The crypto collective’s festival for the new internet scene ventures to transcend today’s technological hellscape, bringing forums (and paywalls) to IRL spaces

Idyllwild is a small hippie town on the edge of the Sonoran Desert, accessible only by winding mountain roads. The two-hour drive from Los Angeles gives a sense of retreat, as if the rocks that crumble off steep cliffs like giant white chocolate chips are bulwarks from harsher realities. This sense of isolation is perhaps why, in the ’60s, Timothy Leary and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love moved to this area to create a commune, living on a ranch where they manufactured lots of LSD. (It also seems fitting that the ranch is now owned by YouTuber Logan Paul.) Idyllwild’s hippie history offers visitors the sensation of partaking in a counterculture—a comforting feeling, even if it turns out to be a myth.

This August, I joined hundreds of hopeful futurists in the forests of Idyllwild for FEST—a three-day festival focused on forging a brighter era for internet culture. A precious optimism permeated the 700-person gathering, which was organized by the clout-heavy crypto collective Friends With Benefits. Offering more than just the typical debaucherous weekend of music and drugs, the festival was based on a tantalizing premise: bringing together “𝓪𝓵𝓵 𝓸𝓯 𝓽𝓱𝓮 𝓼𝓺𝓾𝓪𝓭𝓼 of the new internet” for an IRL meet-up, where perhaps—in between all the languorous lounging and passed joints—we might be able to figure out the best way to terraform out of today’s technological hellscape.

As a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), Friends With Benefits is a collective whose members are required to purchase a unique crypto token to make payments and cast votes on the group’s actions. The organization was founded in 2020 by Trevor McFedries, a digital entrepreneur perhaps best known as the inventor of online influencer Lil Miquela. Friends With Benefits successfully recruited members by marketing itself as a space for creative professionals in the art and music scenes, rather than Silicon Valley tech-bros; instead of hustle culture, it claims its values lay in “community” and “collaboration.”

Perhaps the most seductive draw of Friends With Benefits was its offer of reprieve from the “visual dogshit” aesthetic of an increasingly corny culture forming around crypto in the earlier 2020s. The positioning worked: By 2022, its numbers ballooned to 6,000 people, with celebrity members like Flying Lotus, James Blake, and Azealia Banks prompting the New York Times to describe it as “a V.I.P. lounge for crypto’s creative class.” The vibe at the inaugural FEST in 2022 was sumptuous techno-decadence: Tickets, which had to be bought on the blockchain, cost .5 ETH (about $927 at the time), and came with open bar access and unlimited gourmet food. Friends who attended that year raved about eating free steak dinners while attending lectures centered on web3’s potential to save the creative economy—including, as one homie put it, “Nadya from Pussy Riot talking about how crypto could save Ukraine.”

When the market crashed, so did dreams of a more prosperous future; Friends With Benefits savvily pivoted away from too much talk of a crypto-fueled revolution. This year, the festival opened its gates to a wider breadth of attendees by swapping entry via crypto token for a $400 ticket in boring old fiat currency. It also booked buzzy musical acts like hyperpop gods AG Cook and Charli XCX, Bowie-esque rockstar Yves Tumor, and indie princess Caroline Polachek to round out each evening—while the daytime programming included galaxy brain lectures from the likes of social media savant Taylor Lorenz, internet subculture researcher Joshua Citerella, and New York’s favorite downtown flaneur Dean Kissick.

“The festival was based on a tantalizing premise: bringing together “𝓪𝓵𝓵 𝓸𝓯 𝓽𝓱𝓮 𝓼𝓺𝓾𝓪𝓭𝓼 of the new internet” for an IRL meet-up, where perhaps—in between all the languorous lounging and passed joints—we might be able to figure out the best way to terraform out of today’s technological hellscape.”

As a lowly Substack serf, I obviously couldn’t afford the $400 ticket, but managed to score a free pass through festival sponsor New Brew, a drink containing kratom and kava—plants known for inducing mild euphoria. It turned out that the bar carried many trendy sober-curious beverages, including a Friends With Benefits-branded yerba mate containing adaptogenic mushrooms that they called “Metaverse.” This de-emphasis on alcohol contributed to a wholesome atmosphere that pervaded the festival. One afternoon, I zoned out in a meditative sound bath, before moseying over to a picnic table for a pop-up tea ceremony where attendees sipped pu-erh while trading tips on cannabis fermentation. My friends ran off to a creek for a quick swim, while I drifted over to a zine-making workshop hosted by Metalabel in a room where paper, scissors, and magazine cutouts piled on tables, with not a single screen in sight.

In fact, for a festival targeted toward the Extremely Online, the event felt remarkably offline. “TOUCH GRASS,” commanded scattered signs sticking out of the soil, referring to a popular meme amongst the chronically online, and I spotted many attendees unfurling their computer bodies on the ground, eyes closed while tapping their toes furiously to the music. Unlike many other festivals I’ve been to, the vibe at FEST was almost anti-hedonic, given that the music was mandated to end at midnight due to a local noise ordinance. (“Friends With Benefits?!” a friend overheard a local man grumbling at the local donut shop. “Is that a swinger’s party or something?”)

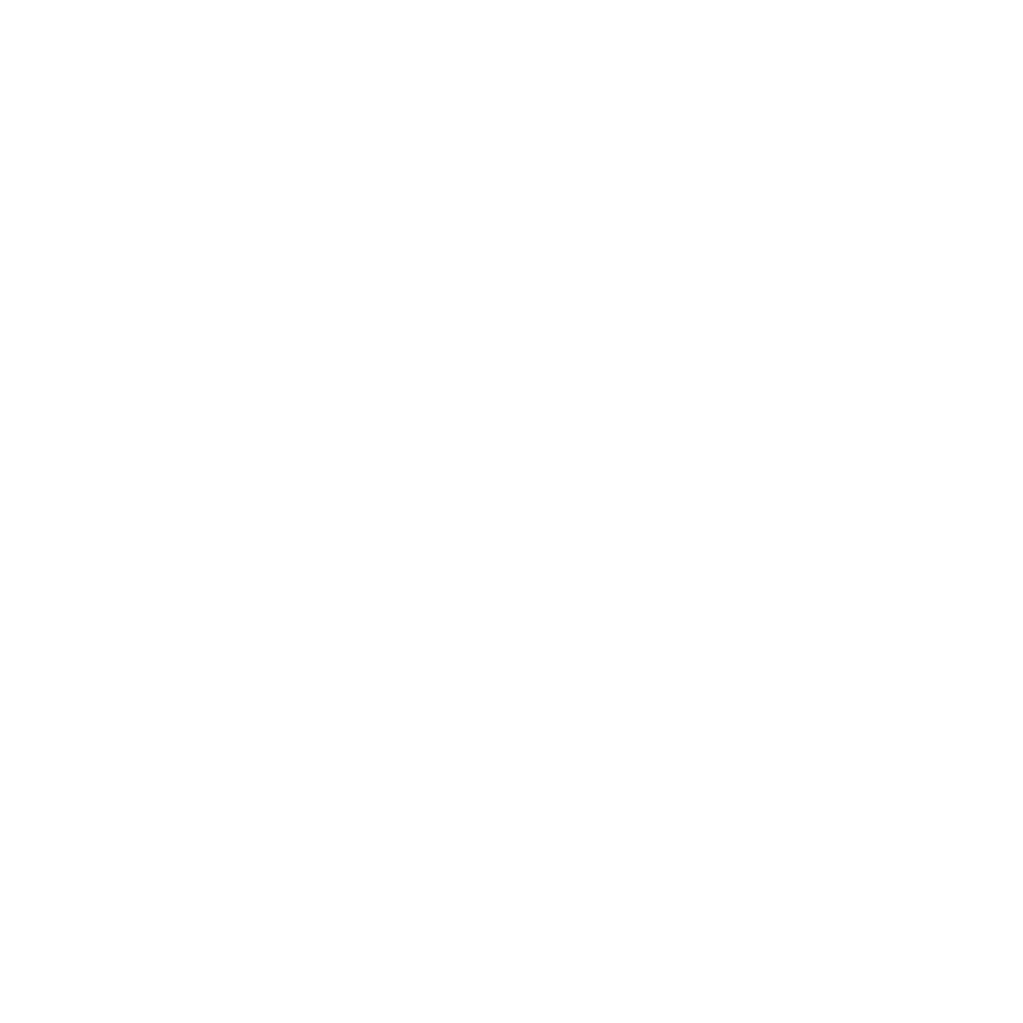

That evening, I caught myself nearly careening off a hilltop cliff after ingesting a combination of artisanal nicotine gum, a mild psychoactive flower called blue lotus, and off-brand ketamine—a woozy mix I’d miscalculated as ideal for chilling. Golden hour was draining out of the San Jacinto mountains, and I counted at least six shades of orange before my head started to spin. Scrambling on a nearby rock, I gazed around the crowd gathering to watch the sunset, and picked out familiar faces from Dimes Square parties, LA art galleries, Bushwick raves, and Discord groups. Under a charred cedar tree, a trio of musicians from the LA-based collective Floating were playing an improvised set, spinning webs of melancholy tones with a saxophone, flute, and synthesizer. The sylvan scene was beautiful—I smiled and tried not to puke.

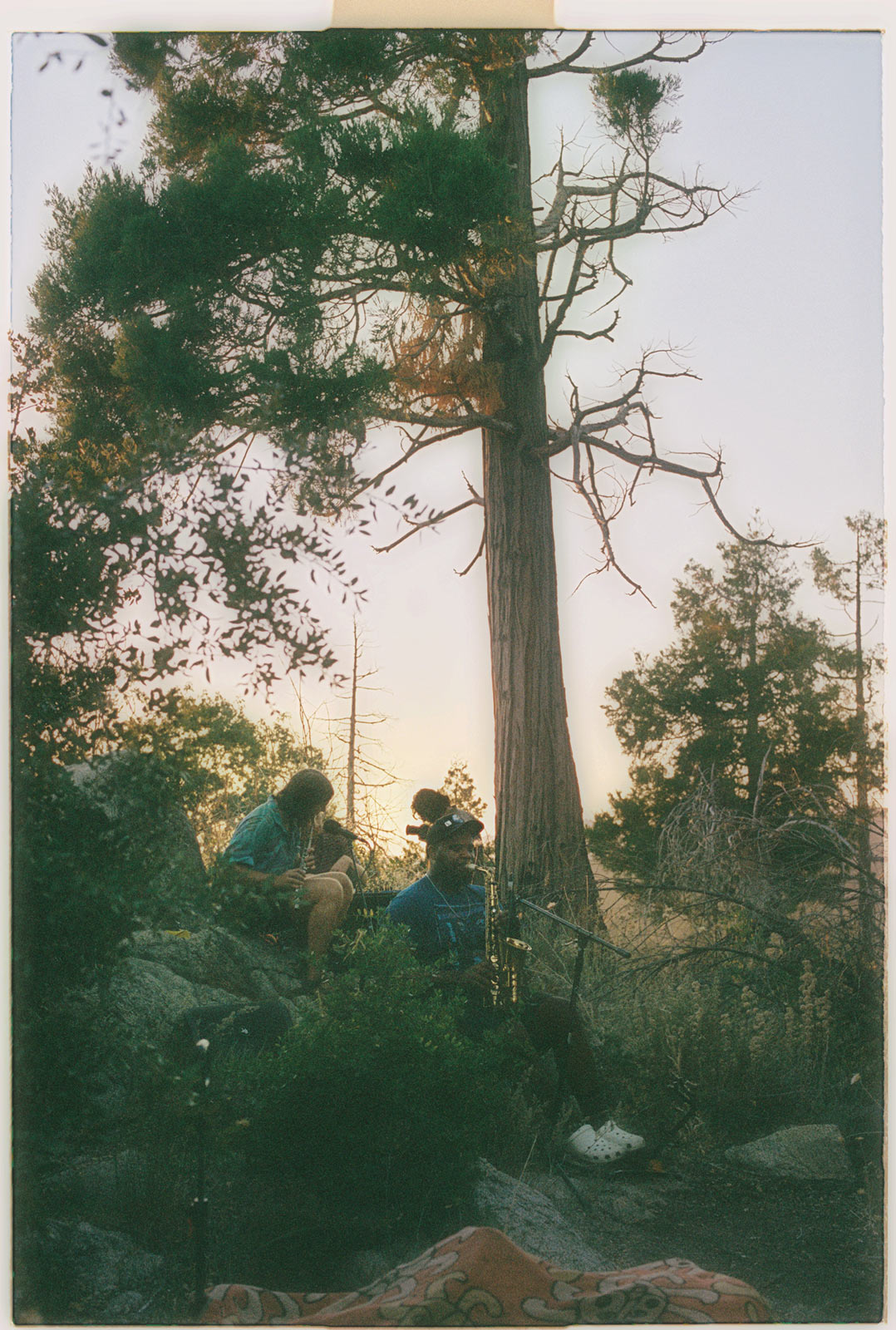

As I made my way down the hill through a forested clearing, I discovered an amphitheater stage nestled amongst the trees. Rising electroclash star The Dare— his real name is Harrison Patrick Smith—appeared to the squeals of women in the audience dressed in cottagecore dresses. “I like the girls that do drugs!” Smith howled, back arched to the sky as if making a confession to the heavens. “I love girls who like to fuck, that’s what’s up!” screamed his acolytes in a horny singalong.

One of Smith’s friends leaned in and told me that the star had been accused of being a pedophile by strangers on the internet. “It’s the kind of post-Q-Anon conspiratorial thinking that’s so popular these days,” the friend noted with a smirk, alleging that the controversy only boosted Smith’s clout.

Something about this moment felt distinctly zeitgeisty: from the music’s nostalgic fetishization of a sloppier internet era to the sex-negative online conspiracy hanging over Smith’s takedown like a mist. I couldn’t imagine these cultural touchpoints converging in any other point in history (no one ever accused the original bloghouse-era DJs of being groomers!) yet I wasn’t sure if there was a larger point here. The whole thing just felt like an eye roll.

“The revolutionary spirit of recent years has flamed out into disillusioned retreat, and the only mass movement America mustered this summer was Girl Boss feminism dressed in bimbocore Barbie pink.”

On FEST’s final night, I found myself at the “After Hours” stage—a mirrored dance studio that hosted DJ sets from 10p.m. to midnight. The night before, Charli XCX and AG Cook had played back-to-back on a muffled sound-system, everyone on the vibeless dancefloor crunching towards the front and craning their necks for a glance of the stars. Thankfully, the system had been fixed for tonight, but most people were still just standing around outside, chatting with drinks in hand as if we were at a house party. I found Daniel Keller in the crowd, a post-internet artist who’d DJ’ed a set of nightcore and old-school jumpstyle earlier that night under the moniker AIDS 3-D.

“So many subcultures these days seem to only care about escapism,” I told him. “It’s nice how this festival wants to offer solutions, even if I’m not sure what exactly those are yet.” Referencing a phrase used by art curator Shumon Basar in his lecture on lorecore earlier that day, I added, “This scene feels like the optimistic version of the dark forest theory.”

Keller looked around the crowd and nodded. “Part of it might be market optimism…” he said, referring to analyst chatter that the crypto market might be due for a bull run this year. “But yes—we need more solutions. How did we end up with this idea that ‘problematizing’ things is virtuous, but ‘solutionism’ isn’t? When did ‘solutionism’ become a dirty word?” (In the tech world, Silicon Valley’s tendency to see technology as an easy solution for the world’s problems has been labeled as “solutionism” by critics.)

Later, he sent me a chart that suggested the left is becoming the league of doomers, with more liberals than conservatives feeling hopeless and dissatisfied with their lives in the past few decades. “It’s weird because the left is supposed to be building a utopia,” he noted. “Feels like PTSD from decades of disappointment, but it’s foreclosing the possibility of a shift back towards progress.”

“The system still seems to mirror existing inequalities around wealth and power, while building a paywall around the process of creating a members-only group—something you could easily just do… without crypto.”

Maybe this is why left “counterculture” today feels so mid, like we’re all just burying our heads in ketamine. The revolutionary spirit of recent years has flamed out into disillusioned retreat, and the only mass movement America mustered this summer was Girl Boss feminism dressed in bimbocore Barbie pink. Resistance to Big Tech’s algorithmic autocracy feels futile—Twitter might be over, but we’re still stuck scrolling on TikTok and Instagram.

Friends With Benefits’ optimism might be contagious, but I’m not sure if their “solutions” are salient. Like other members-only clubs trading in social currency, significant capital is required to gain admission and receive the “benefits” the DAO’s name hints at: The more tokens you purchase, the more influence you’re able to exert over the decisions of the collective. Blockchain technology provides a nice gesture of radical transparency, I suppose, by providing a publicly-accessible ledger for these transactions. But the system still seems to mirror existing inequalities around wealth and power, while building a paywall around the process of creating a members-only group—something you could easily just do… without crypto. Perhaps the most useful benefit of joining Friends With Benefits is the ability to purchase collective clout—to be able to gain access to other members, share resources, and debut your products to a built-in audience. In other words, Friends With Benefits’ commodification of “community” might be its most brilliant move yet.

Still, there was no denying that the congenial atmosphere of the festival was contagious. “One thing ‘utopias’ do is try to rewrite the codes of human relating,” wrote someone on Raveforum, a new website for anonymous reviews on raves and like events. It might sound woo-woo, yet it’s true: With the world descending into dogshit, the institutions won’t save you—but maybe your friends will. As I headed back to my Airbnb, the bumpy shuttle ride finally dislodged the churning nausea that I’d been holding in all night. I stepped onto the parking lot, leaned forward, and spewed the content I’d ingested that day—all the bits and chunks looked vaguely familiar, yet remixed into a sludgy goo—and in the muck I saw the festival’s quivering reflection. My friends held my purse and helped me back home.