In her biweekly column for Document, McKenzie Wark ponders the problem of art in the age of content

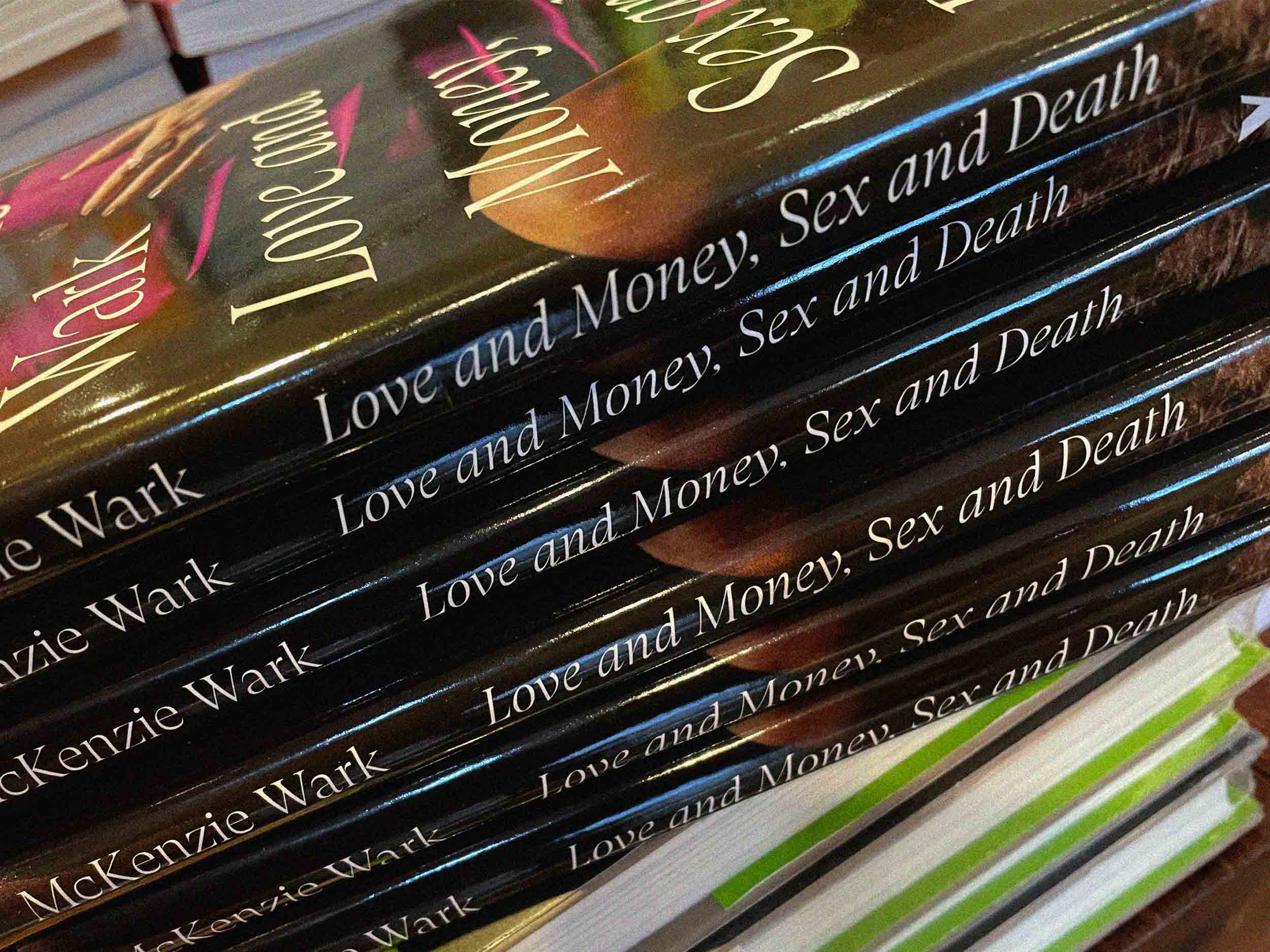

I was in Spoonbill Books on publication day, when copies of my new book, Love and Money, Sex and Death, arrived. Many came out of the box damaged by their travels. Seeing their poor, crumpled forms caused me physical pain. I had to look away.

It’s always a strange moment for me when the book becomes a real thing in the world—but this one hit differently. There’s always some of me in it, and there’s always something strange about seeing that extruded into an object made of ink and glue and paper. This book has rather more of me in it than usual, somehow. I’m more than usually sensitive about it.

Maybe it’s the aging, but these days I find old-fashioned things, like actual books, the most charming. There’s so much “content” I could access just from my phone, but I’d rather go into a bookstore and buy a good book. Something about the heft of it. The scent of the paper. Its feel. Something about it being an object in the world. One that so many people labored to bring into being.

I find that I just can’t watch television anymore. I stare at my laptop for much of the day at work, so I’d rather not look at it when at my leisure. I’d rather be dancing. Like reading an actual book, an actual dance floor still seems to have some of the charms of an actual culture. One not optimized by algorithms for the extraction of value.

I went to see the Wolfgang Tillmans show at David Zwirner not long ago, and had the pleasure of meeting Wolfgang there, in the company of Phong Bui, publisher of the Brooklyn Rail. Wolfgang pointed out a few things about the installation before we departed for our lunch reservation. The photographs might be made by digital means, but their sheer presence in the room, and the subtle dance of their arrangement in relation to each other and to the space, hit with intensity and clarity.

What counts, these days, as an aesthetic experience worth having? There’s just so much “content” everywhere, such a total saturation, that it gets hard to orient oneself toward any particular instance that might enliven the senses. All of it happens as some sort of business. My books are sold in bookstores. We’re hoping enough of them sell to at least justify its existence. The dance floor exists to attract enough people to buy drinks or pay a cover to keep the club going. An art gallery sells art as rare objects to collectors. It’s not like there’s an outside to art as commerce. How then to make distinctions within the culture industry between good and bad art?

It is not a critique of capitalism to be bad at business. On the other hand, the business of art has nothing to do with the quality of experience it might offer. I don’t think it’s helpful anymore to think of it as the culture industry. It’s been replaced by the vulture industry. Today’s information business picks over the corpse of culture. Scavenging for scraps of value to extract.

“Who is at least attempting to reverse the form of the commodity and reveal that other side—that art is always also a gift?”

It’s telling that it’s called “content” now. If you’re even passingly familiar with the principles of aesthetics, you’ll have heard of content in relation, always, to a second term—form. If the content is the specifics of the subject the work addresses, form is the way in which one chooses to express it. Form is shape, style, pattern, material.

Most things that are interesting in art will play with our preconceived ideas about form. Avant-gardes tend to go overboard with radical departures from it, on form’s destruction and reconstitution. Maybe it’s not always necessary to take such extreme measures. Form can be in play in more subtle ways, too. Exploring the variations of rhythm, shape, style, pattern, material. Making us gently, rather than savagely, aware that what we are engaging is a work of art, an artifice, an extrusion out of the necessities of the world into other possible ways of being.

To call it “content” rather gives the game away. Contemporary media wants us to forget questions of form. To take it for granted that the form of all media is now the kind of streaming vector that sits like a vulture on our capacity for attention. That all content has to do is turn attention into revenue, and that any kind of attention will do. The result is the repetition of sameness. The same music, the same shows, the same images, the same texts. Just with minimal variations. They might as well be made by machines.

Is it any surprise, then, that boredom is such a common reaction to the culture of the times? The vulture industries do their best to counteract it by increasing the intensity of the content they sell. And by increasing the hyperbole with which they sell it.

Maybe I’m just in my cranky Frankfurt School era. I used to have a little more hope that it was possible to signal through the noise. It is indeed the case that all of culture is infected by the form of the commodity, which renders it all the same. The form is always “product,” the content molded by that form.

It’s a reversible thought, perhaps. It’s always commodities we’re sold, but they can’t help also being cultural. Some residue of another art for another life swills about as sediment in the soda pop of popular art. Or so I always used to think.

If you’re an artist, you tend to know who the real ones are in your chosen form. Who is doing work that puts pressure on the form? Who is doing work that addresses its public as something more than a consumer? Who is at least attempting to reverse the form of the commodity and reveal that other side—that art is always also a gift? The gift of another kind of attention.

Well, I’ve tried. Particularly in the books I write. Although perhaps they always end up on the marketplace as damaged goods.