Following a two-night run of her show at Pioneer Works, Jibz Cameron joins Document to philosophize on Jack and Rose, tragedy addiction, and the nature of performance

The elevator pitch for Jibz Cameron’s multimedia performance Titanic Depression goes like this: “I am doing a thing based on Titanic, but it’s about neo-capitalism and climate change. And the Jack character is an octopus who is disguised as a hat.”

Taken out of context, the show’s details exemplify the alluring absurdity Cameron has built her reputation upon: Its iceberg is a mountain of garbage; its villain, a dim-witted dildo in a single black loafer. There’s a map of horrible men, featuring historical pillars of pleonexia: Benjamin Guggenheim, Mark Zuckerberg, and even the very worst of Cameron’s own family tree. But as a whole, the show actually makes a lot of sense—each detail weighted with symbolic meaning, bound to the straightforward narrative of a woman grappling with greed in all its forms.

That chaos-veiled meaning is best embodied by the tragicomedy’s Rose—sort of a conglomerate of James Cameron’s character and Jibz Cameron’s self, rendered via the latter Cameron’s queer vaudevillian alter ego, Dynasty Handbag. Narrated in part through manic text therapy, Titanic Depression’s Rose is more accessible than Kate Winslet’s: body-conscious and desperate for affection, and unsure of her place on the boat and in the world. She’s silly and she’s spoiled, but she’s also sympathetic. Cameron is funny—and so, she’s easily labeled as a comedian first. But it’s storytelling that drives her work: the human nuance that makes it resonant.

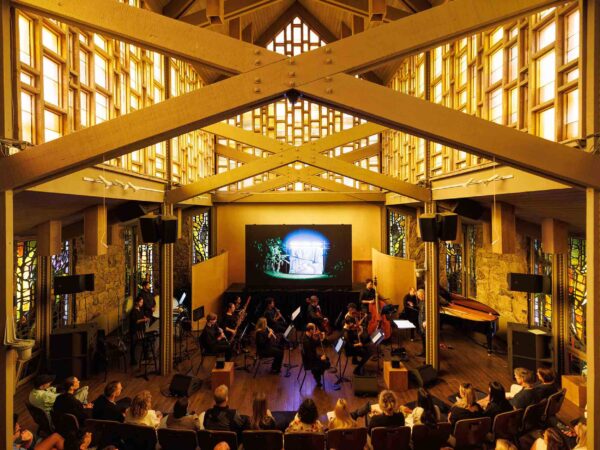

Following a two-night run of the show at Pioneer Works, Cameron joins Document to philosophize on the nature of performance and expound upon the thematic intentions of Titanic Depression.

Megan Hullander: Were you just watching Titanic on loop while you were working on this project?

Jibz Cameron: I watched—I think—all of the Titanics. There are two or three mini-series and five films. There’s one that was made in Germany in 1944, during the war. And it’s funny, because it’s basically anti-British propaganda: ‘This thing sank because they’re all fucking idiots.’

[The idea for the project] started out on a cruise ship. I was thinking about Trump, and this return to Baroque ’80s opulence—and the cruise ship was such a big part of the ’80s. At some point, it just turned into Titanic. It was not a big movie for me. But I started to think about it as like, Something’s gonna go wrong on this ship. And obviously, that sounds familiar.

Megan: Did you find any affection for the classic, in rewatching it so many times?

Jibz: No, it’s pretty repulsive. But this thing came up, which always comes up in performance: How do I center myself in the story, so that it doesn’t become just me talking about something? I started having to watch the film and really try to relate to Rose, which is, like, very humiliating and humbling. I had to take it seriously. I mean, it’s so ridiculous, the movie—just a reductive display of poverty and wealth. Every Titanic story uses an exploitative emotional narrative to propel it forward—but this one was so grotesque.

“I started having to watch the film and really try to relate to Rose, which is, like, very humiliating and humbling.”

Megan: The way that you perform has an improvisational quality, where it feels like it’s happening in real time. Is that something that you consciously write in, or do you leave space for moments like that in performance?

Jibz: Well, I know that I can wing a lot of things. Comedians always say they write on-stage. There are a lot of things that will be a concept, and I know I’ll figure the dialogue out, according to the way it’s flowing.

I somehow never, ever have enough time to rehearse. So I’m like, Last-minute blank? I’ll just figure it out. But this show required a lot of concentration; it did not have a lot of improvisation. I was focusing so hard, listening so hard, and trying to hit my cues. I didn’t really know how the show was going. I had a sense that it was going fine. I’m excited for when it gets really in my body, and I can play around [with it].

Megan: Absurdity is also something that recurs across your work. I wonder if your understanding of it has changed—as, with our increased exposure to the world, life is actually a lot more absurd these days.

Jibz: It’s very important for me to have a connection to the material and not make things that are absurd for absurdities’ sake. I just don’t really write or think that way. It’s funny—there was this thing in the New York Times saying that [my work] was surreal. And experientially, it is surreal. But my brain is not surreal. It’s pretty clear in my head, what things mean—and they all mean something. With the internet, it’s brief moments of hilarity. But it’s not a full story. That’s kind of the difference between a joke and humor. There are so many funny things that will just have you ba ha ha ha, then you forget about it. But it’s important for me to have more of a story in something. I don’t know. I don’t think of myself as absurd. I’m very insulted that you said so.

Megan: Sure. Have you found that a lot of people have experienced the show in ways you didn’t expect?

Jibz: I feel really, really pleased about one aspect: It’s very sad. There’s a lot of writing in it that’s very sad. I was really happy when people were like, ‘I was so sad.’

I saw one of my best friends yesterday, and she was really taken aback by the tenderness of the octopus. And, you know—it’s vulnerable to make things that are super sincere. I think, because I worked so, so hard on the script, I knew that the show needed to have a lot of pause in it. Because I didn’t want to make a spoof. That’s why there’s not really anything in the show about Titanic. There are some iconic scenes [that I used], but they’re selected because of the things they represent to me. Like, the drawing scene: I was thinking a lot about—I hate this word—queering the hetero-fantasy scene. Like, if it was an octopus, there would be eight drawings. And as a lesbian, queer person, the consent form situation is really [resonant with] all these poly relationships. I’m not in one, but just thinking about representation. Relationships with animals are really queer, because it’s, like, a different system of care.

Megan: How do you find that balance between humor and earnestness?

Jibz: I think it’s personal work. Like, if you haven’t really processed your bullshit, you can’t make work about it. You know: when you see a documentary, and you’re like, That person’s not really ready to make this. They’re still in the story.

I tried to really be conscious of what I’m saying, and my relationship to it—because otherwise, it’s gonna come out sideways, in a way that is insincere. If you’re past shame or guilt or real trauma, you can see the humor in yourself. Like how you can make fun of yourself once you’re through something. It’s just that thing of like, Is it too soon? I look at some of my earlier work; I made some pieces about my mom that were funny. She was really mentally ill and had a lot of suicide attempts, and eventually did die by suicide. And I made a lot of work around it that was really dark. If I were watching that now, I’d be like, This girl needs help. And now I’m like, I don’t need to do that.

“I don’t mean to say that everything has to be hard. I don’t subscribe to that. But it takes a lot of effort to remind yourself that suffering, and being addicted to a tragedy, is really bullshit.”

Megan: How do you manage the emotional labor of a project that requires that vulnerability? I imagine it’s still draining, even if you have processed a lot of it.

Jibz: I had those moments in the show. One was around how I was going to deal with my own complicity in capitalism, and the extractive settler colonial history of my family. And the whole part about my grandpa was, like, three pages long. I had to really narrow it down and be like, What’s going on here, and what am I trying to say? I had to process it so that it didn’t come out as, like, an apologist thing—being like, I’m taking responsibility, so I’m allowed to do this. You can smell that a mile away.

And I can be very, Here, take everything: my money and my time. I have a punk background of, Ownership is toxic. There was a point where I was spreading the project out too much. It became about other people. I was getting way too entangled in people’s drama around it. I had to find a way to reclaim it. And I did, but it was not easy. As an artist, if things aren’t challenging, you’re not really growing. Well, no, that’s not true. I don’t mean to say that everything has to be hard. I don’t subscribe to that. But it takes a lot of effort to remind yourself that suffering, and being addicted to a tragedy, is really bullshit.

Megan: I mean, there has to be some element of joy that keeps you invested in it. At what stage do you usually find that?

Jibz: I love writing. I mean, it’s hard, but it’s really fun. But definitely just being on-stage. And then afterward, when everyone’s like, Oh, it’s great.

Megan: Has your sense of purpose in making art changed at all?

Jibz: There was a moment where I felt like, in order to keep going, I had to reframe the outcome that I wanted. The outcome being: bringing some sort of joy, or helping someone or inspiring someone or creating community. I don’t always think that way, obviously. I’m also like, Give me a Genius Award, because my ego is still there. But if I’m really nervous about a show, I can reframe it as being like, The purpose is this. I think that helps me take it out of, It’s all for me. Because that’s a surefire way to disappoint yourself.