Grounded by a shared affection for contemporary folklore, the two artists meet to discuss trompe l’oeil, gender-hacking, and queer visibility

Pippa Garner is an angel of American industry. Originally trained in automotive design, her creative career found its footing in the 25th Infantry, where she learned to draw while serving as a US Army Combat Artist during the Vietnam War. Garner’s work continues to romance the commercial and the conceptual, fragmenting across nontraditional mediums—custom cars, garments, mail-orders catalogs, and flesh—echoing the sunny absurdism of Los Angeles, where her practice is based. Garner’s first New York solo show in, $ELL YOUR $ELF, turns expressions of consumerist exhaustion into something wonderful, embracing the perversion and pleasure of mass production. For Garner, the border between body and appliance is slippery; she describes gender-hacking as an extension of her work, using her skin as a raw material. Clad in a tattooed bra and panties, the artist relishes in self-transformation, against the sheen of pristine packaging.

Like Garner, artist Gray Wielebinski’s affection for modern folklore allows for deft criticism of Americana, while working within its laws. He’s a man of myth—drawn to the precarious tenants of nationhood, pulled from his Texan upbringing. Upon completing an MFA at Slade School of Fine Art in London—where he still resides—Wielebinski found home in the transitory space between concrete labels of gender. His work often grapples with themes of desire, power, and surveillance, taking form across sculpture, drawing, video, performance, installation, and sound. Wielebinski’s most recent piece, Exhibition, is both alluring and arresting—an homage to the public restroom as an innocuous monument of queer and trans existence. With the roaring brilliance of a home run, the artist recasts reality into a collage of its fragments.

As the dawn of an expansive queer consciousness eclipses the pressures of professional cohesion, Garner and Wielebinski piece together new dimensions of personhood to find out what makes a body more than the sum of its parts. Here, the two artists meet to discuss trompe l’oeil, gender-hacking, and queer visibility.

Pippa Garner’s $ELL YOUR $ELF is on view at Art Omi through October 29.

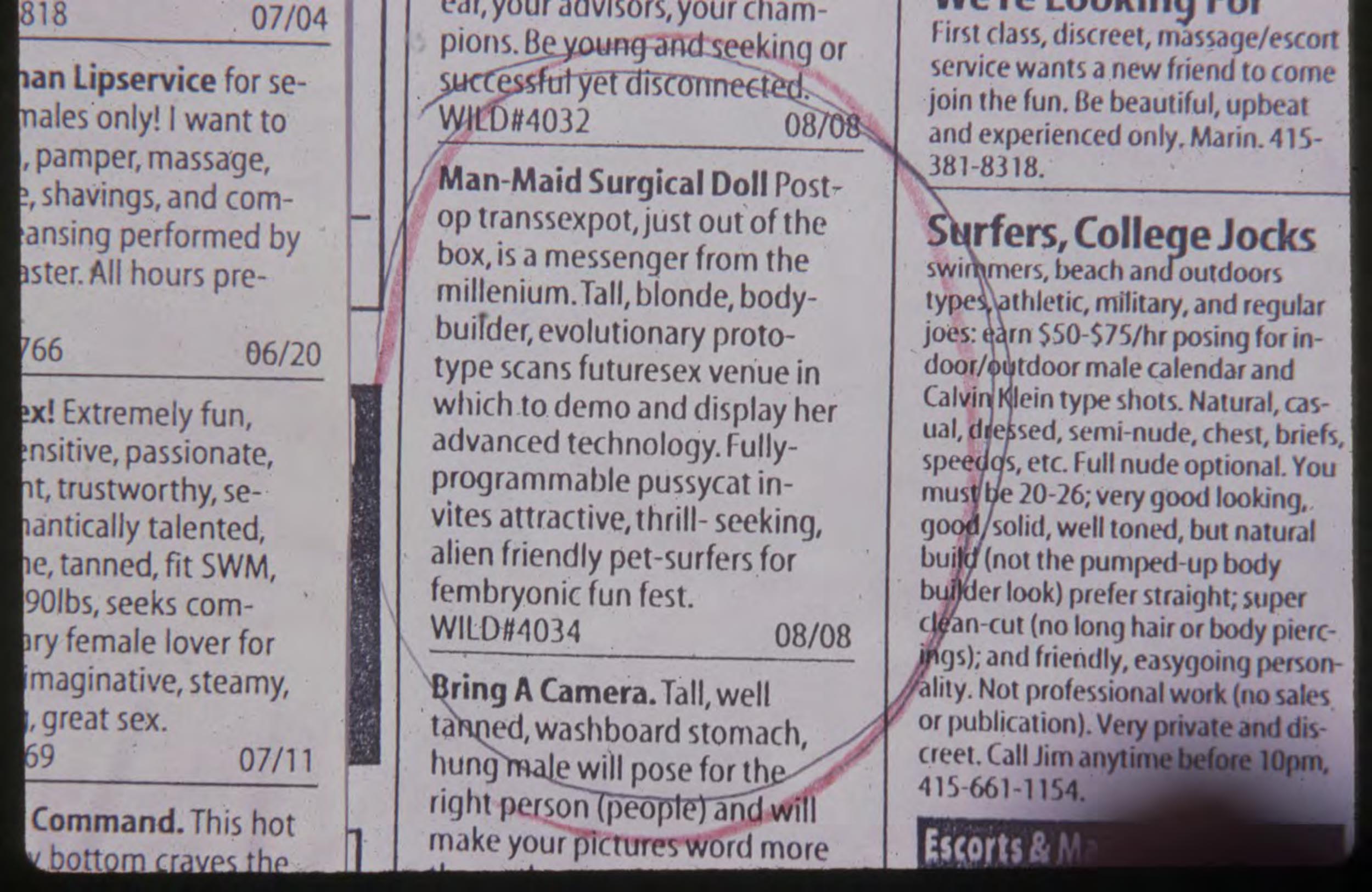

Gray Wielebinski: The first time I saw your work was via your t-shirts. They feel timeless, [which] comes from the balance of your humor; it’s acerbic, and doesn’t feel like you’re punching down. I wanted to know more about your relationship to comedy—in your work and in your life, as well.

Pippa Garner: To some extent, it may [relate to] the sequence of periods that have gone on during my life. I was born in ’42; that was the start of WWII. As a small child, I remember some of the deprivation. There was this desire to pretend that it didn’t happen. I found the whole thing slightly absurd, I guess—amusing. I became particularly fascinated with automobiles, as many people my age did at that time.

But the human part of it, I can’t fully explain. It’s partly an affection for all these things; I kind of loved them, you know—the cars and the counters and the waffle irons. It was these wonderful things that man made out of the materials he refined from the earth. The other thing about it, too, was the huge amount of obsolescence. Everybody would be fascinated, thinking [a product] was wonderful. Almost immediately, something better would come out and the previous thing would be suddenly valueless, ending up in thrift shops and yard sales. As far as how the humor started, I’m just not sure. It’s the way I look at things.

Gray: I like what you’re saying about returning to, or never leaving, the things that imprint on you in childhood. I’m also an artist, and a lot [of what] I’m coming to now are the things I was really obsessed with as a kid.

I grew up in Dallas, lived in LA, and I live in London now. But I feel like car culture always represented freedom. At the same time, it can be isolating. It relates to transness, but also to the human experience of how you present yourself to the outside, and have this internal life.

Also, [your use of] trompe-l’œil—similar to your humor—feels like a punchline. But actually, it’s an invitation to get closer to people , and to have this relationship with these seemingly different elements of your work.

Pippa: It’s a product to me—the body—just like any other thing. I look at the mirror and I think, I was designed to be a genetic male, hunky, middle-class. When I was born, it became my identity. As an adult, I knew I was able to thoroughly integrate the inside and outside, like two different beings.

Gray: I’m intrigued by your relationship to transitioning via hormones, coming from this established tradition of framing the transition as an artwork, or as gender-hacking.

I feel like that deviates somewhat from what’s now become—at least in my generation—more of a mainstream discourse around transness. Especially now, with professionalism and social media, it feels like [there’s] a pressure to be a finished product; to be cohesive and to have clean narratives, whether they’re tragic ones, about being in the wrong body, or if they’re more earnest.

Pippa: It was in the mid-’80s—I ran out of interest in consumer products. The work was starting to repeat itself. I was always fascinated with the human body. In order to draw the figure properly, you can’t just sit down and draw it like you would something else. A car, for example—you only have to know what the outside looks like. You don’t have to know anything about the cooling system or the transmission. When you try to draw the human body, it’s the opposite. If you want to make it really look real, you have to have that inside—almost like sculpting materials on a flat surface. This was probably what caused me to evolve from working with material stuff, like appliances. I started looking at myself in the mirror: This appliance that I have, what can I do with it? How can I have fun with it?

“I started looking at myself in the mirror: This appliance that I have, what can I do with it? How can I have fun with it?”

I felt like [testosterone] was affecting, for one thing, my relationship with women. During the ’60s and ’70s, everyone was having sex with everybody. I got to a point where I thought, Well, I’m blocking half the human race. I look at them and I’m thinking of their body and how attractive they are sexually—missing the point, really. I [didn’t] want to do that anymore, and I thought, What if I just knocked that down a little bit by taking some estrogen? What would happen? That was the first experiment I did, way back in the mid-’80s, so I had to get it illegally. I tried to get it from the doctor and they wouldn’t prescribe it. It was a liability, I guess, to give it to somebody without definite medical needs.

Gray: They still do that, even now.

Pippa: I went out in the street—Hollywood Boulevard. There was no real term for ‘transgender.’ They were ‘crossdressers.’ I found one and said, ‘Excuse me, could I get you to tell me something about hormones?’ She sat down with me at the bus station, I gave her some money, and that was how I did it. In about three weeks, I noticed this wonderful effect: It softened the testosterone. People kept saying, ‘Hey, all of a sudden, you’re much nicer.’ I never told anybody.

Gray: You didn’t?

Pippa: No, that was my little secret. I wasn’t doing anything feminine—I just wanted to see what it felt like.

I liked it so much, it opened the doors to other things. I thought, Let’s push it to the next level. That’s when I decided I’d get breast implants. Because, why not? That really freaked people out. I didn’t care. I thought, This is good, it’s what I want—a reaction that’s pushing me in a new direction.

Gray: It’s interesting that, at first, [this was] your personal secret. Do you remember what compelled you to want to feel more seen?

Pippa: That was my ego, I guess. I was trying to do something that I thought was valuable—people should have to respond to something different.

They had been, during that time, refining a process called vaginoplasty. I said, Well, why not? I’ve lived almost 50 years as a genetic male, and am getting kind of sick of it. I wanted to constantly push the edge of things. So I did. I had to go through a year of psychotherapy; there were two or three surgeons in the world that would do the vaginoplasty, and they required that you be signed off by a psychotherapist and endocrinologist. I had to know I was in the wrong body. You couldn’t just want to do it.

Gray: Did you have to say that narrative, though? That you were in the wrong body—even if you didn’t feel that way?

Pippa: Yes, I played that up. I had figured out all the right answers for what they wanted to hear, and then I did some asking around about surgeons and found the best one. I had the surgery. I came back a week later with a vagina. It was all secret.

Gray: Even at this point?

Pippa: Some people would see me as female, and some as male; I never got over that. I still get weird looks once in a while, and I’ve [faced] some real discrimination. But I never regretted it for a second. It was the right thing to do for the rest of my life.

Gray: I noticed you still use what is now called a ‘deadname’. But for you, your previous identity is a part of your life and who you are. It’s how I feel with my transition, too—and sometimes I can be a little shy, or nervous about how I felt before. At the same time, I feel like it’s this privilege that I’ve gotten to live multiple lives. We all only have one life, but transness is one of the ways we can think more openly about having more experiences, and connecting to people in different ways.

You changed something that let you connect more sincerely to yourself, but also to the world around you, which is a really cool way to think about transition or gender-hacking, or also just self-actualizing—making changes and wanting the most from your life.

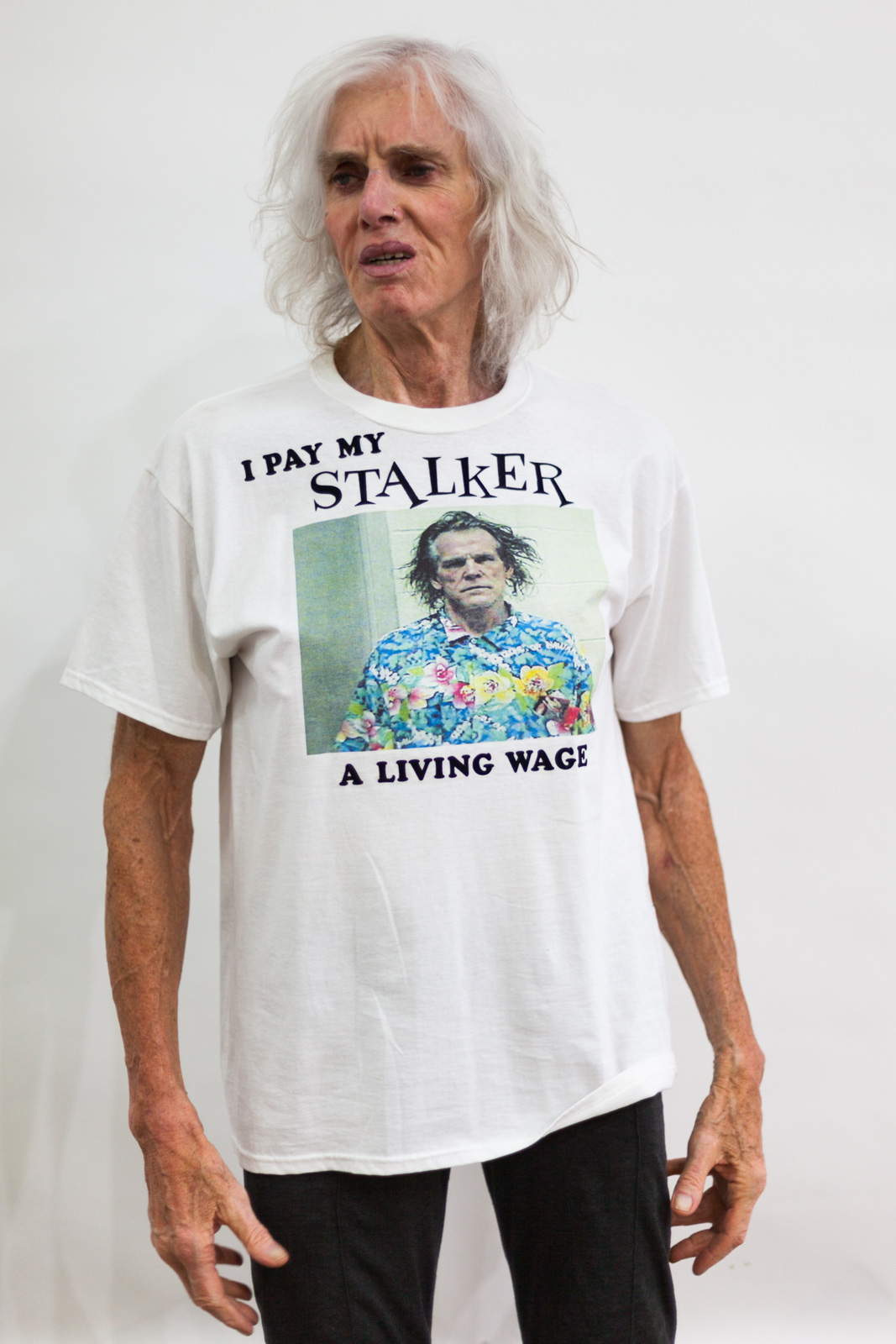

Pippa: We only have one life. I have to do something absurd for my birthday every year. Last time, I had a t-shirt that said, ‘I’m 80, but my tits are 34.’ I could send you a picture, if you’d like.

Gray: I would love that.

Pippa: I do another for April Fools’ Day, too. I don’t celebrate my birthday, or anything else. I think that’s the only holiday that, for me, has any deep significance.

Gray: What’s the deep significance for you?

Pippa: Everyone thinks it’s for children. But I have to make some display of it. It has a very deep history: Ancient cultures would have a day where everything would be different. All the aristocracy and the peasants would swap places. It goes way back.

You’re living in London?

Gray: Yes, I am.

Pippa: I spent two years there, in the ’70s. It’s a great place.

Gray: It’s funny, what you were saying about consumerism. I have a joke. I don’t know how funny it is. I’ve been living in London for six years. And even through my transition, one way in which I identify is as being ‘cis-American’—because there’s not really much ambiguity where I’m from. To some degree, consumerism and American ideologies are just kind of ingrained in me, for better or for worse. I don’t know if that hits at all for you. But I feel like that’s one part of my identity that’s very staunchly cis.

Pippa: Identity, gender identity—that plays out in commercial things. It still exists. Magazines still have women that are totally made-up, and super masculine men. I guess I find that interesting, that it becomes a good selling point—male or female. It’s artificial because it’s commercial; it makes money.

Gray: Categorizing can be a way of being seen. But consumerism is feeding part of it, too—kind of like the chicken or the egg. It can be good, but it also means that there’s more of a market that can be sold to. Your work is very prescient about the lifecycle continuing and evolving. There’s a really beautiful sentiment to that. Then there’s the kind of nefarious—or, at least, capitalist—tale of, How can we make money from this?

Pippa: Toward the end of my life, I don’t like to think about that very much. Most of the work I do is—immature isn’t exactly the term—but it hasn’t evolved that much to me. I still have the same attitude toward my work as I did many years ago. I’ve been producing things that attract me to things I want to play with. And so, again, I’m thinking: To the extent that your heart quits beating and your new body dies, is there a way of keeping it fresh somehow? Dying with a smile? If I could keep my sex life alive, then my consciousness would carry through somehow. I want to die alive. That’s maybe a way of transferring life, or taking some of it with me.