The Berlin-based artist takes over multiple floors of the Upper East Side’s Petzel Gallery to uncover how gamer imaginaries shape our reality

In 1962, the Pentagon gave some cash to an MIT lab led by Steve Russell. The outcome? The first multiplayer video game: Spacewar! As with the classic speculative genre divide of books and films, gaming has often been split down sci-fi and fantasy lines. In the latter category, from tabletop games like Dungeons and Dragons onto modern 3D games like Skyrim or Elden Ring, gamers often take to combat and seek loot in, well, “dungeons.”

These spaces aren’t prisons: in fact, you may want to go there to advance the plot or earn XP. For New Zealand-born, Berlin-based artist Simon Denny, the dungeon has become a structuring metaphor for contemporary digital life. It pervades the imaginaries of tech industry NPCs who make not only games, but social media apps and decentralized-finance funds and missile-firing drones, and in turn operates on all of us.

To explore the many dimensions of the contemporary dungeon, Denny’s staged three shows in Manhattan this March: At Petzel Gallery on 67th street, he’s presenting a solo exhibition of paintings and sculptures on one floor, and on the next he’s curated a group presentation titled Multi-User Dungeon, featuring work from 1964 through this year by artists including Peter Halley, Tishuan Hsu, Avery Singer, Geneiveive Goffman, and Seth Price. And downtown at the artist-run Dunkunsthalle, he’s displaying a selection of metaverse landscape paintings.

Document headed to the Upper East Side to step into the dungeon with Denny, and to see if we can find a way out of the many on- and offline chambers we find ourselves trapped in today.

Simon Denny: So downstairs I have the solo show, which is all brand new work and then upstairs, there’s a group show that I curated. They’re both dealing with the idiom of the dungeon as a relic. Upstairs, it’s called Multi-User Dungeon (MUD), which is named after this early kind of text-only MMORPG in this format, pre-World Wide Web. For my solo show [Dungeon], I tried to pull a few examples from different moments in dungeon production, let’s say—from Dungeons and Dragons, all the way through to defense tech. There’s a lot of imagery, which is a cultural mainstay of the [gaming] context, which then also has an impact today in the design of our online worlds, because these idioms stay in the heads of the people that make these things. It’s adjacent to people who are producing online worlds, and also to those who are explicitly dungeon-producing, let’s say, like defense technology companies. I think there’s not enough attention on it. So I pulled out a few dungeon relics and made sculptures and paintings of them from various different eras.

The history of cybernetics, and game theory, and the commercial Internet is also, of course, done within the rubric of defense research and funded by the military. We don’t like the designs of those [digital] spaces that we are all forced to spend time in now. I think the dungeon, to me, came back as an origin point of that frustration. Because I do believe that cultural imaginaries produce realities.

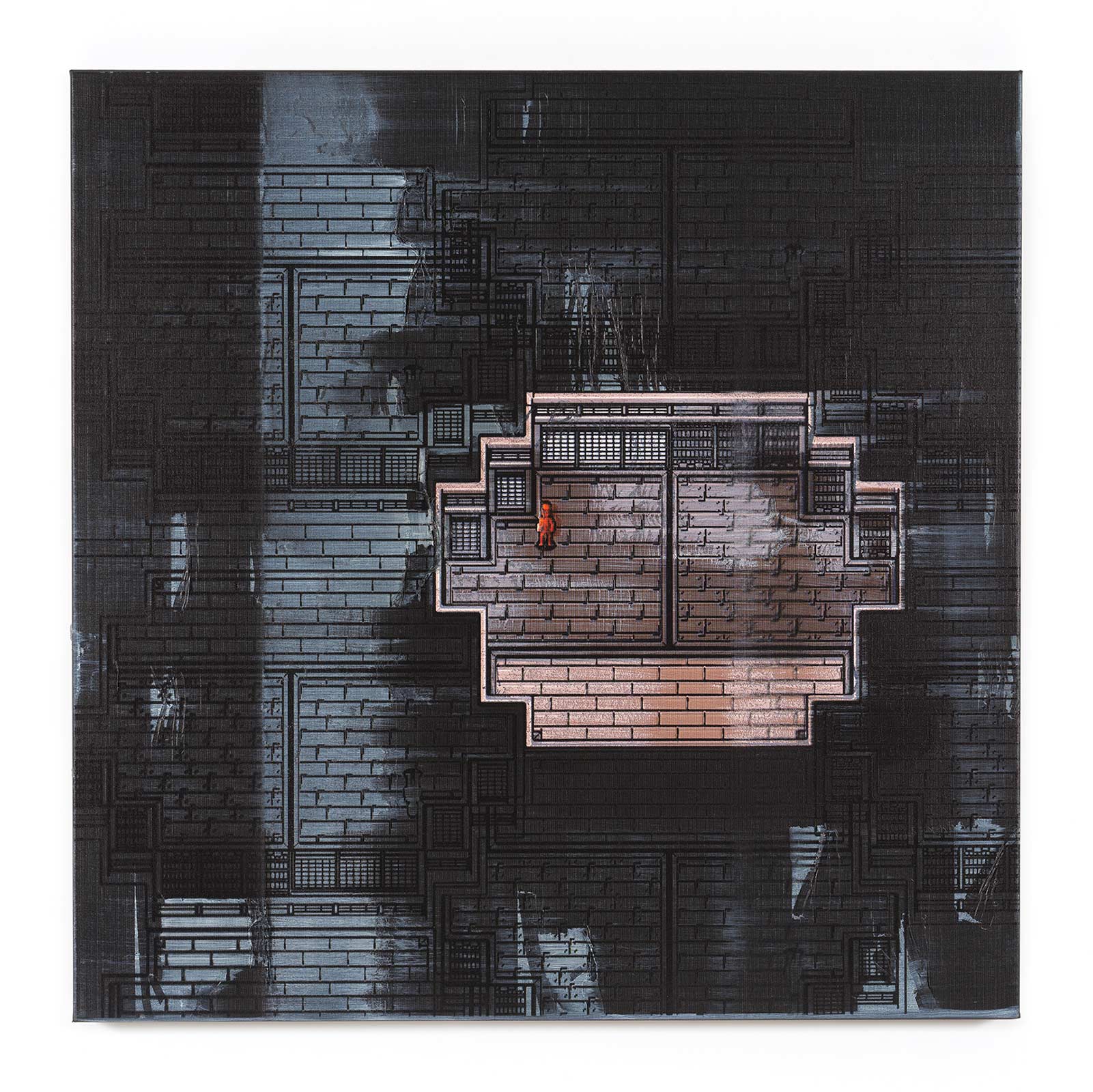

I’m a very concept-, ideas-interested person, a narrative-interested person, but also a very material-interested person.These are experiments that I’ve been doing, using layers of UV print and oil paint together. I put a layer of very thick oil paint underneath. And there are these wall-mounted UV printers now that are made for putting branding on a brick wall or something like that. I’ve been using those on top of wet paint, and then I’ve gone in and often disrupted those surfaces with a paint brush or a squeegee. And then I paint over again. You get these like very rich layerings of whatever digital print and this very gestural, brushstroke-based oil paint.

These two paintings are from a recent crypto game, called Worldwide Webb, which is sort of dungeon-adjacent. It looks a lot like an ’80s video game, but it’s from last year. These apartments that you can buy in those game worlds.

My aim for these things was to capture some of these dungeon map-style images but make them a little bit more visceral. Because I think screens can sometimes feel a little removed. I wanted to capture the feeling of what it’s like to be trapped between online and offline existences, both of which are, I would say, real. But I’m not such a virtual believer or whatever. I think they’re two different realities that have different materialities.

And this is also from a crypto game, which is more well known to those in the crypto gaming world, called Dark Forest. Then I put this beautiful early Dungeons and Dragons computer labyrinth game from 1980 superimposed on top of it. I like how this almost feels like a giant spaceship, like kind of going over the globe. The imagery is kind of reminiscent of the Whole Earth Catalog.

The show is a bit about how the logic of Dungeons and Dragons has engulfed our sociality. I like some of the descriptions one reads in more academic analysis of this type of thing, where it’s described that the dungeon is not a literal dungeon; it’s the site for life or whatever in games, and the metaphor was taken quite far away from the original meaning.

This is a bit of a compendium of Dungeons and Dragons advertising from about 15 years of comic books that I’ve collected. Some of the language is very evocative. It’s quite gendered also. All this imagery is really, really amazing, like they have some of these tabletop games, miniatures, early pre-internet computer game advertisements, but always this kind of similar language.

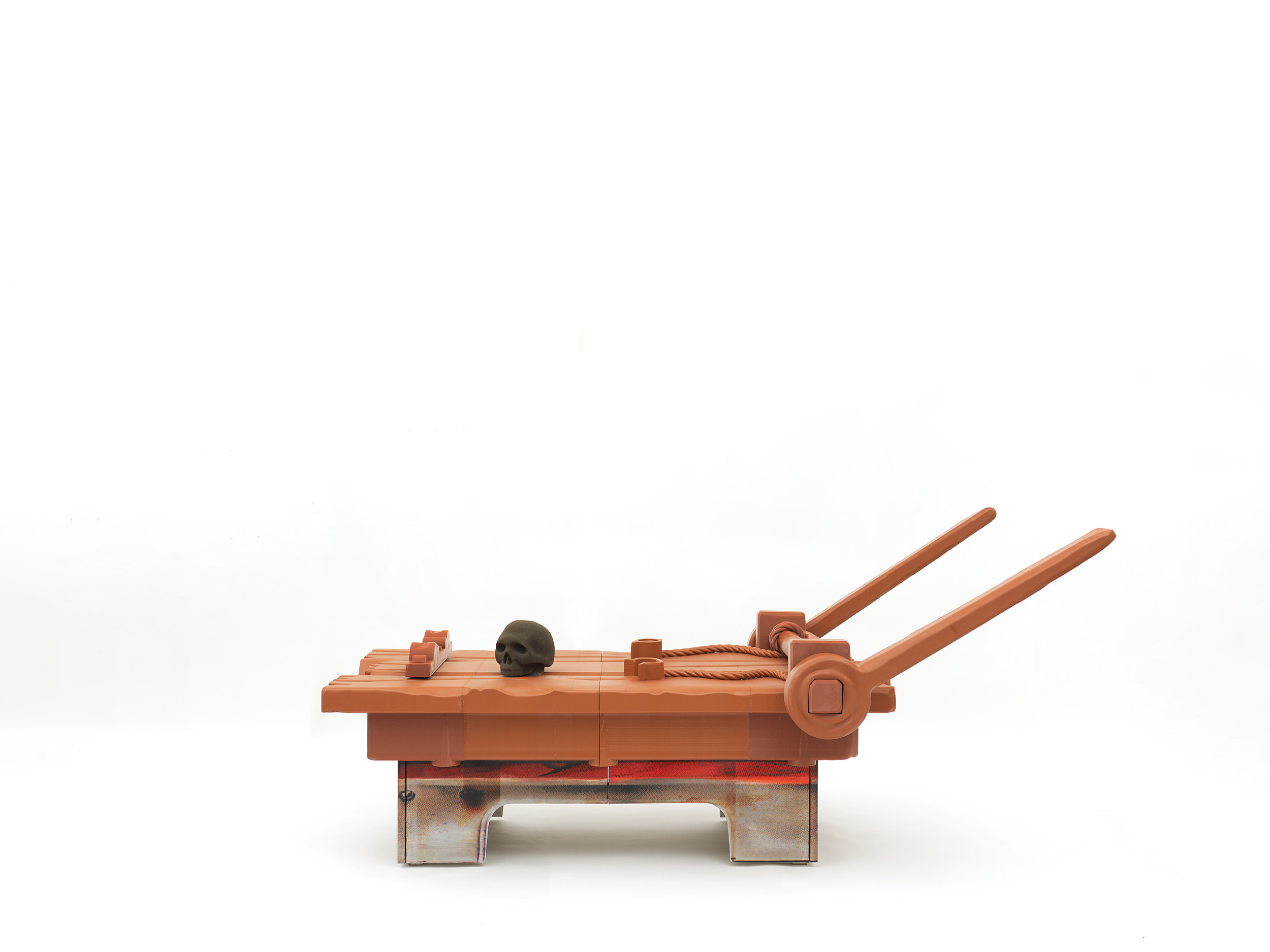

These two floor sculptural pieces here—maybe some of the more aggressive pieces in the show—are enlargements of playing pieces from this Games Workshop game from the late ’80s called HeroQuest. And Games Workshop also went on to make Warhammer and other things that expanded this world. One is a rack. And this is a dungeon bookshelf. I like the “knowledge” aspect of that. These are made with different 3D print materials that are quite rough. I really liked the artifacts on the surface; a little bit like the paintings, they have a texture to them. [The sides] are actually canvases, so you also get this weird multimedia object that is between a painting and a sculpture and a digital thing.

As you come in here, this more explicit defense tech narrative starts to emerge. This is actually a reproduction of a contemporary ad for the company Anduril, which was founded by Palmer Luckey, who started Oculus Rift first. And when it was acquired by Facebook, he was ousted, because he got involved in a right-wing political scandal. And then he started this company, which produces pilotless drones. I think there’s a VR interface to those drones as well. There’s something about developing a platform that then goes to Meta, and then going from there and developing direct weaponry, and pulling on similar language that you see in some of these Dungeons and Dragons ads. Anduril itself is the name of a sword, which explains this object, which I cast out of coffee and resin. This is a copy of a Lord of the Rings collector’s item that Palmer has in his office. And often these defense tech companies, like Palantir, draw on Lord of the Rings imaginaries. They’re talking about the West and defending the homeland—stuff that’s very adjacent to Lord of the Rings.

This is the only kinetic piece in the show, and it’s again from my collecting: The Game of Thrones t-shirt I bought from an online auction that Grimes did of her closet. So this t-shirt obviously says, “war’s coming.” I mounted it on this ironing device, which you can buy if you don’t want to iron your t-shirt, then you get this kind of dummy that inflates and pumps hot, steamy air into it. I hacked it [so it’s] two seconds on, two seconds off for like 40 seconds, and then take a minute break.

It’s plugged into a little jack there, which I got from the Twitter officers when Elon took over and liquidated all the furniture. Grimes is plugged into Elon and just huffing and puffing in there.

I like how it’s contained. And I like how the shape is a bit of a lazy body in there as well, but it’s this very aggressive imagery [on the t-shirt]. I also had Yoko Ono on my mind when I made this piece. Commodity sculpture is something that I’m very interested in as well. That history is very important to me. I think my post-internet peers were always very interested in ’80s conceptual sculpture. It’s almost as if somebody’s stuck in these dungeon walls getting angry over stuff, like we all do on social media. It sort of felt like containing the aggression.

I haven’t mentioned these two works. They’re from the Hannah Montana [version] of this game, Mall Madness. Another thing that comes to mind when I think of online dungeons and virtual worlds is [that they’re] somewhere between a dungeon and a mall. I love this kind of mall-themed board game. You run around and go to shops and buy things. There’s a swipe credit card that’s a part of the system. This new book by Chris Dixon [Read Write Own], who came out from [Silicon Valley venture-capital firm] Andreessen Horowitz, describes the three paradigms of the web. Everything is sort of like an online dungeon shop now.

Maybe one last thing I’ll point to right at the end of the space in the office, we have the last painting, which is of the Barbie world map. Remember in Barbie the film when she’s about to go off to the real world and one of the Barbies paints her a map of the real world? It’s this quite complicated map where a lot of things aren’t on it and stuff like that. I just thought the whole show has a bit of a Barbie vibe to it. It’s a little bit like my Mojo Dojo Casa House. In a way, it’s quite Ken.

Do you want to head upstairs?