The Nashville-based band walks Document through their summer tour, untangling their intent in the process

I’m not entirely sure egg punk is real. The more time you spend with it, the more the whole thing kind of feels like a mass-produced prank by internet punks. I’m not alone in that sentiment, but ever since the nominal delineation of the subgenre, something has sort of derived from it: The bands that occupy the playlists and paragraphs-long YouTube comment explainers do conceivably fit within its convoluted definitions. But there’s nothing particularly unique to the shared traits of its bands that really departs from what punk is broadly supposed to be: weird, agitated, and—maybe most importantly—DIY in approach.

The accessibility of punk is what once made it kind of beautiful. Feeling over finesse. Even when the finesse is really fucking good. But as more and more bands claim the genre, the less cool it seems. A lot of self-proclaimed punk bands feel commercial, even when they lack the money or prestige that commerciality offers. And thus, its ill-explained branches propagate—subgenre as proof of real punk sentiment.

Nashville’s Snõõper is one of those bands, though not self-defined as such. They are frequently classified as egg punk, as they embody its mostly agreed-upon core qualities—weird and bouncy and off-center. But the band is largely (and intentionally) phlegmatic about such categorizations. Genre is hardly a concern. Music barely was. Snõõper emerged without any real intent of becoming a band at all. They didn’t imagine an album or a tour or an Anthony Fantano dissection of their record. The egg punk codification—however pretentious—is undoubtedly cool (especially where it’s not self-ascribed), but it’s also what scares them. Snõõper was made wholly from impulse, and any analyses might taint what’s to come next.

But we want to categorize it. We sort of need to. We’re always mentally playlisting, which isn’t a bad thing, per se. I like to categorize. I want to say that Snõõper is akin to Frank Sidebottom in tangibility of concept, and DEVO in ideological scale, and Bad Brains in speed, and Ween in comical dexterity, and Dave Grohl in social personability, and Death Grips in distaste for speaking between songs during sets. But the more you attribute, the less your attributions mean. I guess egg punk is the closest we’re going to get to something singular for Snõõper.

Following a tour that followed an album, the band unpacks their accidental origins and the making of their music.

Megan Hullander: How did your tour come together? Australia and the West Coast of the US feel a bit locationally random, though it sort of makes sense scene-wise.

Blair Tramel: Connor is a bartender, and when he gets off work he has to wind down. It’ll be 5 a.m., and I’m always like, ‘What are you doing up?’ And he’s talking to a bunch of Australians online. It was really just internet friends. And a lot of the bands that we’ve played with over there have played Goner Fest in Memphis. We housed them when they came through Nashville, so they returned the favor for us.

Megan: It’s funny, because the Pitchfork review of your album said something like, ‘You have to see egg punk live to get it.’ But I feel like the scene’s core is virtual, because it’s relatively small, and the bands are all over the place.

Connor Cummins: Some of that is because of COVID.

Blair: It’s people in the middle of nowhere in their mom’s basement. There were so many times I’d be stoked on an egg punk band, and I’d be like, ‘Come to Nashville, play a show.’ And they were like, ‘Well, we don’t have any members in the band.’ ‘Well, you’re my favorite band online right now.’ But they’d never played a show. So many of the people in the US within our genre—if we did see them live, and if they did have a band—did not sound the same at all.

Connor: I guess, even before COVID, there was the tape trading culture within it. That, Here’s a demo of this thing. I wrote two songs. They’re all a minute long. It’s definitely a community.

Blair: I think, in Australia, the egg punk bands do it different. That’s why we wanted to go, because they are playing live. I don’t know… The freaks there are not freaks in the same way as they are here.

Connor: The Australian’s have their own sound—a lot of the early American egg punk bands didn’t really have synthesizers. There was a weird period where people were calling our band synth punk, and we’d never had a synth on our stuff.

Megan: I always wonder if there’s truth to the really detailed analyses of music, or if it is more incidental like that. Like, the review that Anthony Fantano did of your album was like, ‘Their songs are so short because they hate the idea of repeating an idea.’ But I’d think that sorting the length of a song is just more instinctual.

Connor: Honestly, the truth about the shortness of the songs is that I can’t play drums that fast for that long.

Blair: [The speed] matches the way that my brain works. I love to do a quick song and then move on to the next one. When we first started playing live, I did not understand that they had to stop and tune their guitars. We played and I was like, ‘What the hell was that? Why did you stop?’ I do not do banter. [I use] samples now so we can all take a drink of water or tune, but it doesn’t feel like I have to say anything or like there’s an awkward pause. It’s a nonstop wall of sound.

Megan: Was it tough, translating the recorded version to the live show?

Connor: When we were [writing], a lot of the songs were brought together really quickly. I’d be like, This guitar track is a little sloppy, and I could probably redo it, but we were just so stoked that we rushed everything. When we booked our first show, we were like, Alright, we just have to strap down. We practiced every single day, and now it feels super tight.

Blair: The thing about Snõõper is that nothing was planned at all. We never even really intended to start a band. We did it without even being aware of it. I would do a visual element to go along with [music that Connor made]. I was like, I guess I’ll sing if I can do the video. I never wanted to play a live show. It was that egg punk ethos: We could be anything we wanted to be aesthetically, and we got to really curate our own image. I think we fall so much outside of the egg punk genre, really.

“The thing about Snõõper is that nothing was planned at all. We never even really intended to start a band.”

Megan: I mean, I think it’s easy to categorize you guys as egg punk because the synthesis of debates about what it actually means sort of boils down to the tongue-in-cheek attitude and DIY sensibilities. But I feel like that is just a part of punk more broadly: The I don’t technically know how to do this but I am going to just do it because I feel it ethos.

Blair: It’s just another way for punks to be like, You’re not included in this. The egg punk thing is funny, because we definitely fall into it. But we’ll put out a new track and, inevitably, someone’s like, Sounds like The Coneheads. Well, it sounds like you don’t really listen to much music.

There’s some of that [attitude] in all punk. I’ve been going to punk shows forever, and there’s this feeling, like, You’re not punk enough to be here. Now we’re in this fun era of punk and it’s like, You’re not weird enough to be here.

Connor: I would also say that the difference is that mostly all the egg punk bands have an eight-track. There are bands that I would consider garage rock, but they’re called egg punk because it’s [recorded] on lo-fi tape. The difference between hardcore is just what Blair was saying: the aggression. I think egg punk fans just want to have fun. But it also all came from a meme that was made a couple of years ago: chain punk versus egg punk. You’re either a hardcore dude or you’re a weirdo. I think both sides hate the terms, but it is what it is. That’s just what people are gonna call it.

Megan: Well, I think all it takes to be chain punk is taking yourself really seriously.

Connor: Like, incredibly seriously.

Megan: Whereas I feel like your stuff is rooted in the opposite of that, where the craftiness is more silly. Do you guys have concepts for what you want songs to be, and you piece the idea together from there, or is it more you have a mass of material you want to include and then you find a concept across them?

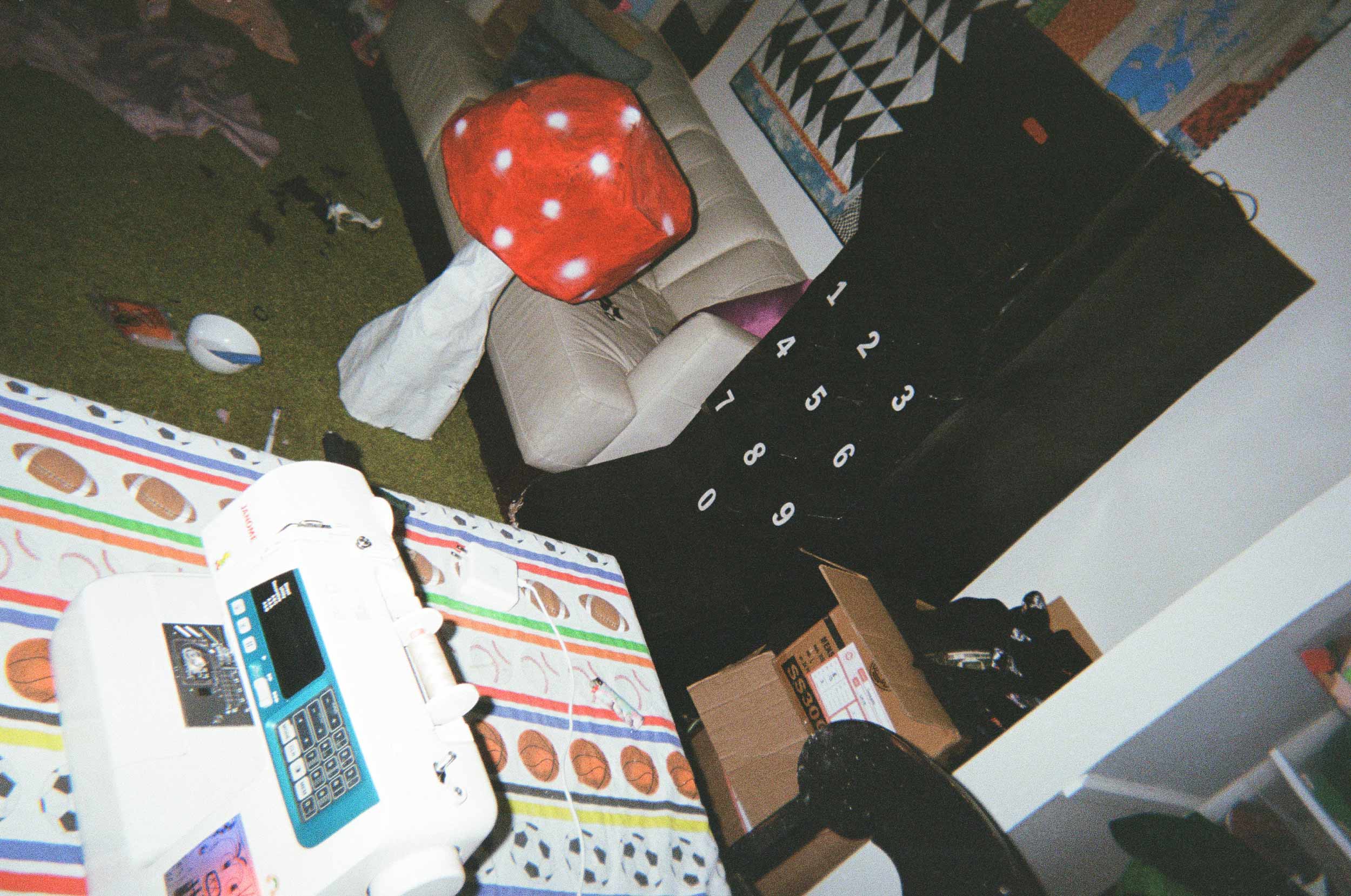

Blair: I originally wanted to record the songs around an idea for a music video. Like [for] the song ‘Fitness,’ I had made this weight, and I wanted to make a video around that. So Connor made music. And then when we started playing live, I was like, Oh, no, I can’t sing at all. But if we have all these props, maybe they’ll be so amazed that I made these and they won’t pay attention to the mess of my vocals. But every day [on tour], the bug puppet was breaking, and I’d have to replaster the eye, and it just ended up looking more and more bootleg.

Megan: I’d think the sweat of one show alone would be enough to erode it.

Blair: Oh, yeah, the sweat is really real. Those pictures [we took on tour] should come with a scratch and sniff. On the West Coast, it was obviously summer and so hot and the tracksuits would get so wet. But you find something that works for you—like an outfit or whatever—and you want to stick to it.

Connor: Well, you suggested the tracksuits.

Blair: I love the tracksuits. I just want everyone to have a backup because they smell.

Connor: Blair bought my first tracksuit just for fun, and then we played a show in November and it made sense to wear it because it was cold and it just looked cool. And then everyone else in the band decided to get tracksuits. And then one of us started doing a kick during the beginning of ‘Fitness,’ and then we all started doing a kick. Then, eventually, we wrote choreography for the whole thing, but it all just kind of happened by accident. Nothing is planned in advance.

Blair: That’s the thing—it’s been really exciting that things have been going well. But we went from not ever thinking we were gonna play live to then playing the Roxy, and having all this amazing stuff happen. I personally try not to read anything about the band; I just want to keep it fun all the time. I think we all feel this pressure, because people are watching us now. But I think you can tell when a band is cool at first and really genuine, and then they just stick to that formula.

Connor: We don’t want to write the same song again, but we don’t also want to write something that sounds like a brand new band that alienates our existing audience. We’re trying not to think about it too much.

When we finished the record and made sure all the parts were correct, we didn’t listen to it for, like, five months.

“We don’t want to write the same song again, but we don’t also want to write something that sounds like a brand new band that alienates our existing audience.”

Blair: I think, with the new record, we thought that people might think that, in a way, we were selling out. Because it was like we went from home recordings to these hi-fi recordings—we like to think of them as club remixes.

We’ve gotten a lot of support from different people. But in my world, I’ll show people, and they’ll be like, ‘So, who’s in the band?’ And I’m like, Me! And they’re like, ‘You’re making the props?’ And I’m like, I’m in the band! ‘You’re doing the shirts?’ I’m in the band! Even my parents still cannot figure out what’s going on. They’re supportive, they just don’t get it.

Megan: It’s funny how the nobody gets me stuff follows you into adulthood, because it feels like such a teen thing. But even when you become a ‘real’ adult, it doesn’t stop.

Blair: Oh, it doesn’t. It’s never-ending.

Connor: Even music people, though. I feel like every time we get a review, there’s some connection to egg punk. But then people who don’t know about egg punk say it’s like Jay Reatard, or it’s like DEVO. It’s all over the place all the time, which I guess is a good thing. If everyone thought we sounded like one band all the time, it would be boring.