Following the release of ‘As It Was Give(n) to Me,’ the photographer joins Document to unravel the region she calls home

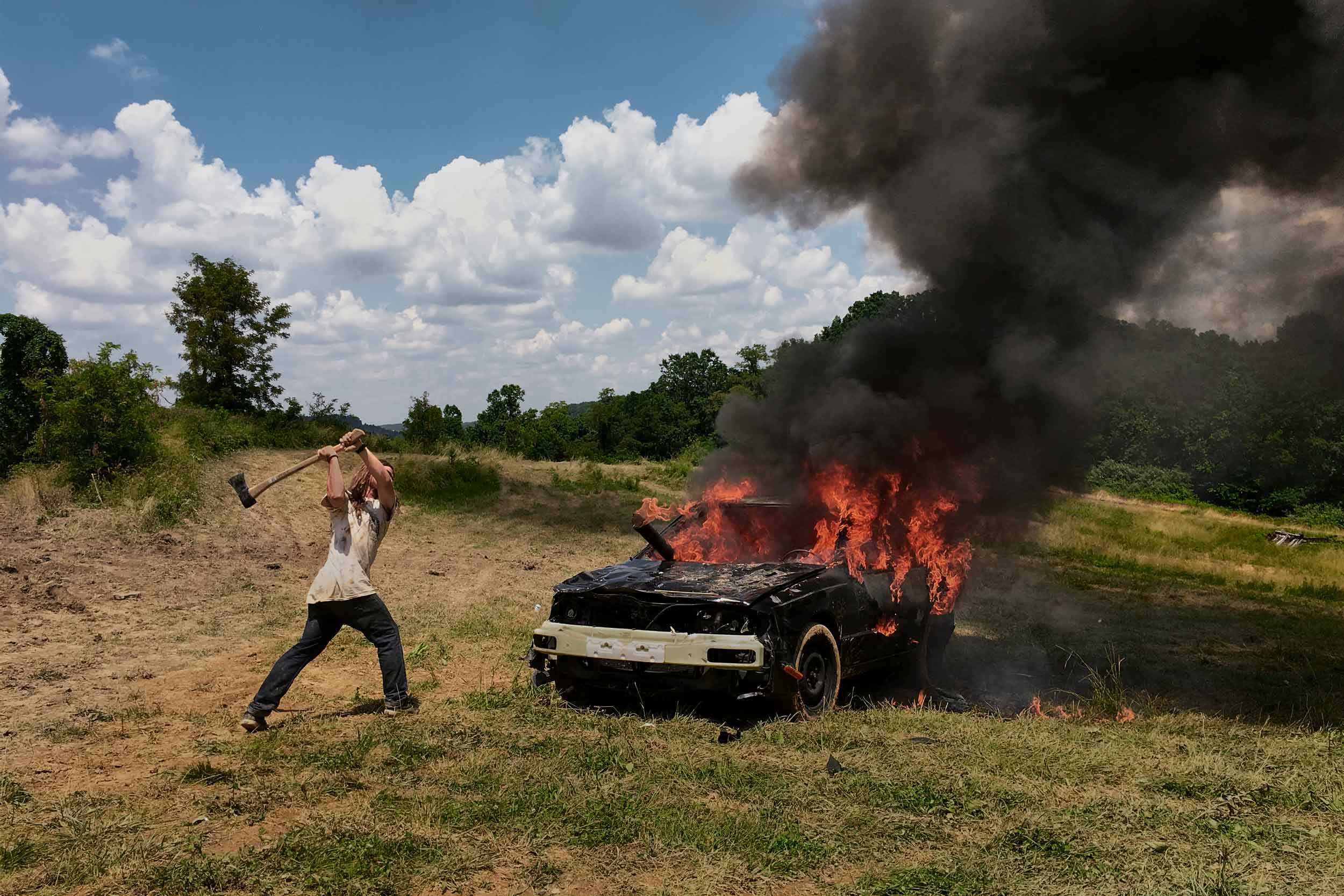

Stacy Kranitz knows being in front of the camera is uncomfortable; she doesn’t like it, either. A Kentucky native, the photographer now lives in the Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Tennessee, where for over 13 years she’s been taking portraits of the region’s residents—including herself—to create an arresting body of work titled As It Was Give(n) to Me. The series is an exercise in allowing; Kranitz understands that her intimate portraits cannot undo the years of misrepresentation baked into the world’s view of Appalachia—but she also knows that a photograph can hold multiple truths at once, the audience confronted with both their preconceptions and rebuttals of them, contained within a single frame.

As It Was Give(n) to Me continues Kranitz’s years-long examination of typically-neglected communities which exist outside the mainstream conception of American life. Citing Catherine Opie, Jim Goldberg, and Chris Verene as influences, she straddles the line that separates documentary from fine-art photography, seeking to represent her subjects exactly as they are.

Avery: How did you come to photography?

Stacy: I remember having a distinct impulse to document things, from the time I was 11 years old. I pretended to be Harriet the Spy, solving made-up crimes in my suburban neighborhood. At my high school, they had a darkroom. That was when I first started taking pictures.

“This is why I make the work I make: to have my ideas about things unravel.”

Avery: What did you photograph then?

Stacy: I was initially drawn to street photography. I was in New York and struggling with depression. On Friday and Saturday nights, I would leave my house on Ninth Street and walk to Times Square, before it was gentrified. There was still an element of danger. My favorite place was the Port Authority Bus Terminal. I would walk around and photograph other people, who looked lost in the world like me. It was this cathartic thing at a time when I was struggling.

After two years, I realized I wanted to actually talk with the people I photographed, and develop genuine, ongoing relationships. I interned with a non-profit that owned a single room occupancy hotel in Times Square. They paired me with a writer to [work on] an oral history project. We spent time with five residents who volunteered to let us into their lives. That was when I really started to see photography as a way of connecting deeply with people.

Avery: John Szarkowski had that famous show, Windows and Mirrors. After World War II, documentary photographers were [categorized as one of the two]: Windows photographed the world as it is, and mirrors used their creative impulse to demonstrate how they saw the world. Which group do you belong to?

Stacy: I guess I’m someone who shifts back and forth between the two. I’m interested in that space between the actual and the interpretive truth, where the window and the mirror devolve into one.

Avery: Your photographic subjects are sometimes forgotten or overlooked. How do you build trust with them, to establish access to their communities?

Stacy: I try to engage with people with a lot of vulnerability from the outset. I do not shy away from discussing difficult things, but see it as a given that I will put my foot in my mouth. I try to find ways to indicate I am interested in accepting people for who they are, instead of what I want them to be. I don’t come into people’s lives in a formal or composed fashion. I appear more like a disheveled mess, eager to share whatever struggles I am going through—and I hope that gives other people the space to do the same.

Avery: What is your research process like?

Stacy: When I am home, I allocate my afternoons to research and discovery. I dig through digitized online archives, read books, and watch films. Research upends what I think I know, and allows me to see and think about projects in new ways. I have stacks of books for each project all around my studio, so it’s easy to bump into one, pick it up, and get lost.

Avery: If you weren’t a photographer, what would you be?

Stacy: I tried to step away from photography and I couldn’t. It’s just a medium that suits my personality.

Avery: [Laughs] You tried!

Stacy: I know, deep down in the core of my being, that I cannot be anything else. This is a problem, because photography is an expensive medium, and there is not a lot of financial stability in doing it full-time. I started out wanting to be a filmmaker, but I realized very quickly that I suck at orchestrating large groups of people. When I started taking photography classes, I loved that I could dictate my vision to myself in my head.

Avery: You sometimes assume the character Christy, from Catherine Marshall’s 1967 novel of the same name. What can Christy do that Stacy can’t?

Stacy: When I was a child, I saw this miniseries about a young missionary who goes into the Appalachian Mountains to teach the poor people how to read and write. I was drawn to Christy’s clear sense of self—her need to understand things as either bad or good, and the ways that constantly failed her. I see the missionary as a corollary to the documentary photographer. Have you seen it?

Avery: I watched a brief clip.

Stacy: You haven’t watched the 900-minute series? [Laughs] Christy is based on the experiences of the writer Catherine Marshall’s mother. Both the missionary and the photojournalist assert a right and a wrong onto a group of people, through the guise of capitalist moralism. But as I was making my work, and starting to become a documentary photographer, I realized how fucked up that is. We no longer see missionaries as heroic. They are part of a legacy of colonialism.

By the end of the story, Christy becomes undone by the people around her in Appalachia. She learns that there are many versions of right and wrong. This part of the story is the most meaningful to me. Everything she thinks she knows is turned upside down as she develops deeper bonds with the mountain families. And this is why I make the work I make: to have my ideas about things unravel.

I’ve been fascinated with Christy for so long, but I realized that she portrays a narrow view of what a woman is. I started to think about other characters who embodied darker parts of me. A few years ago, I saw Barbara Loden’s film, Wanda. Loden is from the same mountains as Christy, but Wanda—who is based on a real woman named Alma Malone—speaks to a growing frustration about my place in the world. While traveling in Appalachia, I came across women who had been irreparably harmed by the world and are lost in a frail state of being. Christy is a do-gooder; she’s sure of herself and confident. That is not me, or many of the women I encounter while making my work. In some moments in my life, I have been barely able to put one foot in front of the other to climb out of the dark holes I found myself in. Wanda so heartbreakingly represents that to me. And so now, I am me, I am my mother, I am Christy, I am Barbra, I am Wanda, and I am Alma. I am a shape-shifting amalgamation of all of these women. I am fascinated by this idea of a woman telling her own story through another woman’s story—of taking my wound and placing it inside someone else’s.

“I try to find ways to indicate I am interested in accepting people for who they are, instead of what I want them to be.”

Avery: How does it feel to be in front of the camera?

Stacy: I don’t like it, but I do it because I have asked so many other people to do it. Some people take to being in front of the camera naturally, but a lot of people don’t, and I must work to make them comfortable. I use the same skills to make myself comfortable.

Avery: Where does photography start for you, and how do you know when you’re finished?

Stacy: The start happens without me realizing. As for the end—I don’t believe in exit strategies. I’m never finished with a project. It took me 12 years to make As It Was Give(n) to Me, and it feels like I am just beginning. What bothers me most about contemporary documentary work is the shallowness of it. So much lives on the surface of an idea, instead of being embedded in it.

Avery: What drew you to Appalachia?

Stacy: I came by accident. I was working on what would become From the Study on Post Pubescent Manhood, and I realized I was in Appalachia. A place known for representing poverty. I wanted to know what that meant. At the same time, I was looking to make a body of work that both critiqued and celebrated the documentary tradition. I had grown frustrated, working as an assignment photographer and photojournalist. What was most problematic to me was the fantasy of objectivity. And because objectivity is a fundamental, core principle of photojournalism, I found this thing that I had bought into dishonest. But I still loved it. Appalachia had been really harmed by photography, so it seemed like an ideal place to make work that commented on the failures of the documentary tradition. I kind of fell into the arms of Appalachia.