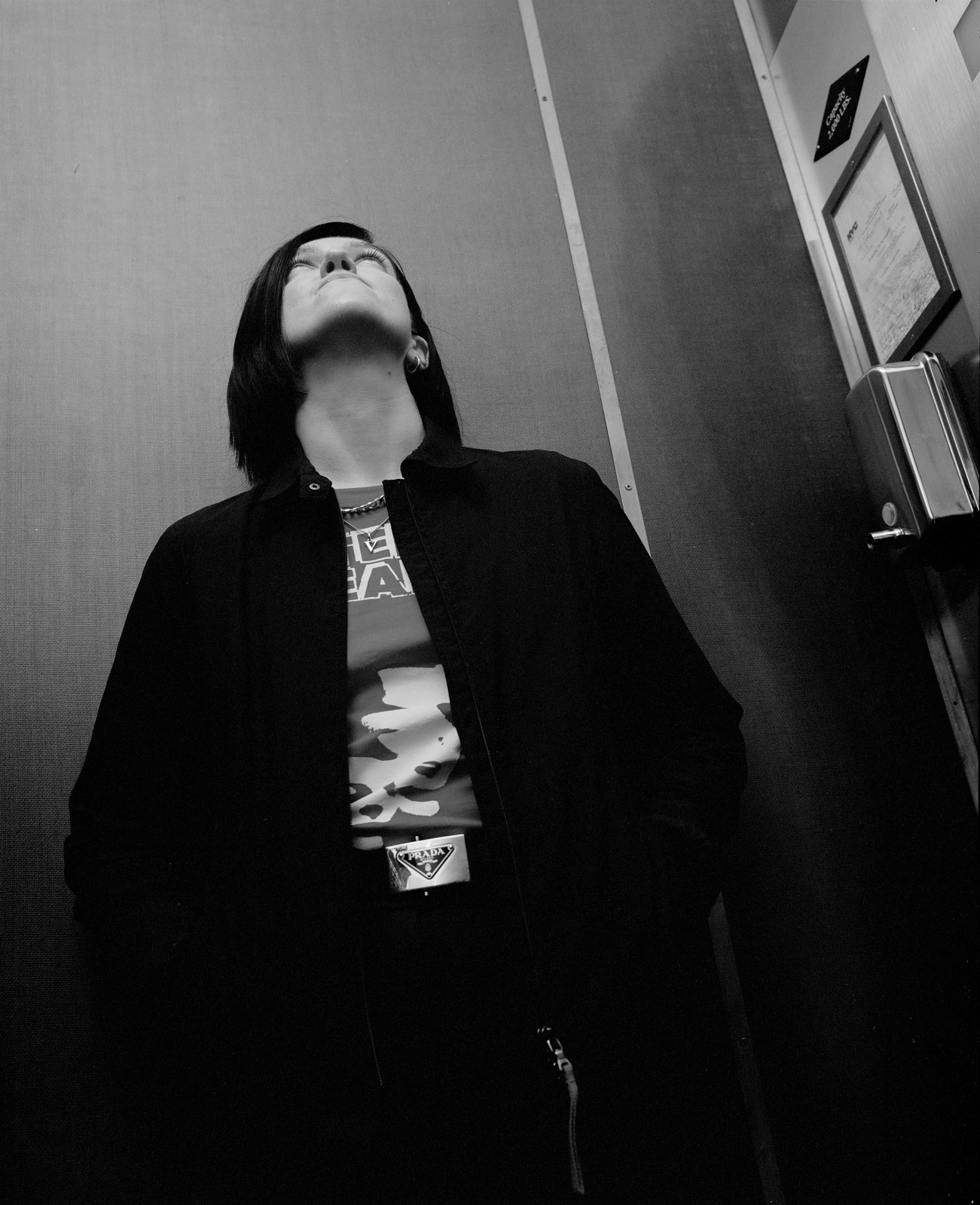

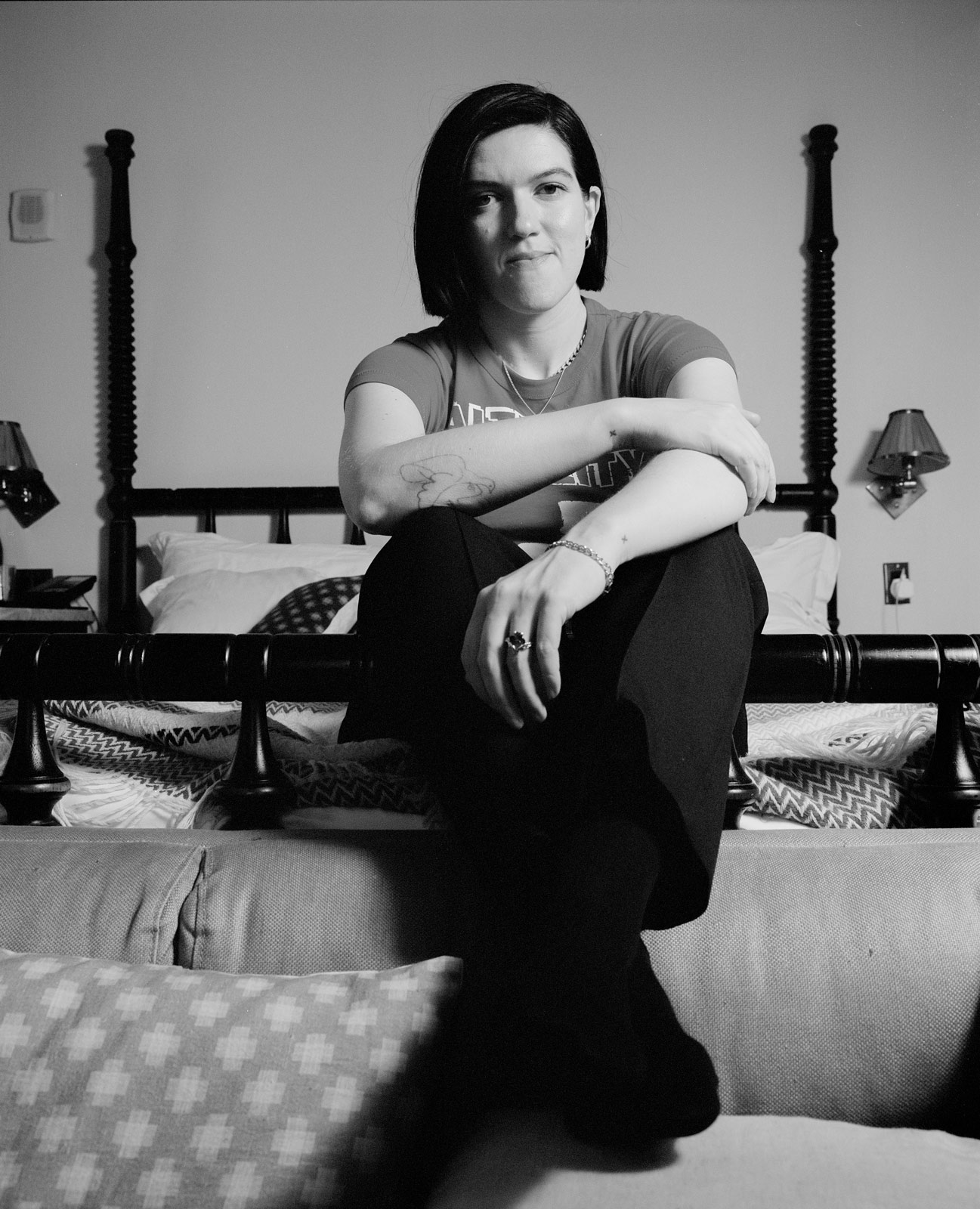

The two meet to unravel the act of art-making, comparing the musician’s solo debut against the filmmaker’s first feature

It may be an exaggeration to say that Aftersun would not exist without Romy Madley Croft, but it’s not an entirely baseless claim. She was, unknowingly, an early investor in Charlotte Wells’s career. In 2014, the filmmaker—a devout fan of Madley Croft’s band, The xx—received a perfectly-timed Facebook alert, notifying her that they’d be performing at New York’s Park Avenue Armory. Wells secured four tickets across two nights. She opted to attend one show, and sell the other set at an enormously marked-up price. “I feel really bad about that,” she admits to Madley Croft, “however, I spent the money on a video camera.” She used it to teach herself to make movies.

Fast-forward to 2022: Madley Croft’s team is in the audience at the Cannes premiere of Wells’s first feature film, Aftersun, following which, the two connected. The admiration quickly became mutual, culminating in an ongoing conversation on works in progress and ruminations on life. Their friendship was one with star-aligned timing—perhaps because Wells was actually situating the stars into place. The musician’s inaugural solo record (released under her forename) was in the works when the filmmaker’s first feature premiered.

On the surface, Madley Croft’s Mid Air and Wells’s Aftersun are wildly different: the former, emphatic, beat-heavy, and built for a club; the latter, softer-spoken, its subtlety packing its punch. But they’re also the same in some ways: inducive of catharsis, intimate and accessible, the grief they carry inextricable from the joy they embody.

Following their respective debuts, the two met to muse on the act of art-making—as both fans and friends of one another.

Charlotte Wells: When you shared a few tracks from your album with me, it was the most exciting thing. But also kind of terrifying. Because, do you really want to meet people whose work you deeply respect and admire?

Romy Madley Croft: [Laughs] Yeah, what if I was secretly horrible?

When I got sent the link to watch Aftersun, we had a Zoom booked literally right after I watched it. Like, the tears were still on my face, and then suddenly, we were just talking. It’s not very often that happens with something that moves you—to [immediately] be able to say how you felt about it, and dissect it with the person who made it.

Charlotte: I was thinking, What a nightmare to have to immediately articulate your thoughts. But it’s maybe easier to do it immediately than to have time to overthink.

Romy: It was a lovely way to first properly talk [to each other]—to go straight into a deep conversation before being like, ‘Who are you?’

Charlotte: It brought forward these parallels between filmmaking and music that I hadn’t considered before: the fine-tuning.

Romy: The whole question of, When is it done? I had a strong idea of what I wanted to do on [Mid Air], then halfway through, had some self-doubt, went in a different direction, and then realized my initial intention was the right one. But that’s the only way that you can feel confident when it goes out into the world—trying everything.

Charlotte: I’m not able to finish something unless I know the answer to all the questions. But then, the difference between film and music is I don’t ever have to watch the film again. I’ve seen [Aftersun] three times in the cinema—including its premiere, when it wasn’t finished yet. But with music, you [continue to] perform it, and you still have the ability to change it—it’s a different relationship to the finished work.

Romy: There were only two times you’ve watched it fully—no changes, end-product, done?

Charlotte: The first time, I said, ‘I’m dying, I’m dying, I’m dying, I’m dying. I’m dying,’ for 90 minutes. It was the opening of the Edinburgh Film Festival, I had 50 friends and family in attendance, and gave this emotional speech. I dedicated the screening to this teacher from high school who had been important [to me] after my dad died. I was just worried I’d screwed up the speech the whole time. The second time, I was at Telluride. A bit of time passed, so I was able to sit back and just let it go.

I had to go to this event this week where I gave a commentary on a short film from 2017. I watched that, and it’s like it could have been made by somebody else. That is the feeling I aspire to—detachment. But it takes time.

“That’s the only way that you can feel confident when it goes out into the world—trying everything.”

Romy: I have that when I listen to old songs—where it feels like it’s made by someone else, in a lovely way.

And I love hearing what the music means to people, once it’s out of my head. Because they’ve been listening to the music, they feel close to me, so it’s a direct deep dive into what the song means to them, what they’re feeling. They don’t really need to ask me anything—and I’d actually rather hear what they think.

Charlotte: I think I started working on [Aftersun] to force myself to ask questions, and to look in places that I’d never been willing to look. And then it gets to a point where you realize somebody paid a lot of money to make this film. And it’s not for me anymore, it’s for an audience.

The film is very subtle, as my work always is. And that leads to people interpreting it in different ways. The one thing I didn’t want to shy away from was grief. It felt really important to be open about that. At the same time, I’ve had a hard time figuring out where the lines are speaking publicly about my life, because I’m innately private, and, ideally, completely invisible—I don’t like my mom talking about me to her friends.

Romy: What I felt so moved by in Aftersun was a relationship between a father and a daughter that represented what my relationship with my dad was like—especially after my mom died. And it was just the two of us in scenarios where he was struggling mentally. Watching the film, you helped me empathize with my dad in a way that I hadn’t been able to yet. It was a gift to be able to connect with a memory that I had disconnected from, or hadn’t seen from an adult perspective.

Charlotte: That’s part of why I am relatively guarded, talking about myself—I let so much out in the film. I don’t believe in censoring yourself or your emotions in creating art. And sometimes, I wish the art could just speak for itself, because you’ve given everything. What more could you possibly have to give?

And I think it’s hard, when making something, not to get sucked into the idea that it’s for everybody. Nothing is for everybody. The more that it’s really for the people that it’s for, the better.

Romy: I struggle with that, because I’m obsessed with trying to make something universal—with writing something that’s deeply personal to me, but also relatable to everyone. I think that a lot of the music in The xx was ambiguous—we wanted to be. But on this album, I [wanted] to be more specific, as personal as I could. And it can then be interpreted in different ways, [which] is a beautiful surprise. Like, ‘Loveher,’ for me, is a lesbian love song. But people who aren’t lesbians are embracing it. There was this one video someone posted with it of their dog, and they’re like, ‘I love my dog. I love her.’ It’s surreal, these ways music can mean different things to different people. I want to celebrate that. But, if it can mean a lot to someone that it’s supposed to be for, that is really special for me.

Charlotte: It’s that thing: Universality comes from being as specific as possible to your own experience.

“I’m obsessed with trying to make something universal—with writing something that’s deeply personal to me, but also relatable to everyone.”

Romy: When I think about moments of shock and grief I’ve experienced, it’s this deep sadness, and then this deep clarity and rush of, I want to make the most of it. It’s the desire to make the best of things. There’s a line that I got from Beverly Glenn Copeland: ‘My mother says to me, Enjoy your life.’ That was my intention.

Charlotte: With film, it’s really hard to watch something for two hours that is relentlessly any one thing. I think you can pull off something very singular and sad in a song.

Romy: I was excited to try and make something really upbeat and joyful, and still explore emotional things. I think it would have been a lot quicker for me to make a guitar ballad album. But I don’t think I would have challenged myself. Staying quite a lot in that emotion is intense. I’ve been working on piano and guitar versions of this album, like as a part two. And I listened back to it. I actually found it too intense.

Charlotte: Without the joy, grief doesn’t have context. We feel loss because we had something. I think I definitely have a tendency to go down, and my cinematographer Greg was relentlessly pushing me to find the joy in moments. And, actually, if I could have done anything different with the film, it would have been shooting more moments of euphoric joy. In post, people said at various points, ‘Cut this scene, you don’t need it.’ And I was like, ‘This is the only scene where you see both of them smile.’ If you don’t see them goofy and warm and loving, what is she grieving?

I see people derailed by feedback before they know what it is they’re working on. But the feedback that I disagreed with the most was the most helpful, because it clarified my own intentions.

“Without the joy, grief doesn’t have context. We feel loss because we had something.”

Romy: I played some early music to my aunties, who are my mother figures, and they were like, What is this boom, boom, boom?

Charlotte: Family is the most humbling.

Romy: I really wanted my family to like what I was doing. And I realized that, maybe, it wasn’t necessarily for them. They loved the music The xx made, and I wanted them to have that connection with this project. I kind of got in my head about it. And then eventually, I tried to let it go. Then I spoke to one of my aunties the other day, and she goes, ‘My favorite song from the album is ‘Did I’.’ And I was like, ‘That song is literally the most boom boom boom on the album!’ I almost didn’t follow my instinct, because I wanted to appease the people I care the most about. And in the end, the most extreme version of what [they resisted] is that person’s favorite song.

Charlotte: It’s a tricky lesson, but sometimes you need to discount the feedback of the people closest to you.

Romy: I realize I get excited about an idea, and share it very quickly. I would share things [for this album] a lot with my wife. But a lot of his music is about her. So I’d be like, ‘I made this thing. What do you think?’ And then she’s like, ‘Is that really how you feel about me?’ I’m like, ‘Oh, yeah. But do you like the song?’

I think I gravitate to people that challenge me. I try to see my idea through a bit before [sharing it], because, like you said, I don’t [want to] get derailed.

Charlotte: It’s hard. I have that instinct to share really early, too. I’ll have an idea I’m really excited about that occurs to me at 11 a.m., and I tell people by 11:20. I know people who just don’t share anything. And then it’s like, ‘I published a book last week.’ I really wish I didn’t have that impulse. But it’s really hard. It’s lonely.

Romy: Creating is lonely. But then I think, What am I wanting from this? Why am I doing that? What am I trying to get from it? And can I give it to myself?

Charlotte: That’s a really good question to ask yourself. Sounds healthy.

Romy: I’m gonna try that a bit. But I just want to connect with people.

“Sometimes you need to discount the feedback of the people closest to you.”

Charlotte: Do you emotionally exhaust yourself?

Romy: I’ve still only performed these new songs live about six times. But I was playing at Coachella, and there was a moment where I really didn’t know how this game was gonna go. And I looked at the people [in the audience], and I just felt grateful. I kind of choked up. I was like, I’m not going to cry on the mic. And I thought to myself afterward, That’s not the point of the song. I’m contradicting myself. That’s the true me coming up, being like, Hold it in, and then I’m standing strong.

Charlotte: I approached a musician at a show once, and he was like, ‘I was up there singing the song, and I was thinking, Did I move my laundry from the washer to the dryer? And I remember thinking, That’s something I never wanted to hear.

Romy: I don’t know if I should tell you about that, then…

Charlotte: No, I mean—I get it. Especially when you’re on tour, performing night after night. But the illusion of connection was just shattered.

Romy: I think you get in a flow state.

Charlotte: Meanwhile, there are people in the audience having monumental epiphanies about their lives. At points, I do feel totally disconnected emotionally from my work. But [knowing] it started from somewhere real, somewhere meaningful—so long as that is true, the rest doesn’t really matter.

Romy: It is so funny, though, going to a gig, getting inspired by someone, writing down their lyrics—and they’re probably thinking about their laundry.

At the same time, I’ll be singing my heart out, and someone’s just yawning in the front row. And they don’t know that I can see it, but I can see it.

Charlotte: One of the most horrifying things I’ve ever seen in an audience member was actually at an xx show. Somebody in front of me was watching YouTube videos of the band during the concert.

Romy: Watching videos of a band play while at the show?

Charlotte: Yeah. The person I was with threw ice at them.

Romy: That’s amazing.

Charlotte: I think about it often… Why would you do that?

Romy: That’s also like someone talking to you whilst Googling you. Like, could we just be nice to each other without you knowing anything about what I’ve done in my life?