Between the Pines and Cherry Grove rests a legacy of gay desire, treading nature and artifice off Long Island’s South Shore

In an early scene in Matthew Lopez’s 2018 play The Inheritance, a gay couple is struggling in the bedroom. “Think of something sexy,” one of them says in an attempt to get his partner in the mood. “Remember that time on Fire Island that we watched those two guys fucking in the Meat Rack?” he asks. “I wish we’d done that.” This visualization does the job, tipping over into longing as the memory of past voyeurism gives way to a fantasy of participation. Fire Island, that storied spit of land off Long Island’s South Shore, is both real and mythic; it’s a destination that is accessible from the city (by train, another train, bus, and then ferry), but also a projection of an idyll where queer people can love freely. As such, the island has long served as a space where memory and fantasy meet, providing imaginative fodder for visions of a sex life that is simultaneously chic and transgressive. The Meat Rack is its ground zero.

While in American slang, “meat rack” refers generally to a place full of sexually available bodies, on Fire Island, it’s a fleshy cornucopia par excellence. Located between the island’s famous queer communities—Cherry Grove to the west, the Pines to the east—this thickly wooded area is for hardcore and sometimes democratized cruising. Status is shed along with clothes, and anonymous orgies and hook-ups take place among the bushes and thickets. It has been a constant in the island’s queer history, beginning as a movable feast in ’40s Cherry Grove, shifting between boardwalks each night. Raids by local police were frequent in the ’50s—the Meat Rack has historically functioned as a political battleground of sorts. Whatever else has changed on the island, “nothing has changed in the bushes […] the bushes were always there,” writes the erotic filmmaker Peter de Rome, recalling his weekends on Fire Island in the late ’50s. “[You] could always stagger off the boardwalk and fall into the poison ivy on your way to the meatrack to round off another Saturday night on the island.”

Like the beach, the Meat Rack is one of the island’s primal scenes of desire—a seemingly timeless fact of its landscape, where sex and nature meet. It is regularly used as a location in gay porn—“Fire Island Meat Rack orgy” is its own subgenre. But the island’s manmade constructions—its architectural marvels—are equally important to its legacy as a site of sexual fantasy. Today, numerous adult performers and content creators make use of Fire Island residences to shoot content for subscription sites. Whether it’s pool decks in the Pines or rooms in the kitschy Belvedere Hotel, the island setting lends erotic content a sense of luxury and escapism, a particular vision of the good life. The basis of much pornography is rooted in a balance between the real and the idealized. Some of the most compelling examples of Fire Island on screen belong to an earlier pornographic tradition, from the late ’60s and early ’70s—the pre-AIDS era of burgeoning liberation, a time that can be readily idealized in nostalgic accounts of the past. A series of films created around this cultural juncture, including those of de Rome, shaped a visual erotics of Fire Island’s mirrors and surfaces. These images were utopian, yet aspirational—a reminder of the way that fantasy is something that can be bought and sold.

In the lead-up to its opening, ads for Wakefield Poole’s 1971 film Boys in the Sand ran in the New York Times and Variety, teasing mentions of an all-male cast. Talk of it spread in bars and at holiday parties, and when it opened that December, the 55th Street Playhouse was packed. But the commercial success and cultural impact of this “fuck film” were hardly predetermined. It could have been just another porno to play on loop with little fanfare, like many of the gay adult films that played in Midtown porn theaters at the time—only half-watched by a distracted, cruising audience. Instead, this woozy, feature-length reverie of idealized sex proved to be a crossover hit with gay and straight audiences alike. Costing around $4,000 to produce, the film made $26,000 in its first week, received celebratory reviews in mainstream publications, and made a star of its lead, Casey Donovan.

The heady visuals flickering on the screen of the Playhouse that winter represented a brave new world of sex positivity and erotic freedom—the windfall, it seemed, of the gay liberation movement, and its imperative to banish shame and come out. The film belongs to a category film studies scholar Ryan Powell calls “liberation porn,” a mode of gay ’70s cinema that was “utopian in that it sought new futures,” but also proposed “a continuum of imagination and actualization, offering trial utopias to be experimented with.” Fire Island was one such trial location, and Boys in the Sand made full use of it. The first scene shows a man (played by Poole’s partner, Peter Fisk) having sex in the Meat Rack with Donovan, who mysteriously appeared in the waters of the bay and waded inland.

Later on, the film captures Donovan by the swimming pool of one of the Pines’s distinctive modernist houses. The setting is more akin to a David Hockney painting than that of a typical porno. And there’s a twist: Donovan’s character doesn’t meet his partner the usual way, by cruising him on the boardwalk, or at the Meat Rack, or at the afternoon tea dance held in the bars at the Pines Harbor. Instead, he conjures him up from a special mail-order pill capsule, which he saw advertised in a gay newspaper. When it arrives, he throws it into the pool, and a broad-shouldered, Italian-American man (played by Danny Di Cioccio) rises from the bubbling water—a moment that got a laugh from the film’s earliest audiences. In this scene of poolside fucking, the seemingly futuristic aspects of erotic life carry small-town charm, facilitated by ads in the local paper and the magic of postal service; there’s the neat observation that Fire Island is a place where sexual fantasies are often transactional. By extension, hustlers and variously employed houseboys have long frequented Fire Island, a fact Andy Warhol dramatizes in his elliptical 1965 film My Hustler, shot in a house in Cherry Grove. In it, a gay man competes for the attentions of a male hustler, played by Paul America, who he has hired for the weekend.

De Rome described Boys in the Sand as “probably” one of the first instances of “porn plagiarism,” because of the similarities between the film’s final segment—in which Donovan has sex with a telephone line repairman he first sees from the window of the house—and his own 1969 short, Double Exposure. The visual parallels are striking; the two films are shot in the same house, and Double Exposure—which depicts a man walking along the boardwalk who spots his double in the window, naked and ready, and ventures inside to see more—introduces the motif of the erotic gaze in relation to the house’s glass surfaces. In the credits for his feature-length medley, The Erotic Films of Peter de Rome, shown in cinemas in 1973, Double Exposure is listed with the disclaimer that “it was made in 1969, & should not be confused with Boys in the Sand, made two years later.” De Rome’s digs at Poole speak not only to a conversation about originality and infringement—which emerges clearly enough in seeing the films side by side—but also to a more profound issue around desire and fantasy being inherently imitative, often born of archetypes, shared and replicated across minds and bodies. He first came up with the idea of the passerby and his naked double during a thunderstorm one night, when he was alone in the Pines house. And while his influence on Poole’s film was never credited, there is something curiously affecting about the notion that his own authorial signature—a private vision that emerged from his unique experience of the house—came to mediate Poole’s own cinematic desires in the same location.

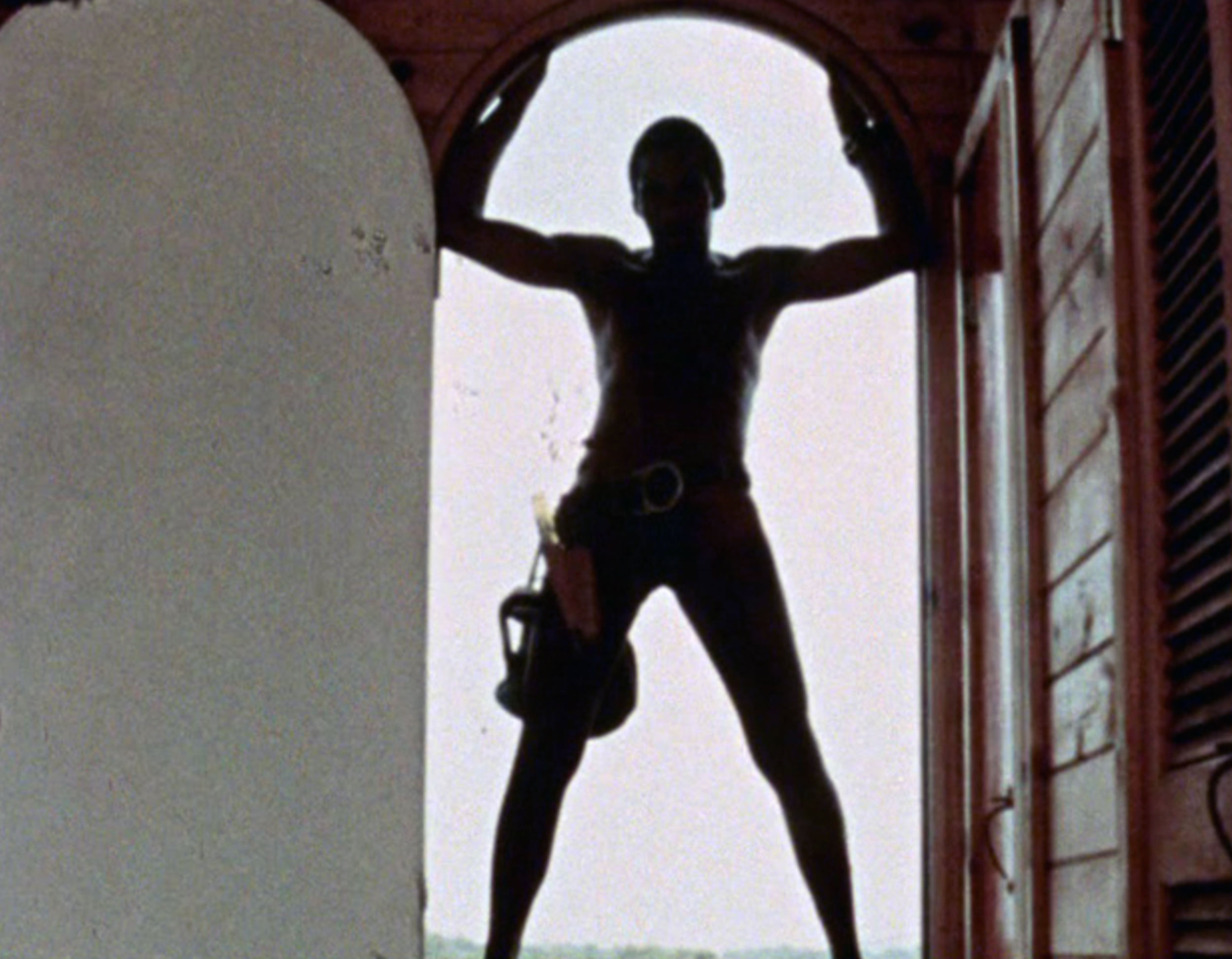

Indeed, there was a deeply personal aspect to much of the gay pornographic filmmaking of this period. De Rome’s other island film, The Fire Island Kids (1970), took shape almost by commission, when a request came in from two “attractive blond young men who had just fallen in love and wished to have their friendship commemorated on film.” They were staying at 556 Ocean Walk, a Pines house owned by Warner Brothers PR executive Stuart Roeder. Horace Gifford had reworked the house, architect Christopher Rawlins observes in his book Fire Island Modernist, by sheathing the “original dowdy square cottage” in a “dynamic diagonal wrap that gyrated towards the Meat Rack,” as if oriented in homage to the pleasures it was designed to accommodate. The fur-lined “Makeout Loft” at the top of the house was a nod to the animal and a “high perch for base desires,” where, Rawlins notes, “form follows foreplay.” Both the house and the film feel like artworks emblematic of the period’s sexual freedoms—its sense of bounty and potential. The house, de Rome remembers, “provided a wonderful background for these two young lovers and their idyllic day at the beach”—although it is tempting to go even further and invoke the cliché of a place as a character in itself. The house’s architecture is not merely a decorative backdrop; the lovers’ pleasures and desires are choreographed according to its various levels and vantage points. Gifford’s architecture, as Rawlins argues, could be its own form of seduction.

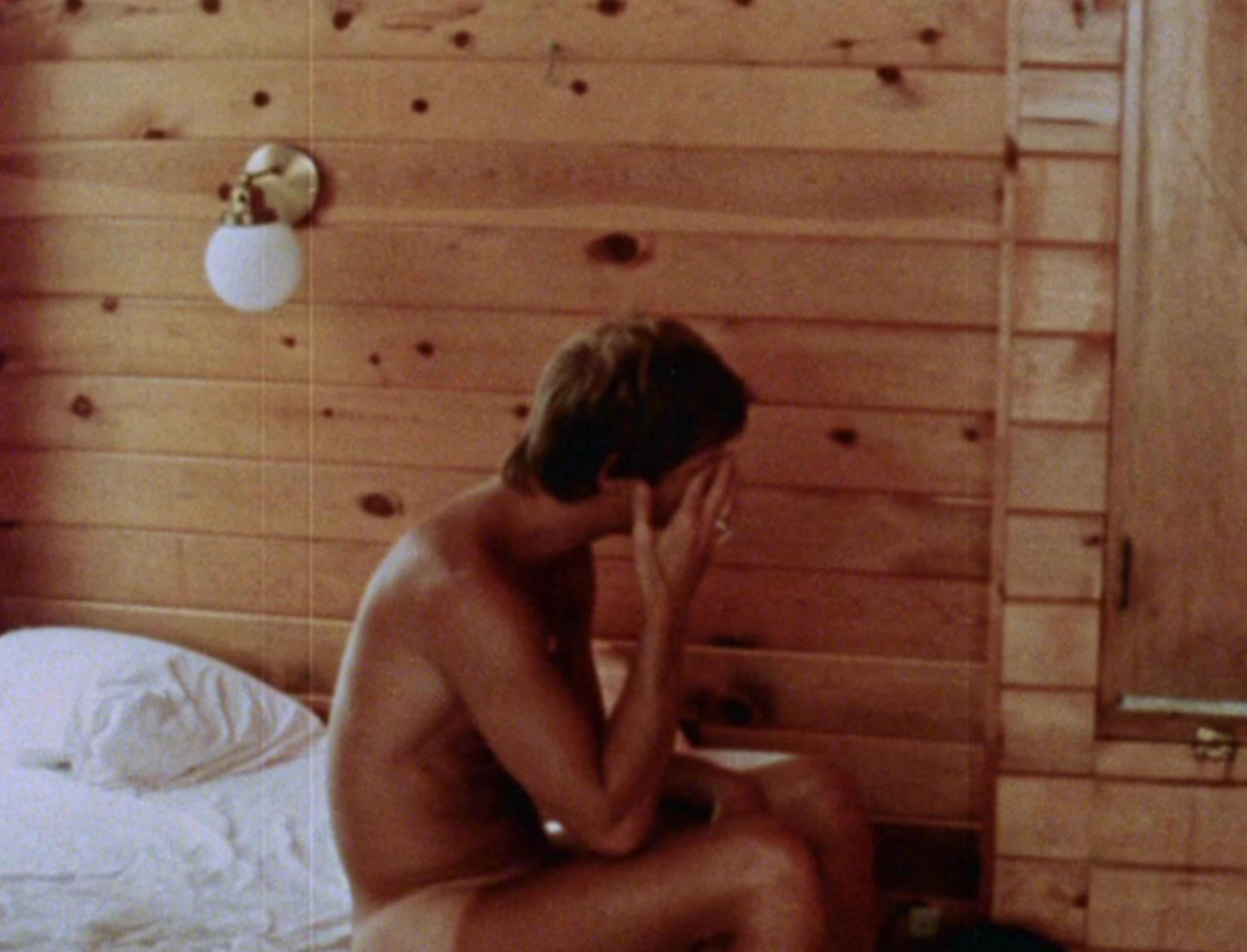

Another film from the era, Christopher Larkin’s A Very Natural Thing (1974), also used a Pines residence to tell the story of a gay couple playing house; although, in this case, the house is rather more populated—a house share—and the scene less harmonious. The couple’s trip to Fire Island follows a tense conversation back in the city, in which they discuss monogamy—one of them for and the other against—and their visit to the Pines as an attempt at “experimenting.” In the dimly-lit living space of a Pines house, the couple joins a naked orgy on the sheepskin rug, although the more traditional of the two is spooked before long and leaves the mass of writhing bodies. More softcore than hard, and more mainstream in tenor than de Rome’s and Poole’s films (which sit at the nexus of porn and avant-garde), A Very Natural Thing explores the reality behind the dream—its orgiastic fantasy is given real narrative context, in the form of a gay couple reckoning with the complexities of liberation from traditional values. But all of these films from the ’70s ultimately look to celebrate the naturalness of gay desire, their scenes of sexual intimacy housed in shining aesthetic structures that are beacons of imagined freedoms. Like Fire Island itself, they place nature and artifice in dialogue.