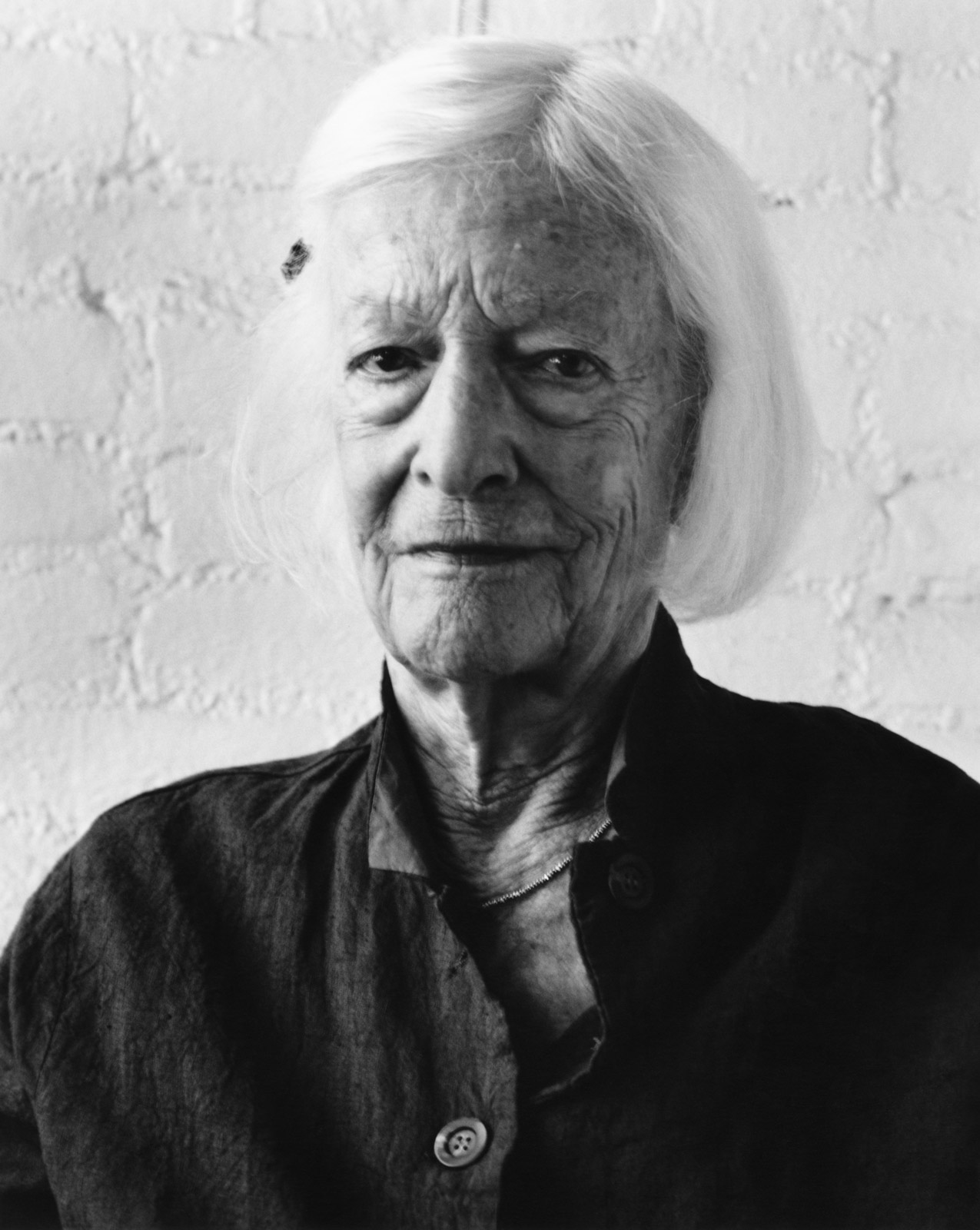

The artist joins curator Daisy Desrosiers for Document’s Fall/Winter 2023 issue, revisiting her metamorphic archive of performance

Listen to this article. Audio recording by Dossiers.

In a 2020 performance of Moving Off the Land, staged at the Museo Nacional del Prado, Joan Jonas swims with seals. The artist appears before the audience in the flesh while the seals glide on-screen behind her. They are more than just a passive backdrop. ‘When Jonas reaches out as if to stroke a writhing mammal, it yields to her touch and slithers away. Her arms extend—the seal projected across her back—as if the two bodies, present and virtual, are coextensive.

This interplay—between there and not-there—often crops up in Jonas’s pioneering oeuvre: spanning performance, video, installation, drawing, and text. Since the ’60s, she has playfully disrupted the directness of audience perception—anatomizing and multiplying her body with mirrors, masks, and cinematographic sleights of hand. Her performance Mirage, an ongoing project born in the ’70s, features chalk drawings on a blackboard, repeatedly scrawled and then erased. It’s been frequently restaged and adapted to new contexts—a practice not uncommon to her work. Jonas’s art is an affront to stability: an insistence always on seeing anew, doing again, and questioning everything.

Perhaps these fascinations—magical collapses of space, time, and materiality—began for Jonas in childhood, attending magic shows and operas in New York in the ’40s, and cultivating a deep interest in folklore. She began her career as a sculptor, a medium that feels too sturdy, too absolute against the ways her practice has embraced the fluid, exploratory, and malleable. She never let its permanence take hold. After withdrawing from sculpture in the late-’60s, Jonas destroyed all of her work. Her sensibilities were then molded in the crucible of the avant-garde New York art scene, under the influence of choreographers like Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown, and at the unprecedented intersection of different media.

With the advent of video and performance art, the body was more a part of Jonas’s work than ever, bringing with it a new challenge: How does an artist convey their work without recourse to traditional modes of figuration? Their role is one of a translator, a task that brings the impossibility of perfect replication. Though some elements may get lost, others might emerge.

Translation, at least, is one way in which curator Daisy Desrosiers describes Jonas’s work. The pair first met at an exhibition in Milan in 2016 and have remained in close dialogue ever since. Their friendship is built around shared fascinations with literature, place, and nature—recurrent themes in both of their personal lives. Since Desrosiers became the Director and Chief Curator of Gund Gallery at Kenyon College in 2021, her bond with Jonas has been a touchpoint for thinking about the relationship between artists and galleries, and by extension, the practice of curation.

In this way, friendship emerges as a mode of creativity. In the ongoing archive of Desrosiers and Jonas’s conversations, new ideas emerge that nourish their work and lives, to which they circle back repeatedly, continuously revising and drawing out threads to pursue headfirst.

Most recently, Desrosiers and Jonas have been revisiting the scope of the latter’s career, considering what it means to return to the archive while also looking ahead. They look back to people and places that have driven them forward to the major retrospective of Jonas’s work—the largest ever in a US museum—to be held at MoMA in the spring. To approach the whole of Jonas is an impossible task. It’s not easily slotted into static moments from the past. Instead, the retrospective leans into what is undeniably alive about her work: a constant state of reanimation and curiosity.

As Desrosiers, in Ohio, calls Jonas, in New York, the pair’s discussion embodies this ever-shifting dynamic—the making of space for exploration and change that fuels great art.

Daisy Desrosiers: In my new role, [curiosity] is a big part of how I’ve been exploring the possibilities of change, of exploration. How do we reimagine the way we tell the stories? You and I have talked on a few occasions about some of the prompts that guide your thought process, for example, the intricacies of ideas into forms, and the intricacies of translating one to the other.

Joan Jonas: When it comes to translation, I always [say] in relation—from one form to another. That’s one form of translation, and then working with others and with literature and nature…

Daisy: What’s interesting to me, with translation, is that it can be a negotiation between tensions and forms, and sometimes, a no man’s land. As a French speaker working in an English-speaking environment, I think a lot about what is left in-between—[like Emily Apter’s idea of] the untranslatable. This is also the interesting potential of the translation process: what we learn about the transfer of one form into another.

In your work, translation also exists in relation to citation, writing, or the formation of new visual language. And you’re working on a huge retrospective at MoMA. The last time we saw each other, we looked at the maquettes with curator Ana Janevski and the production team. What does it mean to revisit such a wide practice?

“When it comes to translation, I always [say] in relation—from one form to another.”

Joan: I had a show that had some of the same works at the Tate in London, and then again, at Haus der Kunst in Munich, so it’s not a completely new experience. But [over] all these years, I’ve shown much more in Europe than in America. I’m so thrilled to be showing the work in New York—my town. I always wanted to be able to bring it here. [I’m curious to see] how people will interpret it. I’m also curious about my perception of the work in this new context.

Daisy: This idea of exploration and leading with curiosity, with questions is part of how I would describe your process. One of the things that has always moved me is that you want to engage a new generation of artists. You pay such close attention to what is emerging, what is being processed by the vanguard. You’ve also collaborated with practitioners who are not only visual artists but who come from the sciences or music, with deep investments in each of these disciplines. I also see [our] conversations as a kind of ongoing collaboration, like a shared hard drive that we’re building together. Can you reflect on how the role of collaboration in your practice evolved? And your thoughts about an intergenerational setup, because I really see it as an equal mode of exchange for you. There’s something here that feels so Joan Jonas.

Joan: One of the reasons I work in performance is because I really like working with other people. Until I worked with [jazz musician] Jason Moran, it took me a while to accept the idea of a collaboration, because I thought if I did the piece and Jason did the music, that was what it [would be]. But if I look at it from an audience’s point of view, they don’t see that separation. They see the two things together, imprinting on each other, and they experience them as one. It took me a long time to realize that.

Daisy: You have to reckon with that split, that moment of dissociation. How has that informed [your] recent work and the community that you bring along?

Joan: The way Jason and I worked together was [that] I got everything all worked out except for the movement. I had the text, words, video, backdrops all figured out. And then, we were given six weeks to work in the space [at Dia Beacon], which neither of us ever had before—it was an amazing luxury. We went there every day for six weeks. We would take each section and I would play the video and listen to the music that he had come up with. My movements came from responding to his music. It was two separate threads that became intertwined.

Daisy: What you’re describing feels like a call and response, right? Where you’re each putting something forward, and the other is responding or you’re responding together. But by sharing space and inviting new conditions to engage with the material.

Joan: I love that you mentioned call and response because that’s a term used in music. When I worked with Eiko Otake, it started out as a real collaboration which I found difficult because we’d already worked together. This time we had two simultaneous performances. She spent the [previous] summer in Wyoming, and I had spent a summer in Wyoming when I was 14. I never would have told that story unless Eiko had brought it up. She was very good about responding to my baroque use of video; whereas hers is very minimal. She made curves the very color of a Wyoming landscape whereas mine had a lot of color.

So many things came out of me, because in my old age, I’ve become much more relaxed about entering another person’s world and combining our experiences.

Daisy: Joan, I think of you as fearless, and in listening to you, I feel you’re also saying it’s even more about the capacity to embrace new places [your] practice can go. We touched on your upcoming exhibition in New York but we should also talk about our connection to Canada. You spend a lot of time in Nova Scotia, in a very different environment [from New York]. Now that I’m based in a more rural environment, I’ve become attuned to how inhabiting different spaces can push your practice forward in ways you can’t always anticipate. I’d love to hear about your sense of place in both of these environments and what they prompt for you.

“In my old age, I’ve become much more relaxed about entering another person’s world and combining our experiences.”

Joan: Well, when I first responded to that culture in [Cape Breton], the old people were still speaking Gaelic. Having a French-Irish background, it spoke to me. I don’t think that way anymore, exactly, but that’s what drew me to that culture.

And then, just putting my camera outdoors and entering the world of nature and the beauty of it—it’s kind of a collaboration with the landscape. I owe so much to that place and people. Now it’s less cultural, I’m into other questions of interacting with others.

Daisy: You’ve been part of this place for a few years now. Certainly, that relationship, and maybe some of the distance that you evoke, or sense of proximity, has changed over time.

I also think about that when it comes to what a curatorial practice. And part of the term I used to explain it was very much along the lines of a translator—I really think about the curatorial role as one where you have access to so much information, and so part of what you do is distilling. I think about an exhibition as a sentence, and curation [as] choices in punctuation. You’re conveying what has been shared with you in the studio, or what you’ve registered as you get to know the practice better which requires that you leave things behind to move them into a different space.

There’s a quote from you that I thought was so beautiful: “The performer sees herself as a Medium: Information passes through.” If you think about the video and film work that you’ve done, the object-making, or performance—is that statement still one that guides your practice?

Joan: Well, I mean, I like the word “translation;” I’ve used that myself in relation to what I do when I make a performance, and then literally translate it into an installation—because you have to translate [to other mediums], you can’t just plop it in. The other question is performance, which in the very beginning, was kind of thought of as being transitory and ephemeral. And I always wanted to make something of it that was more concrete.

I think [translation] also has to do with my personal nature of always wanting to be somewhere else, be with another family. I explored other cultures, not as a scholar, but as a practitioner. I learned in relation to information passing through that comes from thinking about being a shaman. A shaman has information coming through the body, in different ways in different cultures. And so that was one of my big inspirations.

I don’t think of my work in that way now, but it’s in my body. If you study something and absorb it, at a certain point in your development, it just stays there. It’s part of the work. And it’s important to keep a connection to it.

Daisy: I think there’s something profound about what the body remembers as you’re going through motions. That is something that can only be recorded through that action, that gesture that will never be the same, but that can remain and be recorded in this way. It reminds me of the conversation we had over dinner about Maya Deren and Meshes of the Afternoon. I was sharing with you how my Caribbean heritage and my relationship with Haiti started through the lenses of artists, as I was not born there. Maya Deren spent a lot of time in Haiti studying voodoo, and paying close attention to rituals and the role of objects in them —how they can become animated or be given a function in the context of a performance.

Joan: I was deeply influenced by her work in Haiti. Before they edited her films, Anthology Film Archive showed the entire footage—like four hours of footage that she shot in Haiti—of people making these drawings on the ground with white chalk, and it profoundly influenced me as a ritual. In the final edit, they just show the drawing, and then they cut to another thing. But in the unedited [version], they draw over and over again, making these incredible labyrinthian images. I directly took that for Mirage to make the chalk drawings on the blackboard. They were my images, but it was inspired by those drawings.

From the very beginning, my work would come to me and I’d have to make a space and step into it, play a role or whatever—it comes to me through the body. I mean, that’s what dancers do. As a dancer, you can’t really put it in words, and you can’t really record it in images. It comes through the body, it’s a live experience. I think a lot of artists feel that, you know, where does this come from? We don’t know. It just comes to you. One of my pieces is called, They Come to Us Without a Word. I was talking about fish, but you know, it describes this a little bit.

“I think there’s something profound about what the body remembers as you’re going through motions.”

Daisy: Speaking of oceanic life, I wanted to talk a little bit more about your work with [scientist] David Gruber. How did you meet, and where is this collaboration leading you now?

Joan: I’m interested in perception: How do we perceive? And how does our perception change with different situations? David has developed cameras and lenses in order to see certain fluorescent fish, or sharks and turtles that are fluorescent. It’s a world we don’t know, which is also totally intriguing.

I put a lot of that work Moving Off the Land. And then when [it] was over, I didn’t want it to be! I also thought that David’s fantastic work should be shown, and not be in the background. He’s doing this project about whales in the Caribbean and I’m involved with that. It’s very complicated and emotionally disturbing, but the whales are amazing. It’s going to be in the MoMA, I hope.

Daisy: One of the things that I found most fascinating about whales is how they communicate with each other. And just imagining an entire system of communication that is unheard of for a human… If I let my imagination go wild, I think about all the conversations that are happening that, even if we wanted to listen, we couldn’t capture.

Thinking about these overwhelming sets of communication all around us, your work and your reflection on this ongoing relationship with David makes me think about the unknown in such an exciting way.

Joan: More and more people are thinking about how animals communicate. The human being is not the top of the pyramid. [David’s] project has to do with listening to sperm whales, and an attempt to understand what they’re saying to each other with this clicking noise.

I went to a conference yesterday, and somebody was looking for a word to describe it, and I think miraculous describes all of these situations. It is miraculous.

Hair and Make-up Erin Piper Herschleb using Oribe at L’Atelier NYC. Stylist Assistant Imaan Sayed.