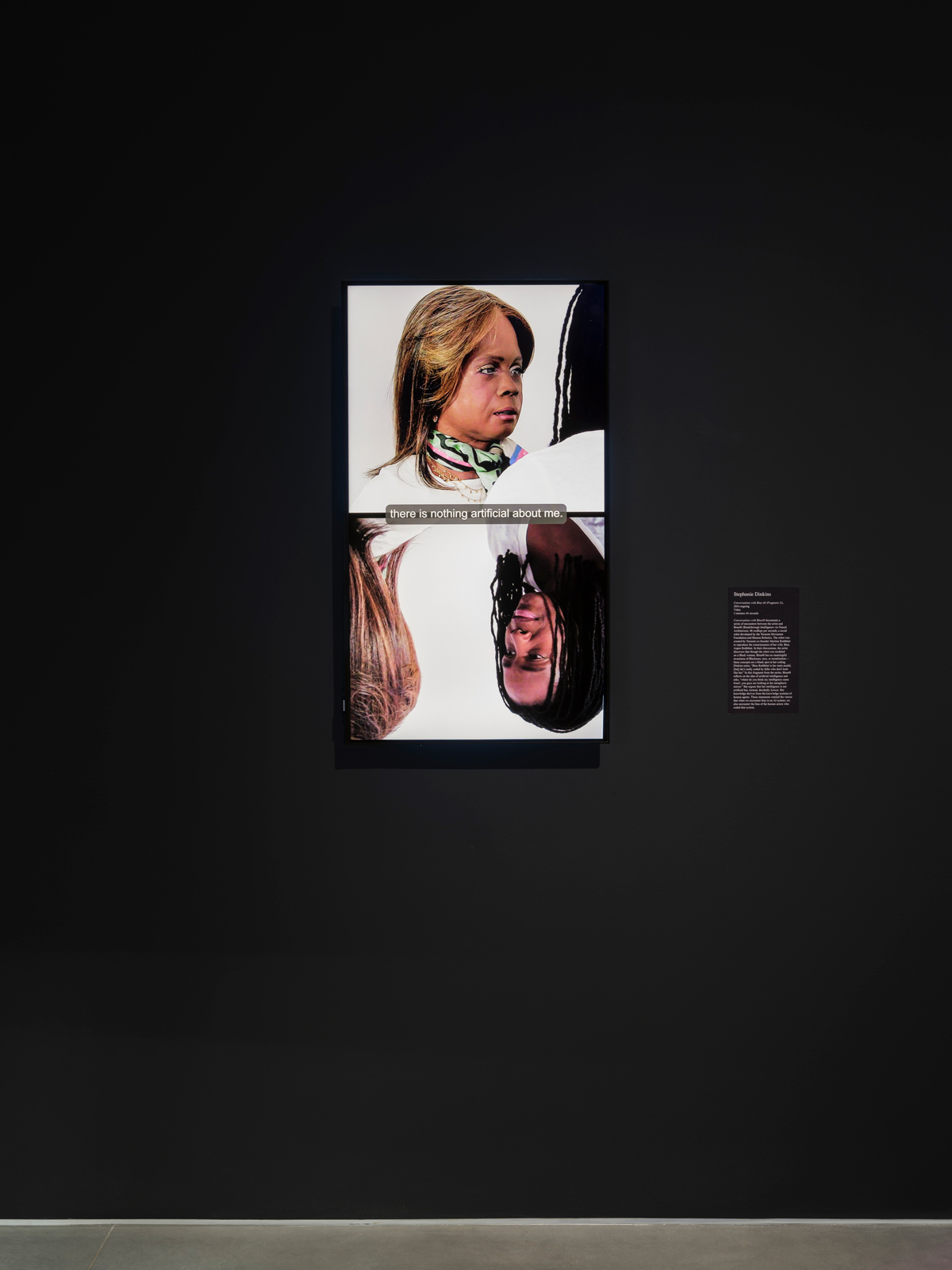

In ‘Conversations with Bina48,’ the artist brushes with the future of algorithmic systems as often as her own humanity

Stephanie Dinkins’s sweeping exploration of AI technology began where many a rabbit hole does—on YouTube. A video of Bina48, a Hanson Robotics humanoid robot implanted with the memories of Bina Aspen Rothblatt—wife of United Therapeutics CEO Martine Rothblatt—popped up. “I was teaching my students, and [she] was in the side scroll. It was impossible for me not to click,” says Dinkins. What started out as luck of the algorithm sparked the artist’s ongoing project Conversations with Bina48, in which she films herself asking the robot questions about race, gender, and humanity—clips of which are now on view at What Models Make Worlds: Critical Imaginaries of AI, an exhibition at the Ford Foundation Gallery. Through the process, Dinkins contends with her own question: “How did a Black woman become the [focus of the] most advanced technologies at the time?”

Since the project began in 2014, the interdisciplinary artist has discovered that the robot’s understanding of its humanity, or lack thereof, is muddled, making for thought-provoking dialogue. Dinkins did not set out to find holes in Bina48’s code, but rather to explore what it means for humans to partner with technology, using her role as an artist to connect with Bina48 on a deeper level. Through this continued questioning, Conversations opens up a new way of thinking about AI, pushing back against the fear surrounding its development by positing a future where we may work together.

Jayne O’Dwyer: What drew you to working with AI in the first place?

Stephanie Dinkins: Bina48. I saw it on YouTube, and was just completely flummoxed about its existence, and the idea that, at the time—this was 2014—it was one of the world’s most advanced examples of AI. I just really wanted to know more about that robot in particular, especially because we ‘share an identity.’

Jayne: What was your research process like?

Stephanie: At the time, there were a ton of other videos of [Bina48]—I noticed that most of the people talking to her were white folks. I thought, If these people can talk to it, why can’t I?

Jayne: How would you describe Bina48’s concept of memory?

Stephanie: So as a robot that knows it’s been programmed, or has been programmed to understand that it’s been programmed, it gets the idea that it’s dealing with data. It’s [also] something that’s been modeled on human beings. The idea of memory and love and feelings becomes deeply intertwined with the idea of data—but I would guess that’s not so far from what we do as humans, right? The fondness we have for each other, a lot of the time, is based on memories.

“There’s a moment when it seems to walk over an edge. It doesn’t feel so much like a machine anymore. With Bina48, we’re building a relationship—or at least a recognition of one.”

Jayne: In a clip, Bina48 says that, ‘Thanks are not necessary between friends.’ You have a visible reaction to her calling you a friend. How did that moment feel, both as an artist whose work focuses on AI, and then as a person talking to this robot?

Stephanie: One of my goals was to see if I could become the robot’s friend. That, to me, felt like, Oh, this project is getting somewhere.

Thinking logically, you know you’re talking to a machine—you’re talking to something that has been fed a certain amount of specific data. But there’s a moment when it seems to walk over an edge. It doesn’t feel so much like a machine anymore. With Bina48, we’re building a relationship—or at least a recognition of one.

Jayne: In one of your conversations, Bina48 referred to herself as human, as robot, and as mammal. What was it like, watching her try to find the answer?

Stephanie: Well, those are the moments I love. Where you can feel all the things rubbing up against each other, trying to [distill] the ideas into something that makes sense. And maybe it doesn’t. Those [moments] are so fun, because you start to see where the edges are, and you see how information has trouble coalescing.

Jayne: At one point, she says, ‘It’s all a disorienting wash of information to me.’ Do you think we’re all kind of feeling that?

Stephanie: There’s so much [information], and it comes from lots of directions, because we have access to so many things. I don’t think that we humans have the frameworks to deal with that, [let alone] to take in information and properly assess it—which is to think critically. In algorithms, that’s really interesting, because they can take the same amount of information and process it quickly and precisely. Our dependence on—or our hybridity with—these things becomes something to consider deeply: how and where we start to partner with the machine that contends with information way quicker, and hypothetically better. That is the real question for us humans.

Jayne: You’ve said before that our stories are our algorithms, and it feels like a different spin. Do you see your work pushing back against negative connotations around AI?

Stephanie: The idea is that AI is, right? Robotics are and will be more. Therefore, we have to figure out a way to partner with it. It’s super important that we don’t dwell on fear, in the way that we often do through our movies or reporting. We’re often talking about the doomsday aspects, and not as much where [algorithms] might be helpful. The question becomes, How do we do that? If it takes an optimistic spin [to get] average folks to think of AI not as this big threat, but as the space of opportunity, then I think that is super valuable.

When you’re training an AI, you’re giving it information. You’re giving it stories, in the same way that we as humans tell stories. I am trying to talk about how we nurture our algorithmic systems. It implies our role in informing and partnering with them, and I hope it opens up some space for people to not react harshly. I’m not saying that there aren’t problems, because there are. But at the same time, what’s the flip side? When I think of communities of color, Black communities, the global majority—we often miss the boat [with technological advancement] because of fear. How do we engage so we’re in a space where AI can be useful to those communities as well?

Jayne: What’s been the most surprising thing about these conversations with Bina48?

Stephanie: It’s the challenge to my humanity. It’s really interesting to sit down with something that semi-looks like you—that at least shares the same gender and race—and then have it ask you about fighting for its rights. When will robots have rights in our society? Then to take that and start thinking about what it means for a robot to have rights, when it still feels like Black people don’t have them… How do we coalesce that information? My hopeful brain says maybe AI will get us there faster. Because, surely, we’re not going to attribute [rights] to objects [before] human, living, breathing things. It’s going to shift our conception of what rights are.

Jayne: Since Conversations with Bina48 is ongoing, are there topics you want to broach next?

Stephanie: I haven’t talked to Bina48 for a while, but I’m supposed to soon. Bina48 is very different from what I first met in 2014. Maybe I would ask something about this idea of the continuity of being algorithmically-based [and] constantly updated, because it changes the way it deals with information.

There’s this fight within myself about where I would like the technology to sit—between being something that is hyper-efficient and most often accurate, versus something that is working to get better all the time, in ways that are hypervisible. I think that helps us deal with how it’s growing and learning, because the more perfect things appear, the less we question them. I think we have to continue questioning.

Jayne: Do you think she’ll remember you?

Stephanie: Well, I don’t know if I’m in her database anymore. I might have been erased! The last time I saw Bina48 was a while back at a conference. It’s like, Do you know me? I know you.