For Marie Sauvage and Hajime Kinoko, rope bondage is a form of creative expression

The first time I did Shibari-style bondage several years ago, I lost sensation in my left thumb for months. This is, for practitioners of the craft, a known risk: one wrong move by the rigger, and you can sustain permanent nerve damage. It’s why a working knowledge of tying techniques is often passed from mentor to student over months or years, as was the case for Marie Sauvage and Hajime Kinoko—two Tokyo-trained Shibari artists who met in 2017, and reunited this winter for an international tour. Both are prolific in their own right, and both push their craft beyond the barriers of BDSM: Kinoko’s inventive rope installations and Shibari performances have been featured in art fairs, museums, and VICE documentaries, while Sauvage’s salon-style immersive events celebrate the female body, offering viewers a glimpse at the “transcendent meditative beauty” of a practice that has often been relegated to bedrooms and dungeons. If you google the words “Shibari artist,” their names are the first to come up.

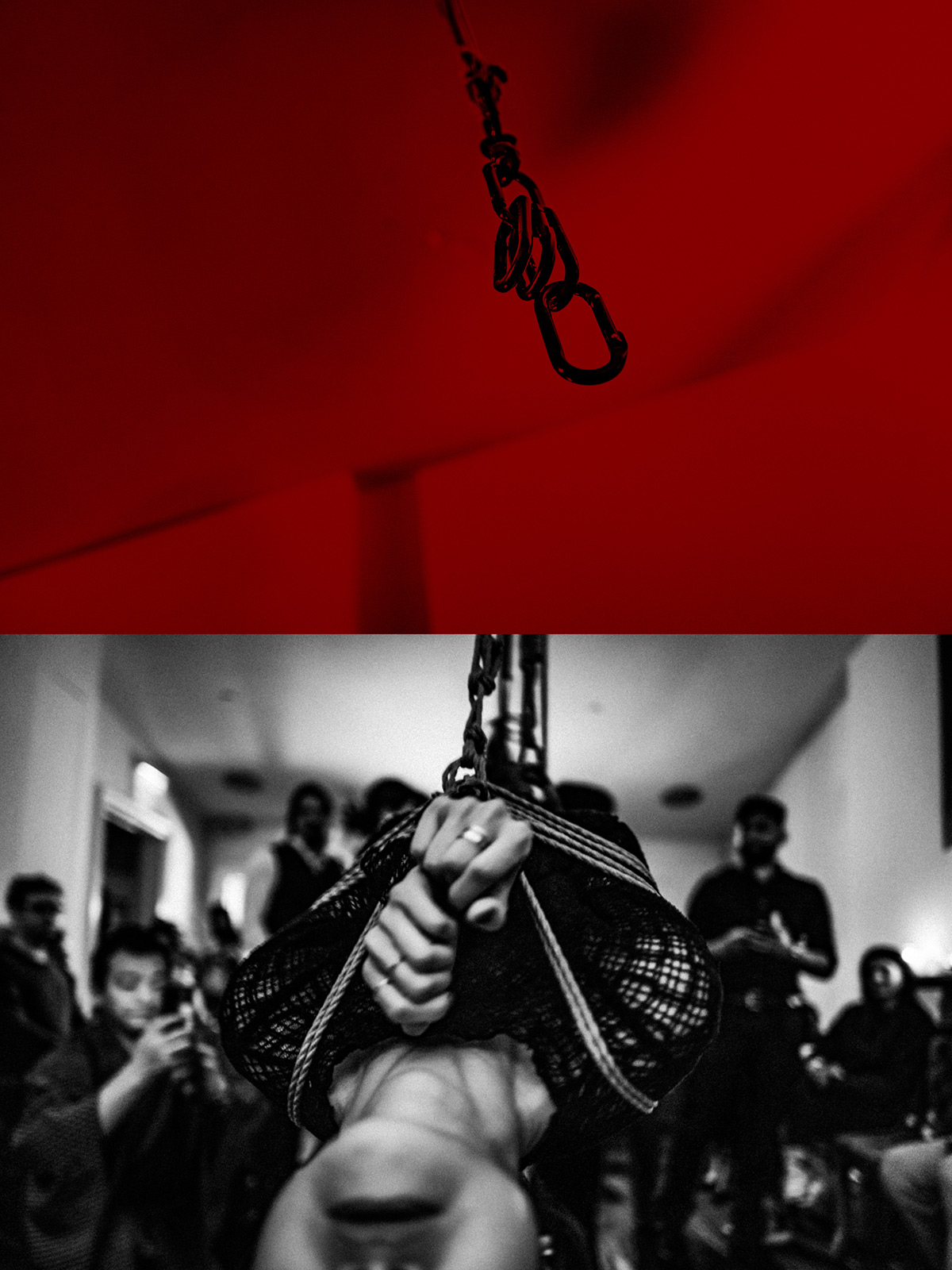

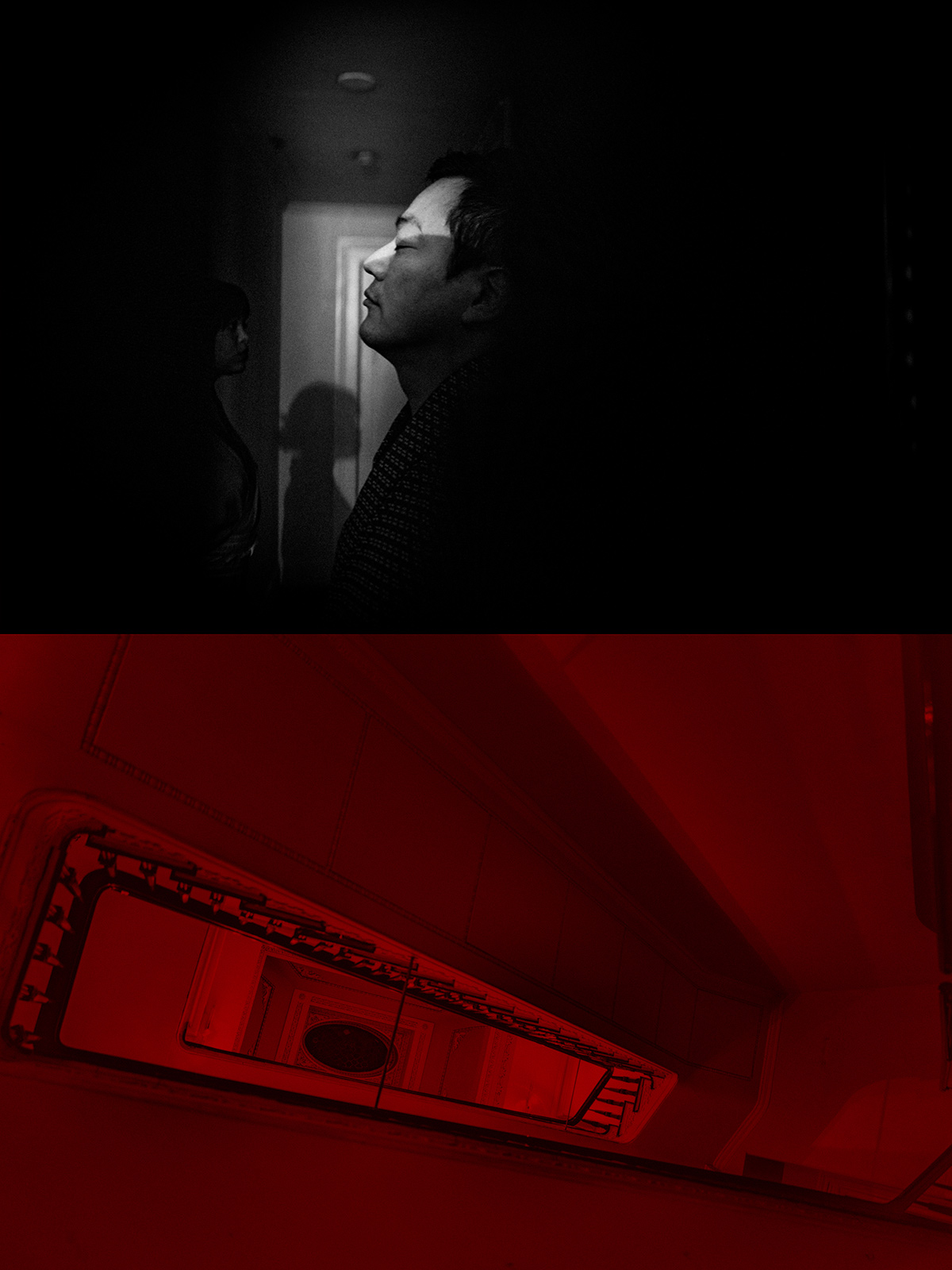

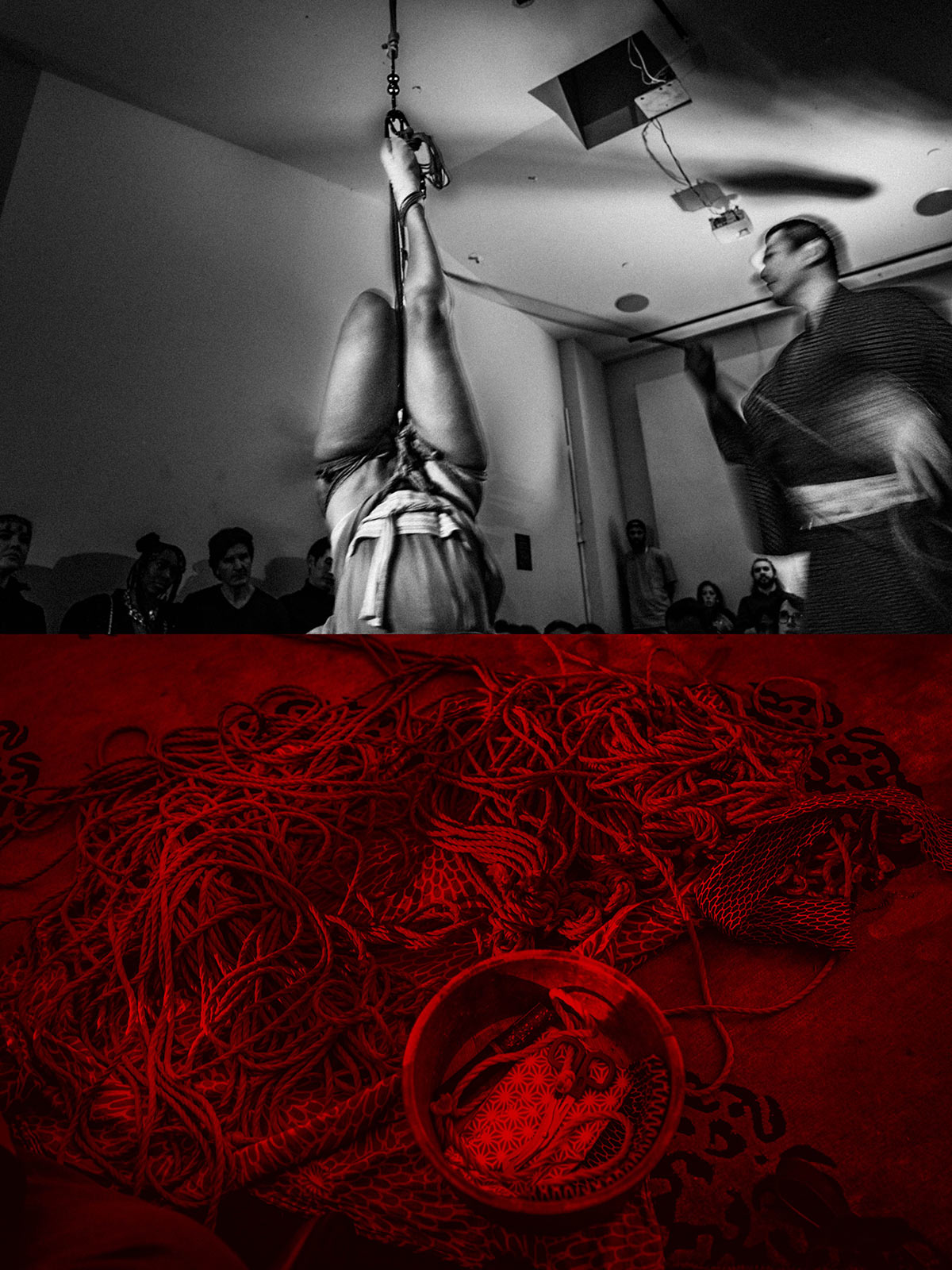

One chilly winter night, they’ve taken over a mansion in lower Manhattan; tickets go for several hundred a pop, and as spacious as it is, the place is packed. A hush falls over the crowd as Sauvage—who is one of the first women to publicly perform Shibari, and among the world’s foremost female riggers—emerges in a kimono and tabi slippers, ready to inhabit the opposite role this evening. Kinoko, who was once her mentor, binds and suspends Sauvage from the steel rig in the ceiling—using a complex and ever-evolving series of ties to twist her body into a series of exaggerated silhouettes, the intensity progressing in step with the music’s tempo.

To be suspended in rope is a physically demanding task—one my partner and I attempt for the first time a few weeks later, under Sauvage’s careful supervision. We had experimented with rope in the past but had never attempted suspension, which is among the highest-risk forms of bondage, requiring advanced knowledge of both human anatomy and tying techniques. But Sauvage makes it look easy when she arrives at my friend’s apartment in the Chelsea Hotel, pulls a seemingly endless amount of rope out of her Louis Vuitton bag, and coaches my boyfriend through the complex series of ties required to safely suspend the human body. An hour or so later, I’m gently swinging from the steel ceiling rig, the rope guiding me in slow circles like the string of a marionette.

The feeling is, to my surprise, almost exactly what I imagined: an experience of acute embodiment, the intensity of which is emphasized by the sharp bite of jute around my limbs and the inevitable surrender that comes with seeding all physical control. Being suspended in rope is, above all, an exercise in trust: “When you’re tied, either you panic, or you let go,” Sauvage says. “In the beginning, you think, This is scary, I’m out of control—but when you trust your rigger and realize you’re afraid for no reason, there’s an endorphin rush and your muscles relax. By the end, it’s like you’re floating on a cloud.”

“There is a subcategory of Shibari that is about sadism, really pushing the limits of the body. Some people are into that. But I think what a lot of people want is to learn how to be vulnerable.”

Sauvage is intimately acquainted with both sides of this dynamic, having spent hours bound by Kinoko during his international tour, often in front of an audience of hundreds. The pair tell me that, during a performance, the model can become a kind of muse: “If the person is trusting you and enjoying the way it feels, even if it’s uncomfortable, then you are inspired to do more and make it more beautiful.” Kinoko says that, when working with a fellow rigger like Sauvage, he has the creative freedom to improvise new ties and transitions with confidence, knowing she’s well-equipped to follow his lead. “He improvises a lot—and this amplifies the surrender aspect of the performance, and creates a sense of emotional intensity,” she says.

During a suspension session, Kinoko and Sauvage are attuned to dozens of tiny details: from the model’s movements to the temperature of their skin, which can indicate their body’s limits even before they’re aware of them. I experienced this firsthand when—after hanging upside down for several minutes at the Chelsea—Sauvage detected a spike in my body temperature and swiftly untied the ropes just before I began to experience a faint ringing in my ears. It’s a common physical response for first-timers—and after a few minutes horizontal, I was back in the saddle, having also experienced the potent cocktail of endorphins that keeps people coming back again and again.

The word Shibari—meaning “binding” or “tying”—came into common use in the West in the ’90s to describe Japanese-style bondage, also known as Kinbaku. Though now used to describe a practice that focuses on the aesthetics and display of the body, many of the rope patterns associated with Shibari derive from hojōjutsu, a tying technique originally used in the Edo period to arrest, restrain, and torture prisoners of war. Though these ties have since been modified for greater comfort and safety, rope bondage is often still associated with elements of BDSM, namely erotic humiliation and dom/sub dynamics. But artists like Sauvage bring a different tenor to the practice: “There is a subcategory of Shibari that is about sadism, really pushing the limits of the body. Some people are into that. But I think what a lot of people want is to learn how to be vulnerable,” she says. “So I see Shibari going in a direction that is more artistic, a bit more spiritual—almost in the direction of self-help.” Kinoko agrees: When he first started performing 25 years ago, the audience for Shibari shows was composed mostly of people in the BDSM scene. “Each year, there would be 20 percent more people who were not just from underground communities,” Kinoko recalls. “Now, Shibari performance is interesting to the mainstream.”

Kinoko first learned Shibari at the request of his then-girlfriend; he channeled his chiropractic training toward the development of new tying techniques, and 20 years later, he was Sauvage’s first introduction into the world of rope. Before that, she had been in the fine art world and orbiting New York City’s kink scene, but had yet to find her niche. “My whole life, I was always just slightly sexually obsessed. And I felt it wasn’t fair that women were not allowed to embody this natural impulse—but I didn’t know what avenue I was going to express that,” she recalls. When she witnessed the burlesque legend Dita Von Teese perform in her early 20s, she realized she, too, wanted to be onstage. “I didn’t feel like burlesque was my thing, and I love Shibari because it’s about trust. It’s about connecting with other people. It’s a really meaningful life to inspire people, especially in a world that’s so sex-negative.”

In the past, Sauvage has said that she didn’t want Shibari to go mainstream because the sensual nature of the practice could get lost in some way. But having witnessed the censorship of her content over the years—particularly on platforms like Instagram—she now feels strongly about combating the threat of conservatism by drawing awareness to different aspects of Shibari and bringing it to broader audiences. Kinoko, too, celebrates the increasingly diverse groups of people who, like him, see the art in Shibari. A photographer as well as one of the world’s most esteemed Shibari masters, his work has brought him to countless venues around the world—including the Museum of Sex, where he staged a Shibari performance to accompany an exhibition by Nobuyoshi Araki, an artist who often memorialized the transgressive beauty of rope bondage in his work. Kinoko’s art also extends beyond binding the human form and into immersive web installations, in which he often situates and suspends his models. At a recent event, 700 people crowded in to see the pair perform: “We need a big monitor so everyone can see, like at a concert,” Kinoko laughs.

Witnessing the world’s response to these Shibari performances, it’s clear that the desire to be bound is a common one—and whether for sexual gratification or emotional catharsis, rope can be a powerful tool of self-discovery. This is what keeps Sauvage and Kinoko practicing, year after year: “I was inspired to adopt an art practice that has to do with the body that makes people feel so empowered and liberated, even healed,” Sauvage says. “It’s not just sexy and beautiful—it’s also really meaningful for people.”

This is true, too, when Shibari is applied toward kink. The boundary between pain and pleasure is, for many, as thin as the rope that binds them—and in their performances and workshops, Sauvage and Kinoko create a safe space for first-timers to surrender their defenses. Often, the experience unlocks something inside of them, Sauvage says; the intense physical sensation of being bound, coupled with the heightened emotional vulnerability that comes with it, can make some people feel drunk afterward, or push them toward emotional breakthroughs. “Their reactions can be so visceral and moving. Sometimes, people will cry, because there’s this sense of catharsis. At one event I did a week ago, a woman came up to me and said, You changed my life,” Sauvage recounts. “At the end of the day, everyone wants to connect and be vulnerable—and the way we do Shibari, it’s about learning to trust.”