Billy Bultheel joins Document after the production’s premiere at Berlin Atonal, expounding upon its influences, from church pews to Jean Genet

Billy Bultheel’s compositions have spanned the worlds of art, architecture, dance, and fashion—and now, he’s taking them all back. The composer and performance artist premiered The Thief’s Journal on September 15 at Berlin Atonal, the 10-day sound, art, and music festival located in Kreuzberg at Kraftwerk, a former East Berlin power station. “It’s a bit [like I’m] reclaiming the music I’ve been writing for other people,” Bultheel told Document following the performance. “[And showing] that there is a sort of a red line that goes through my work, even when [it’s undertaken] with other people.”

Bultheel’s collaborators include Anne Imhof—for whom he composed the soundtrack for Faust, which won Germany the Golden Lion at the 2017 Venice Biennale—artist Eliza Douglas, and more recently, artist James Richards. A series of performances, including Mt. Analogue, which was executed last April at Paris’s Bourse de Commerce, paved the way for The Thief’s Journal, developed with the curator Marie-Therese Bruglacher and later adopted into the Atonal program. The production is also part of an extended program called Cadences, a series of audio-guided runs developed for the Nike Run Club App, co-curated by Atonal and REIF.

Bultheel took the title The Thief’s Journal from Jean Genet’s 1949 novel of the same name. Part fiction, part autobiography, the book follows its protagonist’s adventures through Spain, Italy, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Nazi Germany, and Poland as an outsider and homosexual; he frequents bars and flophouses, has love affairs, and commits crimes. “It’s my journal, and I’m stealing my own works back,” said Bultheel, referencing what Genet’s work meant to him.

The massive 1960s brutalist structure that is Kraftwerk Berlin has a starring role in the production. “I’ve always been interested in the interplay between music and architecture,” said Bultheel. “This is something that—in the Renaissance, when a lot of churches were being built—was very actively being thought of: how music was going to be distributed throughout the space.”

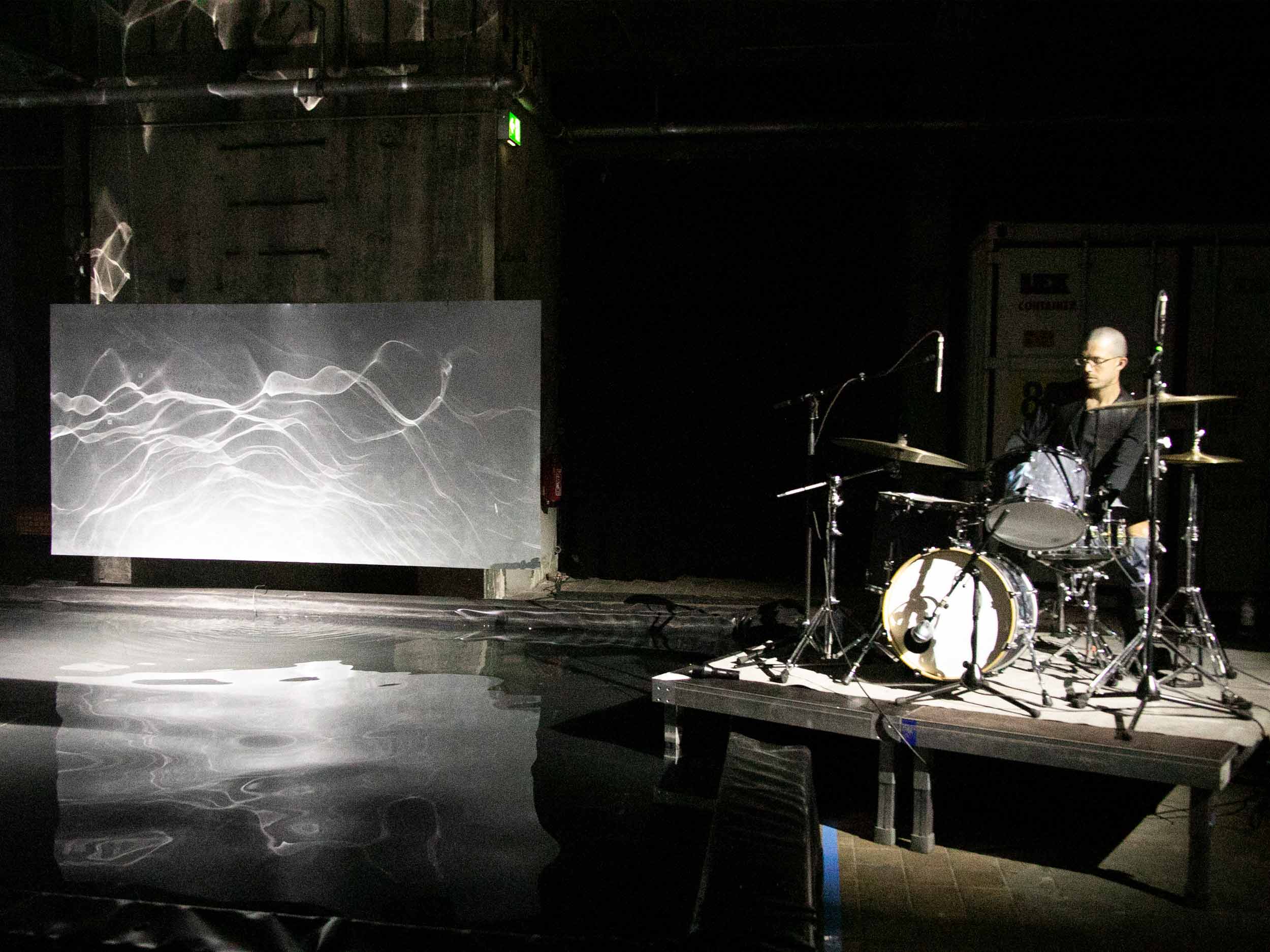

Last spring, Bultheel consulted with curator Marie-Therese Bruglacher and architect and scenographer Andrea Belosi to find the perfect space within the industrial concrete building. They selected an area on the second floor, using scaffolding to build a stage that viewers could look up to, constructing a shallow pool of water and two large metal plates that served as both a backdrop and percussion instruments. “The scenography is basically reminiscent of these Renaissance church structures,” explained Bultheel. “A lot of the towers represent balconies that choirs would sit on, for example, or a pulpit that you would find in churches. There’s a little bench, which is like a church bench. The plates almost become an altar.”

In designing the costumes, REIF founder Marcelo Alcaide asked himself one question: How can the visual complement the sonic aspect of a performance? He put together pieces by Tanya-Viviana Abelson, jewelry brand RÄTHEL & WOLF, and Nike. Alcaide mixed high and low culture using sportswear, rubber, latex, cut-out tops, and anoraks that could double as religious garments. “It’s a reflection of the sound, and how these garments can be a representation of a contemporary Baroque Renaissance,” said Alcaide.

Nine musicians performed the piece, including a euphoniumist, a saxhornist, tubists, flutists, drummers, and an opera singer. They immersed themselves with the audience as they walked to the stage, generating what Bultheel hoped was both intimacy and brutality. The sound came from all directions, providing a sensory experience. “I want to embed the audience within the landscape of the music itself,” said Bultheel, “so it’s not just a picture being looked at, but rather a picture that is being lifted through the audience, really placing them right in the middle of it.”