From the prop room of his upcoming feature ‘The Visitor,’ the shock connoisseur talks Pasolini, religious ecstasy, and the true ethos of experimental art

I’m standing in the prop room for arthouse director—and notorious shlock and shock connoisseur—Bruce LaBruce’s latest movie. A table is laid with penis prosecco glasses, a dildo with Jesus on the cross as its handle, and a plate of fake feces. The Visitor, the film to which they belong, will be released in late 2023—an ode to one of LaBruce’s favorite filmmakers, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Specifically, it’s an interpretation of the Italian auteur’s 1968 film Teorema (Theorem), starring Terence Stamp as a mysterious stranger who shows up at a bourgeois Milanese family’s doorstep, and begins to wreak havoc on their lives, freeing them from their repressed ways in the process.

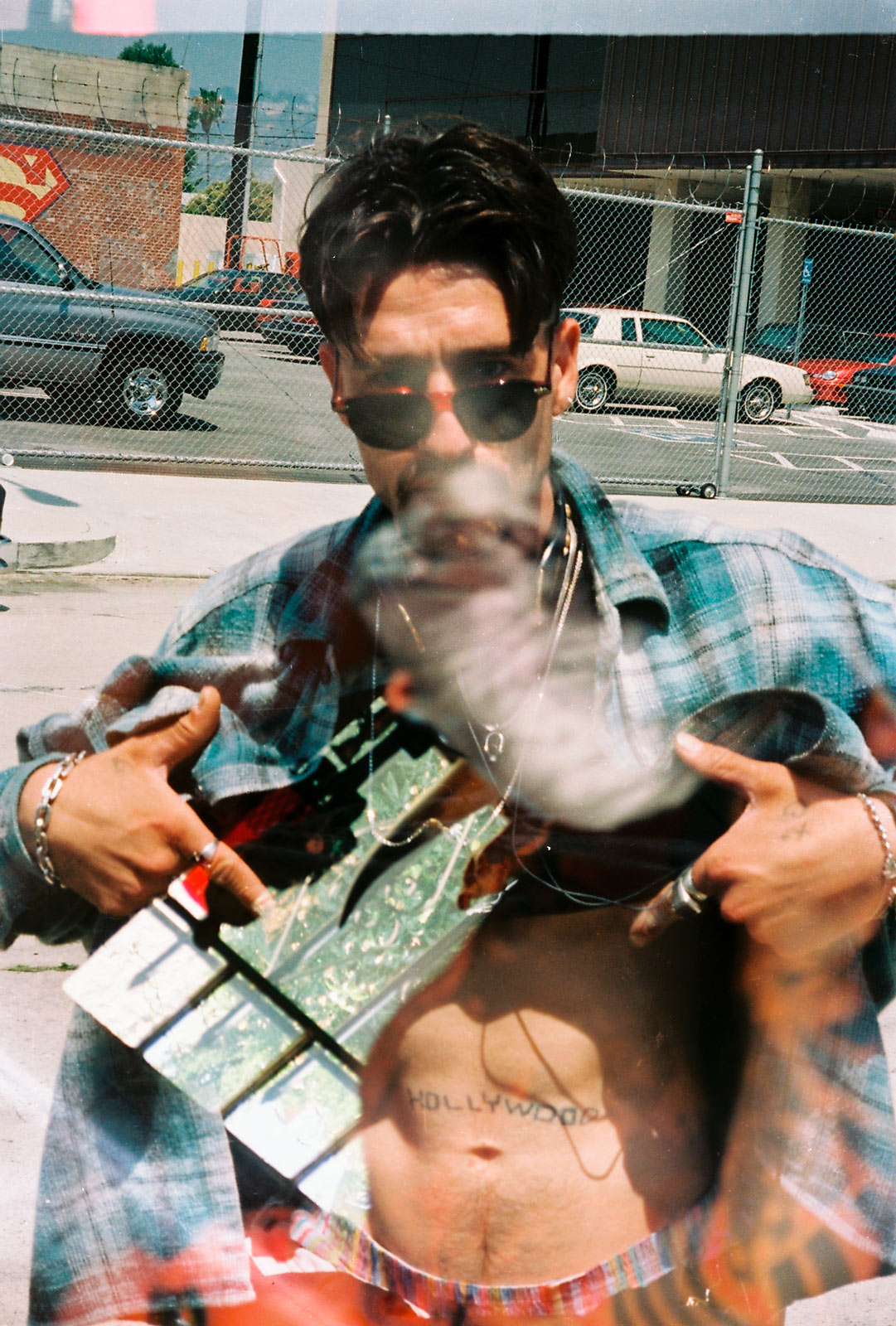

LaBruce enters wearing a John Waters t-shirt, overlaid with a heavy black one that reads BASTARD across the back. On his fingers, his trademark gold rings, designed in collaboration with Jonathan Johnson. Today’s read c*nt and daddy, as well as love thyself—a reference to LaBruce’s 2020 “twincest” movie, Saint-Narcisse. He gives me a rundown on the rest of the props, explaining that The Visitor follows the story of a refugee who washes up in London. A sexually-explicit romp ensues. In fact, a few days before this meeting, LaBruce invited a public audience to watch him shoot where we stand now: the South London base of radical arts organization a/political (who serve as the film’s executive producers). Guests peered through peepholes as LaBruce directed live sex scenes—specifically, featuring the characters of the father, the daughter, and the visitor himself.

It might all sound outré. But by LaBruce’s standards, it’s par for the course. Over his three-decade career, the Canadian director has pushed the boundaries of bad taste into entirely new dimensions: Neo-Nazis, incest, torture, and gerontophilia are just a few of the subject matters that have received the LaBruce treatment. Like Pasolini himself, he’s been both outlawed and lauded. LaBruce’s film L.A. Zombie was banned from the Brisbane Film Festival, and Saint-Narcisse is blocked from Amazon. At the same time, he’s been featured in retrospectives at both MoMA and the Toronto International Film Festival. Talk about c*nt daddy behavior.

After LaBruce shows me a few “piss paintings” from the making of The Visitor, we sit down for a conversation about his new movie, the legacy of Pasolini, and his transition from DIY punk cinema to studio work—and back again.

Amelia Abraham: Firstly, what’s a piss painting—and why am I looking at one?

Bruce LaBruce: In Pasolini’s Teorema, the son is trying to break out of conventional [artistic] methods after being liberated by the visitor—so he makes piss paintings. There’s a copper plate on the canvas and the copper oxidizes. We recreated that, but our actor’s pee was very prodigious, so we may have the longest pissing scene in a film, ever. We’ll use the full cut. So I’m riffing on Teorema, but in my version of Pasolini’s film, the stranger shows up to a bourgeois family and ends up having sex with them all.

Amelia: Tell me more about The Visitor. In what other ways have you adapted Pasolini’s film?

Bruce: In Teorema, the daughter—for some reason—goes into a coma. It’s a transcendent state; she’s catatonic. In my version, she gets pregnant, and the visitor is a refugee who arrives in a suitcase—literally naked, in a raft, on the shore of the River Thames. Actually, I forgot about the tide situation, so we ended up having to throw our equipment over the wall to save it. In Pasolini’s original, the visitor is never identified; he is a crisis figure-cum-sexual healer. It’s implied that he liberates each of the characters in this repressed, bourgeois family through sex.

I always felt that was a perfect scenario for porn. Then, I thought, If we’re updating to a contemporary context, it would be relevant to cast the visitor as a refugee. It’s partly about the context of shooting in the UK: the pitch of racism there now, with refugees being sent to Rwanda and the US. The refugee is sexualized in a very problematic way—like with Trump, talking about Mexican refugees being rapists to drum up paranoia. It’s also working with myths about people from Africa [being] sexually-primitive avatars, and how that’s both a fear of the Other, and, at the same time, a fantasy some people have. This is something I play with in a lot of my movies: pornographic tropes that are very dark, or politically incorrect. The pornographic goes to those places—which is not to justify them. I am interested in how the sexual unconscious can be very unruly, and the id very unfiltered.

I’d wanted to do an update of Teorema for a long time. I don’t know Marina Abramoviç well, but I remember talking to her about it years ago.

Amelia: Would have been cool if she popped out the suitcase.

Bruce: Yes—or [out of] the daughter’s vagina.

Amelia: Last week, you invited people here as you directed the sex scenes. How did that go?

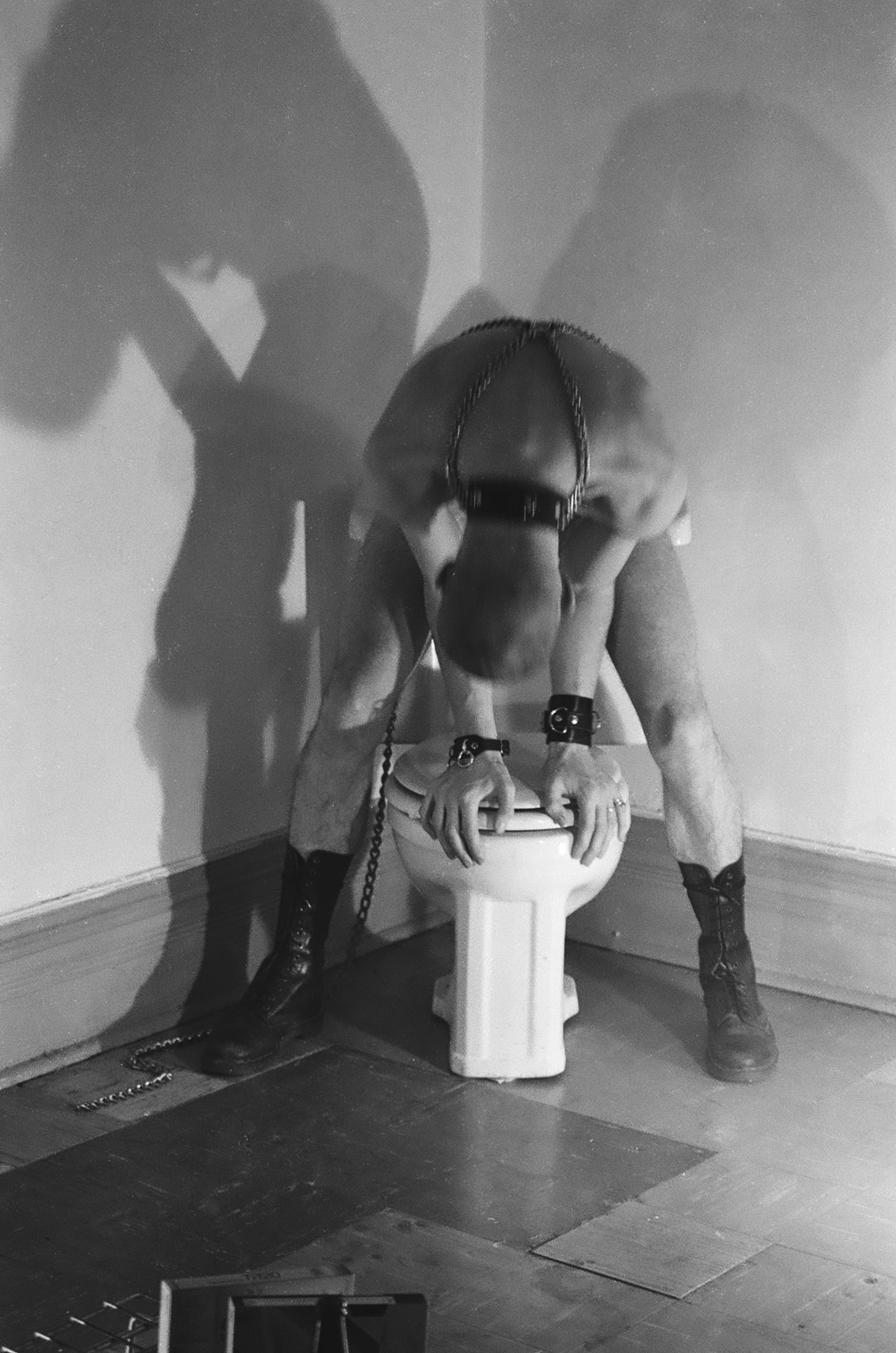

Bruce: I have a tradition of doing live performances at art galleries. It quite often involves an abduction and torture scenario—say, two people tied to a chair dressed as zombies or terrorists. I did one when Abu Ghraib happened. It’s referencing how the media displays these videos as entertainment—these slick beheading videos, as though they’re pornography or something. It’s about how violence is much more acceptable in the media or pop culture than explicit sex. Ten or 15 years ago, you’d rarely see someone getting murdered on the news. Now, we see it not just on the news, but on Instagram. I invite the audience to participate in the torture, and I take Polaroids. It has a playful atmosphere, deactivates the toxicity of it. But then I’ll get people to take it seriously, and make it look as real as possible. The live sex viewing was kind of in the tradition of those happenings.

“It may seem like a fetish is demeaning, or disrespecting the object of desire. But often, I find it’s a kind of worship. I try to find and appreciate the more spiritual aspect of it.”

Amelia: What’s your relationship with Pasolini more broadly?

Bruce: He’s the master. Pasolini and Fassbinder. When I was a film student, they influenced me the most. Both their films are about sexual domination and submission. Later, I did a theater piece in Berlin called Cheap Blacky, where I took four films influential to me: Teorema, Reflections in a Golden Eye, Whity, and Boom! In each case, there’s a character, who’s like a hustler, that comes to a family and fucks them all—a liberation and a destruction.

In his Trilogy of Death, Pasolini critiques the fascist people in power, who use sex to humiliate or control people while also being masochists. In Salò, they participate in the rituals of eating shit and getting sexually humiliated; Pasolini’s saying that it’s not as simple as the powerful being dominant, and the people with no power being victimized. The sexual imagination is much more complicated—like the idea of the British parliamentarian, who likes to get spanked by a dominatrix or wear women’s garters. In Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life, sex is more about romanticizing the sub-proletariat. It’s more animalistic, but not in a pejorative sense: He equates the peasants with dogs, but as the purest creatures. He has this Spinozian philosophy that God exists everywhere—in the most mundane and common people and places.

Amelia: When did it occur to you that pornography was a medium you wanted to work with?

Bruce: I’ve always used porn in what I consider to be a political way. When I was a queer punk in the ’80s, we were disillusioned by mainstream gay culture. Mainstream, middle-class, white, gay culture was very racist and sexist and bourgeois—so we turned to hardcore punk. We thought it was more politically radical, and interesting aesthetically. Only, we found the same problems—and, as a bonus, homophobia. So we started making these very queer, explicit films in a punk context, to make the point that punks weren’t as politically radical as they thought they were. If you can’t see two guys fucking each other up the ass, you’re just as sexually repressed as the dominant order. From that moment, it became a political statement for me to use extreme queer porn.

Amelia: You deal with fascism a lot. Why do skinheads interest you?

Bruce: That comes from personal experience. I dated this guy—my first boyfriend. He was a hustler. He had a No-wave kind of style and philosophy. We broke up, and I ran into him two years later. He’d become a neo-Nazi skinhead, with a shaved head and tattoos, spouting neo-Nazi bullshit. But he was homeless, so I let him stay with me a month, and we were having sex again. I was trying to reason with him—telling him how ridiculous it was, what he believed in. One day, he beat the shit out of me outside my house. That sparked something in me: about the contradiction of having highly-sexualized feelings for something I found repugnant politically. Knowing someone on a personal level, and being in love with them, and having to cope with that disconnect where they come to represent something you hate. That’s where the skinhead fetish came in. In terms of my own sexuality, now I tend to be very submissive, and my fantasies are often based in domination and humiliation.

Amelia: What about fetish?

Bruce: In the last 10 years, I’ve made a lot of work with religious iconography. I think we can draw a parallel. I did a show in Madrid in 2012 called Obscenity, about the intersection of sexual and religious ecstasy—particularly in the lives of the saints, which are riddled with instances of fetish. Not just the brides of Christ, but the licking of the feet of martyrs, breasts chopped off, flagellation, self-abnegation. This idea that the material world prevents you from experiencing God, so the flesh is reviled. Ken Russell’s The Devils was always a big touchpoint for me. I think what I find interesting about fetishes, is they’re an expression of devotion and reverence. It may seem like a fetish is demeaning, or disrespecting the object of desire. But often, I find it’s a kind of worship. I try to find and appreciate the more spiritual aspect of it. Most people have fetishes of one kind or another, yet they’re made to feel shameful or perverse or base.

Amelia: As a queer person, I can clearly see fetish as pursuing your desire, despite the stigma and shame attached… I am sympathetic to ‘divergent’ sexualities.

Bruce: Yes—because fetish challenges the boundaries of sexual conversations, and what is considered acceptable.

Amelia: As do your films.

Bruce: My films are about: Where is that boundary, and how far can you push it? In this project, there’s a lot of incest, and I’ve been playing with that lately with Saint-Narcisse. I took a lot of psychoanalysis in university, and there are Freudian ideas that interest me—like the family romance, the idea that there are all these sexual tensions between members of the nuclear family, and you’re supposed to ignore them. People don’t talk about it, but then they marry people who remind them of their father or mother. Or, there was a study done about members of an immediate family separated at birth. It found that there’s often a strong sexual or romantic connection between them, if they reunite. They sense that familiarity.

I always thought that twincest was the most understandable or acceptable form of incest, because most people can relate to the idea that—if you had a replica of yourself—there would be a kind of sexual attraction.

Amelia: I had a twin that didn’t develop in the womb. I do sometimes wonder if I am searching for them romantically.

Bruce: Or maybe you are your twin. There’s a thing where twins merge in the womb. If people have different colored eyes, it can be attributed to that.

I think there’s two kinds of people in the world: people who are looking to fuck themselves, and people attracted to the exact opposite of who they are. I’m more the latter. But you see the former all the time in the gay world. We call them twinnies—those boyfriends who look identical.

Amelia: In dyke world, we call it the ‘urge to merge.’

I wanted to ask about the humor in your work. I was revisiting your film The Raspberry Reich recently, and there are some hilarious lines: ‘heterosexuality is the opiate of the masses,’ and ‘join the homosexual intifada.’ Are you trying to be funny? How do you engage with camp?

Bruce: Camp is a big element in all of my films, and John Waters is a big influence. But sometimes, the best camp is played straight—so that’s what I tried to do with Saint-Narcisse. It was a bigger-budget movie, very narrative, and I cast professional actors. It was within the tradition of Hollywood melodrama. You’re not nudging or winking at the audience. They’re meant to take it seriously, in a way, and that’s even more camp. But actually, humor is a great political strategy, because it gets people to let their guard down when you’re dealing with extreme subject matter. I’ve been told I have a light touch, which I do instinctively.

For a second, I was concerned The Visitor was too serious. On the first day of shooting at this huge mansion, there was a scene where I have the family eating shit. They start out not into it, and smelling it, and as the scene goes on they taste it and get more into it. They’re licking their plates in orgasmic pleasure. I was laughing so hard behind the camera. It was an outrageous scene, and I thought, Okay, I don’t have to worry about the humorous elements of the script. They were there; they just came out in the filming.

Amelia: Is it hard to shock people these days?

Bruce: It’s kind of hard these days. You see everything now, on the internet. Things you don’t even want to see. We’re in an age of maximalism.

Amelia: Like an unsolicited dick pic on Grindr, or a beheading on Instagram.

Bruce: Right. You’re bombarded. There’s a weird schizophrenia where pop stars look like strippers—they have for 10 years, and yet, there’s a temptation to be prudish about sex. A puritanical swing. Marvel movies—so sexless. Everything’s desexualised because of markets; because there’s something they’re trying to sell to China. I’m interested in pushing against that.

Amelia: How do you continue to challenge yourself as a filmmaker?

Bruce: This whole scenario has been a good example. I made a couple of films now in Quebec that were union films—done in a professional way, they have a protocol. To switch gears from that, and go back to my experimental roots, is very challenging. I came not knowing what to expect. I hadn’t seen lots of locations, or met the actors in person. The whole week was chaotic, and I was adapting things on the fly and reconceptualizing the script with the limitations I had. That took me back to my early guerilla style of filmmaking. Not being picked up at 7 a.m. in a SUV with a cappuccino. This wasn’t like that at all. It was a free-for-all. Back to the true idea of experimental filmmaking.