Amid the crowds of the kilo sale, Shahidha Bari bears witness to the perennial art of passing down and picking up

The Round Chapel—a horseshoe-shaped building in the London Borough of Hackney—is accustomed to keen congregations on Sundays. Built in 1871 as a nonconformist church for dissenting worshippers, its grounds have long been deconsecrated. These days, it’s a trendy venue for hipster weddings and pop-up crafts fairs whose probiotic juices and artisanal candles regularly attract crowds of chattering young things. I arrive there on a Sunday in February, joining the crowds gathered for the eagerly anticipated “kilo sale” that day. “You need a ticket,” a woman in the queue informs me sympathetically, noticing my cluelessness and pointing to the QR entry code on her phone. I glance at her, and I am confused—not about the entry requirements, but because she’s young, a teenager, wearing bootcut jeans and an oversized rugby shirt. It’s a familiar preppy look that I recognize immediately from the mid-’90s, and it takes me a moment to register the irony with which she intends it.

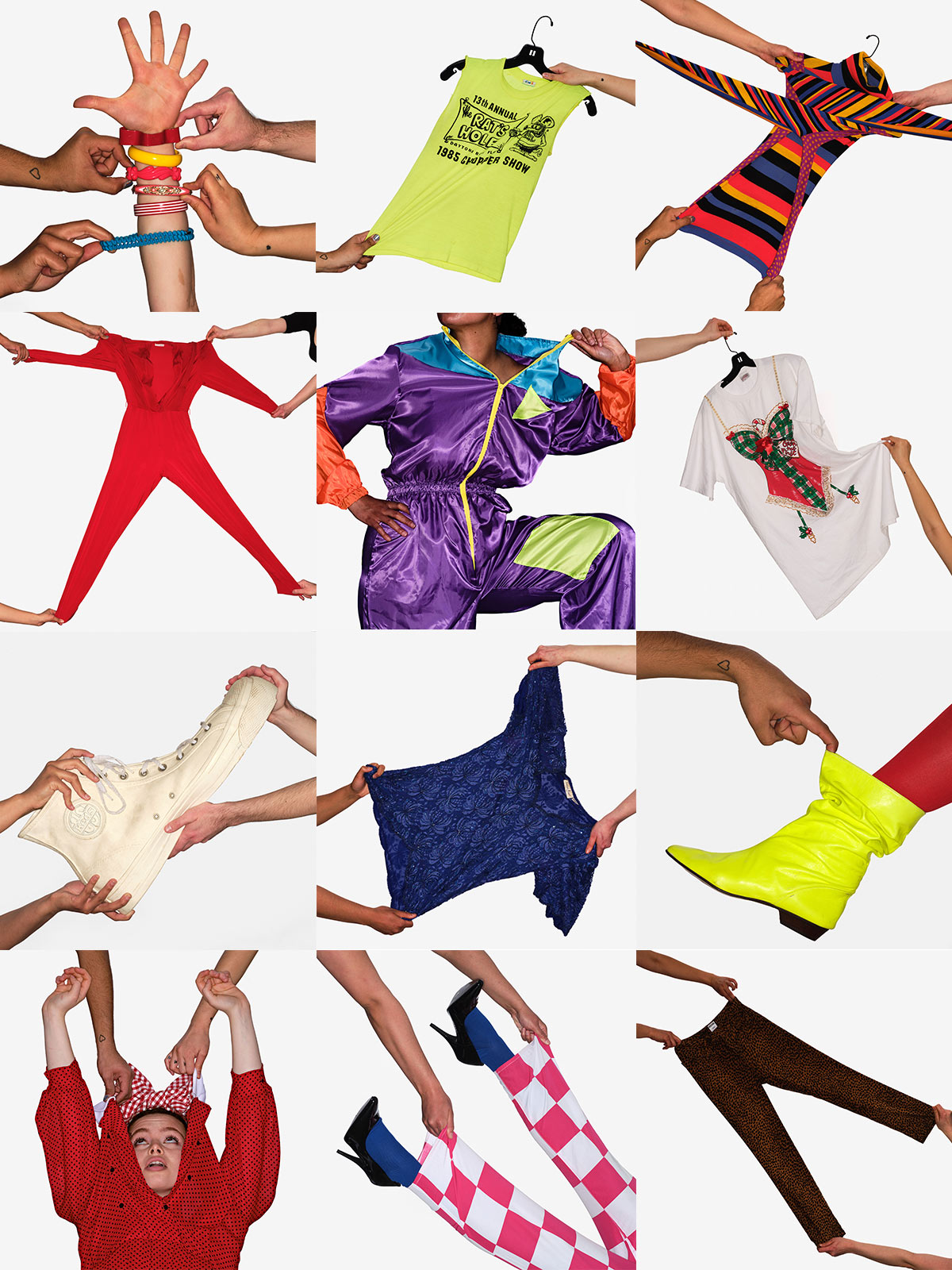

The queue comprises around a dozen young people: ragtag and bohemian, with big mohair coats and trailing scarves, faces freshly scrubbed or marked with the vague mascara trail of the night before. They are a change, certainly, from the earnest worshippers who once frequented the chapel, but these visitors are no less fervent in their ministrations. They arrive punctually, clutching empty tote bags, and queue faithfully. When the doors open, they’ll be met with a divine sight: rails and rails of secondhand clothing. Under the chapel’s lofty ceilings and intricate iron latticework, rows of hangers are haphazardly arranged, with clothes as bright as candy wrappers dangling from them. I purchase a ticket and climb up into the gallery to watch the frenzy unfold below. This, I think, settling down, is what we mean by the spirit of the age. Here is the heart of this city.

I like to imagine the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, who lived to witness the first part of the 20th century, might have agreed with me. “An arcade,” he observed, “is a city, a world in miniature.” His Arcades Project, which began in 1927, was a kind of card catalog compiled from his reflections and observations as a flâneur meandering through the 19th-century shopping arcades of Paris. All of life, he thought, could be found in the cafés, repair shops, brothels, and boutiques housed in these bustling indoor boulevards shielded by a glass roof. Benjamin was convinced that capturing the culture of the arcades would be the key to understanding modernity from the ground up. To uncover the life of the arcades would be to bestow a “prince’s kiss,” a magical act that would reveal everything about the nature of capitalism and consumption. It might also, he thought, illuminate something mysterious about the nature of commodities, the stuff that we desire, and the relationships they forge between us. What, I wonder, does it say about our times that the stuff young people desire is secondhand?

A kilo sale is a pop-up market where secondhand, vintage, or used clothing is piled high (or arranged along the length of a groaning rail) for miscellaneous hands to rifle through. When the doors open at 10 a.m., the crowds rush in, expertly eyeing their way to the good stuff and politely elbowing their way to the checkout, where their items will be weighed and priced by the kilo. This accounts for the empty tote bags wielded by the young people in the queue—you do well to come armed.

I peer down and assemble a mental inventory: a Super Mario Brothers t-shirt faded over the years, a polyester shell suit that looks as if it audibly crinkles to the touch, a denim blazer with double patch pockets, a jewel-colored velvet jacket worn at the cuffs, a floral cotton skirt visibly softened by so many washes, several football shirts from teams now fallen out of favor, tank tops, bell bottoms, distressed jeans, suit pants with neatly pressed front pleats, an Aran knit sweater, a cable-knit cardigan, a boyfriend coat, dozens of crop tops, a pair of spotless high-tops, and a sadly scuffed tennis shoe cast in among the medley.

“I’m inclined to think that there is something really important about the secondhandedness of the secondhand: the idea of a material form of transmission, a garment that literally passes through many hands before it reaches our own.”

Later, when the crowd thins and I venture downstairs to tiptoe through the debris, I inspect the labels. There are garments from all the classic British High Street stores, some vintage and long forgotten, many simply felled in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007: the classic St Michael label of Marks & Spencer; the now-defunct Debenhams; the homely C&A, BHS, and Littlewoods stores of my childhood, popping up again like tiny specters. It feels like a resurrection of sorts to see these names, so unloved for so long, outgunned by the big fast fashion stores and online brands, now eagerly snatched up by stylish young people. At the back of the chapel, the bronze pipes of the 19th-century organ tower benignly over the scene. I start to think that something incalculably precious was lost with the demise of those familiar old stores, and what I’m witnessing here is a quiet revolution. For all our anxieties about fast fashion and the thoughtlessly acquisitional impulses of Gen Z consumers, lured by trends on social media and cheap online retailers, here I see them determinedly leading a counter-movement, pursuing a different economy of clothes. They are unpersuaded by homogenous notions of the “fashionable.” Here, they hungrily seek out something utterly idiosyncratic. And they prize the old, unseduced by the relentlessly new.

Recently, kilo sales have become commonplace in this city. In the weeks after Hackney, they are scheduled for a church hall in Camden and a shipping container pop-up in Brixton. How should we read this phenomenon? The resourcefulness of young people looking for cheap clothing in an economic downturn? Yes. An increasingly voracious appetite among the young for sustainable forms of consumption? Almost certainly. And adjacent to that, a deeper sense, perhaps, that something is profoundly amiss—immoral even—about the cultures of fast, disposable fashion on which the garment industry has thrived for so long. The data is straightforward: Fashion, a global industry worth $2.4 trillion a year, accounts for nearly 20 percent of industrial water pollution and 10 percent of carbon emissions. Of more than 100 billion items of clothing produced each year, 20 percent will go unsold, to landfill or incineration.

Yet trips to the chazza (as charity shops are fondly known these days) are no longer occasions of embarrassment, but Instagrammable field excursions with influencers dedicated to sharing their “hauls” on TikTok. If High Street brands are alarmed by this apparent backlash to the brand-new, they’re not showing it. Instead, they are ever agile, audaciously co-opting this trend like any other by curating their own, often wildly overpriced “pre-loved” rails. Secondhand has not only become mainstream, it’s de rigueur. This season’s London Fashion Week opened with a secondhand clothes show, titled Oxfam Fashion Fighting Poverty, curated by British stylist Bay Garnett—who famously dressed Kate Moss in vintage finds for British Vogue in 2003.

Online, some influencers swear by pre-loved and others proclaim the merits of vintage, but the distinctions between these apparent categories of secondhand clothing are semantic rather than properly taxonomic. For my own part, I’m inclined to think that there is something really important about the secondhandedness of the secondhand: the idea of a material form of transmission, a garment that literally passes through many hands before it reaches our own. Handing down clothes, of course, is no new phenomenon. Clothes in the Middle Ages, for instance, were often passed, as it were, from master to servant, between adult and child. Historically, the cost of materials and tailoring labor meant that clothes, even everyday ones, were more prized than they often are now. Their value meant that they could not simply be discarded. In fact, you can read the economic history of clothes in the psychogeography of London itself. You can even walk it.

From the early 18th century onward, secondhand clothing stalls emerged across London, in both East and West Ends. Their purpose was largely to clothe the poor, but they also served an emergent middle class. Secondhand clothes dealers were often skilled tailors, their goods sourced from servants who had inherited the discarded clothing of their wealthy employers. Such garments were not often suitable for their stations in life, but they could be sold profitably. The garments would, in turn, be purchased by an aspirational, upwardly mobile urban merchant class, keen to mimic the dress styles of the affluent. You might call the whole thing an early form of “influencing.”

“It is life, not death, you find amid the crowds of a kilo sale. The selling, buying, and bartering of clothes was—and remains—formative to London and the communities forged within the city.”

In Britain, the industrialization of the 19th century, the mass importation of fabrics and emergence of cheaper fabrication processes allowed for the greater affordability of new clothes. Even so, the secondhand trade remained an essential means of clothing for the poor, albeit with an additional stigma now. This shift in attitude is illustrated by Charles Dickens when he observed in 1836 that wandering the secondhand clothes market of Monmouth Street near Covent Garden was akin “to walk[ing] among these extensive groves of the illustrious dead.” The clothes were, to his mind, distastefully ghoulish: “a deceased coat, then a dead pair of trousers, and anon the mortal remains of a gaudy waistcoat.” To peruse the Monmouth Street market was tantamount to picking over a corpse. Over a century earlier, the poet John Gay mapped the city’s various markets, delightfully listing how “Thames Street gives cheeses, Covent Garden fruits, Moorfields old books, and Monmouth Street old suits,” but when Dickens arrives there, he finds the secondhand clothing market a graveyard.

And yet, it is life, not death, you find amid the crowds of a kilo sale. The selling, buying, and bartering of clothes was—and remains—formative to London and the communities forged within the city. Walk south for an hour from the Round Chapel in Hackney, and you’ll find yourself in Spitalfields, in the heart of London’s East End. Spitalfields has been at the center of the city’s “rag trade” for over 250 years. It has been the entry point into London for successive generations of migrants, beginning with the Huguenot refugees fleeing 18th-century France, whose proficiency in weaving helped establish the East End as a clothing manufacturing hub. The traces of their success are visible to this day in the (now highly desirable) tall townhouses they built in the area—the window height and lofty ceilings designed to maximize light so weavers could work long days. In the 19th century, persecuted Jews escaping Russian pogroms settled in the Spitalfields, finding work in the rag trade. Later came the Bangladesh Muslims in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, providing labor for pattern cutting and machine sewing for mass-produced designs. In recent decades, the outsourcing of production to international labor markets, especially to China, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, has marked the end of the manufacturing of clothes in the East End. But the rag trade is still visible in other ways, like the endless bartering you’ll find at “Petticoat Lane” on the intersection of Middlesex and Wentworth Streets. The street market there has been in existence since 1608. The original name, “Peticote Lane,” derived apparently not from the sale of petticoats, but from the area’s early association with sex work—and the rumor that, should you risk a visit, you’d soon discover “they would steal your petticoat at one end of the market and sell it back to you at the other.”

All of this is to say that the sharp-elbowed women stuffing Super Mario Brothers t-shirts into tote bags on a Sunday morning in the Round Chapel are part of an ongoing story about the life of this city. The making and selling of clothes have ebbed and flowed with successive generations of newcomers, and each has left its indelible mark on London. The old cavernous textile warehouses along Commercial Street might now be refurbished loft living spaces, but the dazzling Asian sari shops with their elegantly draped mannequins in full sequinned glory still hold court all the way along Whitechapel Road. In between the luxury living and endless espresso bars, there are haberdasheries, vintage clothing shops, and old-fashioned tailors in dilapidated dry cleaners, still carving out a living with their needles and threads.

COVID, people complain, made us forget how to wear clothes. For two and a half years, our smart shoes gathered dust and our suits slumped on hangers as we slouched in comfies. We have been wary of unsanitized touch, our hands kept safely to ourselves for so long. But here I am, waking up again in a city that has always loved dressing up, watching young people happily riffling through clothes that have often enough been in the world longer than they have. They are unafraid, making independent choices about how they want to look, conscious of where their clothes have come from. At the Round Chapel, a boyish young man in a long leather trench coat judiciously rubs the edge of a suede jacket between his thumb and forefinger. A girl in purple dungarees strokes a pink angora jumper with a flattened palm. I find my place among them, reaching to run my hands along the clothes—the cotton, the corduroy, satins, silks, distressed denim, and washable polyesters—rail after glorious rail.