The actor and directer spotlights genre-bending shorts from New York filmmakers featuring Illuminati P.I.s, a fallen angel, and a not-so-magic rodent

We were given white roses before we descended. People filed in, slowly. The lights dimmed and the title card came up without introduction: Lemon Tree, directed by Rachel Walden. The movie launched a cinematic evening titled Mirage, programmed by Erin Grant, Jill Ferraro, and Emily McEvoy, for the NYC premiere of Grant’s directorial debut, Zero at the Bone. Spanning genre and mood, the three shorts were united, in mirage-appropriate spirit, by distorting perception and reality.

Lemon Tree opens with a magician taunting a child (played by Gordon Rocks) and his father (Charlie Chaspooley Robinson)—leading to a tussle in which the dad absconds with the magician’s rabbit. We then watch the pair’s journey back home. Meditative, affecting, and unexpected, the film debuted in 2023 at Cannes. With its comparably realist disposition, Walden was at first surprised at her being curated into the Mirage evening. “I had never thought about [Lemon Tree] in that context, but seeing it next to the other two, I realized there is disillusionment about the expectations of the day, and how it turns out to be something totally different,” Walden said It’s a mirage of the child’s own idea of how the trip is going to go as it becomes this total nightmare.” The screening, she reported, made her think of her own film in a fresh, more ethereal light.

After Walden’s short, Emily Allan and Leah Hennessey displayed the 2021 piece they’d written and directed, Byron and Shelley: Illuminati Detectives. As the title suggests, it depicts the duo (played by Hennessey and Allan respectively) on the hunt for an alleged Lamia, a snake-like mythological being who’s turned a man to stone in Switzerland. For the pair, making the film—in an ecstatic post-lockdown fugue—was a mirage itself: “It was an oasis of vision for us,” Hennessey recalled. “It was the sci-fi pastoral idyll that we fantasized about throughout isolation.”

Allan and Hennessey had previously acted as the poets in their two-person play Slash—and when a residency at CERN brought them to Lake Geneva, the project felt fated. (The research center is a short distance from Villa Diodati, where Mary Shelley and John William Polidori invented Frankenstein and the modern vampire on one spooky 1816 night). With its X-Files-gone-haywire tinge, Byron and Shelley premiered as part of 2021 Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement, curated by art collective DIS with Andrea Bellini, in which artists were invited to propose “pilot episodes” of TV shows in a blend of video art, installation, and narrative cinema. “Emily and I started believing that we were Lord Byron and Percy Shelley,” she admitted. “We really conjured this alternate space and this Arcadian vision.”

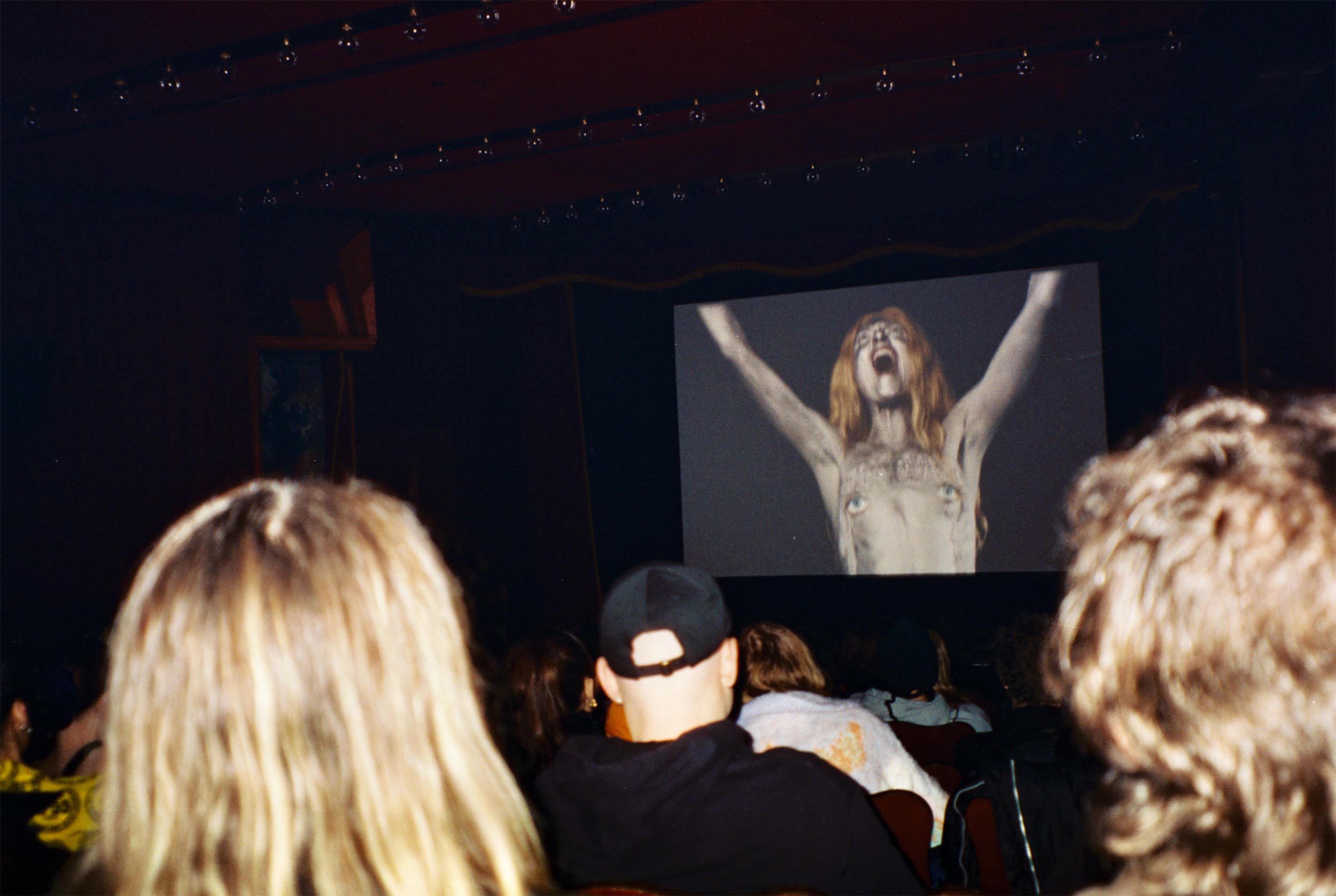

The screening ended with Grant’s Zero at the Bone. In it, we’re taken to an isolated desert landscape (shot in Southern California) in an indeterminate time. An angel has fallen; someone’s blown up heaven. The film follows her detention and release by the only other character, who lives in a tent on the dunes, played by Géza Röhrig.

Zero at the Bone premiered in October at Sitges, a genre-focused festival in Catalonia. Grant noted that the original intent wasn’t to make a project that would be dubbed sci-fi, but the term kept coming up as she developed the project. “I really think of it as post-apocalyptic, but there are a lot of sci-fi films referenced. Not movies with aliens, but others that were more down to earth and had a certain minimalism to them.” She also called out acid westerns as a favorite genre, which inflected the short and the stylization of its dialogue. The costumes, designed by Lyndsea Lamarr, and the props, designed and handmade by Elysia Belilove, also highlight the piece’s genre play: “We wanted objects that felt like they could either be from far in the future or ancient,” Grant explained. Not-quite-’40s-looking radios coexist with mysterious orbs that open portals to the afterlife, for example. “We asked what it felt like to mix different time references to create something classic and timeless that also felt specific and helped create a cohesive world.”

In addition to writing, directing, and executive producing, Grant played the film’s angel. “I love acting and I think I also am a little bit of a masochist in that I like being involved in all parts of the process. You have to pull from many different disciplines to make something feel full. The experience of acting is so different from writing or directing or editing. It’s so immediate and, maybe it’s cliché to say, it was really cathartic.”

Grant—who organized the evening along with producers Ferraro and McEvoy—explained that she’d always been drawn to the “fantasy and ephemerality” of mirages. “They’re so beautiful and evocative, but also sad,” she said. “There’s something very desperate, and I feel desperation and desire are two very interesting, close emotions to me.” Despite the diversity in style and content between the three films, Grant felt they each addressed fantasy in unconventional ways, approaching the theme from different directions to present a fuller picture on its contemporary potential.

During the Q&A, moderated by Ruby McCollister—who also played Claire Clairmont in Byron and Shelley—the filmmakers discussed their unique challenges (children and animals; sand; pandemic madness) and their inspirations (a grandfather’s story; divine inspiration in a Greenwich Village CVS; pandemic madness), before we were quickly shooed away by Roxy Cinema staff: nobody noticed we’d gone over schedule—it was time to party.