The eclectic Minnesotan turns Hal Bromm Gallery into a paean for nature’s simple glories

Russell Sharon has looked like many men: the pigment-dappled painter looking out peaceably over his farm in Randall, Minnesota, yet another American Spirit smoldering in his fingers; the young renegade throwing blue and gold streaks onto the abandoned walls of Pier 34 in the mild spring of 1983; the man at work lurched over a wood block not yet carved up.

Born and raised on the dairy farm to which his studio now sits adjacent, Sharon knew early on that he was tuned into a different frequency. His mother knew it too. A family member once questioned her at a get-together about why her son’s wearing pink socks, to which she replied, “Yes, Russell is wearing pink socks. He is an artist and he can wear whatever he wants.”

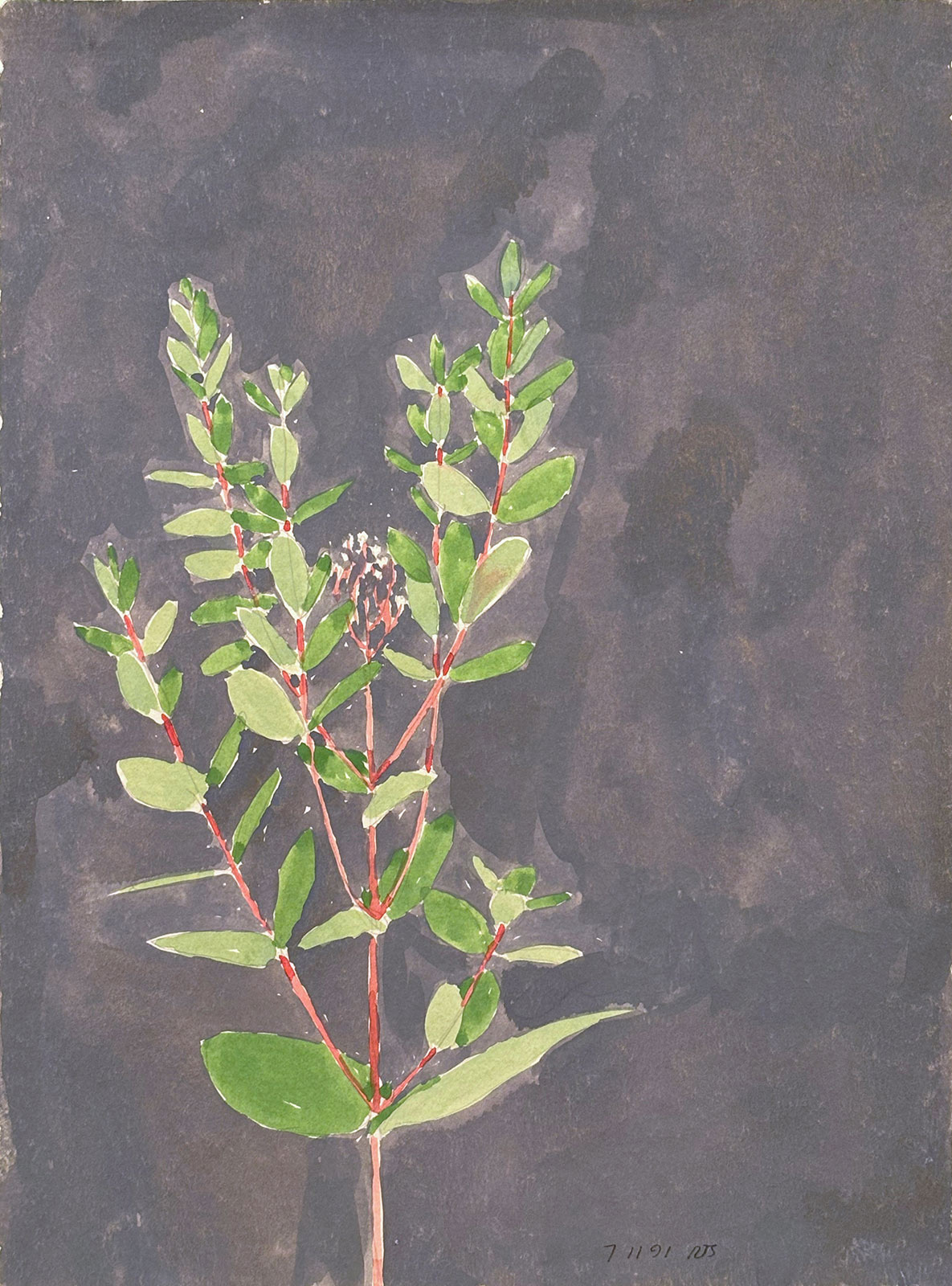

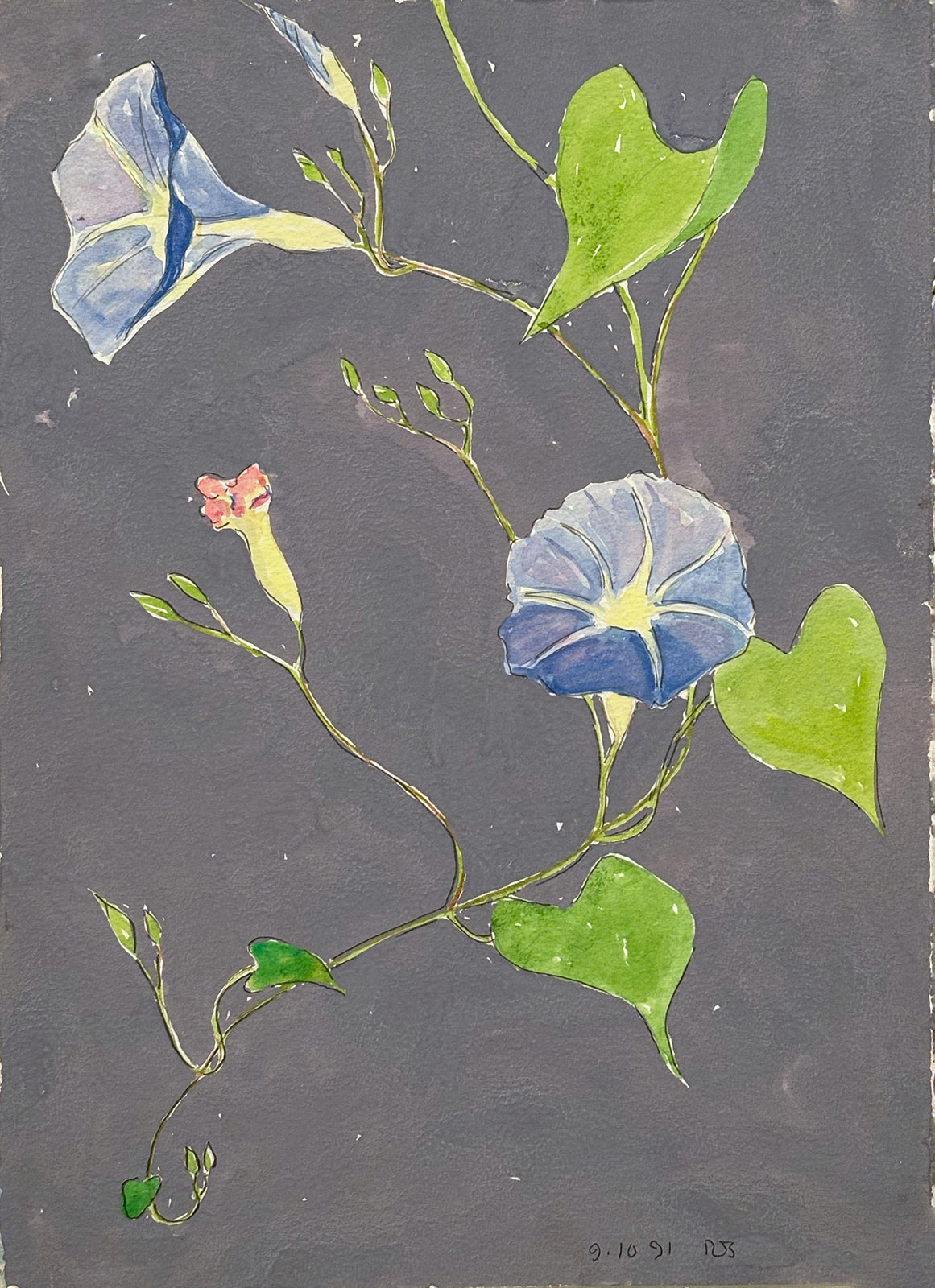

Wildflowers—on view at Hal Bromm Gallery gallery until March 31—is Sharon’s latest solo show of 22 untitled watercolors, 19 of which depict flowers Sharon found on the roadside in the immediate surrounds of his farm. Mostly executed during the summer of 1991 in rapid hour-long bursts, the wildflowers are atypical of the abstract style he was known for at the time. They’re clear, direct, about the size of an A4 page, and arranged along one wall of the gallery in such an orderly manner that they feel like the works of another, less eccentric artist. But their quality of openness and delight is typical of Sharon. “A watercolor forces whoever’s looking at it, whether they realize it or not, to add something,” he says. “To fill in the missing bits.”

A couple of vases and water glasses round out the exhibition, but the flowers, graceful and lighter than air, are the main attraction. Painted with minimal effort, they have the sprightliness of a Charles Demuth still life but from a plainer, more front-on perspective. The hanging folds of the petals, and the upward motion of the stems, are rendered in deft strokes. The uniform slabs of non-realistic ground color—a technique mastered by Van Gogh in his Oleanders—exaggerate the figurative effects: the vibrant plumage of flower petals, the shimmering liquidity of water.

Compared to his usual penchant for high abstraction, the accessibility of Sharon’s still lifes can feel a little too easy. But like the bird-and-flower paintings of the Tang Dynasty, their strength lies in their terseness, opening the viewer up to the glories of texture and fluidity produced when pigment mixes with water. “There’s something more organic about using a watercolor than using oil or acrylic,” says Sharon. “Watercolors will run together very beautifully. You really don’t have to do anything. It seems to pick up the pigment and then drop it off exactly where it’s supposed to.”

Ever since his antediluvian childhood pastor forbade him to read Voltaire or Camus (which, of course, he read anyway) Sharon has drawn solace and inspiration from high literature. In particular, the Transcendentalist writings of Thoreau and Emerson and the elemental imagery of Shakespeare have provided Sharon with an immeasurable depth of inspiration. “The writer has an illumination,” he says, “and they write it down. When you get down and read a sentence, it’s an experience that makes you warm, and makes your life more meaningful.” Wildflowers reflects Sharon’s own kind of illumination, which comes from a love for nature and beauty, and a desire to paint where the two meet. “If you like them, you call them flowers,” the artist says. “If you don’t, you call them weeds. Most people call them weeds. I call them flowers.”