Published by Hatje Cantz, ‘Weaving for Modernist Architecture’ illuminates the prodigious textile designer’s tragically brief career

Textile designer Otti Berger was a most exacting woman. The model of meticulousness, she insisted that each new design concept from her workshops—first in Germany’s Bauhaus Dessau, then in Berlin, finally in London—be devised completely from scratch. Materials could only leave the studio once they passed her judgment as a “living fabric.” She was infuriated by colleagues who confused “rug” (Teppich in German) with “carpet” (Bodenbelag). And when offers came for her to join design firms, she opted instead for self-employment, valuing her artistic independence above all.

Such exactitude flavors every page of Otti Berger: Weaving for Modernist Architecture, an ample volume of essays and images newly compiled by the German art book publisher Hatje Cantz. Readers unaware of Berger’s life or work are greeted in the book’s opening sections by a text Berger published in 1930 called stoffe im raum (“fabrics in space”). A diktat of the Berger doctrine, executed entirely in lowercase (as per the Bauhaus style), this brief text outlines several key tenets of Berger’s thinking about textiles, their design, and their manufacture. Firstly, Berger identifies fabric design with the “living tradition of architecture,” and envisions both developing simultaneously. Secondly, she emphasizes the “structure” of fabric (the word is used 17 times; the word “art” is used only once, dismissively). Thirdly, she insists upon liberating textile design from the limits of folk craft. She treats her work as a visual medium as well as a tactile one, like painting or photography done on a loom.

Born in 1898, Berger was a prodigious mind who quickly managed to top the weaving workshop at the Bauhaus School of Art, Design and Architecture. If she was a woman apart in Dessau, she was doubly so in London. The English-speaking city’s determinedly uncultivated attitude towards modernism combined with her hardness of hearing isolated her in both taste and speech. The textile craftswoman’s solace was her relationship with the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer, whom she met while he was instructing at the Bauhaus. Together they stood at the Port of Southampton in August 1938, Hilberseimer heading west to America, Berger east to visit her mother in Yugoslavia, neither realizing it was their final meeting. Circumstances dictated that she remain in Yugoslavia until her deportation to a Jewish ghetto in 1944. Some time that summer, Otti Berger was gassed in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

What did the world miss out on? That Berger died so prematurely would seem to have sealed her fate as the proverbial talent unreaped. But Weaving for Modernist Architecture makes a pretty persuasive case that, in fact, there’s more than enough in the archive to justify the publication of a 350-page tome. If you can get past the to-the-point prose style and occasional chapter headings like “Reconstructing Spatiality,” you’ll be rewarded with plenty of eye-catching expressions of what Berger hypothesized in stoffe im raum. Particularly marvelous is the cover she made for Ise and Walter Gropius’s daybed, designed by Marcel Breuer. Mistakenly labeled a “piano cover” for many years and exhibited in museums as a flat sheet of fabric, the piece comprises several fields of orange, brown, and black with subtly slanted ridges, ingeniously partitioned around the bottom edges so that, when fitted over the daybed, it seems to float off the ground.

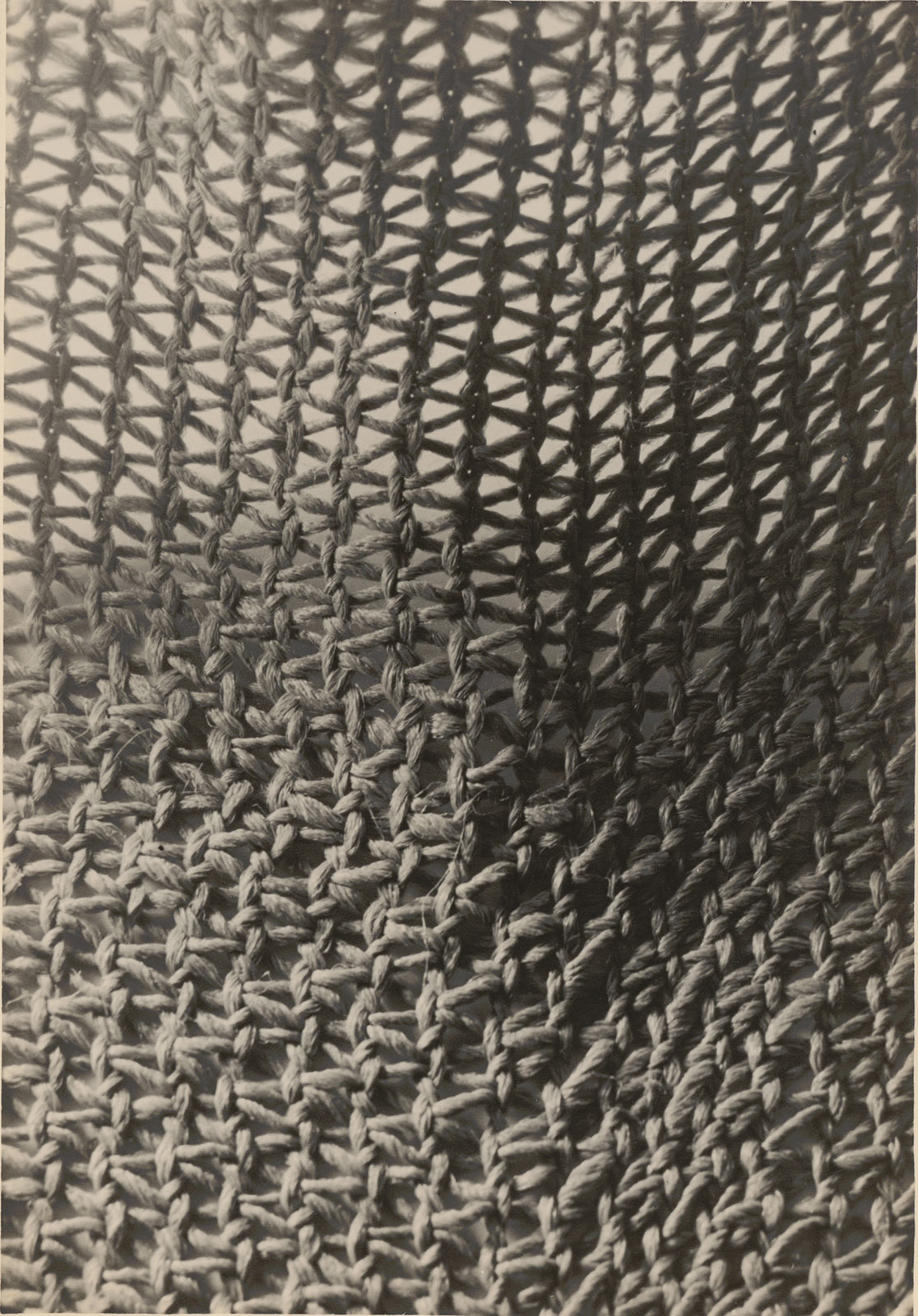

Microscopic photographs of her fabrics evince the depth and subtlety of that “structure” Berger was so careful to perfect. There are two kinds of genius this book reveals: The aesthete with a preternatural sense for color harmonies, order, and pattern across all manner of fabrics and uses; and the mind that could arrange warp and weft threads to match a carpet’s pattern to how one moved across it. This is a kind of genius you need to read the text to discover. (And for those whose weaving terminology may be a little lacking, there is, mercifully, a glossary.)

The book’s final two chapters investigate, in excruciating depth, Berger’s doomed love affair with Hilberseimer—a man who, during the war, tried incessantly to secure Berger’s safe passage to Allied territory. And it is thanks to Hilberseimer that we have this book at all. When Berger left London for Yugoslavia, intending to shortly return, she left practically her entire archive in his care. “Please,” she wrote him in September 1941, “continue to keep my things stored safely in London. At all costs, please. It’s worth it.” 83 years later, that plea has been made good. The archives, kept intact, have finally been excavated, the designs have been photographed, the essays have been written—and Berger’s work has proven, indeed, to be worth it.