Decades after its heyday, the historic hotel serves as a safe haven for burlesque and sideshow artists to perform their most transgressive acts

“In drag, you put on layers to reveal your true self. And in burlesque, you take off layers to reveal your true self,” says Veronica Viper. “When you get down to it, the underlying message is the same: This is me.”

We’re sitting on a velvet couch, feet away from the makeshift stage where—days later—I’ll watch the burlesque dancer shed layers of clothing, seducing her audience with a mesmerizing ease. There’s a joint in her mouth, and an aura of joy in the room—perhaps because, unlike most of the places Viper performs, this one is full of friends: fellow performers who spend their evenings onstage at the Box or House of Yes, before slipping away to the Hotel Chelsea, where the real fun begins. There, in the photographer Tony Notarberardino’s dimly-lit living room, drag queens and burlesque dancers bare all, performance artists debut acts too risky for public venues, and sideshow performers test the limits of their endurance—not for a crowd of strangers, but for each other.

If you ask Notarberardino how his living room came to serve as a second home to New York’s queer nightlife community, his answer is simple: “One thing led to another.” The Australian photographer has always had a soft spot for misfits and outsiders; it’s why he’s spent the past 20-some years documenting not only the famous thinkers and makers that once called the Chelsea home, but also the transient hotel guests, bohemian eccentrics, sex workers, drug dealers, and drag queens that often walked its halls. Sometimes, he would station himself in the lobby till 2 or 3 a.m., wait for someone to walk through the door, and ask to take their portrait. “It didn’t matter if it was Grace Jones or Sam the garbage man,” Notarberardino says. “I photographed them all.”

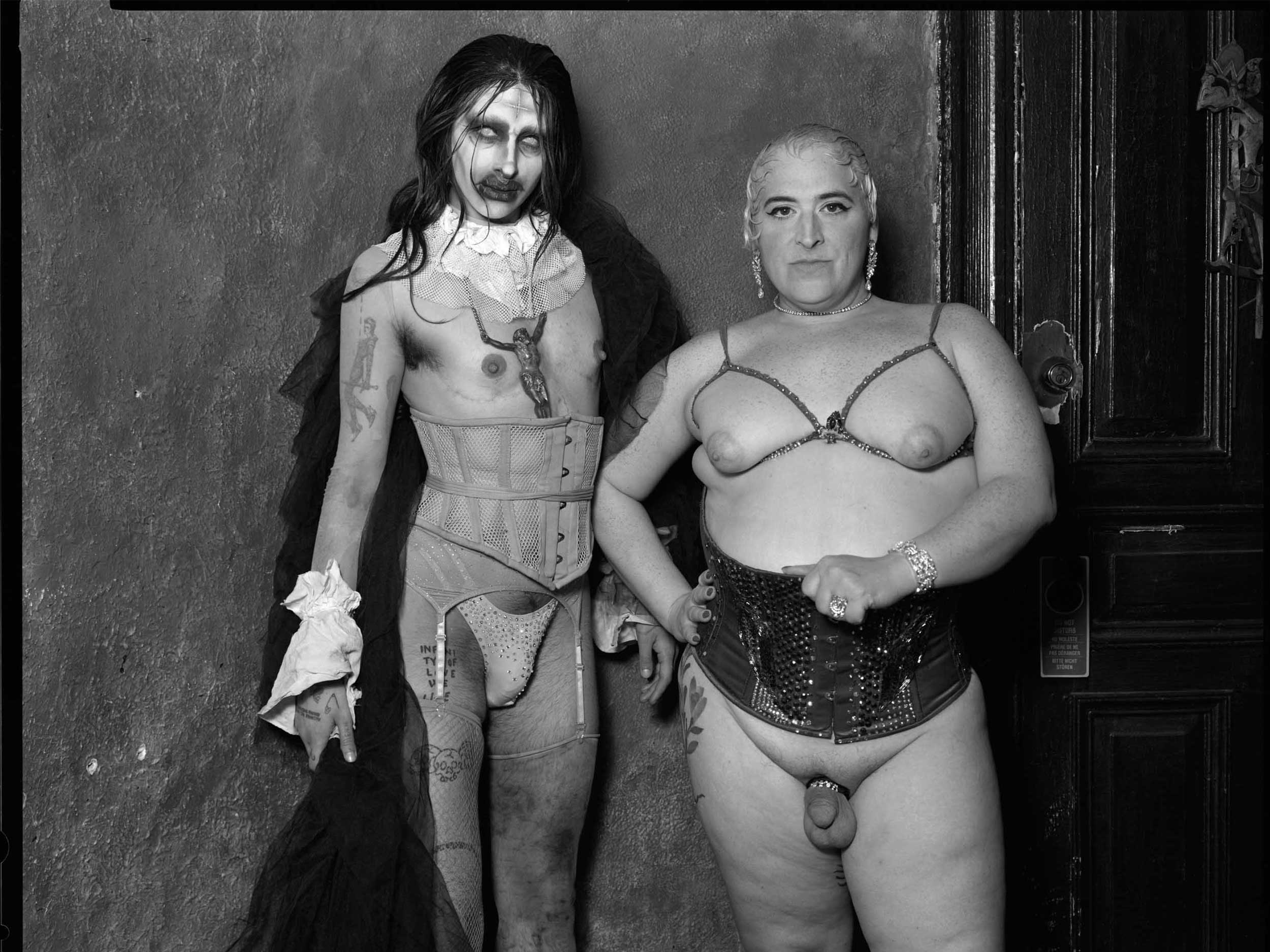

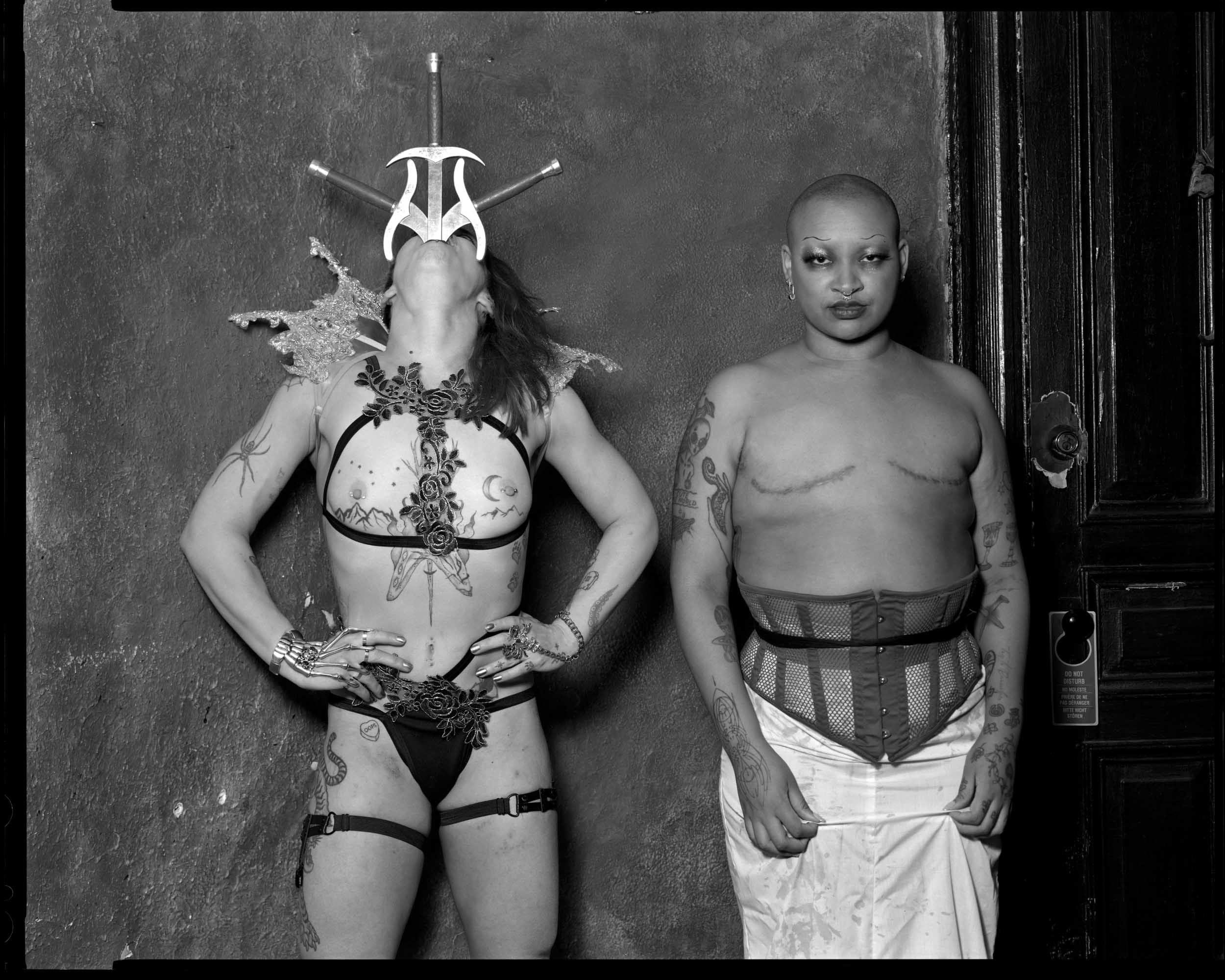

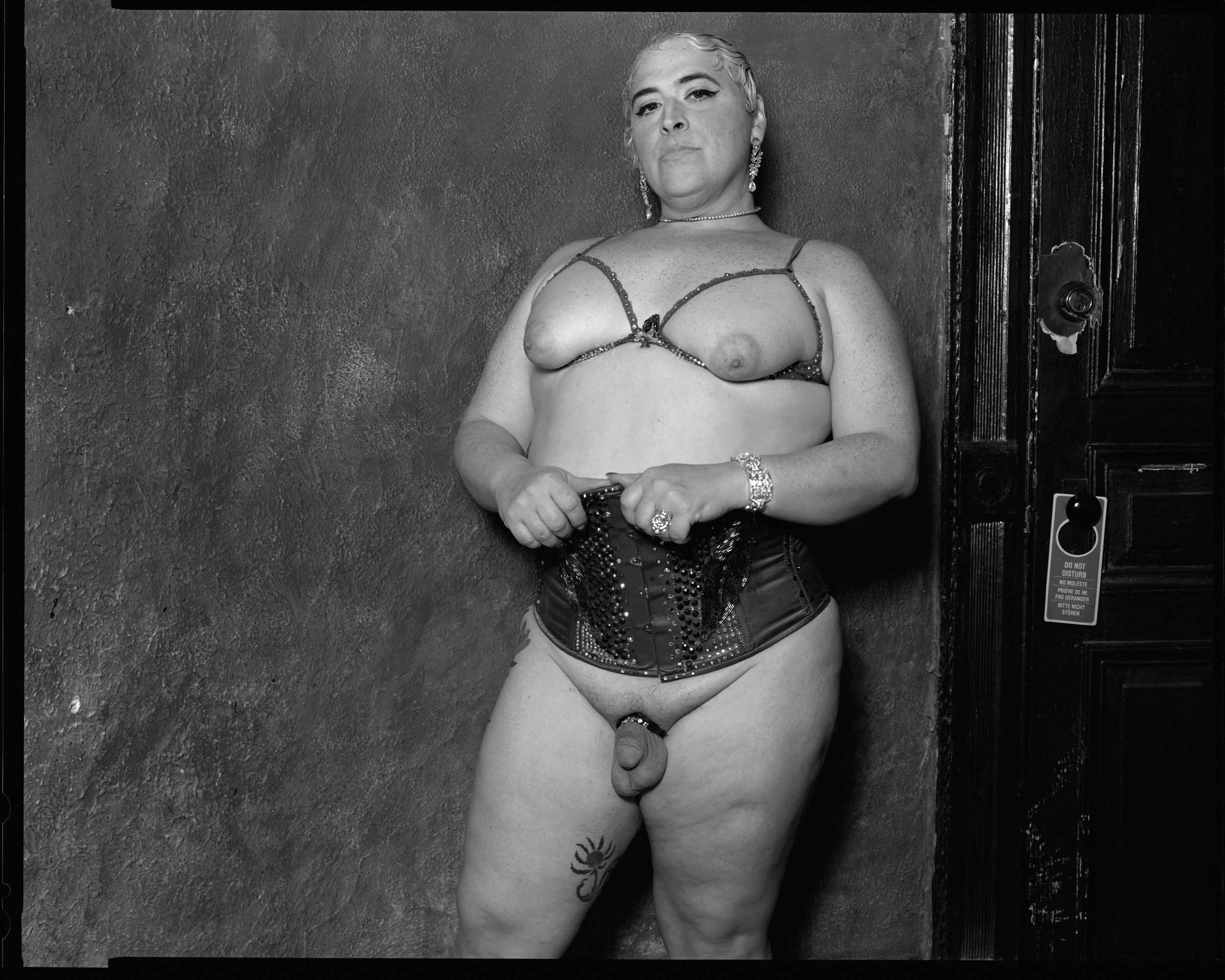

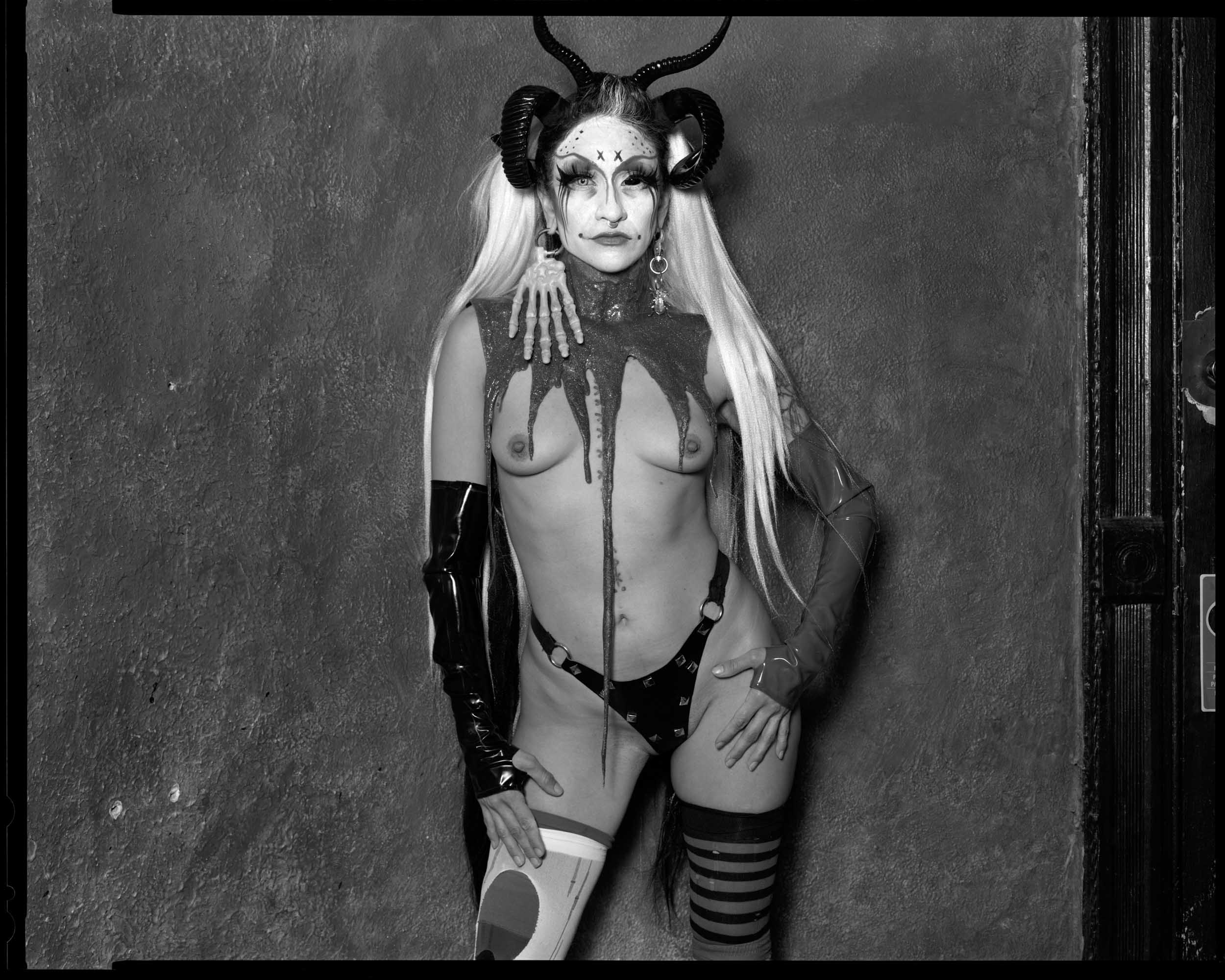

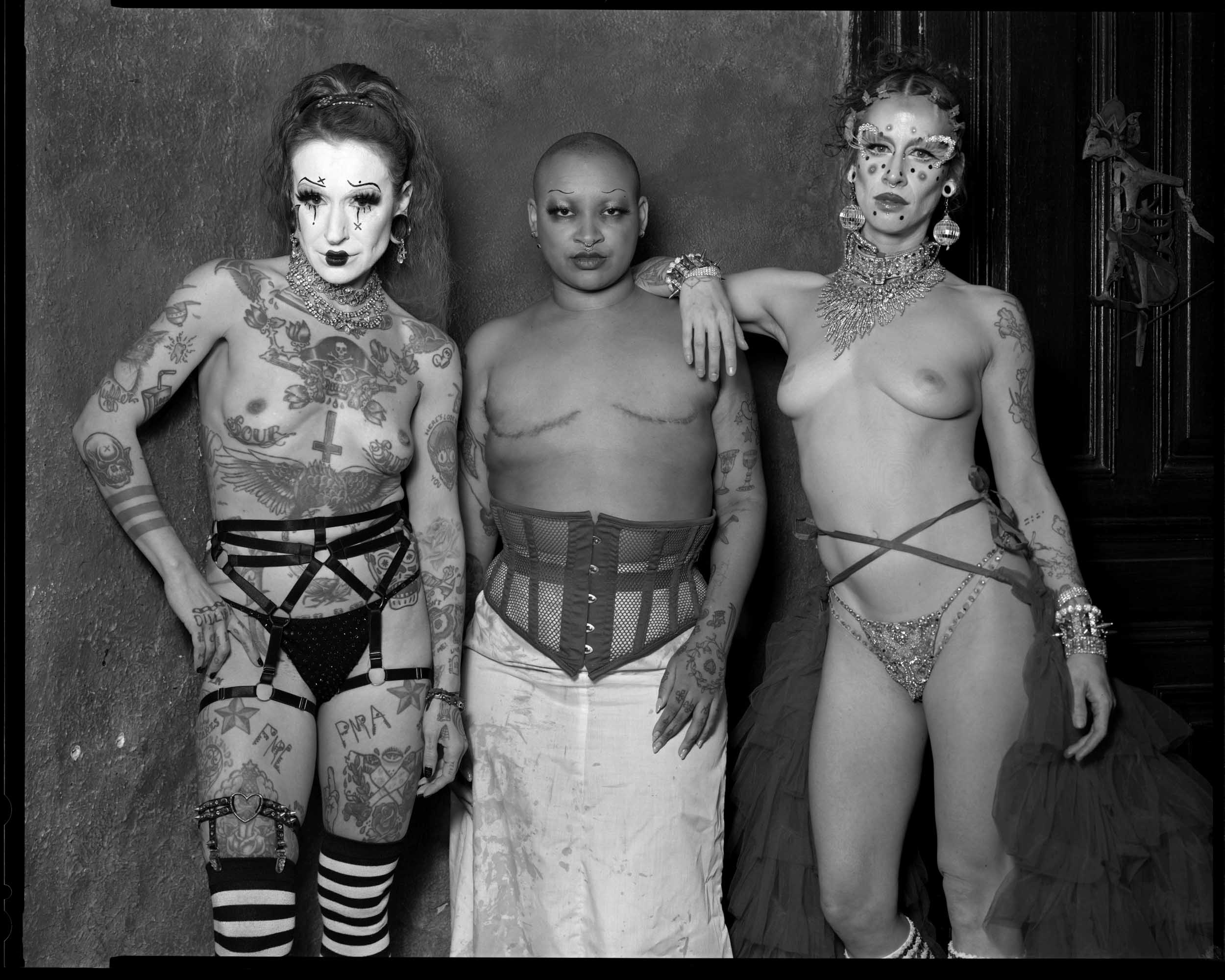

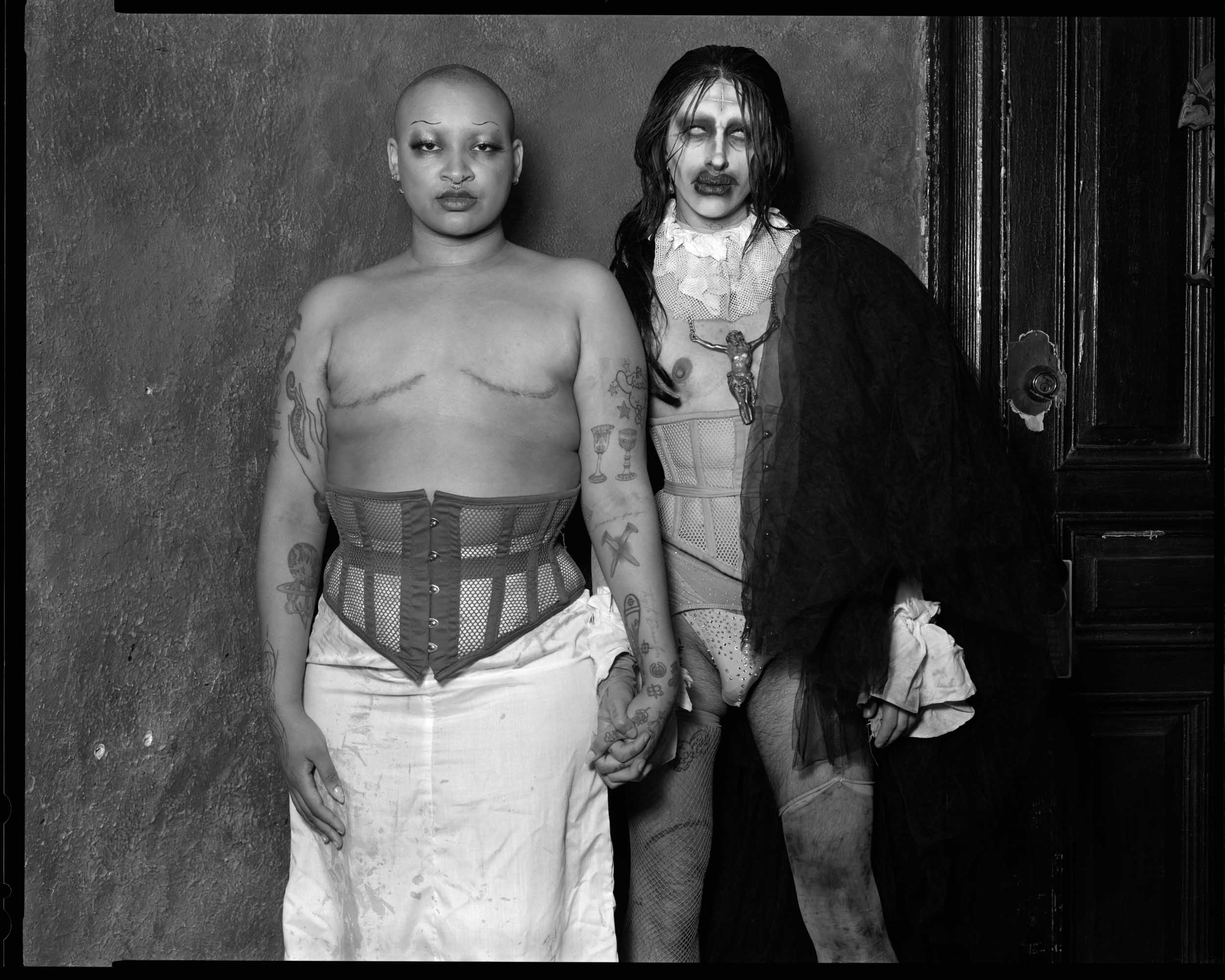

These days, a majority of the hotel’s rooms are now freshly-renovated and occupied by paying guests—but Notarberardino’s sixth-floor apartment remains untouched. With its celestial ceilings and colorful murals, the historic space is steeped in history and furnished with the bohemian splendor of another era—but in his Chelsea Hotel Portraits, Notarberardino isolates his subjects against a single wall, capturing the vibrant spirits of the hotel in stripped-down black-and-white. Shot using a large-format camera permanently stationed in his living room, the series is a timeless record of the people who made the hotel what it was, captured by someone who fell in love with it and never left.

In this exclusive portrait series for Document, Notarberardino now turns his lens toward the queer nightlife performers who are keeping the Chelsea Hotel’s subversive spirit alive, even as it changes around them.

Allegra Meshuggah (“which is Yiddish for crazy”), she/her

Professional clown, performing “since always,” working in nightlife for seven years

Camille Sojit Pejcha: How did you find your way into this line of work?

Allegra Meshuggah: All through high school, I was performing—then, as an adult, I was out in the real world for a while and realized I was feeling empty. I was like, Oh no, it turns out I need to be onstage. So I started working in nightlife, and when I moved to New York, a friend was like, You should go to House of Yes; the owners did not respond to his message introducing us, but I went to the club anyway and forced myself upon them. I was like, I’m volunteering. I’m gonna do this show tonight. I’ve worked there for seven years now, and I ask them constantly, Why did you let me do that?

Camille: What brings you the most joy about what you do?

Allegra: The community. I always felt, growing up, that the people around me didn’t get me, and I didn’t get them. Then I got into nightlife, and I was suddenly on the same wavelength as an entire room of people. I’ve always been a creature of the night, and I feel lucky to have stumbled my way into getting paid for it.

I’m also a longtime Burner, and Burning Man is usually about experiencing what you don’t get in daily life, so a lot of people put on crazy clothes and do crazy things—but when I’m at Burning Man, I put on my day clothes like drag, and I work in the production office, where I can support other people’s performance. Everyone wants to be a star, right? And the people who do it for a living, we are the outliers.

Allie Saint Surreal, she/they

Circus sideshow and drag performer, working in the industry for three years

Camille: How would you describe your performance practice?

Allie Saint Surreal: I’m a drag queen, but I also do a lot of the circus sideshow acts. I’ll staple money to myself, or skewer myself with needles. I do lego-walking sometimes. I’ve done animal traps here and there.

Camille: How does your relationship with pain change during performance?

Allie: When I’m onstage, it’s easier to bear pain because I’m entertaining, and the reaction I’m getting outweighs it. The pain you perceive is just something your brain is doing to tell you to stop, because you could be in danger—but if I’m onstage and I’m stapling myself and people are screaming because they’re enjoying themselves, I don’t want to stop, and my brain doesn’t really turn on that feeling.

Camille: What brings you the most joy about your work?

Allie: Doing drag lets me really get comfortable in my gender expression. Out of drag, I’m a very masc-presenting nonbinary person who goes by they/them; I don’t know exactly what it is to ‘look’ nonbinary, and I don’t want to have to walk around with a name tag. But performing at the Chelsea—the community that comes with this space, and the growth that it allows—has given me the freedom to really be myself. It’s not just a room of people who paid a ticket to see something entertaining; it’s a community of people who are all here to enjoy each other and be supportive, and that allowed me to slowly come out of my shell. With performance, you get to present exactly what you want to present; you’re like, This is my gender identity. This is how I want to be perceived.

“I love my work; it’s in my day-to-day experience as a trans person that this world makes me feel like shit. People look at me and see what they want to see, and it’s through performing that I have an opportunity to control how the world perceives me.”

Anna Monoxide, she/they

Professional clown and sideshow performer, working in the industry for seven years

Camille: What brings you the most joy about your work?

Anna Monoxide: Being able to physically do the things that I do. I had a back injury in 2015 that pretty much crippled me until I had surgery, so being able to move and do anything with my body is huge and it brings me a lot of joy.

My work includes acts like human pincushion, where you skewer your body with sharp objects, and human blockhead, where I nail sharp objects into my face. I also do wax-pouring, balloon-swallowing, and bend steel rebar with my body. For me, it’s something of a spiritual practice, and it has its roots there historically, as well. In India, there’s a type of person called a fakir, which is somebody who transcends pain to reach enlightenment: those who lay on beds of nails, walk on hot coals, or put skewers through their body. There’s the idea that, through the practice of handling that pain—learning to slow your breathing and heart rate, and be calm in the process—you reach a higher form of enlightenment.

I also do hook suspension—putting sharp hooks in your skin and hanging from them, which is a very old practice. The first mention of it I saw was in a Native American ceremony; the idea was that you would then be rigged up to a tree with wooden sticks through your chest, and you were supposed to hang there until the skin ripped—which often took days. Then, the ritual was over, and you would be a much more enlightened person. The first time hanging, it feels like your skin is going to rip off; I was like, I can’t do this. And the friend who was putting me up was like, You are doing this; your feet are already off the ground. You just need to calm down. And as soon as I relaxed, the pain went away.

Camille: What’s a common misconception about sideshow?

Anna: At other venues, people constantly think what we’re doing is fake; they think that you don’t really swallow the balloon when you do; they think that somehow I have fake skin that I’m piercing through. People think that the bed of nails isn’t sharp. People think that the objects collapse when I’m nailing them into my nose. When I do rebar bending, I bang it on stage to show that it’s steel—but people still think it’s soft. I had somebody ask me once after a wax-pouring act, ‘Was that hot wax?’ It scientifically makes no sense!

I think it’s because, if someone can’t imagine themselves doing it, they’re like, That’s impossible, that must not actually be happening. But a lot of classic sideshow performance is about just that: Training your body to do impossible things. I think that the way we present it is very artistic, and it brings me joy to present something like a pincushion act to opera music, and make it more accessible to people by helping understand that we view it as a form of play.

Camille: Tell me about your first experience at the Chelsea.

Anna: The first time I first walked in here, I remember being surprised there was no stage—but then, watching people perform, you realize you don’t need it. If you look closely, you can see that, on the part of the floor that becomes the stage, the wood is worn because so many things have happened right there.

It’s intimate. It’s magical. There’s just a certain feeling here. It’s very haunted, but in a very good way. Performing at the Chelsea is like feeding the spirits of the hotel so that the magic of the place can stay alive.

C’était BonTemps, he/him

Drag queen, working in the industry for 10 years

Camille: How’d you find your way into drag?

C’était BonTemps: I started in the South, where I was living as a drag king—and eventually, that turned into realizing I’m trans. And as I transitioned and got more comfortable in my gender identity, I left the masculine side of it behind and started performing as a drag queen.

Camille: How is the Chelsea, and the people here, different from other venues where you perform?

C’était: It’s just a whole different world. The first time I performed here, I was like, Whoa, this is very New York of me! And then, as connections grew between the other performers and Tony, it became this safe haven. You start to feel like you have a choice of what you want to experience together with everybody in the room, and you know what the audiences want, because we’re around friends. We knew we were all gonna hype each other up, and that we’re all here for something weird, something we can really sink our teeth into.

At the Chelsea, nudity is both overrated and underrated—you can perform a sexy strip tease or take your shirt off and just not worry about it, which gives a sense of disinhibition to the whole night. You can really do anything you want, and as a performer, that gives you the freedom to experiment with new things. In a way, you’re either super comfortable or super vulnerable when you perform here—the space will tap into whatever you’re feeling. There’s also a heightened level of engagement and support in the audience. The truth is, you’re not in the room if you’re lukewarm about this; if you felt lukewarm, you would have never gotten in here in the first place.

Camille: What do you find most freeing about your work?

C’était: As a drag performer, the only thing that I need to come in with is a song; everything else is an open-ended question of, What are you gonna do with that lip sync? The medium I’ve chosen is drag—but the possibilities are endless.

For me, anything I integrate into my performance has to have a narrative that goes with it; for instance, I’ve done a pincushion drag act to ‘four ethers’ by serpentwithfeet, and I integrated needles to show how every pinprick of insecurity, or every loss of a lover, leaves a scar. Some performers focus on the physical feats, but for me, the pain is a path to catharsis that feeds the emotion of what I’m doing. The body is this extreme instrument that can take so much, and you’re watching someone put needles in their body and conquer the pain. You can either hyper-focus on the needles, or see the bigger picture. In the same way that people like pain when it melds with pleasure, I like pain when it melds with narrative.

I want to marry whatever is happening to drag, so I try to use performance to get my most intense feelings out in a way that’s accessible, both for the audience and for me. I like talking to people afterward; sometimes it makes me cry, hearing what they were thinking about, and how it relates to my own story. We’re coming to realizations together, meeting at the same level at the same time.

Camille: What’s a common misconception you’d like to push back against?

C’était: For drag, the misconception might be that we’re bringing our kids to Hotel Chelsea! Just like any art form, there’s NC-17 and there’s G—and if you choose to take your kid to an NC-17, I hope nobody lets you in. And if you take them to a G-rated one, there’s nothing worse in it than what they see online! I’m not going to put needles in my skin in front of a two-year-old.

On a political level, these misconceptions have such a huge impact, not only on drag, but on trans people—because when you outlaw dressing as the other gender, it’s like, Fuck, who are you to decide who I am and what my gender is?

Another misconception about drag is that it can only be done one way. I could pick out 10 performers right now who are doing drag differently from one another. But I think people have this picture in their mind of RuPaul and Lady Bunny—which is beautiful and great, but it’s not the full spectrum of drag.

“Performing at the Chelsea is like feeding the spirits of the hotel so that the magic of the place can stay alive.”

God Complex, he/they

Performing since childhood, working in drag and nightlife performance for five years

Camille: Tell me about finding your way into performance.

God Complex: When I started doing drag, it was the first time in my life that I’ve done something and knew instantly that it was a thing I should keep doing. I started as a drag king; but since then, my practice has really shifted toward something a little bit less codifiable, in the nebulous space between drag and burlesque and sideshow and circus and performance art.

I’m lucky enough to be able to live inside of multiple communities and worlds in the nightlife scene; the world of burlesque and of sideshow, and also of explicitly queer Brooklyn drag. When I’ve been doing that kind of thing in front of those more classic queer drag audiences in Brooklyn, I often get the sense that people don’t know what to think. They don’t dislike it, they just don’t know what to make of it, because even as there’s been more acceptance for drag, it’s also directed toward its more homogenized form.

Camille: What was it like, the first time you performed here?

God: I am one of those people who’s so obsessed with the period of time in New York when the Chelsea Hotel was thriving—so being able to be here and be part of it is amazing. It’s funny, I remember being in my very early-20s and being like, Damn, I just wish that I was around at the same time as Robert Mapplethorpe… I think I could have been part of that world. And then ending up here and you’re like, We are the same. We are just the legacy.

I’m sure other people have said it, but it’s completely void of time here. The environment lends itself to experimentation. I make something new every time I come, because I can factor in the space that’s already there, the world, the set, where everyone’s mind might be—and also the fact that anything that goes on here, in a way, doesn’t really exist in spaces outside of this. The space can accept a lot riskier types of performance, because the people who are here can take that on.

Alaska, he/they

Sword swallower, aerial artist, and circus sideshow performer, working in performance for five years

Camille: What brings you the most joy about your work?

Alaska: I like to tell stories with my body, and I love the mutual emotional climax that happens during performance. When I finish an act, and feel that the people who I performed for—whether it’s one person or a thousand people—went through the same emotional journey with me. That is better than drugs.

You come to New York because you wanna find your chosen family, right? When I walked in here for the first time, it was like entering another world. I immediately felt at home; there was a sense of, Oh, I can just exist here. I do believe that everything contains its history, and at the Chelsea, you feel it; the stories of the artists that have been here, and the artists that are here now, just fill the space with an energy that is encouraging and safe, but also challenging—because here, I’m performing for my peers.

Camille: What are some common misunderstandings about your line of work?

Alaska: I went to the bar to get a drink the other day after sword-swallowing, and this woman came up to me, body-slammed me, and started calling me a freak. I think there’s this conception that sideshow performers are just out here to trick you and take your money, and that what we do isn’t worth anything. But performing is what gives me the freedom to be myself. I’ve found myself through this art form; I’ve always taken it day by day, or actively wanted to stop existing. But now, it’s been so long since I have not wanted to live.

Lola Strange, she/they/it (“if you may”)

Burlesque, fire, and sideshow performer, working in the industry on and off for 19 years

Camille: What’s your favorite part about performing for a living?

Lola Strange: I’m just so grateful that I get to express myself. At first, I repressed my desire to perform, and tried so many different jobs—but I’ve grown so much from following my instincts and just doing what feels right.

Performing is challenging in so many different ways; physically, I am facing my fears, and inspiring other people to do that, too, whatever that might mean in their life. I think it’s really cool how your body can sustain feelings of pain, and it’s okay; testing those limits makes me appreciate my body and my mind so much. Here at the Chelsea, there is a deep sense of love and connection that we’re sharing—because, as a performer, I’m trusting everybody in this moment, with my body. It’s very up close and personal. The space, the history, the energy, the people who are in the show and who come see it, are really special and beautiful. I’ve performed things at the Chelsea that are so physically challenging I can’t even practice them at home—I need the energy of the crowd.

“Anything that goes on here, in a way, doesn’t really exist in spaces outside of this. The space can accept a lot riskier types of performance, because the people who are here can take that on.”

Veronica Viper, she/her

Burlesque performer, working in the industry for six years

Camille: What was your pathway into burlesque?

Veronica Viper: Well, I’ve always been a performer of some kind, I’ve always been a maker of some kind, and I’ve always been a pervert of some kind—so I found burlesque and I was like, Oh, I can encapsulate all that into one creative medium. And honestly, I love my work; it’s in my day-to-day experience as a trans person that this world makes me feel like shit. People look at me and see what they want to see, and it’s through performing that I have an opportunity to control how the world perceives me.

It’s important to be visible with all that’s going on right now, and I make a lot of effort to be in places that don’t typically see women like me. Unfortunately, just me being sexy onstage is transgressive, which pisses me off! But also that means that it’s the perfect opportunity to just be who I am, knowing that for any trans woman to take her clothes off onstage is radical. My existence is illegal in several of the states of my own country, and as a born-and-raised New Yorker, it’s a hard concept for me to wrap my head around. It’s a head fuck, and in return, I make it a mission to get on stage and fuck with people’s heads.

In many of the places that I’m performing in—the Chelsea Hotel excluded—there’s gonna be a portion of these audiences who have literally never seen a trans person. So it spans a wide gamut, in terms of what they’re going to take away from that experience. As a trans person, my performance gives me a moment to control what message the audience receives about who I am—so that, for me, feels really powerful, and that’s why I pursue it. Drag and burlesque are the same in that sense; in drag, you put layers on to reveal your true self. And in burlesque, you take layers off to reveal your true self—but the underlying message is the same: This is me.

The amazing part about performing at the Chelsea is that I’m performing for my own community. These are the same artists that inspire me to keep going, and then I get to share the space with them. That process alone is incredible, and the Chelsea is a rare experience of that—because you really do get the finest performers in the world, just passing through. It’s profoundly special. It’s one thing to be a working artist in New York City and have your art appreciated by the general masses, but it’s another thing to have your art appreciated by other artists. And you know that the group that you’re gonna get here are gonna be connoisseurs.

There’s a special energy at the Chelsea; the sense that we are going to do something now together, and that this is an exchange—it’s not just a performer up on a pedestal. You can really feel it in the room. If you’re the type of person that I am, and you like to get naked in front of strangers, it’s a wonderful place to do it. The audience needs me and I need the audience, and there’s something symbiotic that happens there in that moment. And not only do I get to portray myself in a certain light, [but] I also get to be expressive and creative and powerful and sexual and radical and whatever the fuck I want to be—and I get to make a little tiny bit of my living from it, because, after all, This is New York.