Whitney Mallett reports on the East Village institution’s 12-hour marathon variety show of unhinged spoken word, absurdist musical sets, and unsettling dance numbers

At 6.07 in the evening on New Year’s Day, a line snaked out the doors of Saint Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery and around the block. The second half of the Poetry Project’s 12-hour marathon reading had only started seven minutes before and already there were so many people waiting in the cold to get in. “It is the 50th anniversary,” a scarved and bundled woman in front of me hissed to her partner, suggesting that the semi-centennial of this dawn-of-January ritual explained the overwhelming crowd. The gathering has ballooned over the years from 30-odd readings in its inaugural edition to a day-long affair featuring 150 performances this latest iteration, a beatnik spectacle combining free jazz, modern dance, and the spoken word.

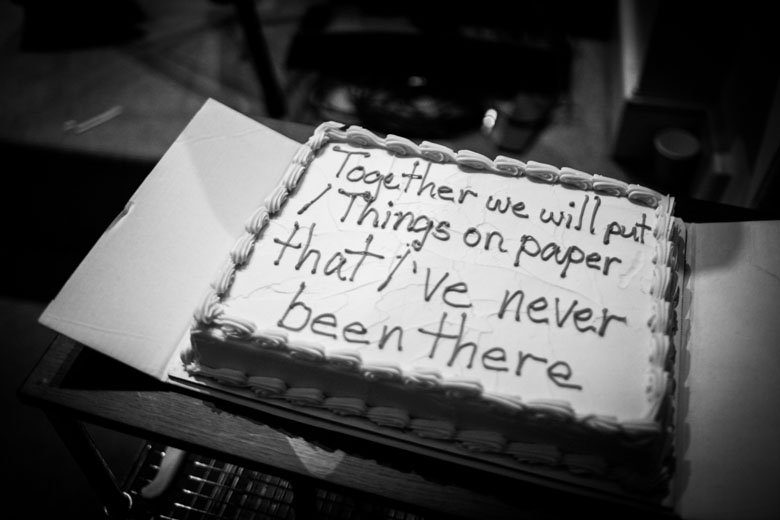

“It’s always been political,” explained poet Anne Waldman, who conceived of the first marathon, January 1, 1974, and its variety show format. Back then, Waldman (who performed Monday) was the director of the Poetry Project, an arts nonprofit headquartered at the Saint Mark’s Church since its founding in 1966 (the congregation’s radical history also includes initiating a Black Panther Party breakfast program a few years later). “The marathon was anti the Vietnam War back in those early years,” Waldman recounted, and it continues the same ethos to the present day, this year’s installment fueled by both outrage and grief about the war on Gaza. Also threaded through the program was an insistence on the critical role that art and imagination play in building a more liberatory future. Kyle Dacuyan, who closed out his six year tenure as the most recent director of the Poetry Project during Monday’s pageant, gave a speech offering a vision of poetry as socially and politically vital—a practice that continually “articulates the unfathomable horizon” and “enlarges the way we live with one another.”

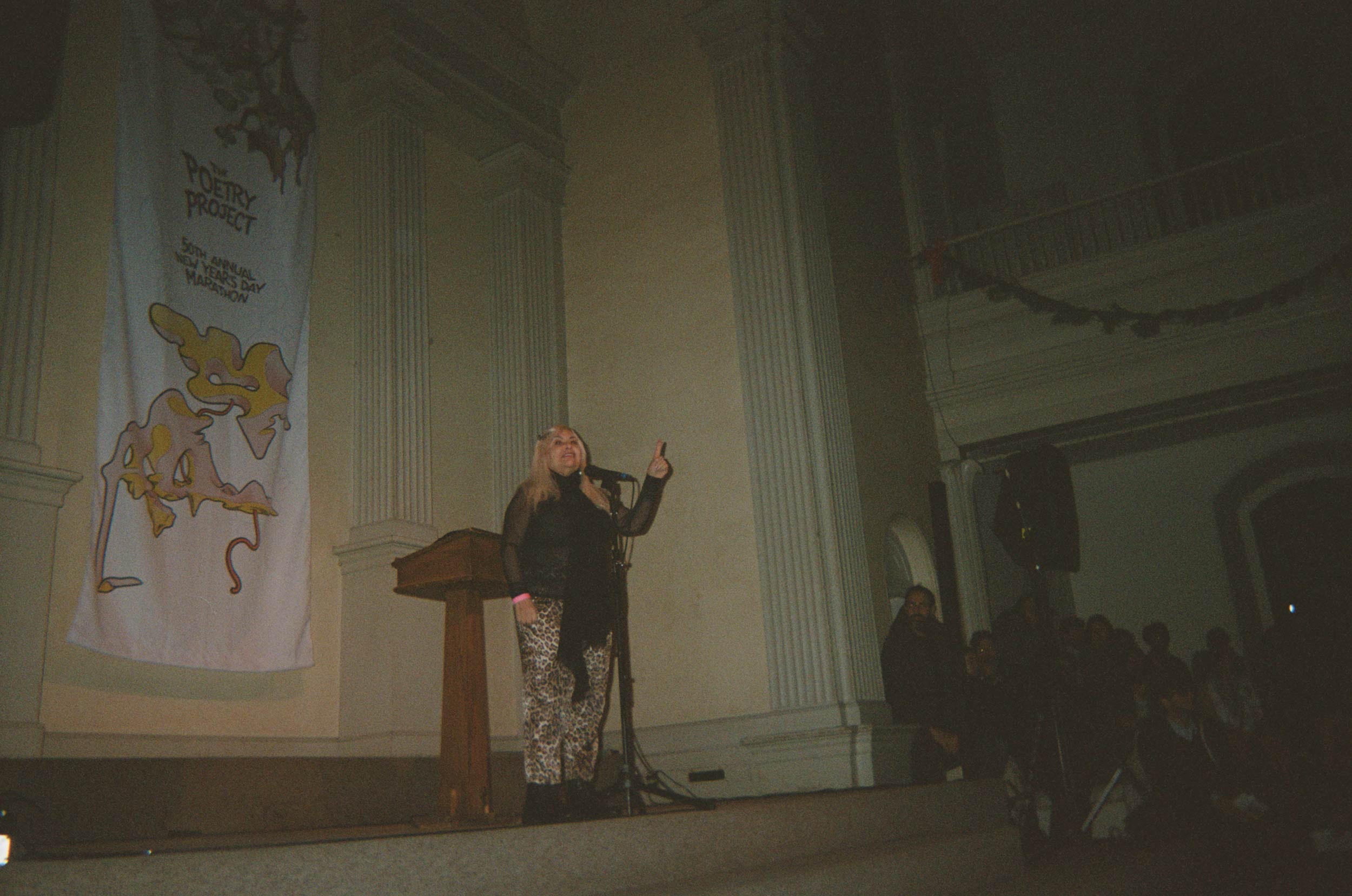

As icons like Fred Moten, Karen Finley, Patricia Spears Jones, Cecilia Gentili, and Chelsea Manning took to the altar-cum-stage; textures of text were everywhere. An accessible speech-recognition feed projected readers’ words as they rang out in the jam-packed sanctuary, sprinkled with glitches like “KHREUS mass.” Unhinged legend Penny Arcade wore a toque stitched with old-west lettering that spelled out “GEM SPA” (the 73-year-old actress took the persona of a beggar with a blaccent for her performance, an excerpt from a one-woman show she’s doing at Joe’s Pub later this month). The Gumby mascot responsible for resetting the mics and podium between sets donned a football jersey nameplated “HE HATE ME” (I was baffled, but my sports buff father immediately identified the jersey as belonging to Las Vegas Outlaws player Rod Smart in the short-lived XFL league via text). Later, artist Leah Hennessey threw down an absurdist-dandy singer-songwriter set playing acoustic guitar in a Colette T-shirt screen-printed “VICTORIAN PUNK.”

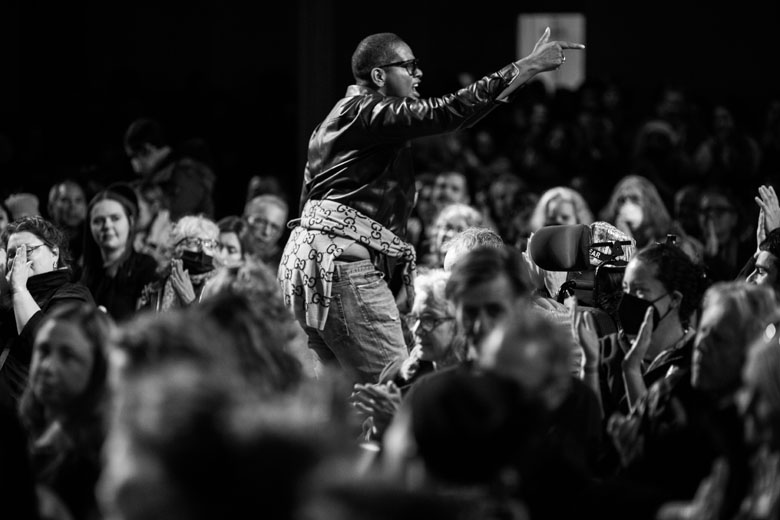

The electricity in the room swelled at around 8.30 when poet Cuthwulf Eileen Myles closed their performance with a call and response that got the thousand-person audience barking like dogs. Somehow, the momentum spiked even more when poet Pamela Sneed took over and, in a searing poetic critique, read Barbie to filth. Sneed unpacked how Greta Gerwig’s film was white-centered and sanitized, but also urged, her voice straining raw: “We need her right now for Gaza and Palestine. We need Barbie now!” These rockstar sets in tandem crystallized the Poetry Project’s pronouncement that, for 50 years, their signature event has been “rowdy, enduring, and improbable.”

The marathon from its inception—according to Waldman—was shaped around asking community members “what is your new wisdom, what luminous detail or nugget of poetry do you have to offer?” The resulting performances generated “a sky of constellations that created a connectivity for the coming year.” This event has also functioned over the years as the Poetry Project’s main fundraiser; Monday they raised over $79,000 through ticket, book, food, and drink sales as well as online donations. From the beginning, the benefit has been “crucial” for making possible “the ongoing ‘antithesis reality’ of the downtown ethos,” Waldman added.

The marathon’s potpourri of performances is, by design, both intergenerational and full of surprises. “Everyone is bound to see something that astonishes them, and that deeply bores or offends them,” said Dacuyan. Some of the most successful and unsettling performances this year (imho) were three dance-based numbers by Malcolm-x Betts, Tess Dworman, and Yoshiko Chuma, respectively. Chuma, who’s a veteran of the marathon, “intuitively recognizes this wavelength that poetry and dance are on together,” continued Dacuyan. “She’s really comfortable in this position of being misunderstood or out of reach. I’m always curious to see what stunt she’s going to pull. This year it was taking the camera out of The New York Times photographer’s hands.”

By about 9.50, playwright and actress Emily Allan took the stage, making a childhood dream come true. She’s been coming to the marathon almost every year since she was a kid in the ’90s, and her synthy artrock song about a creative couple’s downward spiral was a palpable hit among last Monday’s throng. “I’m now obsessed with you, Emily Allan,” gushed Gentili, the hour’s host (each hour is helmed by a different poet). Later Allan wrote to me about the fraught relationship she’s had to the event, and how sublime this moment was for her:

I used to describe the feelings I would have in that room as a young person by comparing them to the descriptions of someone coming into their sexuality in a 19th-century novel—a mysterious and confusing mix of repulsion and attraction, an overwhelming feeling of ickiness and resentment and horror, mixed with an undeniable magnetic attraction, a yearning to become, a libidinal calling. Susan Sontag talks about reading or hearing someone’s writing that you feel that YOU should have written, and you feel so close to the conception that you feel the labor pains. I used to feel major, major stripes of pain at the Poetry Project, and then I would talk about how I “hated” it.

Then later, when I was older and I saw more scene-y young people from other spheres of my life read, I had a different kind of resentment, like, why do they get to do it when I’ve been in the trenches all these years? Even though I wasn’t taking any steps to be a reader, and I wouldn’t have had anything to read. It took me a long time to realize that these feelings are not unique and they just meant I had to sit my ass down and try to write some crap and suffer just like everyone else.

So it was completely sublime to take the stage last minute when someone dropped out this year. I love the ritual and the complicated feelings and the sacred and the profane and the eye rolls and the awe and the genius—all of it. And I loved reading, I hope I get to do it again.

In Dacuyan’s words: “People come to the project because they have a sense of story that precedes their arrival. It’s beautiful.”