Journey Streams reflects on ‘I Could Not Believe It,’ the artist’s 1979 diary archiving the complex landscape of adolescent Black queerness

In 2016, I met the man of my dreams. He was bookish and kind, and he smelled like something vile and divine. He was twice my height and twice my age.

With him, I found answers to questions I did not yet know to ask—shirking my high school curriculum for new lessons in pleasure. He was one of many such connections over the course of my LA adolescence, but the only one who remains a friend. An uncertain shame clouded my memories, as I would attempt to discern where the romance ended, and where a different story began. It wasn’t until I read the words of a 14-year-old Sean DeLear that I understood my then-self as I do now.

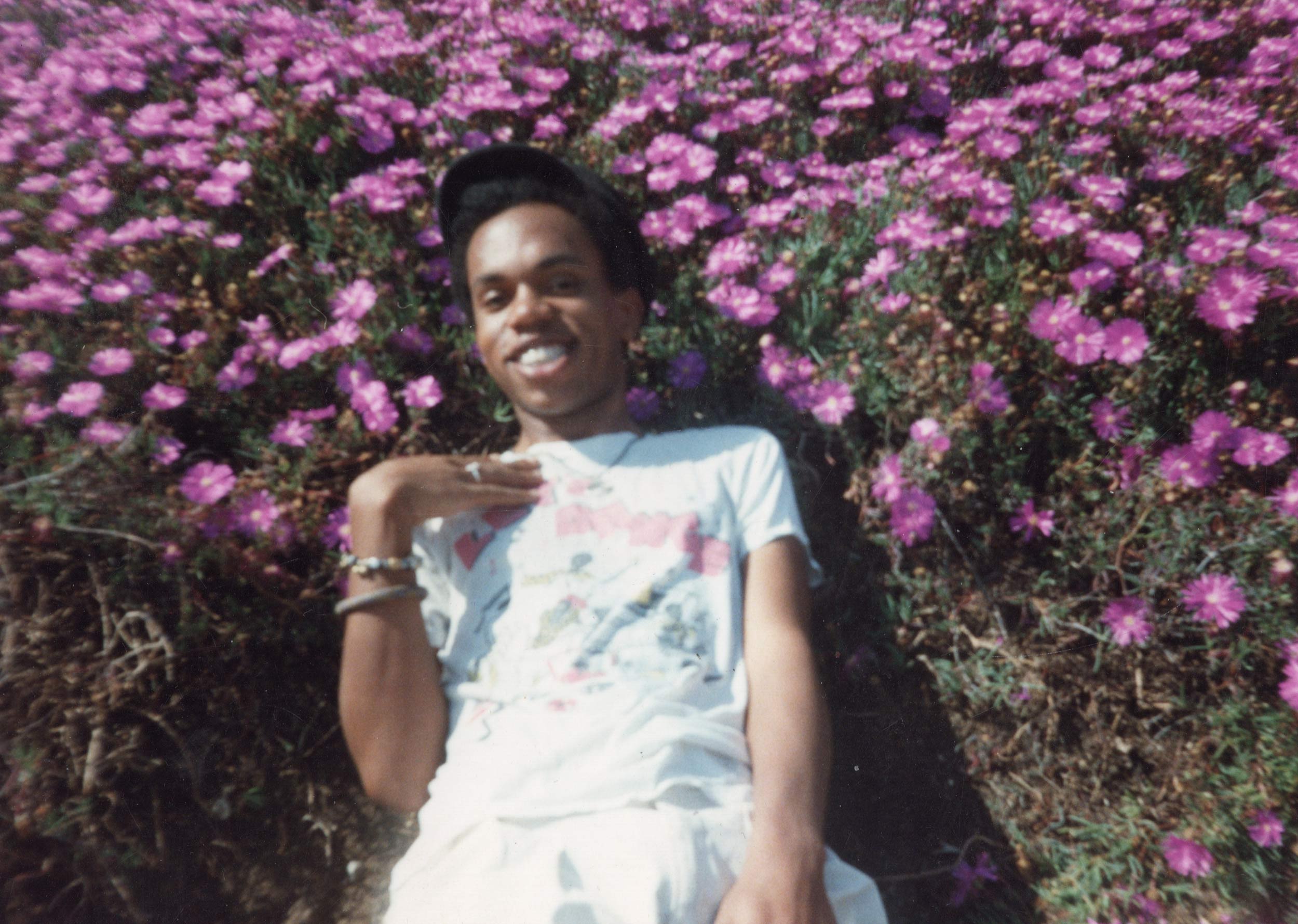

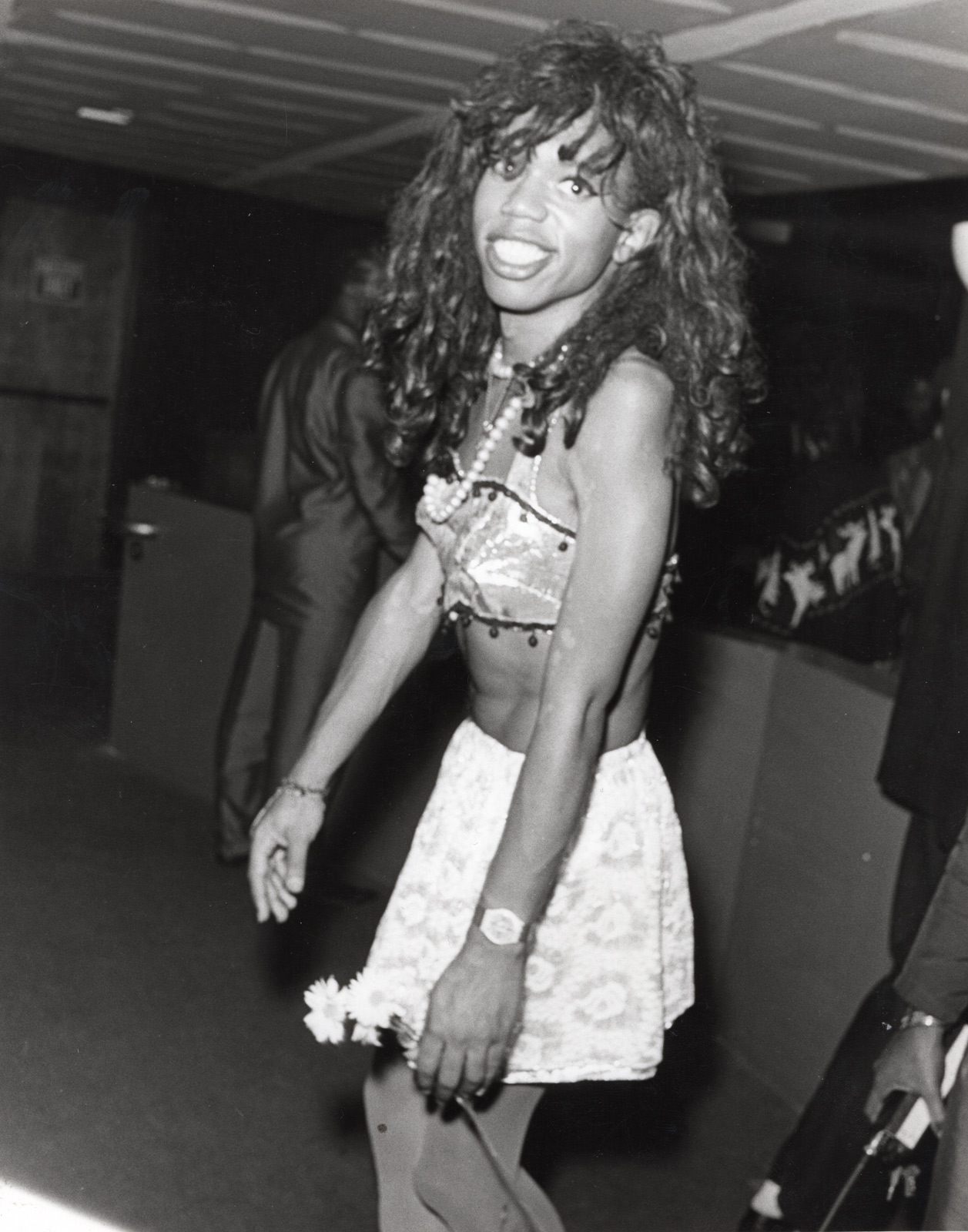

Sean DeLear’s legacy as a Los Angeles punk icon, muse, and international sensation precedes her in life and death. The magnetism of her spirit was a gift to those lucky enough to have known her. For those who didn’t, she wastes no time in introducing herself: “I am Black, have a nice bod, am doing ok in school except in English. My cock is about nine inches long and I love it.”

The diary—today titled I Could Not Believe It—is bound with the particular knowing that DeLear’s precocity demanded. Through her already-realized libido, she prophesied a desire within myself that did not wait to make itself known. Some queer people are born into particular circumstances that require treading the sordid and fertile landscape of intergenerational intimacy. It’s a desire that continues to mold who we can become. We’ve reached epiphanies similar to the ones that sticky these pages. There are childhood fantasies; and then, there is “Jack who gives the best blowjobs,” and “Jim who has the best cum in Simi Valley.” Fantasies realized and revised.

I should have learned from Michel Foucault’s Friendship as a Way of Life that these relationships do not define us. They uncover what might be possible when we embrace what he called “desire-in-uneasiness.” It’s uncomfortable to sit with the notion that my youth was desirable. Still, I remain grateful to the men of my past, for showing me what it means to be a vessel for pleasure. The truth is, my experience—and Seande’s experience—is a common one. Sometimes, it’s the only path to community, resources, and recognition in circumstances that otherwise provide no roadmap to a happy life. Trust is inevitably misplaced; comfort is necessarily displaced. All for a glimpse of what it feels like to be close to another without judgment. I could imagine what kind of life might be waiting on the other side of adolescence. At that age, sex is an existential matter. Through trial and error and their necessary risks, Seande learned instinctually that, when someone tells you to cum, you are well within your right to ask, Why? It’s a question that perforates these daily entries, spanning one formative year in the life of a star.

To some, DeLear’s diary’s publication may feel dangerous in its insistence of her adolescent agency. Her voice makes room for necessary nuance in an ongoing conversation about consent in queer community. This tension is what makes the book important. Queer desire has always been marked as dangerous. The regulatory forces of morality, law, and public health continue to dictate who and how we love. For young Black queerdos, there is often nowhere to hide from the public and private policing that attempts to keep us from what we want. Whether it was a cop busting her for cruising, or porn magazines confiscated by Mom and Dad, Seande let little to nothing stand in the way of the inertia of her desire: a by-any-means-necessary drive toward a want that burned in its refusal to be denied. I imagine what I might have gleaned from these diaries in 2016. New tactics of temptation reveal themselves—unfamiliar perils, too.

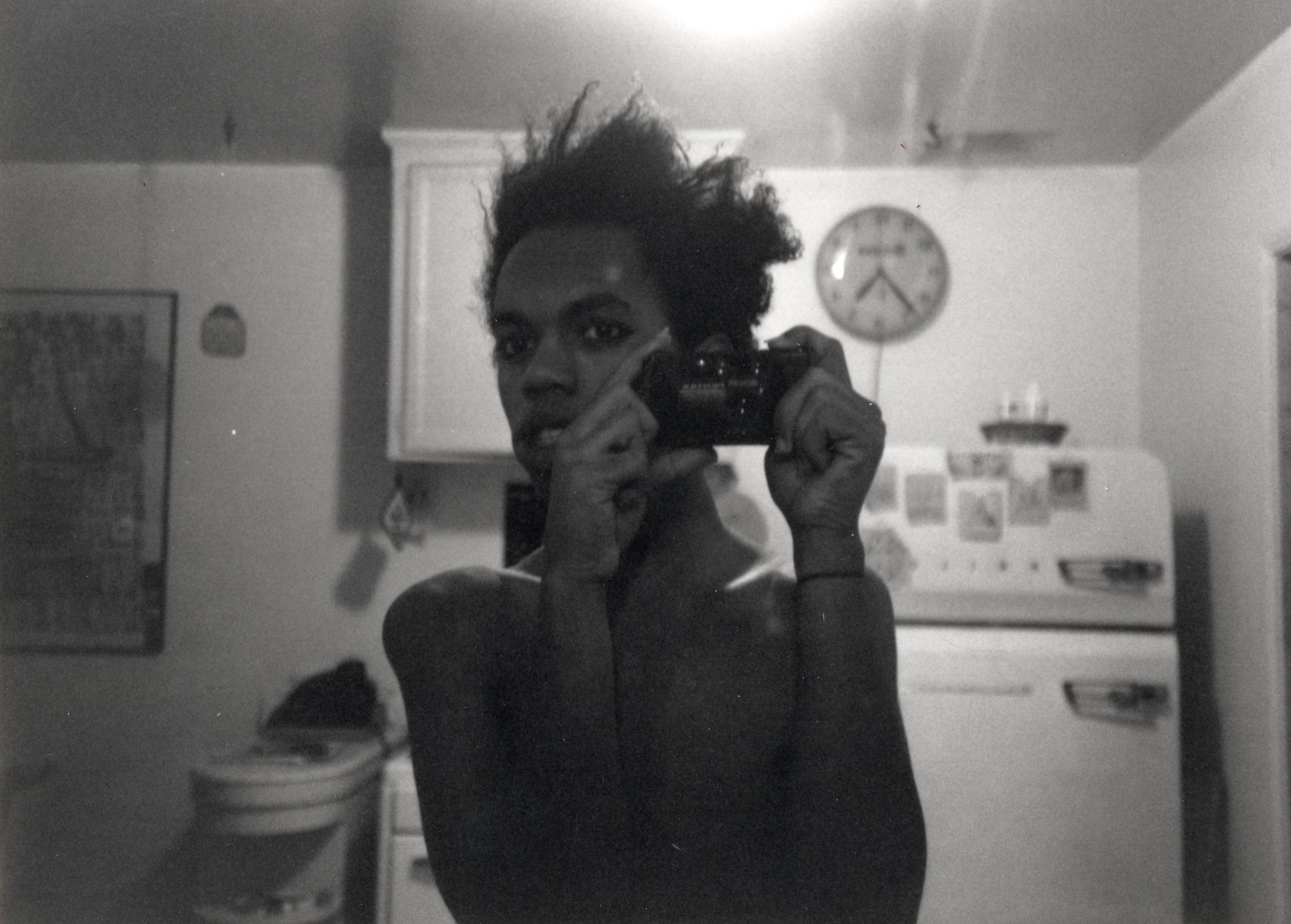

Queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming bodies continue to shift in relation to one another, but some things remain true: We will always want to fuck. We always have. I always have, at least. Seande’s words reflect the realities of generations of queer kids, whether they knew her or not. Reading her diary in the wake of her passing—bearing witness to this parallel Southern California childhood—felt like connecting to an ancestor. A vicarious, astral convergence of past and future lives. A face that is not mine, yet not unlike mine, looks back at me.

Growing up in quasi-suburban Los Angeles in the 2010s, I may have been too comforted by the apps to brave the public toilets. But I identify with the high-risk, high-reward impulses of youth that drive us to connections much of society would rather remain unrealized. (I, too, stole a parent’s car to meet tricks. The only difference was, I didn’t get caught.) Seande gropes her longing shamelessly, like the bulging denim she encountered at the Simi Swap Meet. She maps the size of puny participation trophies and big dicks alike. She sums up this distinct phase of life perfectly: “I want to suck some cock so bad. Sorry, I thought my mom was coming.” The diary’s publication makes clear that we do nothing in the dark, and we do nothing alone.

DeLear’s words reveal an intimately honest—albeit accidental—archive of an icon in the making. This sublime portrait sits petulantly in the growing canon of the Black queer bildungsroman. In the ripples that emanate from Samuel R. Delany’s seminal autobiography The Motion of Light in Water, there are glimmers of recognition, sparkling in the tile of the bowling alley tea room, and seat belts left unfastened in the cars of friendly strangers. These moments of clarity (post-nut or otherwise) are the progeny of Delany’s “heart-thudding astonishment,” witnessing gay sex en masse at the St. Mark’s Baths—a feeling “very close to fear.”

Proximity to this fear grows more distant with each iteration of this story of becoming. Delany and DeLear encounter distinct pleasure in contexts that resemble peril, capturing the sensory symptoms of self-actualization and making them known as such. Their accounts don’t render our personal experiences any more certain; caution still proves necessary in navigating the slippery surfaces of unfamiliar bodies. However, the lessons gleaned in these flashpoints speak to the potential ecstasies awaiting those who cross the threshold. These memories are a reminder that these infrastructures of desire may still hold some value. We have a generation or two of queer wisdom to guide us now, and their knowledge may reside just below the skin.

The rest of Sean DeLear’s fabulous adult life remains an epilogue to these diaries. A more hopeful story of queer becoming than Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight. Instead of succumbing to the proscriptive conditions set before us, queer folks maintain the power to defy them altogether. Seande’s transcendence of gender, genre, and culture prove that such a reality is within reach. In brash, daring vignettes of desire—depicted against the daily mundanities of teenagehood—her youth is a beacon of clarity. Seande’s memory continues to be circumscribed only by the limits of her own interiority. Her witnesses, here, are kindred companions.