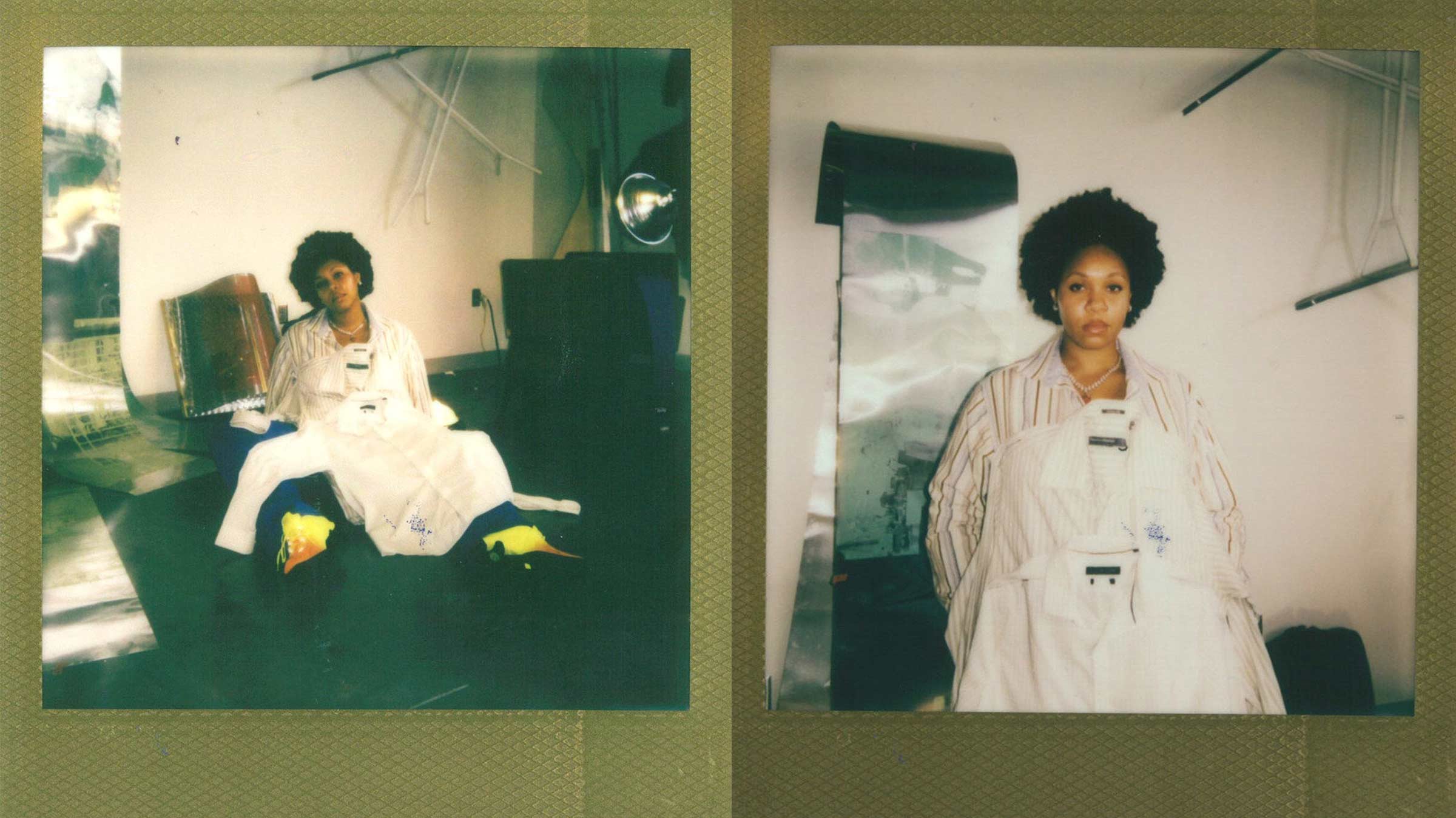

Cameron Patricia Downey speaks on their inaugural museum show in conversation with their former art teacher, painter Caroline Kent

Cameron Patricia Downey and Caroline Kent first crossed paths in a Minneapolis classroom—the former, a 14-year-old student and Northside native, the latter, a practicing painter and educator, instructing a cohort of young creatives for the arts nonprofit Juxtaposition. “[Those years] were really formative in my decision to pursue the arts,” Downey tells Kent around a decade later, in conversation for Document, “and also how to think about art in terms of what it means to have a concept, and stand beside it.”

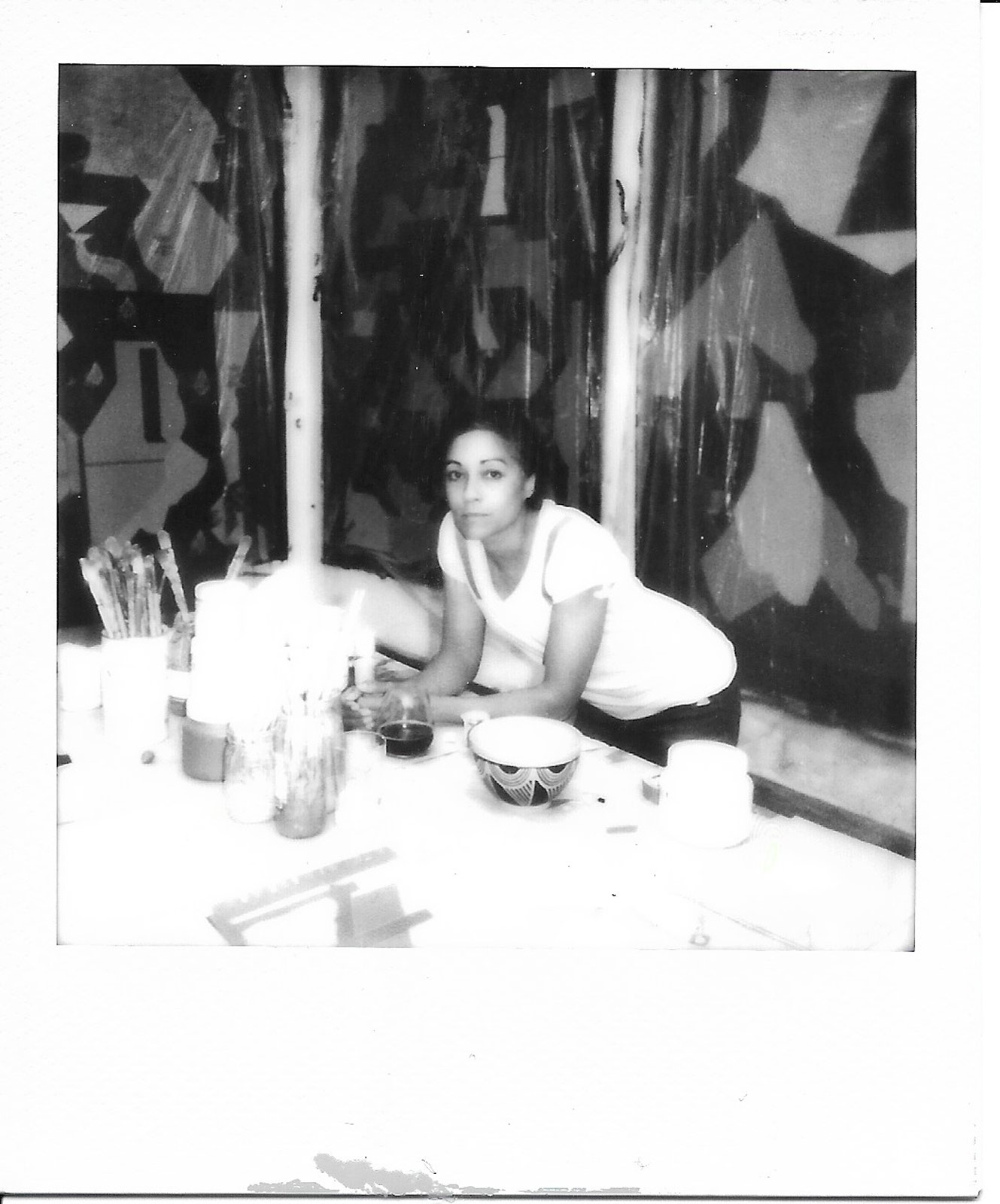

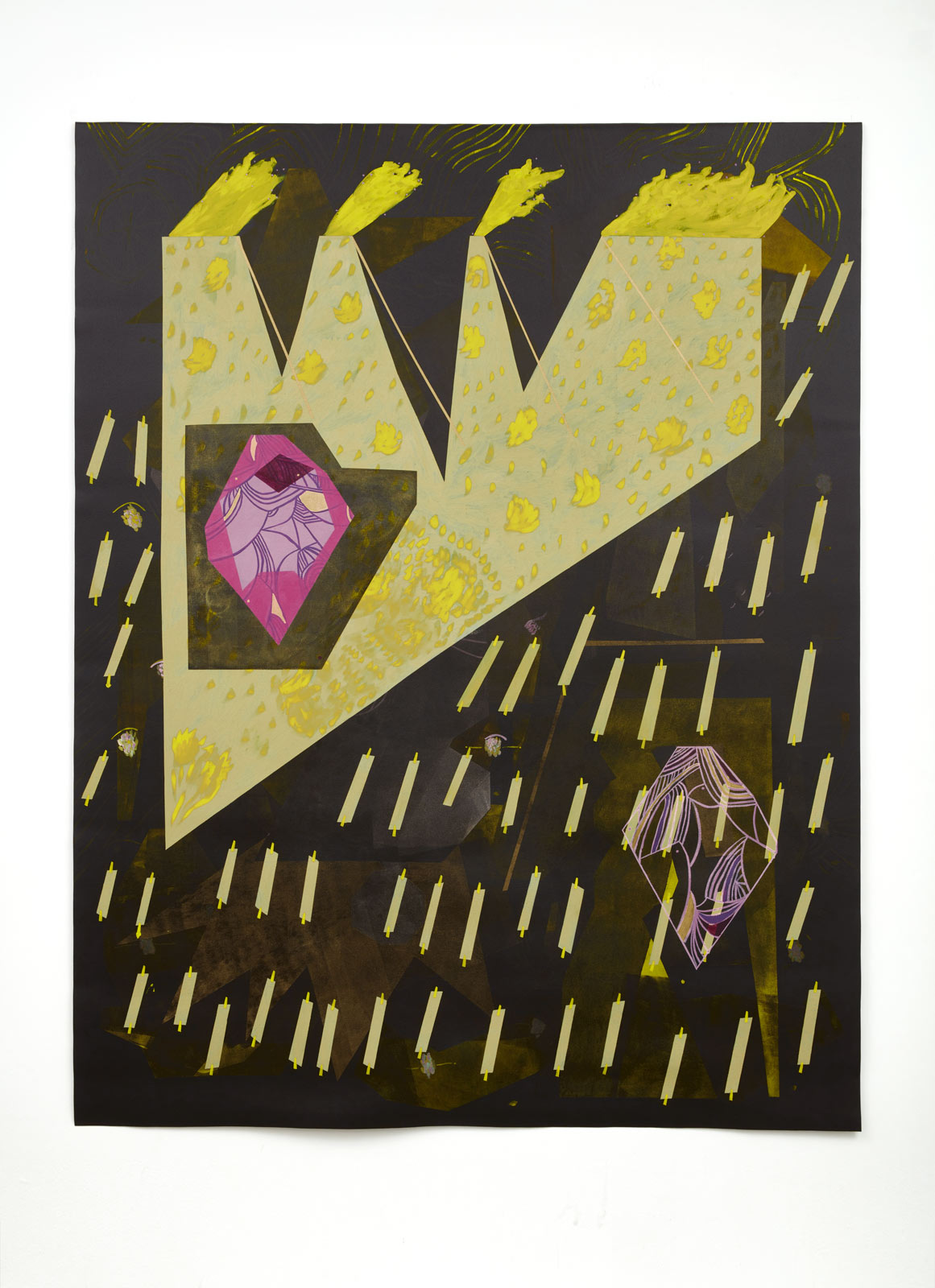

Kent—likewise a Midwesterner; Sterling-born, Chicago-based—recalls fostering a discursive environment. At Juxtaposition, if the lesson of the day was a still life, there was the understanding they’d be talking as they drew: about pop culture, about their city, about artists students liked and thought they might emulate. This sort of openness relates back to Kent’s work, exploring abstract geometry as its own form of language. Her paintings are conceived via trial-and-error: saturated, free-form shapes, thrown up on a dark background—evoking something that need not be defined, as the meaning-making journey is also the destination.

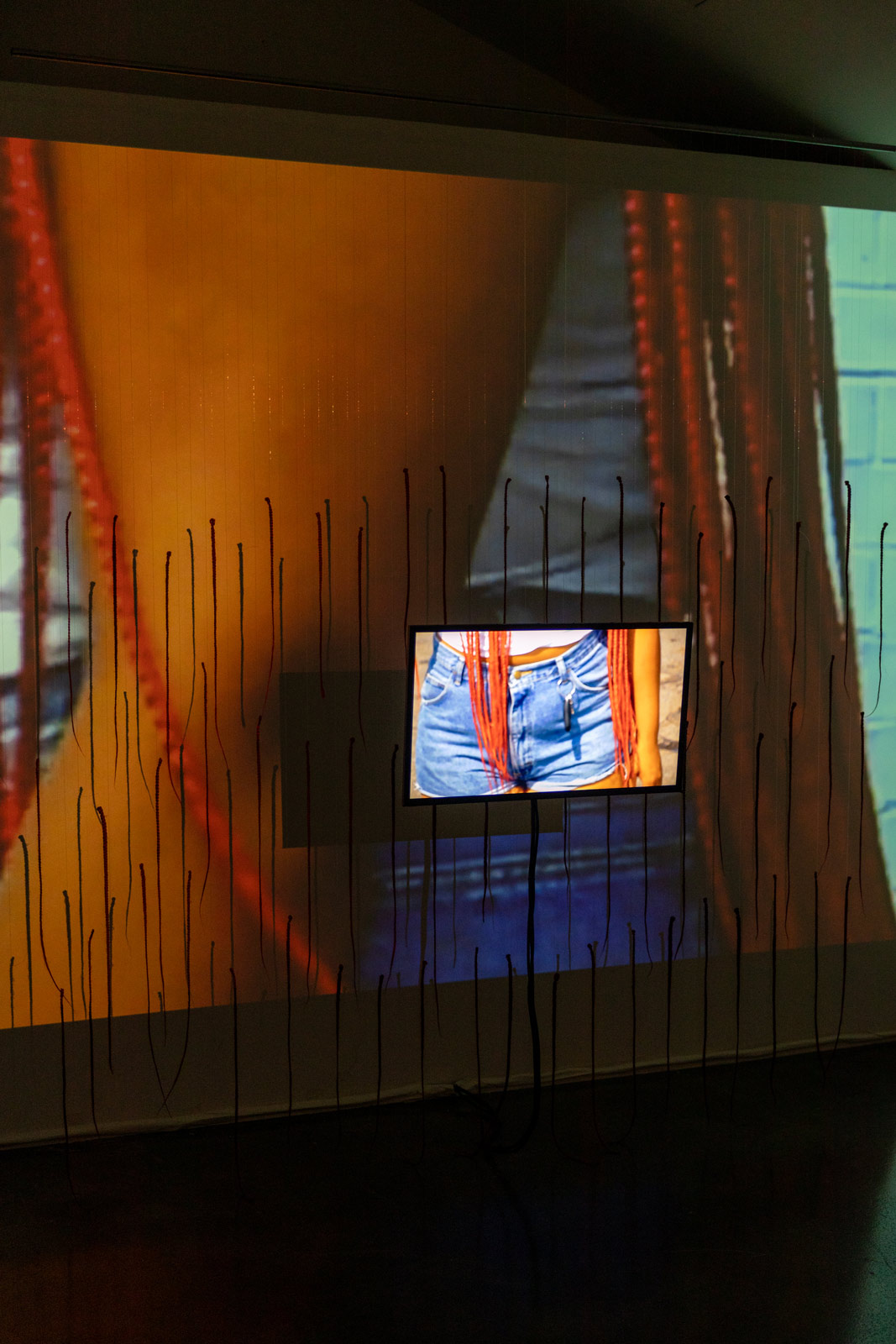

This weekend marked the opening of Downey’s first museum show: Orchid Blues, on view at MCA Santa Barbara through December 23. Meshing sculpture, film, photography, performance, and the written word, the artist mediates the “bounds of world-building and survival artistry,” zeroing in on the tradition of the blues, applying laser-focus to the mundane objects that populate Black life.

Downey’s work is “anti-disciplinary” à la David Hammons—ready-made sculptures that transform the quotidian, teasing out their value and what they hold within. Sometimes, the latter is undertaken quite literally, as with Lord Split Me Open, the titular piece for Downey’s last show at Hair + Nails. The four-part installation united a sawed-in-half leather couch, a glass side table, and a print of an old family photo, mounted on the gallery wall. “How do you tap into this very insecure network that’s making up a memory?” was the question at the exhibition’s center. “Sometimes, it’s just like the space between the steel frame, the space between the cushions, holding the residue of every time you sat on it or walked past it.”

Here, the pair of artists carry on a years-long dialogue—getting to the heart of Orchid Blues, the practice of junk-collecting, and what it means to make art on your own time.

Morgan Becker: Tell me about how you two met.

Cameron Downey: Caroline was one of my teachers at this nonprofit youth arts organization called Juxtaposition, located on the Northside of Minneapolis, which is where I grew up and still live now. She and her husband, Nate, were my first art teachers in some ways. They were really formative in my decision to pursue the arts, and also how to think about art in terms of what it means to have a concept, and stand beside it. And also, you know—what it means to be a Black person making work in a field that is obviously pretty Caucasian.

Caroline Kent: [Laughs] I mean, at Juxtaposition, I didn’t necessarily separate teaching young people from teaching college kids. The freedom we were allowed was pretty amazing. We [were able] to bring in real life and the neighborhood. Visiting artists would come into the Walker, and meet with the students. I mean, I remember Xaviera Simmons coming in, Jamal Cyrus, Theaster Gates. Cameron, I met you around the age of 14. We had an extraordinary group—Namir Fearce and Aislinn Mayfield and you. We didn’t cut corners on explaining anything, and all of you met that challenge.

Cameron: Almost everybody that was in that cohort are practicing artists to this day, which is really reflective of how [it shaped] each of our lives. I remember having hours-long discussions on why Beyoncé is blonde, and what that does for her as a pop icon.

Morgan: In a tangible sense, Cameron, what of that education shows up in your work today?

Cameron: I remember learning about artists like Mark Bradford—specifically this performance piece where he had on this Victorian-era dress [made] of a Lakers jersey, and he was playing basketball. That was really informative to how I think about video art. I learned about Rashid Johnson; there’s his phrase about, ‘a table being something to put something on.’ It got me down to the basics of, like, What are the objects that surround us? What’s their use, and why do they have those uses? I’m putting materials first—finding carpets or mattresses or pieces of leather, things that have all been touched. What does that material have to say? What I can add to that conversation is very much informed by that one line.

You and Nate used to make us go on walks around the Northside. It’s, like, the intersection of Broadway and Emerson, which otherwise would seem a little bit abysmal: It didn’t have much shade, and there was a tornado that went through it not too long before. There was a lot of stuff on the ground, and that was the focus. I think I carry it with me, as a practice. I love to just meander, and later found different words for it. The French call it the dérive, which is basically a purposefully pointless walk, as a means of political praxis. That particular term was connected to the Letterist International collective of artists in the ’50s who were heavily informed by Marxist and anarchist tenets. Like, what does it mean to stray from capital-T, capital-S The Spectacle and be okay with the minutiae of walking these blocks? A lot of my work today is still junk-collecting, and being informed by the shape of detritus.

Caroline: I remember passing storefronts that were vacant, and thinking about them as potential sites for something great to happen. This was definitely influenced by that visit from Theaster, early on. I was thinking about the stigma that the Northside held for outsiders, and the way that we would casually walk around—the impact it might have on young people to look for things inside their own city, because familiarity does sometimes change our relationship to things. Looking for something that could potentially become an art object is a way to re-see the environment. We’d laugh, because somebody brought back chicken bones. But that was a common sight! We brought them in and we thought about them. I was really impacted by that, as well, because I’m not certain that my own art education was that in touch with environment. It leads me to think of your studies of environmental science, and how that’s influenced your practice.

“I feel the blues were diaristic in a way—this ongoing journal on personhood and navigating the world. It’s the drawing-out of those small moments, from the deep recesses of one’s experience.”

Cameron: That was definitely informed by an intimate relationship with the parks and the lakes and the streets of this place—Minneapolis, the Northside specifically. My first mystical experiences with the land were in these swamps and marshes, really lush places. I think the relationship between a scientific practice and a conceptual or grounded art practice is rooted in making hypotheses about things. Like, Let me make guesses at it. Let me gather evidence about it. You’re making if-then statements always with art pieces, and trying to convince the viewer in the way that any successful research project does.

Also, whenever I’m trying to make [an abstract shape] with no purposeful form, it ends up kind of natural. My mattress piece [613 Fountain] felt like layers of stratified rock. Caroline, I see some geologic forms in your work. I know you’ve been focused on language through shapes.

Caroline: I was reading through Audre Lorde’s ‘Poetry Is Not a Luxury.’ I thought about what she was saying about the dark, the ancient, and the deep. The pulling-out from there. The one way I connect with that statement is that these forms that I’m inventing or recalling or misshaping come out of this blackness, which becomes a metaphorical site for some kind of unknown, something that’s always been there. As much as I think I’m trying to invent new forms to produce this language, I know they’re all based on things I’ve seen in this world.

I think that’s interesting to think about, too, with your practice. I thought of Robert Morris with your mattress piece. Your work draws the viewer close through the familiar, through something that resembles something else. But then you get closer and you encounter an object that actually has a very specific function in social history. Beyond that, maybe there’s a layer of personal reference, to the bed that connects to Black life. It could read as a kind of abstraction; I think of abstraction [as something] right beyond the familiar, right to where you might not have language for it. Then the other senses come in.

Cameron: I think you’re very right that there’s a synthesis that’s happening, that’s not always conscious or intentional. Like, I am taking in a thousand things. And I think any responsible artist is willing to say that nothing they’re doing is new.

We both read this essay called ‘The Timeless Blues’ [by George E. Lewis]. It talks about the genre, but also just [about the] blue sentiment—blues living as being naturally recursive and sort of circular and punctual. It’s, quote-unquote, ‘always already there.’ In a lot of ways, that’s positioned against theorists like Nietzsche, and Western concepts of time. It touches on the curse of Sisyphus, that to have to do something over and over again is hell. But with the blues, and in an African sense of time, the now is what matters. There’s always an immediateness; things don’t have to progress. And, in fact, maybe they don’t. And that’s okay.

Caroline: Enduring nature that doesn’t go forward.

I’d be curious to hear you talk a little bit about the history and the process behind [your couch piece], Lord Split Me Open.

Cameron: It is both short and long [laughs]. Because there was a couch that I had, and I was like, I really need to cut this in half. But also, I knew that I wanted to imbricate an image inside of it. A lot of the show is [about] the key role that accidents and serendipity play in memory. I thought of the [idea] that, each time a memory is tapped into, the less secure it becomes. I found all of these images that, for 10 years, I hadn’t had access to, and was thinking of ways to unearth what their feeling was. Like, how do you tap into this very insecure network that’s making up a memory? Sometimes, it’s just like the space between the steel frame, the space between the cushions, holding the residue of every time you sat on it or walked past it.

I’m interested in ready-made objects. That piece is a four-part installation that includes the table on the wall, the two halves of the couch, and this print in between them. The table is maybe my favorite aspect, because it incorporates this practice of finding things that I like, in junk stores or on the streets. I can throw it on the wall, and it is now the thing that I have said it is. That, for me, is a way of reclaiming my time. The ready-made is proof of that: At one time, it meant a different thing. You associate it with Duchamps and whatnot. But I also associate it with the kind of wit that David Hammons has. Like, You’ll take this, and it is what it is. This is what I have decided that it is. There’s power in that. And also, I don’t think that I should have to—amongst all the other things this life is forcing me to do to survive—spend thousands of hours on any one piece of art. I want my time back, and I want it manifold.

Caroline: We’ve talked about this. You made a statement that you believe there’s a moral position you take, with making work just for pleasure. I definitely think there’s a paradigm of living that says we constantly need to make, produce, continue on. Those paradigms are traps.

There’s even something biblical [about the couch piece]. I can’t help but think of layers of the earth. I remember [this verse], something about, If my people don’t praise me, the rocks will cry out. I always thought that imagery was so dramatic—these big rocks being split open, performing something in nature that we can’t quite understand. The living room becomes the landscape, becomes the crying-out, the breaking-forth. The familiar gets ruptured through memory. There’s this reorientation of home life as you grow older. I remember going back home [during college] and being like, Was my house always this small? The ceiling feels so low! I’d grown in my experiences; coming back, the perspective had shifted. And that’s what I encounter in your work. You seem very invested in objects that have been touched, lived on, worn down, stepped on. All these things, imbued with bodily experience and exchange.

“I want my time back, and I want it manifold.”

Cameron: I’m making another body of work for my show [Orchid Blues] in Santa Barbara. In a lot of ways, I’m taking that concept and really expanding it—that the use is the value in an object, the fact that it was turned over and over again. That it was loved. It feels very fulfilling to extend these objects that same tenderness, [carrying] on the legacy of an item.

I was talking to one of my friends and interlocutors, Namir, about what it means, as a Black person, to be collecting junk. And how that’s positioned against—for so long—not having anything. Like, I will cherish all of these small things, anything that I can find that’s beautiful. And not necessarily make it more so, but try to puzzle it out, tease it out, split it open. Going back to the title of that piece—the ask for that is really intimate. To ask that someone see everything inside you, or to acknowledge that someone knows everything about you. Anything you’ve done, wrong or right, everything that you want to hide—having it be parsed through is really idealist and romantic to me. It connects back to the blues in some ways, because all of these things are already known. They’re already there with you. The ask to be split open is at once magnificent, and also sort of redundant.

Caroline: I feel the blues were diaristic in a way—this ongoing journal on personhood and navigating the world. It’s the drawing-out of those small moments, from the deep recesses of one’s experience—and not only of theirs, but of generations before. There’s definitely a cord that goes all the way back. Maybe that’s your desire to make things in serial: What is it like to do something over and over and over? What happens in the transaction of a menial task? Turning on an iron—that smell, the handle, the board, the cheap aluminum squeak, the unsteadiness. All those things are embedded in our relationships to these objects, over the course of a lifetime.

Cameron: There’s this passage from In the Break by Fred Moten, [that argues] that Marx and Saussure were inadequate in reading what it means to be an object or commodity, referring to [Aunt Hester’s] scream that pierces both of those things, and lets us know that any definition we’ve had up to this point hasn’t quite captured the condition of Blackness.

Caroline: It goes to a shifting of the constitution of being. Lord Split Me Open gets at that source: What’s in there? Where’s it at?

Cameron: I don’t think I’ve quite found it, and I’m alright with that. So I’m gonna keep singing the blues.