Alexander Konschuh joins Document to dissect the intentions, personal reckonings, and painstaking process behind the making of his stop-motion music video

The fear of being forgotten easily overpowers the stamina for true rumination, resulting in half-baked ideas and ill-executed work. For Alexander Konschuh—artistically known by the moniker Malice K—that undesirable urge for premature fruition is weighted by the hunger of the online ego and addiction to its short-lasting satisfactions. The Washington-born musician has consciously resisted that, in an effort to prioritize his own validation over that of his audience, and the impact of a project as a whole over piecemeal praise.

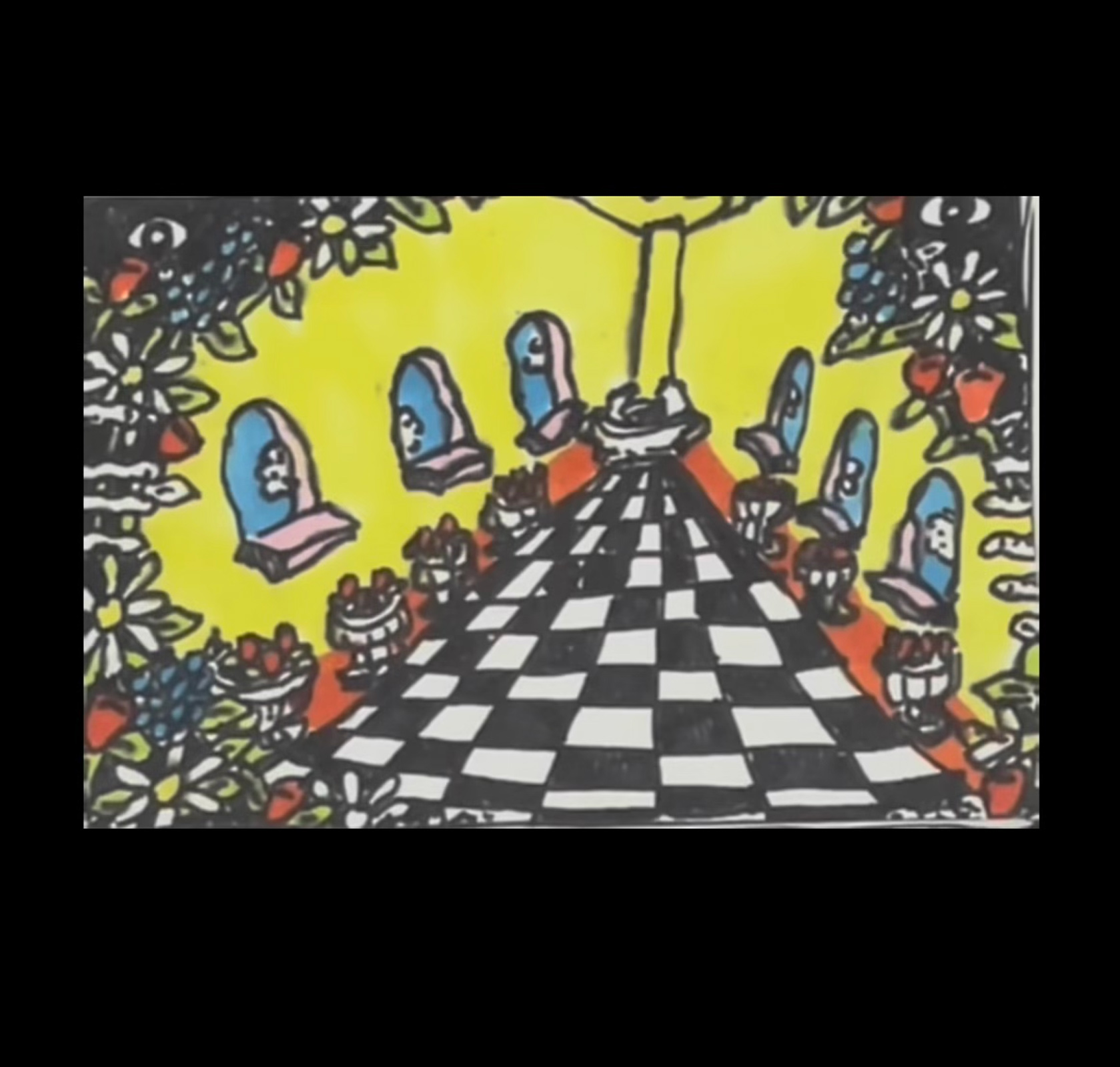

This old-school ethos served as the basis for the stop-motion music video for “Complicated Dreams (Myagi),” composed of more than 3,000 hand-drawn frames, painstakingly rendered over the course of six months. The drawings possess a childlike charm that calls back to the art of Daniel Johnston, interspersed with Polaroids set in sketched frames. The time invested in the video is its focal point; the many pieces that come together as a whole, and the willpower required to resist any one being set as a singular entity render the care put into it tangible. Says Konschuh, “I had to fight this sense that I was being forgotten as I worked on it.”

On the occasion of the video’s release, and following a Brooklyn gallery show that put its many frames on display, Konschuh joined Document to dissect the intentions, personal reckonings, and painstaking processes behind the making of “Complicated Dreams.”

Megan Hullander: How much of the video had you conceptually mapped out from the start, and where was there room for new ideas?

Alexander Konschuh: I had no concept of the video when I began. I just wanted something to invest my time in while I got off drugs, and back to health. I’d done some experimenting with animation in the past, and the tediousness of it—creating a world that you could lose yourself in—was alluring to me. I bought some construction paper and things at the dollar store, and just saw what I could come up with.

My stamina was pretty low for it at the start; the work felt grueling. I would want to stop, but it [was] difficult to let a sequence have no resolution or evolution. I’d be driven insane by how badly I wanted to show the video in its premature stages—to get validation for how much work I’d done already. But it was easy to foresee it giving me a sense of pseudo-accomplishment, jeopardizing my will to continue. During the six-month process of making the video, at times, I’d [finish] 10 seconds in a week. [And at] others, I’d make one second in a month. I had to put a lot of stress on my creativity to accomplish everything without special effects or post-production. Every millisecond had its own, physical Polaroid or hand-drawn, hand-colored slide. I had to [find] the middle ground, where my limited experience and ambition for the concepts met. It felt like an abstract math problem—making sure the physics [went] smoothly with the concept.

Megan: How do you contend with maintaining a social media presence, with that understanding of the warped ideals it can produce—as well as its threat to your real-life progress?

Alexander: I don’t like the idea of it. But when I think in retrospect, almost every show, sale, thrill, victory, and life-changing experience was brought into my life by Instagram. Only by default, but still. I’m just doing my best to be authentic and fulfilled while working with the outlets available to me.

Having nobody know about my art, and how hard I was working, made me suicidally insane. But having people know about my art makes me just insane, so I split the difference. I have two phones: an old iPhone that I can only use on WiFi, and a Nokia. Although it’s difficult to avoid social media, I limit my dependence on it. I don’t really take the iPhone anywhere I go. I never have the excuse that I need it. All this aside, I wouldn’t lose any sleep if the internet were to disappear.

Megan: Are there any artists whose work influenced the ideation of this project?

Alexander: It felt like it was all about me, and exploring myself through something new. I’d been influenced by some behind-the-scenes clips of Disney animations, but I wasn’t drawing inspiration from anyone in particular.

Megan: How many of the frames are displayed in the gallery space? In this format, what added layers of understanding do they offer your audience?

Alexander: Unfortunately, I threw away the first 20 seconds or so, so those slides will be missing. But the rest will be displayed at my gallery showing. Hopefully, seeing the craftsmanship and thought that went into it will serve as a silent protest to digital, algorithmically-fashioned, and AI-generated art. Many artists are compliant with the demand for consistent content, and value it over their projects. People are afraid to disappear in the swarm of posts, to lose their relevance—now more than ever. You’re not allowed to consent to what you see anymore, even if you wanted to: accounts you don’t follow, ads placed between every two posts.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to respect yourself [when you’re] selling your work in this format. You see a political debate, a comedy video, someone twerking, a hate crime—and somewhere in between all the madness, there’s your art. It’s less of a competition against other artists, [and] more against people’s attention spans, and their decreasing ability to appreciate things. It seems that the only thing that will work for both my sanity and career is to slow down, take a step back, and allow the work to speak for itself, for whoever is listening. I’d like to build a trusting relationship with my audience and the work I produce. They know it will be good, and they trust I’m hard at work despite my periodic absence. That just sounds a lot more romantic to me than being on top of the shit pile.