The artist shares a list of books, compiled during her fellowship at Headlands Center for the Arts, that helped inspire her latest exhibition, ‘Climate Futurism,’ at Pioneer Works

Using a variety of media—photography, sculpture, historical artifacts—artist Erica Deeman explores how Black identities have been shaped over generations. Whether photographing others or turning the camera on herself (as she does in her series Self Regard), Deeman’s subject matter principally concerns itself with approaching Blackness with distinct kind of care. While her photographs are visually compelling, Deeman deals primarily in ideas.

Those ideas are inspired, in part, by the heritage of the African diaspora. Deeman was born and raised in Nottingham, England, and her maternal family came from Jamaica as members of the Windrush Generation, a term used to describe the mass migration of Caribbean people to the United Kingdom in the ’60s via a ship of the same name. After studying public relations in Leeds, Deeman left Britain for the United States to dedicate herself fully to art, graduating from San Francisco’s Academy of Fine Arts in 2014. She now lives in Seattle, and her artworks stand in the permanent collections of institutions like Berkeley Art Museum and New Orleans Museum of Art, among many others.

Autumn has been a busy season for the artist. Based around the concept of movement, Deeman presented Emerging States, a series of self-portraits at Anthony Meier gallery in San Francisco, and currently, her installation Give Us Back Our Bones is now on view at Pioneer Works in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Co-presented by the Headlands Center for the Arts—an international arts center best known for its dynamic public programs and highly lauded artist residency—her new exhibit Climate Futurism gestures toward unwanted horizons presented by a tenuous environmental state. Writing for The Brooklyn Rail, Alec Turnbell described Deeman’s installation—which resembles an ominous mobile—as a kind of “glass through which the past and future can be seen, darkly.”

As Climate Futurism draws to a close, Deeman catches up with Document to provide recommended reading on the state of what some call ecologically disastrous. Much like Deeman’s own work, these titles turn to the past as a way to better understand this concept, rendering a present notion of impending environmental doom moot, in favor of a hopeful environmental future.

Reorientations; or, An Indigenous Feminist Reflection on the Anthropocene by Kali Simmons, It’s Not The Anthropocene, It’s The White Supremacy Scene, Or, The Geological Color Line by Nicholas Mirzoeff, and Caretaking Relations, Not American Dreaming by Kim TallBear

Give Us Back Our Bones is inspired by Jamaican farmers and fishing communities, as well as my family’s voyage from Jamaica. There is the need to return to a different way of thinking that sits outside of white supremacist notions of land ownership, nature hierarchy, capital and patriarchy. The three essays listed above advocate for decolonization and question how our collective thinking has been co-opted into notions of catastrophe. Ultimately, the authors lay bare the belief that our climate futures have been molded by social structures, and propose that social justice is an integral part of building better futures.

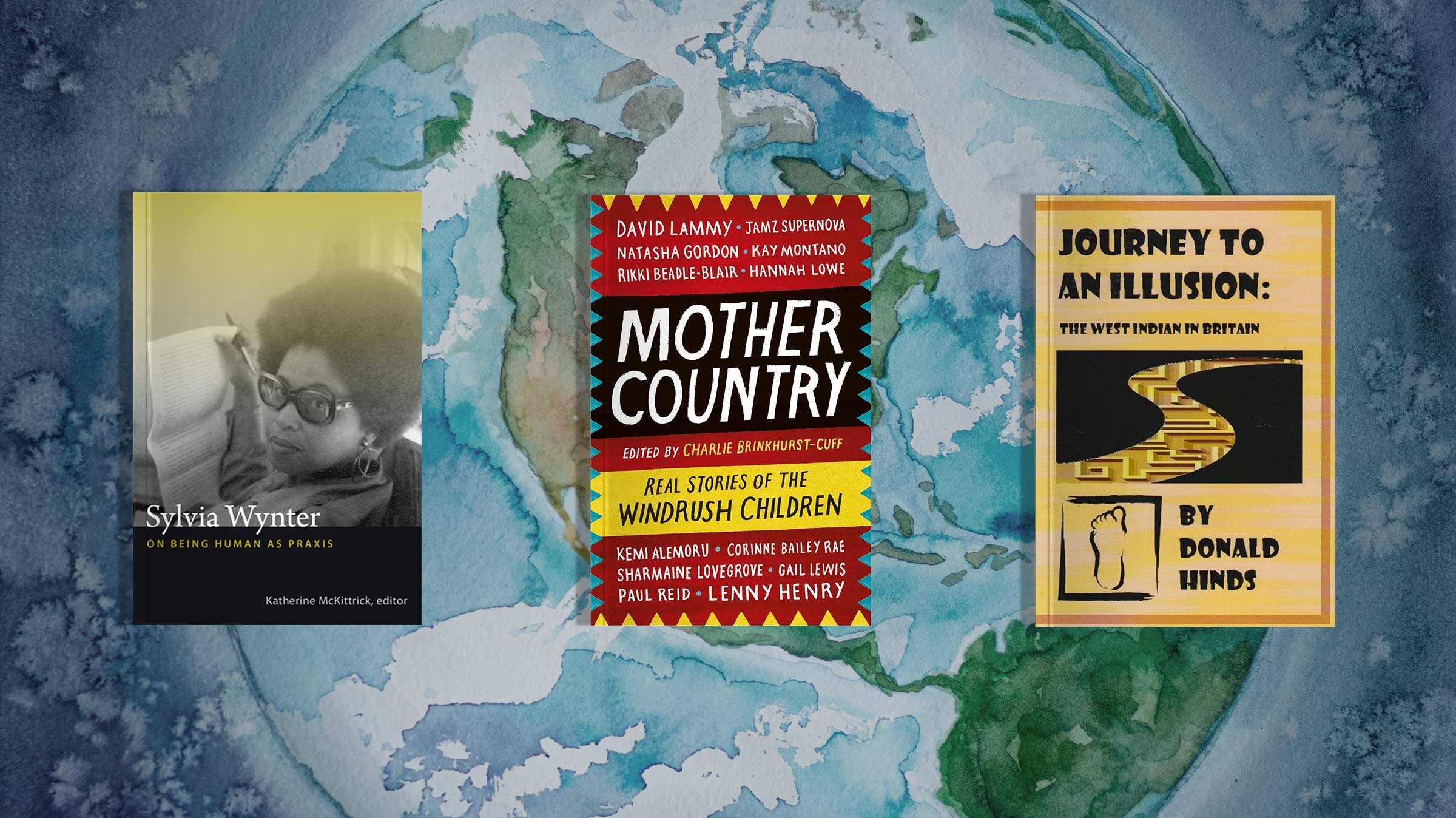

On Being Human as Praxis by Sylvia Wynter

Sylvia Wynter is a Jamaican cultural theorist who offers a portal of contemplation through the archive of history, literature, science, and Black studies,while examining colonial legacies. Her insights on race, location, and time offer readers space to consider what it means to be human. Wynter reminds us that the modern concept of ‘man’ is incredibly young. She offers us insight and a way to re-historize the qualities that make us human. The essay Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species?: Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future is a conversation between Wynter and scholar Katherine McKittrick about decolonization narratives—it’s mind-blowing.

Journey to an Illusion by Donald Hinds

This book is a series of interviews conducted with Caribbean people upon their arrival to the UK as part of the ‘Windrush Generation’ in the ’60s. I am struck by the candid nature of the stories. Donald Hinds also came from Jamaica to the UK, and whilst working on buses he founded a newspaper called West Indian Gazette—Journey to an Illusion is the product of years of reporting. Reading the book, I am struck by the resistance of a people who helped rebuild an empire after World War II, and both the grief and heartbreak that resulted from the racism they endured. Community support enabled them to keep moving forward.

Mother Country by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff

This eloquent memoir-like book also centers on the ‘Windrush Generation.’ There is a quiet confidence and joy to many of Brinkhurst-Cuff’s stories, as well as perseverance, heartbreak, and possibility. I am intrigued by the comparison of the stories held in Journey to an Illusion, and how time has played into the narration of the storyteller’s journey. I think of my own family and their passage. Though their story is not directly written, the voices in the book offer a reflection of a time and a struggle. We continually seek to find ourselves in others, and this book offers that space for me, and for a future that builds from this community.