Working across mediums, the author of ‘Working Girl’ grapples with the contradictions of life under capitalism—complicating notions of consent in a totalizing system

Art and sex shouldn’t be commodified—or so we’re told. They’re “seemingly sacred forms of human expression,” Sophia Giovannitti writes, describing how, despite this, the industries attached to them have come to serve as stress points—saturated with hyper-capitalist relations, and operating on the fringes of the formal economy. Both are filled with “wildly stratified price points, scams, blurred legal lines, exploitation”; both “traffic in the ability to produce a feeling in another person.” This is the subject of her book Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex.

When Giovannitti first started working as an escort, she found that fucking for money did not have an impact on what sex meant to her in her personal life. Rather, the high hourly rates and flexible schedule allowed room for other aims: making art, learning, becoming herself. This is one of the industry’s best-kept secrets: By making pleasure one’s work, it becomes possible to work less. Plus, she says, “I don’t actually think it’s possible to take sex out of the workplace. The dynamics of exploitation in waged work under capitalism are inextricably linked.”

I’m not a sex worker, but I can attest to her argument. My work—the creative labor of writing—enters the bedroom all the time. It takes the form of conversations with my partner; late nights hunched over my laptop working on last-minute freelance assignments; anxiety about money; the precarity of the magazine industry, and therefore, my job; the sex I’m not having, because I’m exhausted or stressed or both. This is what Giovannitti is getting at: There’s a pervasive idea that by selling sex, you’re giving something up, polluting something pure that would remain otherwise untouched by capital. The reality is, of course, that something has already been corrupted. “These are the foundational coercive structures that we’re all living and working under,” Giovannitti says. “I don’t think anyone should have to trade sex to pay rent, but I also don’t think anyone should have to trade labor of any kind to do that. I find inspiration in the workers and thinkers on the margins who lean into the criminality of sex work—operating with a desire to subvert dominant systems as opposed to being assimilated into them.”

This, Giovannitti says, is what drove her first to sex work, and later, to writing about it. Her art, too, addresses this topic: In her 2022 performance piece Contract, she spent the duration of the show inhabiting a bed in the center of a white cube gallery space, only accessible to those who paid a thousand dollars for entry—granting access to the art and, by extension, the artist herself. It was an open invitation: In exchange for money, Giovannitti asked her visitors, What do you want in return? Then, she began negotiations.

“A fantasy persists that capitalism is not a totalizing mode of domination… that preserving these sacred, emotional, creative, and interpersonal spaces apart is, in fact, desirable, and possibly even transgressive. This is untrue.”

Sex work is not the sole subject of Giovannitti’s art—rather, she’s interested in the way the two overlap. Often, she finds herself moving as a double agent between two cultural spheres: She is at Art Basel, mingling with her collectors; she is in a hotel suite, fulfilling the desires of her client. Giovannitti writes of these twin identities in Working Girl, describing how, by compartmentalizing her own explicit commodification via sex work, she is able to minimize her acquiescence to the demands of capitalism in everyday life.

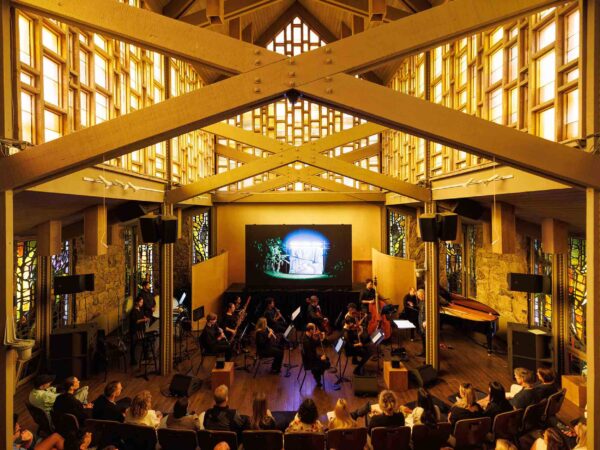

There are also multiple Sophias in her performance lecture, Scorpion, Frog, which I attended in Chinatown on a sweltering summer day. The first thing I noticed was the sculpture in the center of the room: Sophia Zero, a 3D-printed rendering of her body on all fours that she later broke in two as part of the performance. Then, there was the childhood photo of Sophia, pinned to the wall behind the real one, who stands at a podium wearing a black, bondage-inspired top. From where I was sitting on the floor, I could see she was barefoot, with vaguely iridescent polish on her toes. The room was crowded, though the audience was capped at a dozen people per night—all of whom were now cramming themselves into nooks and crannies, waiting with bated breath for the show to begin.

In the first minute or two of the performance, Giovannitti explained how she began seeing a client with a friend of hers: the CEO of the company the pair then worked for, who later became her collector. They had advertised their services together, she said, implicitly offering a twin fantasy: two brunette artists of the same age, superficially similar in appearance and affect. Over the course of the 90-minute performance, she interrogated the imbalances of wealth and power that characterized their dynamic, excavating her own vulnerabilities and connecting these experiences to those of sex workers more broadly: weaving in stories of a police sting targeting a happy-ending massage parlor, and an investigation of child porn and sex trafficking. The personal is, in her work, inevitably political: “I’m fascinated with sex, gender, power dynamics, consent, and I’m fascinated by my own experiences.”

Giovannitti may have come up in a capitalist world, but she was also raised by activist parents—and her family tree is studded with other such figures. “My great-grandfather was an anarcho-syndicalist labor leader in the Northeast US in the early-1900s,” she explains during Scorpion, Frog. “He wrote the introduction to the English translation of Émile Pouget’s book Sabotage. He said that the first form of sabotage consists purely and simply in ‘going slow’ and ‘taking it easy’ when the bosses do the same in regard to wages. The second form consists of confronting a real and deliberate trespassing into the bourgeois sanctum—a direct interference with the boss’s own property. It is only under this latter form that sabotage becomes essentially revolutionary.”

One can see the reflection of this thinking in Giovannitti’s own practice. She is attracted to scams and subversion; the art world and sex industries are both fertile breeding grounds. Yet her willingness to appropriate the tools of capitalism to subvert the status quo contrasts the approach of her family, who she describes as “artists who refused to commodify their art.” Giovannitti’s father turned instead to the “honest work” of home construction, believing that this would support a boundary between art and labor. Yet his practice remained “touched by capital in every way”: his art-making flattened into what little time he could find on the fringes of his 60 and 70 hour work weeks; limited to low-cost materials; abandoned in the midst of busy spells at work—much like our hobbies, our passions, our leisure time, and often, our sex lives. “A fantasy persists that capitalism is not a totalizing mode of domination… that preserving these sacred, emotional, creative, and interpersonal spaces apart is, in fact, desirable, and possibly even transgressive,” Giovannitti writes in Working Girl. “This is untrue.”

“In sex work, the concept of consent often falls short. There’s this quote by Heather Berg: ‘How should we talk about consent when there’s rent to pay?’”

Effectively, these incomplete gestures toward progressive thinking only propagate the system further up, Giovannitti believes. This is because the refusal to commodify art and sex implies that there is another path, one where the impact of capitalism can be evaded without overthrowing the system entirely. It is this refusal to acknowledge the system’s totalizing influence that allows us to justify existing within it, turning our gaze away from the fact that—even in our leisure time—our lives are structured around work. Giovannitti references Foucault’s assertion that power is not exercised over us, so much as it is produced and reproduced in relation: both by our participation in normative institutions, and our resistance against them.

The notion of consent in sex work is another subject Giovannitti wants to complicate. “I’m interested in moving beyond consent as a framework, period,” she says. “There are these intense gray areas that every single person in the world inhabits, including at work—and in sex work, the concept of consent often falls short. There’s this quote by Heather Berg: ‘How should we talk about consent when there’s rent to pay?’”

No means no; sex work is work. “These phrases are an oversimplification,” Giovannitti says, noting that they’re intended to push back on very basic misunderstandings of gender and power dynamics. “Both serve a purpose, but they also erase complexity in a way that’s become harder to talk about. I just can’t believe consent has become the dominant way that we talk about sex—because I and so many people I know have had horrible, exploitative sexual experiences that we have said yes to. When it comes to talking about consent in sex work, a lot of people are afraid that whatever they say will be twisted and used by the anti-sex work camp to justify this idea that all sex work is implicitly rape,” she says, noting that this is harmful both to the movement and to individual sex workers—because if your work is considered a violation of consent by default, how do you talk about an experience with a client where you were raped? “People have complicated experiences in their lives, and under these conditions of capitalism, no one is making decisions that are purely great, or purely exploitative,” she says. “‘Sex work is work’ is important, but it has also been co-opted, with people saying there should be workers’ rights, but also regulation and taxes. That’s not what I think. I don’t want to make it out to be a job like any other, because it’s not.”

Even as she turns her keen analytic gaze on the forces that structure modern life, Giovannitti is equally willing to interrogate the flaws in her own thinking: “In the book, I talk about a period of my life when I worked so much, and I felt exhausted and dissociated. I started to realize that I was subconsciously creating situations where I was mistreated, in order to give myself an excuse to do whatever I wanted—to act vengeful and cruel to those who owed me this unpayable debt,” she explains. “That experience led to the genesis of Scorpion, Frog.”

At times, Giovannitti’s practice—that of delving into enemy territory, of assuming the subordinate position with intent to flip that dynamic on its head—leads to a collapse of boundaries between her artistic persona, and the one she assumes as a sex worker. “Over the years, I’ve had plenty of straightforward experiences where the exchange is clear: someone wants something really specific from you, and it has nothing to do with love,” she says. Her relationship with the CEO and the other sex worker was different: There were real feelings between the three, underpinning the transactional dynamic of workers-for-hire. The two women fucked each other when the CEO wasn’t around; the CEO pitted them against each other, breeding feelings of inadequacy in his presence—twin tingles of competition and desire. “These are pretty standard workplace tactics: So many are predicated on these cycles of expectation and exploitation, and people are destroyed by toxic workplaces that have nothing to do with sex,” she notes. In the end, the CEO screwed over a different friend of hers after assuring Giovannitti that he would treat their partnership fairly if she introduced them. That, she thought, is a debt that can’t be repaid.

In Scorpion, Frog, Giovannitti connects this idea to an ongoing project, Debt study, in which she interrogates “entrapment, vengeance, desperation, entitlement, entrenched structural power dynamics, and interpersonal cruelty”—in short, the issues that arise around people and money. These works include an audio recording of an interaction with a curator who failed to deliver on his side of what she calls a “doomed transactional affair,” effectively reneging on the conditions that structured their fucking. In the recording, it sounds like the pair are having sex, and that Giovannitti is saying no. “Other relationships, recordings, digital and paper trails, and failed owings have come under the umbrella of this study since, and my relationship with the CEO would come to form its apex,” Giovannitti states in Scorpion, Frog—elaborating, during our interview, about the intent behind documenting these experiences: “I can easily make myself sound like a victim, and there are times I have been—but I very much wield that power, too, and a part of this project was about me coming to terms with my desire for more of it. In the lecture, there’s a line where I’m like, I want to be in the all-powerful, unmerciful position—I want to be the CEO. I don’t just want to destroy the company and distribute its profits. There’s a part of me that does; I am anti-capitalist. But I have also come up in this brutal, unequal, misogynistic world. A lot of the desires that have been instilled in me are ugly.”

Her proposal is a radical one: Look honestly at the ways in which you are bound, so that you can one day be free. Giovannitti’s art practice, too, is defined by the frank honesty with which she analyzes her own unsavory attributes—informed, perhaps, by her ardent belief that those traits are a reflection of the sick society she was raised in, and that they must therefore be excavated. The fault is not our own, she seems to say; look deeper.

Giovannitti speaks freely of her privilege—both in Working Girl, and during our conversation. “It is because of my race and class position, my education, being a cis, straight-presenting woman, that I am accepted and subsumed into these intellectualized, monied worlds,” she says, describing how—rather than being further marginalized, as is the case for many sex workers already on society’s fringes—selling sex has provided her with new forms of personal freedom, as an artist, thinker, and maker. She is a fugitive, or maybe, a spy—using her access to these worlds to gather information, and hopefully, one day, deconstruct them from the inside. As a sex worker, she has rent to pay. And as an artist, she is playing the object, and becoming the subject.