a trance state,” she says. In addition to throat singing, occasionally whispering, and chanting, she arranges these sounds to achieve meditative states. “I become a physical resonance amplifier, a supraconductor, where my vessel reaches zero resistance to any energy and resonance. I like this terminology—it’s a little tribute to my grandfather, a supraconductivity theoretician.” The relative she mentions was Charles Paul Enz, a pupil of Wolfgang Pauli, father of the exclusion principle (fka “the Pauli Principle”), a theory which won him The Nobel Prize in 1945. Supraconductivity—as opposed to the more commonly known superconductivity, or the properties of certain substances that carry electrical resistance equal to zero—is defined as the point where electrical resistance cannot be quantified, it is infinite. “Everything is just an amalgam of frequencies,” Devi proffers, insisting that quantum physics is much simpler than the Western world has led us to believe. “Music is the arrangement of the waves governing all matter and non-matter manifestation. To me, music creates an intangible territory, an omnidimensional substance where we can exist outside of dominant rules and oppression, a world where we can detach from any pre-existing nomination and 3D corporality. It is the intangible substance to access supraconsiousness.”

Having performed at numerous festivals around the world from CTM in Berlin to her Boiler Room set in London, Devi’s music exists in a realm all its own, occasionally calling upon a community of like-minded artists in her record label Danse Noire. This summer, she’ll be debuting a new immersive live show at Sònar Festival in Barcelona titled ‘Les Immortelles’ with lighting design and scenography by Emmanuel Biard }§{. She describes her sound as “aetherave,” a term of her own creation whose prefix refers to the “fifth element” (see: ether). With thunderous and rich bass, aetherave can be best defined as cybernetically sonorous, a bespoke form of electronic music that is neither here nor there, not in a genre sense, but across binaries human and nonhuman, of old and new. “I like my vocals to feel exogenous, unidentifiable. I am using my voice to simulate the infinity,” Devi muses.

Her most recent album, Death Is Home, effectively reaches this infinity (or supraconsciousness, per her grandfather’s work), with heavy-hitting bass and synth phrases that delicately complement her resonant chants and wails. Some sounds carry out longer than others, like the high-attack drones on “Mind Era,” a head-bob-only track that feels like praying in the middle of a rave. Death Is Home is a project that can be imagined reverberating through ancient caverns, massive clubs, the few inches within your skull. “This album is synthesizing all syncretic knowledge into one piece. It’s basically an elixir of everything I know,” Devi says. “When you have to destroy your own ego, you cannot rely on your past, you cannot rely on your trauma. I had to transcend my own genesis. Creating music was creating my own universe where I would feel safe.”

Devi’s universe exists in opposition to Western society, a world she came to question during her childhood in Switzerland. “I grew up with my grandmother, a quasi-orphan as my mother was never around. My mother kept everything secret; she gatekept all information about my father. All I knew was his name, Basant Kumar Gurung,” she shares. “Western perceptions and supremacy is annihilating consciousness and exogenous knowledge. My father became a kind of hero for me, the alternative to this crippled world I was living in. I fantasized about him as a god, dead or alive. He represented this possibility of being else, being multiple.” The portrait in the Death Is Home album artwork comes from the only photo she has of him.

“I went to Nepal to look for him. I had only an address and that picture,” says Devi regarding him. “I went to [the government], they said, ‘We don’t have computerized data.’ So I went to the address and showed an old guy in the neighborhood the picture of my father. He knew him, he was his friend. He said he was a drummer and a dealer. I resonated with the whole persona.”

Two weeks after participating in a reality TV show that specialized in finding missing persons at the whim of her father’s neighbor, Devi learned he had passed away when she was still a child. “I think I already knew. Celestina, the woman who called the show, was the wife of my father’s best friend and they had a band together. She confirmed that he was a free mind, that he had a nomadic lifestyle, that he lived off of air, music, and arts. He chose a life of errance and poverty and never had a family. I really projected onto this.”

For Devi, finding levity in her electronic music is the tool to ascension. “When I produce music, I send a signal to the world, and it’s always amazing to see that when you play a show, this omniform audience is your family, your community,” she notes. “Space is an energetical organizer; space is my song arranger. My intention via music is to recall and re-initiate this connection, make people experience infinity in their body and their mental space.”

Devi is a monk in her own right, more interested in the act of transcendence, physically and mentally. Sound waves travel through her laptop perched on a concert stage, its adapters and cords and wires, thumping through the speakers of a festival stage as easily as they could be rendered acoustic in some pre-modern setting. A ritual takes place, a party is thrown; the machine-music becomes the ancestral, the human communicates not with language, but with frequencies. We want to call it spiritual, though the actual term is often thrown around by those who refuse to mean what they say. “Spirituality has become the accessory of supreme well-being integrated in capitalism, promoting it and enhancing the idea of expansion and material growth,” Devi reminds me.

She tells me civilization is collapsing, and it doesn’t feel scary. “We are transitioning to a new era, and both worlds—the old Western world and the new omnidimensional syncretic world—are colliding. Meditation, as well as mantras, reciting, and ritualistic processions are a tool of consciousness alteration, a path between conscious and unconscious, a portal to higher dimensional planes.” Maybe we are clouds made of electrons, living under the quantum law of a rave. Aïsha Devi isn’t a god, but the harbinger of this transition to beyond. Her music is the intelligent artifact, the user interface between now and the future.

Aïsha Devi’s latest album, Death Is Home, is available to listen on all major streaming platforms. She will be headlining Sonár Festival this June in Barcelona.