The TikTok trend champions imperfection, suggesting fatigue around aspirational online content and desire to find pleasure in the everyday

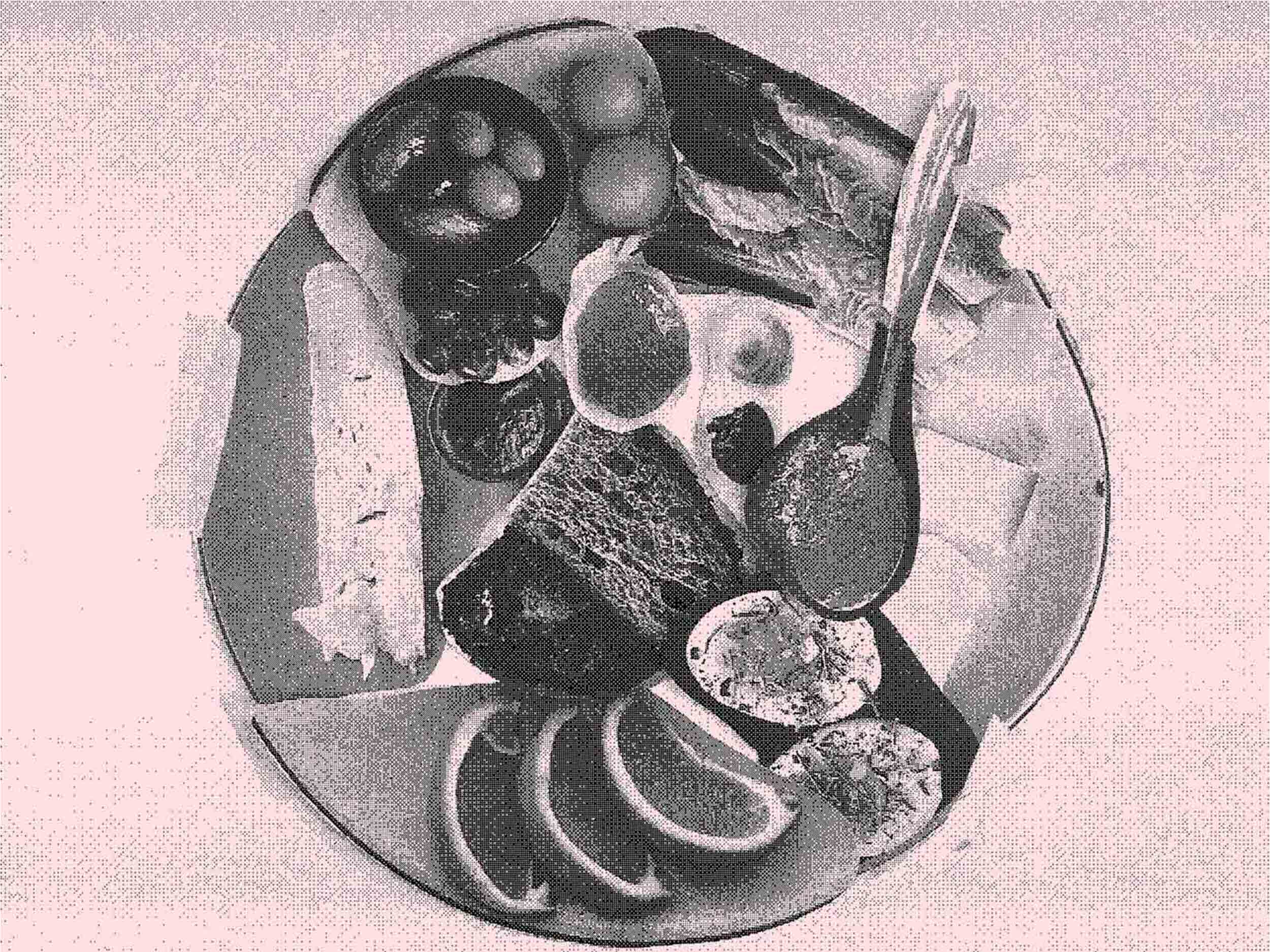

A pickle. A hunk of cheese. Cold bread. Grapes. A sleeve of fancy crackers. Some olives. A handful of almonds. A ripe peach.

These are, for the unenlightened, the makings of “girl dinner”—a social media trend in which women share videos of chaotic, low-effort snack plates they’ve assembled from a range of seemingly random ingredients. If you scroll through the countless TikTok videos on the subject, you’ll see that the actual items that compose girl dinner are functionally interchangeable; more important is the fact that it is made by one person, for one person; that it involve little in the way of prep work or dishes; and that you post it, soundtracked by its signature singsongy jingle.

Girl dinner is not the first mundane activity to receive a makeover on TikTok. Last year, the “hot girl walk” made its rounds, with a series of viral videos leading people to question what, exactly, differentiates it from the near-identical activity humans have been engaging in since they gained the ability to stand upright. As with hot girl summer—which repositioned hotness not as a physical trait, but as a vibe—what sets a hot girl walk apart is not in the eye of the beholder, but the mindset of the individual: a person ruminating on their goals, what they’re grateful for, and just how hot they are while engaging in the age-old activity of putting one foot in front of the other.

Olivia Maher, the TikToker who coined the phrase “girl dinner,” recalls being on a hot girl walk when she thought of it. A lightbulb went off in her head, and she posted a video to TikTok, flipping her phone camera to display hunks of butter and cheese, part of a baguette, a handful of pickles and grapes, and a glass of red wine. “I call this girl dinner,” she proclaims. The 15-second clip has been watched more than a million times.

Nutritionists like Kathrine Jofoed have since weighed in on what makes girl dinner so popular, suggesting that its appeal lies in the variety of flavors and textures it offers, as well as a much-needed respite from rigid notions of what food “should” be. Others argue that it’s the rebellion against feminized labor—cooking, doing dishes—that makes picking cornichons and cheese off a plate not only satisfying, but quietly revolutionary. (According to Maher, a key part of the pleasure of girl dinner is the sense that you “barely worked for it and it feels like an indulgence.”)

“Implicit in girl dinner is the rejection of the picturesque, put-together version of femininity championed by aspirational content… suggesting a declining interest in wellness trends that revolve around the labor of self-optimization.”

Such styles of eating are, of course, not particular to girls—and since the trend took off, many have pointed out that it resembles a range of snacks found around the globe, from Spanish-style tapas to Mediterranean mezze platters. “Most Germans eat like this every evening. We call it Abendbrot,” tweeted the writer Tom Hillenbrand. Nigella Lawson, and a slew of TikTok commenters from across the pond, agreed—adding that such snack plates are common in the UK, where they’re called “picky bits.” Then there’s the “ploughman’s lunch,” a deconstructed sandwich commonly served to British tradespeople, or the “bachelor’s handbag,” a common snack in Australia consisting of rotisserie chicken, bread, and other sides.

What makes girl dinner fundamentally different from an everyday snack is the act of posting it, in all its messy glory. Implicit in girl dinner is the rejection of the picturesque, put-together version of femininity championed by aspirational content—combatting the rhetoric of hustle culture, and suggesting a declining interest in wellness trends that revolve around the labor of self-optimization. (Think of the that girl morning routine, consisting of 5 a.m. wakeups, smoothie bowls, bullet journaling, meditation, and comprehensive skincare routines.)

It makes sense that people would swing in the other direction after being sold such impossible ideals—relieved to learn that others are, unbeknownst to them, engaging in similar thought patterns and activities. According to girl dinner’s early adopters, this is a key part of the trend’s appeal. “There was this feeling of, Oh my God, I’m not the only one,” says food content creator Alana Laverty. “I love anything that celebrates something women are all doing, but we don’t all know that we’re doing it.”

If you have the instinct to make fun of such micro-trends, as I initially did, I’m going to level with you: I understand the urge, especially at a time when every aesthetic under the sun has been rebranded, subverted, and reified to the brink of meaninglessness. I, too, never want to hear the words “vanilla girl” again! But it’s worth remembering that the women bonding over their meals are not asking to be covered by the New York Times; they’re just attempting to find pleasure in the everyday, a logical conclusion of TikTok’s mandate that people “romanticize their lives.”

Girl dinner may not be reinventing the wheel—but it’s a refreshing break from trends that function by making people feel inadequate, and encourage much less sustainable forms of consumption. After all, a snack plate by any other name would taste as sweet (and as salty, and as crunchy.) But would the act of eating it be a source of bonding, and—dare I say—fun?