Between mulberry picking and rubbing shoulders with the art-world elite, the book finds universality within an extraordinary childhood

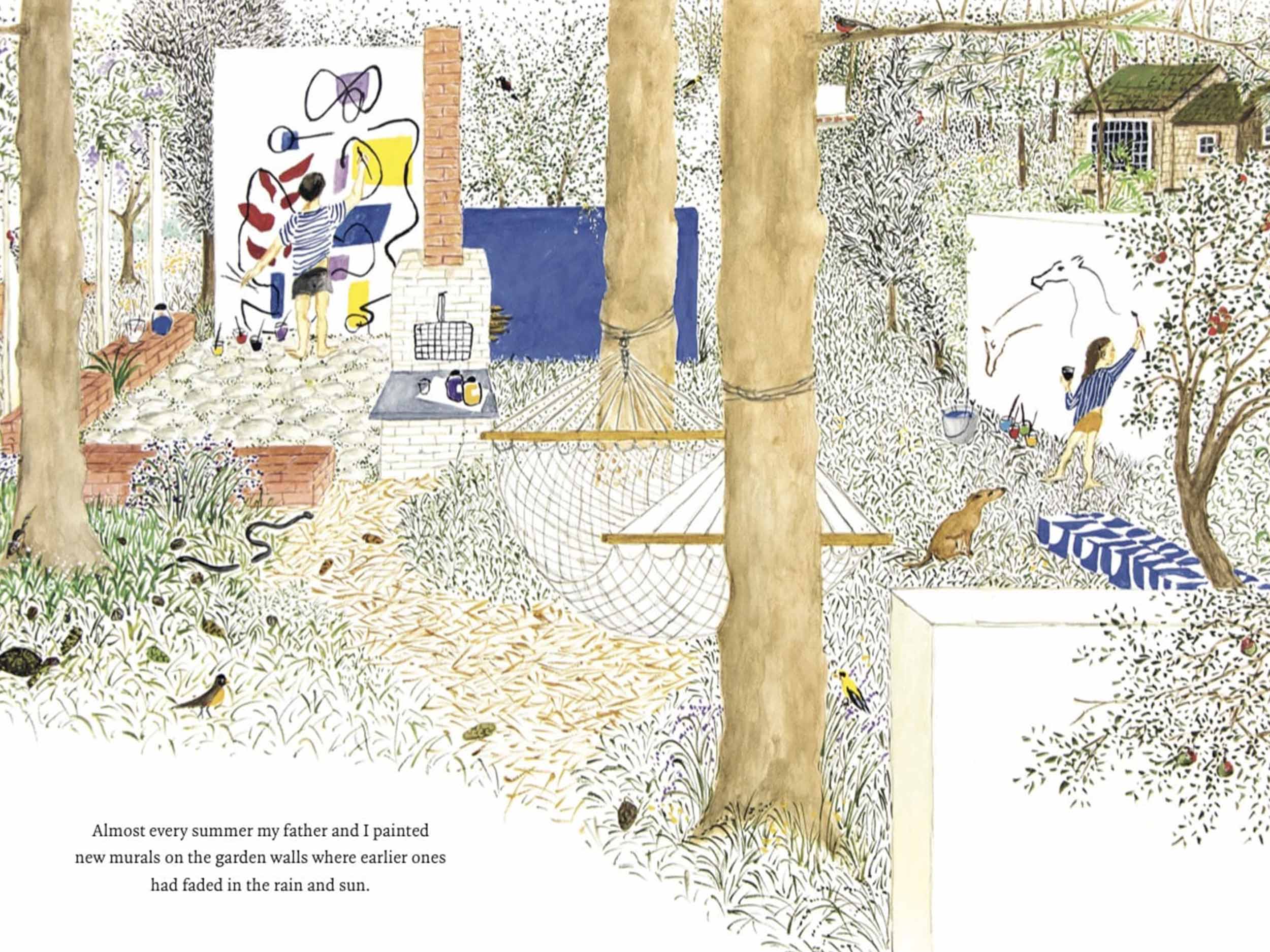

A young girl sketches on a sprawling sheet of shelf paper. The bright, intricate artwork is drawn from memory, lush images from the past streaming forth from her head.

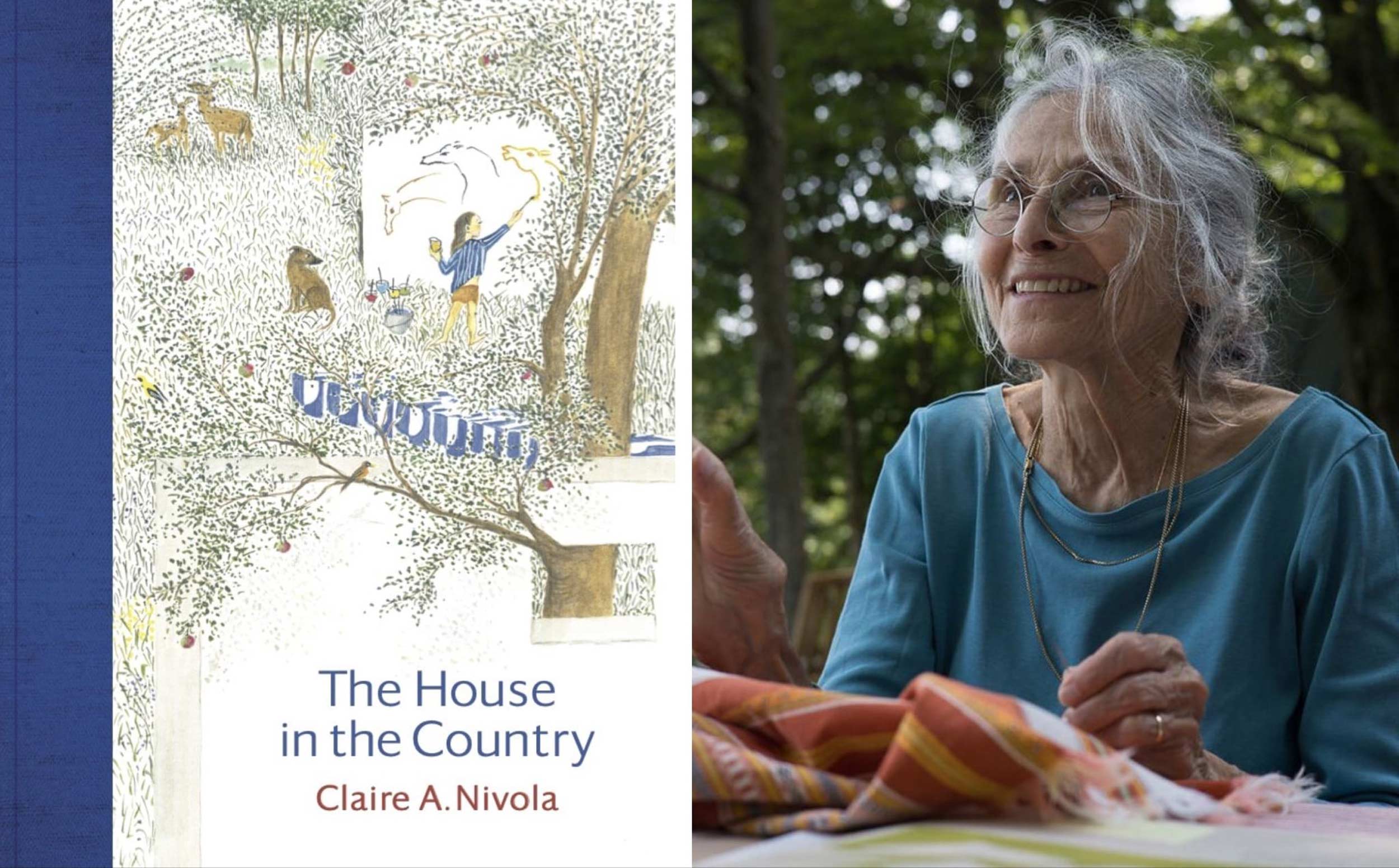

In many ways, this first scene in Claire A. Nivola’s The House in the Country is an extension of that sheet of shelf paper, unfurled to cover an entire lifetime. Nivola, who is now 75 years old, wrote and illustrated the children’s book as a way to remember her own youth. Specifically, she sought to recreate the Long Island home where she spent her summers—a bohemian estate in East Hampton that’s been frequented by artists like Marilyn Monroe, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning, all of whom were all friends of the author’s father, sculptor Costantino Nivola.

Nivola started illustrating shortly after she graduated from Harvard College in 1969. Although children are her primary readers, she believes her books resonate with a wider audience. “My feeling is, you’re not really writing for children,” she says. “When you write, you’re writing for everybody and anybody—you’re just putting it in a form [for children].”

She calls herself a minimalist by nature. “That is, I like to make a lot out of very little.” Nivola compares writing children’s books to writing poetry: the sparseness of the form forces her to economize her language, presenting new creative possibilities.

“We’re constantly figuring out our distance. I think it’s core to the childhood experience.”

The House in the Country alternates between Nivola’s subjective memories of the house—picking mulberries with her brother in the garden, riding her bicycle to the nearby bay—and an objective history of the property. She says that the more concrete details—the illustrated map of Long Island, for example, or the list of families that had previously owned the land—were inclusions made over the book’s editing process. “The way I started was entirely with the subjective,” she says. “That was the heart of what I wanted to write about—the complete subjective story of my love for this place.”

Nivola’s proximity to celebrities in her youth is perhaps the least interesting part of The House in the Country. In the book, she describes the figures who visited her house as “intruders on my private child’s world.” A young Nivola is portrayed, holding a tray of desserts during one of these star-studded dinner parties. She can only wonder: “When would they leave?”

“I didn’t even want to put in Jackson Pollock and de Kooning,” Nivola says. Although she notes that the artists were “nice” and “charming,” she also brings up their serious drinking problems. “They were just neighbors that you would sort of see, but then they became so famous that when I would mention to people, Oh, yeah, I knew Jackson Pollock, their jaws would drop and stars would come into their eyes,” Nivola recalls. “This is our celebrity culture: It glamorizes a world that isn’t glamorous.”

Strip away the star power, and The House in the Country becomes what Nivola intended it to be: a book about leaving the past behind. “[It’s] really about loss,” she says. “And it comes from this house: passed from my hands to my brother’s. I knowingly, as an adult, gave it up.”

“There’s a sense of betrayal—that I’ve betrayed this place by choosing to let my brother take it, because I could have taken it,” the author continues. “It makes the loss very painful, but it was almost something I had to do. For whatever mysterious reasons of growth and development, you have to let go of that past.”

She discusses a line from Imaginary Homelands, Salman Rushdie’s seminal essay on literature and migration. He writes: “It may be argued that the past is a country from which we have all emigrated, that its loss is part of our common humanity.” Although Nivola recognizes the parallels between the loss of her childhood home and her immigrant parents’ loss of their home country of Italy, she deigns to directly equate the two. “The difference [between me and] my parents is like the difference between, let’s say, a parent that you love [who] suddenly dies a premature death of a heart attack, and they’re just much too young and you’re not ready. Or, they die at the end of a long life—and even though it’s a terrible, sad loss, it’s within the nature of things that they would die at that age.”

“My parents’ loss was not a natural loss,” Nivola explains. Her mother was Jewish, and her father was an anti-fascist. They fled Mussolini’s rule in 1939. Nivola’s loss, which she describes as “the loss of childhood,” was more inevitable. “Everybody loses their childhood and their past,” she says.

Nivola’s treatment of acute, abstract emotions becomes tangible in her artwork. Her childhood is linked to the architecture of her house: the sunflower-colored kitchen, the uneven stucco on the walls, the murals surrounding the garden. “Place is very important to children,” she says. “Even if they don’t have a beautiful, stable home, it’s where they are, and it’s very real and intense.”

“But mainly, they’re going to be able to relate to the loss of something,” she continues. “Children are, from the beginning, attached literally to their mothers. Then we have to get a little distance. We’re constantly figuring out our distance. I think it’s core to the childhood experience.”