Ahead of the release of ‘Myuthafoo,’ the composer joins Document to detail the dynamic process of her craft, and unpack its origins

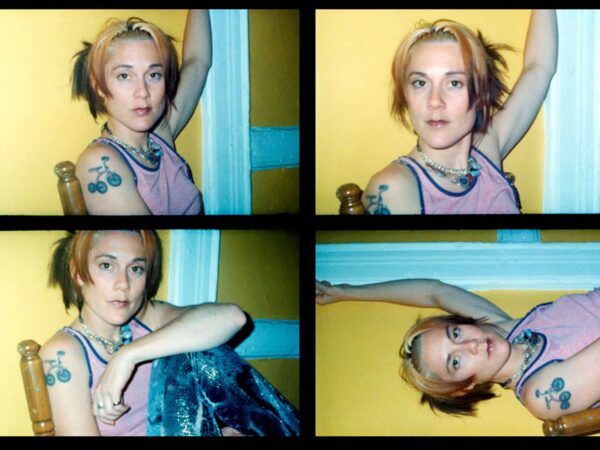

A modular synthesizer, Caterina Barbieri explains, is like a wild horse. And she has no interest in trying to tame it. Its unpredictability, in fact, is exactly what animates her practice. It demands improvisation—something the Italian artist sees as integral to her music-making process. Each piece she composes is treated as a living entity, allowed and encouraged to react to the world around it.

Live performance on this volatile instrument creates ripe grounds for facilitating a track’s evolutions. To cement a song into an unchangeable album is then almost antithetical to Barbieri’s artistic ethos. But the pause of the pandemic brought new perspective to her relationship with recorded music. Now, she sees it like a picture, a memory. There is no “finished” product. A record is merely documentation of a particular stage of a piece’s life.

The evanescent nature of Barbieri’s practice is perhaps best exemplified by Ecstatic Computation and Myuthafoo, which she refers to as sister records. The basis of each was written during a heavy touring cycle (and, consequently, their writing and rewriting)—but the former was released in 2019, and the latter is only now, four years later. Their foundations exist in the same time and space, but they are invariably different. Both contain music that has continued to depart from its original form, captured or “photographed” at different points in their lifespans.

Central, too, to Barbieri’s craft—though not unrelated to the import of live improvisation—is music’s capacity to alter the mind. Her work is an exercise in inducing trance-like states, in herself and in her audience. Employing sequencing techniques and pattern-based operations, she taps into the transcendental potential of sound. In Barbieri’s hands, the past and the present fold into each other, and technology and biology are intertwined.

Ahead of Myuthafoo’s June 16 release, the composer joins Document to detail the dynamic process of her craft, and unpack its origins.

Megan Hullander: Because the live element of your work is so integral to your creative process, is there any sense of physical space that you associate it with? Or does it feel transitory, since you were writing and rewriting in different spaces and cities?

Caterina Barbieri: Usually, I develop the pieces from performance to performance, and the form gradually crystallizes into an actual song or piece. For me, it’s very important to kind of integrate the feedback of the process, as well. I think my music is influenced by the type of venues I got to play at the beginning of my career, especially big industrial spaces. One of my favorite venues in the world is Kraftwerk in Berlin. It was a power plant factory, but it really looks like an industrial church—incredible, high ceilings; big, massive reverb. A lot of people that play there tend to work with drum music, or very ambient, textural dark tones. But for me, I was really interested in playing with the reverb of the space and in hearing isolated gestures, and the decay of sound. So, I started working with these patterns, with very isolated melodic gestures. And that really influenced my style, because I started working with intricate melodic patterns. I was really inspired by how the space was reacting to this, because it was adding melodic information, creating reverberations and delays and echoes. I think this is an essential element of music history—like, if you think of how churches in the past influenced the development of polyphonic music, just because people were singing and hearing their echo, the response of the space. Physical space really affects music.

Megan: What is your relationship like with some of your older releases, considering that the pieces themselves have evolved beyond their recorded versions since?

Caterina: Listening to a record is really like looking at a photograph. It belongs to the past. And so it’s a bit like looking at a ghost. It can be very melancholic. But in performances, I keep that connection alive. It’s a way to bring back life to music; I update and refresh those feelings, [so that they’re] connected to the present.

It was a bit trickier with my last record, because I composed it during the pandemic, so I didn’t really have the chance to play it live for a long time. I expanded my sonic palate, because I composed in the studio for the first time. That’s the record that’s more crystallized, more dead. It’s a bit more painful to listen to [for] that reason.

Megan: How, then, does cementing music into a record serve you?

Caterina: It’s like you have layered memory of all the live performances, and the music becomes this living organism. It’s super painful to accept that this complexity gets reduced into a dead format on a record, and that it’s only one of the many possible manifestations of all these memories.

I think I learned a lot from my previous experiences of recording, and I’m a bit more flexible. I’ve learned to embrace this kind of impermanence, where the music is one thing, and the studio album is [another]. And I think it’s really important to give that to the audience—especially during the pandemic, because records were the only possible outlets to experience music. Putting out a record is a strong statement—it’s like a manifesto of your style. But live performance is essential, because that is the essence of music: sharing it with other people in a collective format.

“Listening to a record is really like looking at a photograph. It belongs to the past.”

Megan: Are there any parts of your practice that feel collaborative, beyond that relationship with the audience during a performance?

Caterina: I think the label is really a response to this urge that I started feeling—this need for a more collective format. It all started during the pandemic, actually, because I felt so isolated. I mean, everybody felt isolated. It was traumatic, not being able to share music, but it felt very dystopian to keep making and releasing it. I think the label was a way to heal this wound. The way I launched the label was by arranging these shows, where I was inviting friends and a constellation of artists that I really respect to join me on stage. It was healing, just being able to share this common language with people who work on a similar wavelength.

The day I launched my label light-years was the day that Peter Rehberg from Editions Mego passed away. And it was such a tragic coincidence, because he had been my mentor, and I was so looking forward to sharing this new chapter of my life with him. But, in time, I saw it almost like a continuation of [his legacy], because the music scene I’m a part of has been deeply influenced by his work.

Megan: What do you think the connective thread of that scene is, beyond genre or sound?

Caterina: I think it’s a certain vision of music. It’s a very spiritual approach to sound and electronic music, very devotional—this idea that music is a transcendental form of art, something that elevates the spirit, that can really nurture and nourish it. I don’t mean it in a religious sense at all. It’s more like this common language that can bring people together and have empowering social effects.

I feel I’m part of a certain tradition that is defined by female composers. It’s a very specific way of telling a story—it’s quite visionary and mystical. I’m really inspired by female pioneers in electronic music. I think of people like Laurie Spiegel or Pauline Oliveros or Éliane Radigue, who all had a deep, spiritual approach to music and synthesizers, and really valued their own instinct. Éliane Radigue was basically meditating with an ARP synthesizer, and she was really into Tibetan and Eastern philosophy. Back in those years, nobody was even able to conceive of such an open-minded approach. All of her colleagues were super theoretical about music, and almost dismissive towards her way of talking about it. It’s a tradition I really value, the spiritual approach.

Megan: From a technical standpoint, what about electronic music do you think is suited to exploring those sorts of ideas?

Caterina: I’m very inspired by repetition and recursive elements, because they really create a hypnotic state—and, for me, music is a form of hypnosis. I’m interested in creating a very specific state of mind that is close to a trancelike state—and I’m interested in exploring the psychophysical effects of repetition, which bring you into this state where time seems to stand still. But actually, it’s constantly moving and quite dynamic. The first piece of gear that I bought was a sequencer because I knew I wanted to work with the permutation of pattern, almost as a way to reprogram the brain.

Megan: Do you think that lack of predictability inspired your urge to improvise?

Caterina: Yeah, it’s what most attracted me to it. When I was a teenager, one of the first bridges into electronic music was the computer music scene, in the early-2000s. Like, all of these guys playing laptop music. And that’s still a big inspiration for me. But it was quite controlled and produced and structured. Now, there is a super big modular resurgence, but in those years [when I first started], I felt extremely vulnerable playing the modular—there was a lot of risk, playing live. But, in time, I really embraced this vulnerability as a strength. People love that mobility in the context of a live performance, because they feel more engaged and more involved when you’re taking risks. Like, What is she going to do now? It’s very vital, that feeling that something could go wrong, because it leaves room for people’s imaginations. When a track is prepackaged, of course, you can enjoy the beauty of that production, but there’s not so much space for imagination. It’s very tied to the instrument that I play, because modular is a really wild horse. It’s a bit like life: Life is too beautiful to be tamed or to be controlled. It’s an illusion that we can somehow control our lives. I like that impermanence.