Toronto photographer William Ukoh’s first solo show, ‘JANGILOVA,’ is a quest for unfettered independence

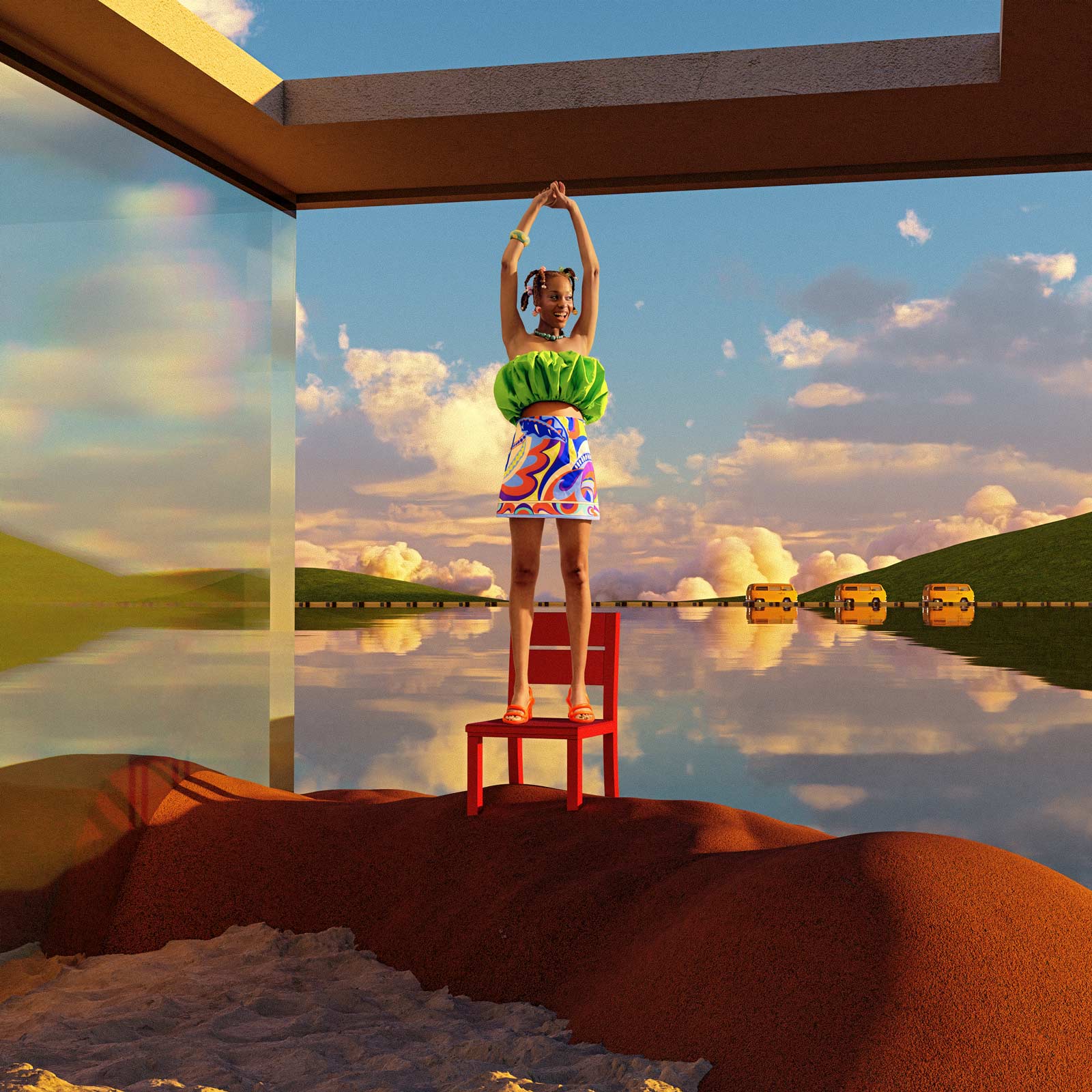

William Ukoh is fixated on freedom. Within the first 15 minutes of our conversation, the Nigerian photographer—now based in Toronto—employs the word 10 times. He means freedom in all forms: artistic, personal, financial. It’s a recurrent theme across his work— the Willyverse, as he calls it. From beauty editorials and celebrity portraits in GQ and Vogue Portugal to campaigns for Canada Goose and Holt Renfrew, Ukoh’s images are sensuous and surreal, layered with an Afrofuturist aesthetic where “leisure appears to supplant the abject,” as Connor Garel wrote in a 2020 profile of the artist. The artist’s most potent images feature larger-than-life subjects that seem to levitate—literally and figuratively—with an irrepressible exuberance in some vibrant paradise.

At Toronto’s Five Brock, Ukoh builds out his whimsical world with JANGILOVA. His first solo show takes its name from a Nigerian-English word used to describe an object with an oscillatory motion—like a swing or seesaw on a playground. Through film, photography, and installation, he uses the context of balance, creativity, and play to probe more deeply at his own conceptions of what defines freedom.

Here, Ukoh tells Document about his serendipitous career, his quest for unfettered independence, and the push-pull between making money and making art.

Josh Greenblatt: Tell me about the exhibition. How did it come to be?

William Ukoh: I did an installation in the summer of 2021 on self-care, and I think that experience opened my mind to the possibilities of doing installations, of doing something big. I’ve been doing [photography] professionally since 2019, but I’ve been shooting since 2012.

Josh: What was your gateway into photography and art?

William: I was surrounded by it my whole life. My mom was into art, I went to some arts camps when I was younger. It wasn’t until 2012 [that] I got reintroduced to photography through my oldest sister, and that was my first time [working with] a DSLR camera. I suddenly had this urge to tell stories. To finally have this tool that allowed me to express all the thoughts in my head was very liberating.

Josh: What were some of those thoughts that you wanted to express?

William: I was very interested in music videos. I like the format; I like how people told stories with music videos. Obviously, growing up, I watched a lot of Michael Jackson music videos, and I love how dramatic those were, just very expressive. At the time, there were lots of Kanye West music videos that I was very interested in as well. When I finally got this camera, I made a slow-motion film to ‘Say You Will’ by Kanye. And then outside of that, I did some stories where I had a lot of car [models], and made them characters. [I] did stop motion with candy—I was just doing a lot of things, nothing was really connected. But it was [exciting] to just experiment with this medium and to see where that took me.

Josh: And where did it take you?

William: In that first one, I think the general theme was around freedom. But the second time, I was revisiting freedom again and seeing if it still had the same meaning [to me]. And as I meditated on this exhibition, there seemed to be an [underlying] theme of freedom there as well—just in the way the characters [sat] in rooms, almost like they’re looking [at] this colorful, whimsical world outside.

“We’re exposed to so much that it’s always going to trigger something. But actually figuring out what you want to say is a whole different thing.”

Josh: Do you find freedom in structure or prefer no limits or boundaries?

William: I definitely find that structure helps me. I’ve always said that coming up with ideas is never a problem for me, because we’re consuming so much information all the time; we’re exposed to so much that it’s always going to trigger something. But actually figuring out what you want to say is a whole different thing, and I think the structure always comes for me when I figure out what it is [that] I want to say.

Josh: What does that structure look like?

William: It’s usually based on personal experience. Every year, I find that there are lots of conversations that point me toward a certain topic or thought or line of thinking—that’ll be the foundation. And then, in that thought process, I speak to more people, I meditate on the thoughts, see how [they’re] applied to my life, if I can draw on personal experiences. That builds a box that I [can] live in, and see how I can tell the story within these ideas.

Josh: Does your message or what you want to say change over time?

William: Yeah, I think that probably changes. I would like to revisit that first profile [of me by Connor Garel in The Walrus] to see what I said about freedom then. I probably said something along the lines of, ‘No fear,’ and I think that’s still true. But if I were to define what freedom means for me right now, I would say it’s just having quality choices, quality options. But then there’s still an element of not letting fear dictate the choice that you end up making.

Josh: How do you define freedom?

William: For the film in the exhibition, it’s pretty much just two people jumping on a couch. I can attach freedom to the general feeling that you get when you’re jumping on the couch, or you go frolicking in a vast landscape. There’s that general feeling of freedom that isn’t necessarily tied to tangible things, but then there’s also freedom [on the] Sundays that I’m like, I can’t believe this is my life, that I don’t have a nine-to-five to wake up to the next day. I can define what my day is going to look like. I’m happy in that way of life, and so that feels freeing. But it could also manifest in the work as well in what your process is, and how true you can stay to that process.

“If I were to define what freedom means for me right now, I would say it’s just having quality choices, quality options. But then there’s still an element of not letting fear dictate the choice that you end up making.”

Josh: What artists or movements, contemporary or historical, influence your work?

William: Historically, definitely [work from the] Renaissance. Just as far as lighting and composition, I don’t think you can get any better than that period. More recently, for this show, I noticed that I started aligning with some of the design aesthetics and color palettes of the Bauhaus movement.

In the Black space of photography, specifically, I think a more journalistic approach is being championed right now in the art scene. So it’s usually portraits, or lifestyle in a very specific sense. If you’re from a neighborhood that has ‘character,’—you could be in America, it could be in Nigeria, or Ghana, or wherever—capturing that lifestyle is what’s being pushed in the art space right now.

If you feel like you have to create in this way to get that attention and recognition, then chances are, you’re going to do that whether or not you really connect with that style of photography. But if we’re in a situation where a diverse landscape of photography styles is being pushed, I’m curious to know how that would influence the work that we’re seeing.

Josh: And it’s hard to know who’s influencing what, like the chicken or the egg.

William: I suppose there’s always that inflection point, and then things just start feeding [each other]. I wonder if, in 2020, that inflection point for Black arts was the Black Lives Matter movement. We’re not [that] far removed from that, so it makes sense. I wonder if there’ll be another cycle of an expanded type of art.

Josh: Do you find that your exhibition is lending new or greater context to your work?

William: I hope so. It feels like a culmination of something that I [didn’t] even know that I started in 2020. In that sense, if anybody that has been following my work attends the exhibition, it will feel different, but it will feel familiar. And for somebody that hasn’t seen my work, I guess they’ll be introduced to a certain chapter in my life, just in the colors that I use, the way the images have been presented—visually and sonically.

“As a child, you’re very free. I mean, subconsciously, you’re being shoved into a box with the systems and routines that you end up forming.”

Josh: The show is loosely divided into four themes: balance, creativity, competition, and money.

William: Balance was the first theme. The name of the exhibition is JANGILOVA—what we used to call, in Nigeria as a kid, anything that had that oscillating motion, so that could be a swing, that could be a seesaw. [From] 2021 into 2022, I felt very off-balance physically, I was having a lot of dizzy spells. Ultimately, it was really just burnout. I was experiencing that and I felt very off-balance in my life in general.

And so, when I created the images, that was now a combination of balance and the other thing, which is creativity and play. One day, I was on my way to the studio and I drove past the playground. [The kids] were on recess or something, and you could just hear them playing around; it felt very youthful, hopeful, very inspiring. But also, knowing the politics of the playground was also interesting to me. I had a very traumatic experience where I got pushed from monkey bars and banged my head. It was terrible. [I’m] thinking about all of these things and how to combine that with the idea of balance.

As a child, you’re very free. I mean, subconsciously, you’re being shoved into a box with the systems and routines that you end up forming. But there’s a freeness and a naivete that you approach life with that exposes you to danger but also exposes you to different modes of expression. As an adult, you end up building a box for yourself.

And then, money is money. You can talk about balance and creativity and all of these things but, at the end of the day, there’s that subtext of money that runs through our lives. As a kid, you don’t know it’s there. As an adult, it’s all that you can think about, because you have to live. And that also influences how you live as an older person as well. It’s unfortunate, but it’s a thing.

Josh: What’s your relationship to money as it pertains to your work?

William: I definitely try not to let money dictate how I approach my work, the types of jobs I take—but sometimes you have to be realistic. Sometimes the pay is good, and you do the thing. I think the more I’ve done it, the more selective I’ve become [with] the jobs I take. The money’s good, [but] the mental stress that you go through to just get basic things done becomes so weighted that it doesn’t even feel worth it.

Josh: So that’s another thing that structures both your work and your freedom.

William: Very true. One of the ways I’ve defined it is working less, and to work less I need more money. So yeah, here we are. Doing the thing.

JANGILOVA is on view at Five Brock in Toronto from August 17 through 22.