As news of the missing sub unfolded in real time, millions grappled with the choice between empathy, and reveling in the the poetic justice of a modern-day parable

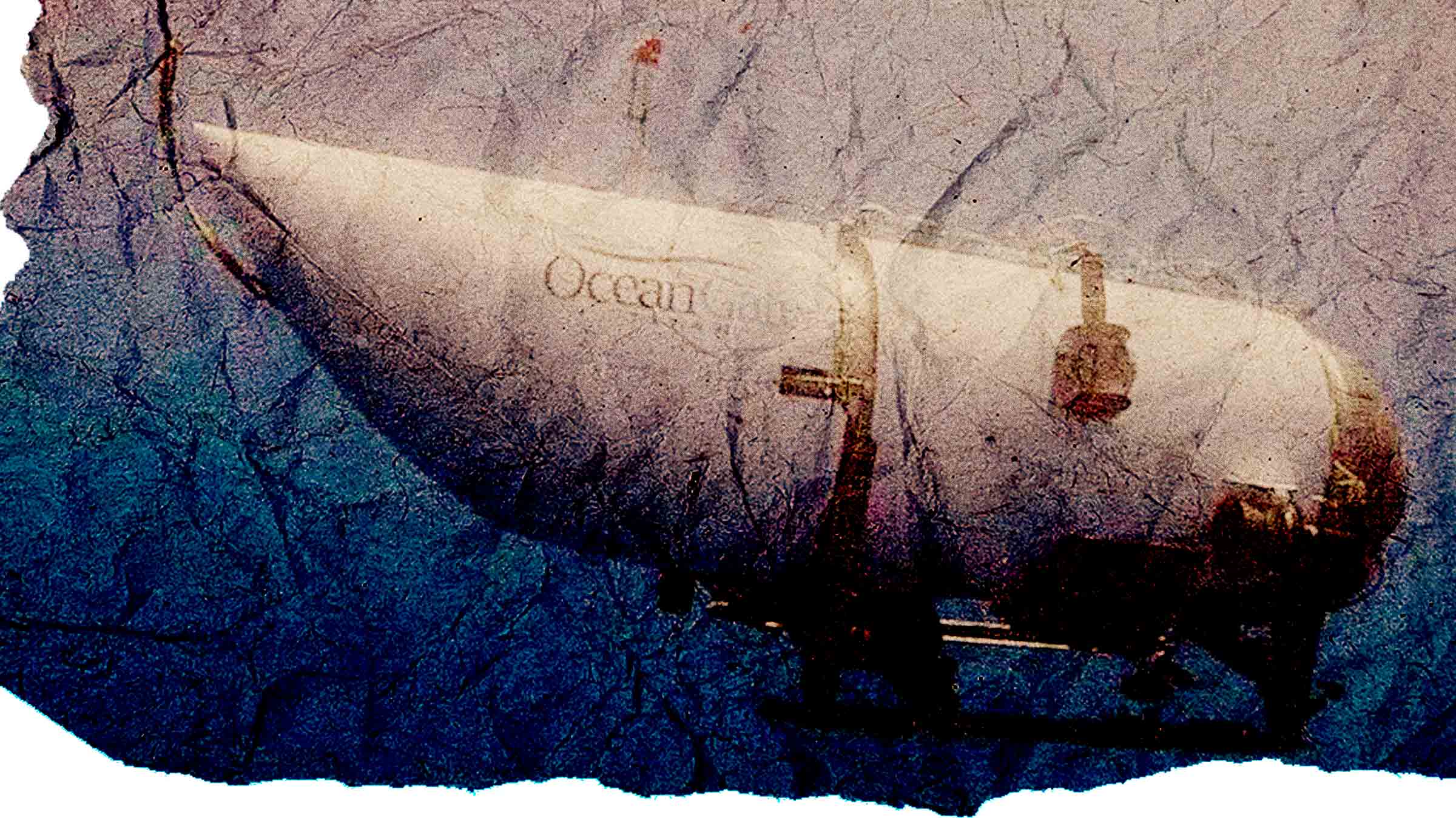

When I first heard about the submersible, I had just embarked on a 48-hour getaway—one that happened to coincide with the search for the missing vessel, which had ceased contact only two hours after starting its dive to the Titanic ruins: a $250,000 excursion offered by OceanGate Expeditions, a deep-sea tourism business geared toward ultra-wealthy adventure-seekers. At the time, the billionaires onboard had an estimated 40 hours of emergency oxygen left—and with rescue missions racing against the clock, the story was rapidly saturating news sites and social media feeds. Which is why—despite my stated intention to disengage from the discourse—I found myself scrolling through Twitter in the passenger seat of a budget rental car, unable to look away.

Over the course of the drive upstate, more details began to emerge—each seemingly precision-engineered to induce a sense of collective schadenfreude. Though marketed as a once-in-a-lifetime luxury experience, the submersible—dubbed the Titan—had been designed using several low-cost materials, like carbon fiber and the $25 video game controller with which it was steered. It seemed that OceanGate’s CEO—a wealthy entrepreneur named Stockton Rush, who was among those onboard when the sub went missing—had lived up to his name, not only cutting corners on the Titan’s design, but also eschewing the rigorous testing usually required for passenger submersibles. When industry experts raised alarm bells about potential safety issues, Rush dismissed their concerns. “I’m tired of industry players who try to use the safety argument to stop innovation,” he stated in 2018. “We have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often.”

Rush was able to dodge regulations by loading the Titan onto a Canadian ship, and then dropped into the North Atlantic Ocean—avoiding the rules that apply to vessels operating in American waters. Eager to disrupt the field of ocean exploration, he began offering commercial tours, despite warnings from the company’s own executives—one of whom was fired after reporting that the Titan’s system couldn’t detect flaws in the hull until “milliseconds” before a fatal disaster. The same year, the Marine Technology Society sent Rush a letter expressing “unanimous concern” about his approach with the Titan—which was designed by OceanGate and made of carbon fiber for Boeing, which he purchased at a steep discount because it was past its expiration date for use on airplanes. In 2017, Rush admitted to breaking some rules with his choice of material (most submersibles are made purely out of steel or titanium), but he did so proudly, quoting General MacArthur: “You’re remembered for the rules you break.”

Even Rush’s friends, like the submersible expert Karl Stanley—who heard the sound of the craft’s hull breaking down during a deep-sea dive—urged Rush to pursue further testing, warning him against “succumbing to pressures of [his] own creation.” So did fellow deep-sea exploration expert Rob McCallum, stating in a 2018 email to Rush that, “In your race to the Titanic you are mirroring that famous cry: ‘She is unsinkable.’”

“The specific and almost unbelievable details of the case point back to the impact of capitalism on our collective condition—swinging like a cultural weathervane from Rush’s ruthless cost-cutting… to the astronomical price the ultra-wealthy are willing to pay to experience luxury deep-sea tourism.”

It seems like poetic justice that—over a hundred years after the Titanic sank, with his wife’s relatives onboard—Rush joined its 1,500 casualties, killed by a catastrophic implosion of his own creation. But no one knew that yet—and in the meantime, the subject of the missing sub was rapidly becoming both a media spectacle and a moral battleground. The story had taken over the home pages of news sites and social feeds, where #Submersible had accrued millions of views: onlookers gawking at the wreckage of the present, much as the passengers on the Titan had sought to gaze at the ruins of the past. There’s an undeniable irony to the situation: a missing submersible boarded by billionaires, who paid $250,000 apiece for a glimpse at a sunken ship—which had, in turn, been full of rich people who also met their demise after ignoring suggested safety measures. It seemed like a modern morality tale: OceanGate as Icarus, imploded into a million pieces after diving too close to the ocean floor.

Soon, my Twitter feed was full of people making jokes at the expense of the missing billionaires, while others pushed back at the lack of empathy shown for the endangered passengers. But can you really blame them? In recent years, satirical depictions of the ultra-wealthy, entrapped on private islands and shipwrecks, have suffused the public consciousness, becoming so popular as to birth their own reliable blockbuster formula: one in which our collective discontent provides Hollywood execs with a chance to cash in on the desire to watch rich people squirm. So when it happens in real life, it’s hard to view the situation as much more than a headline—or, failing that, a punchline.

Checking my phone between nature hikes and home-cooked meals, I found myself playing the voyeur—passing along news of the situation to my incredibly tolerant boyfriend, or attempting, under the influence of mushrooms, to cultivate a greater sense of empathy for those onboard the submersible. But something about the nature of the event—this creeping sense of satire-turned-reality—made it difficult to wrap my head around. Much of the news is like this these days: horrors unimaginable, delivered in little pings to the same devices we use to send nudes and Venmo payments. To enable push notifications is to cultivate a form of numbness, deadening oneself to the news of unspeakable violence—children laboring in sweatshops, the catastrophic effects of global warming—that appears alongside sale announcements from SSENSE.

The experience of the missing passengers had become my own personal hyperobject—a term the philosopher Timothy Morton coined to describe phenomena humans struggle to wrap their minds around. Most hyperobjects are vast, looming in the collective imagination with societal implications too great to comprehend: things like global warming, capitalism, oil spills, COVID-19 deaths, and all the plastic ever manufactured. Unable to hold the consequences in our minds, we can only glimpse the signs of such things, because to feel their human cost threatens our reality to such an extent that one is left reeling—or else, doomscrolling.

“Satirical depictions of the ultra-wealthy, entrapped on private islands and shipwrecks have suffused the public consciousness, becoming so popular as to birth their own reliable blockbuster formula.”

Maybe that’s why we’re all making jokes: The specific and almost unbelievable details of the case point back to the impact of capitalism on our collective condition—swinging like a cultural weathervane from Rush’s ruthless cost-cutting and abuse of the move-fast-and break-things rhetoric popular amongst technological innovators, to the astronomical price the ultra-wealthy are willing to pay to experience luxury deep-sea tourism, and finally, to the “callous” response of those exploited by the system, who then dehumanize their oppressors in return.

Over the course of my trip, I found myself in the rare position of witnessing this at a distance—within the relative luxury of a house upstate, a place I had absconded to in an effort to escape from those very horrors, to touch grass, to have sex with my boyfriend. I’m a working-class writer living in New York, more politically allied with those making fun of the missing billionaires than those defending their humanity—yet discounting their suffering in pursuit of personal enjoyment made me wonder if this was how the wealthy feel all the time, witnessing the impact of the systems they benefited from, and looking the other way. After all, wasn’t it a waste not to enjoy the view?

Conflicted, I turned my phone off, took some mushrooms, and tried not to think about the submarine, or about the countless other headlines that similarly feel like satire-turned-reality: “Microsoft lays off ethics team despite doubling down on AI offerings,” “Artist sells invisible sculpture for $18,000,” “ChaosGPT plans humanity’s demise.” But as people enlist hyper-powerful AI models to write jokes about the missing sub, I couldn’t help but wonder if the Sex in the City memes were a defense mechanism against the horrors of the present: a way to salvage, from the wreckage, a moment of collective bonding about our shared predicament.

The public’s attention has since shifted to Rush, with people condemning the brazenness with which he attempted to apply Silicon Valley principles to an industry ruled by the laws of nature. Old email exchanges are being dredged up, invoking comparisons to Elizabeth Holmes and other would-be inventors who crashed and burned in ruthless pursuit of “innovation.” Such stories function as a new cultural mythology that—rather than championing the “bootstrapping” rhetoric of American entrepreneurship—bears witness to how those who cut corners in pursuit of capital often wind up paying the price.

On the last day of my trip, I checked my phone, and learned that the passengers were dead. I didn’t feel anything, but relayed the update to my boyfriend, who responded simply, “Bummer,” handing me a cup of coffee. I looked at Twitter, where the jokes continued to roll in. My phone pinged. I checked my email. Vacation was over. Life goes on.