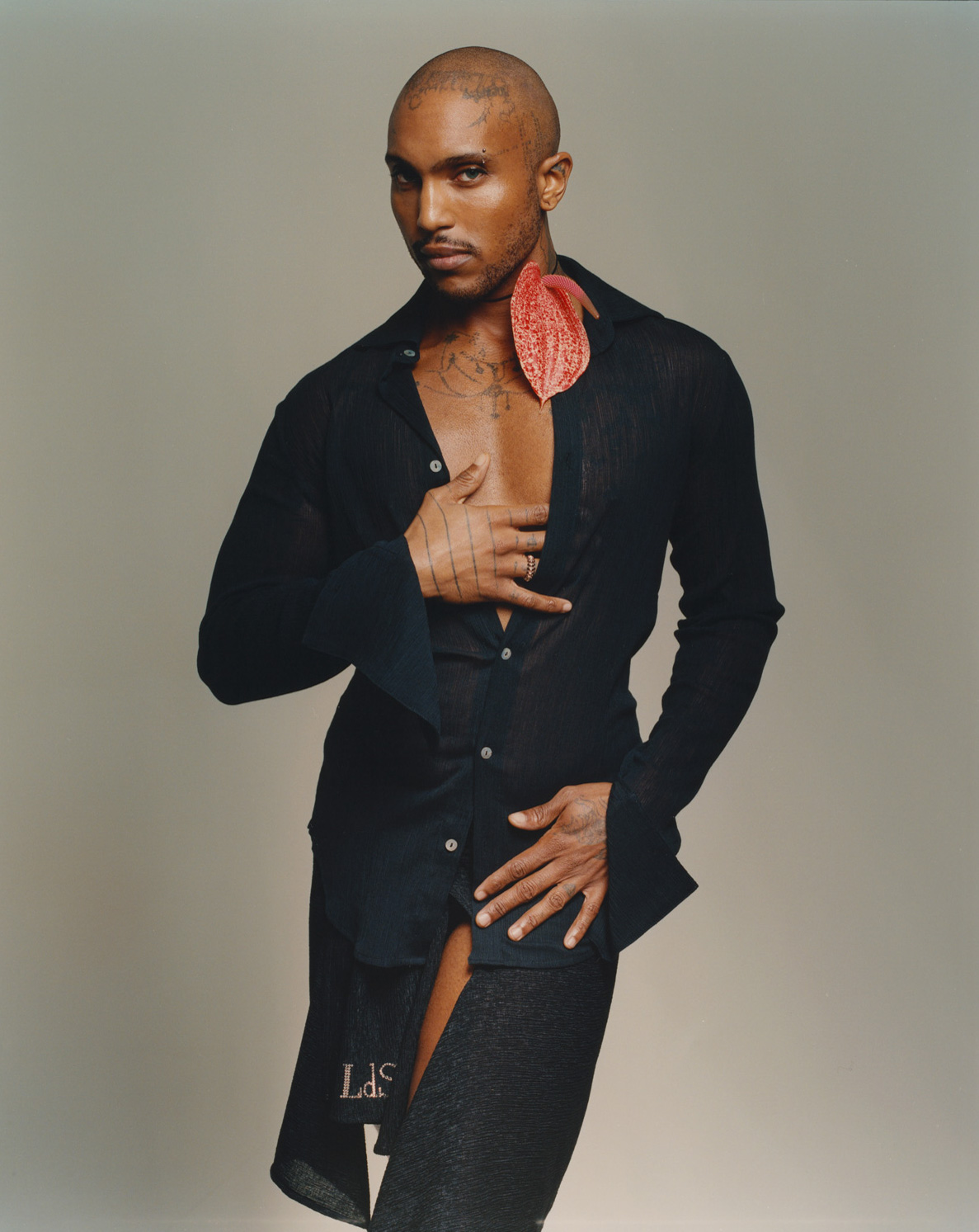

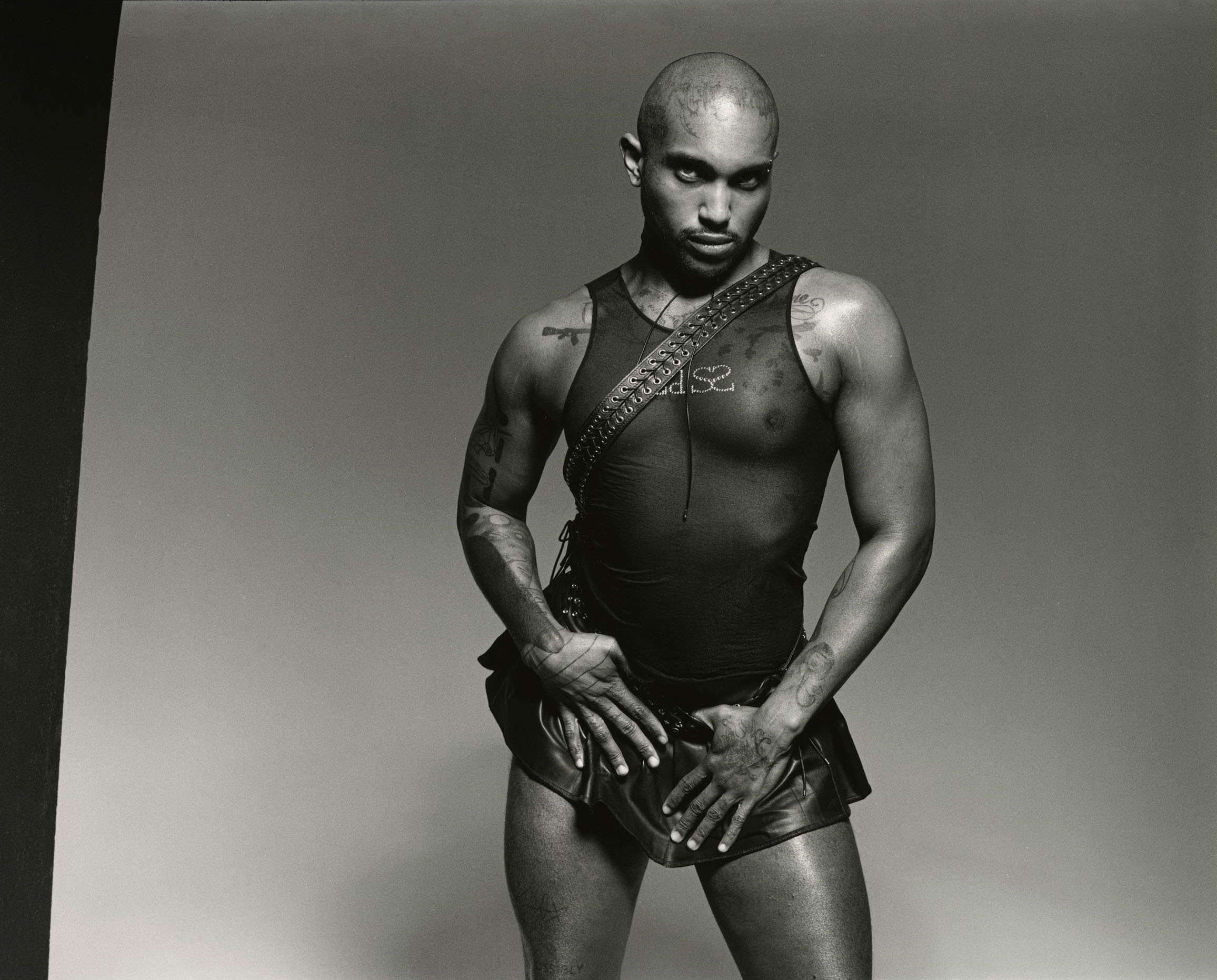

For Document’s Spring/Summer 2023 issue, RJ Glasgow divulges his aspirations toward idolatry, detailing his pursuit of the perversion of pop

‘I’m a sick bitch and I like freak sex / If you wanna test the limits of my gag reflex,” LSDXOXO sings amid a knot of writhing bodies in the music video for “Sick Bitch,” a frothy ode to fetish. In another, he sits on a pyre of burning embers as the words I’ll make the devil fuck me good skim across the bottom of the screen. But there’s a cute, almost cloying flip side to his lewdness. “DRaiN,” a pithy pop anthem shot from a bedroom set, presents the musician as innocent, almost adolescent; “You don’t return my calls / Even though I paint so many pictures of you / There’s no room on my wall,” he sings in the torch song that harkens back to the naïve romanticism of 2010s-era Taylor Swift.

The imagery from the artist’s archive of music videos is at once playful and deranged—a duality that sits at the center of LSDXOXO’s persona, which carefully balances submissive femininity with a sassy, shit-stirring alter ego. The character first emerged in 2013, as the Philadelphia-born producer—more intimately known as RJ Glasgow—began bricolaging mash-ups and Tumblr mixtapes. Raised in a religious Caribbean-Hispanic family, his first forays in music were confined to the Internet’s permissive ecosystem. He released homemade dance edits of nonconformist rock, pop, and hip-hop to SoundCloud while he was still living at home. (Think juke mixed with exquisitely lo-fi rips on Rihanna’s “Love Without Tragedy.”) It wasn’t until relocating to New York City after college and discovering other queer BIPOC artists like Cakes Da Killa and TYGAPAW—who tread similar techno-adjacent, club-music territory—that he started experimenting with his sexuality and pursuing a music career beyond the anonymity of the digital realm.

In early DJ sets at Venus X’s GHE20G0TH1K parties, Glasgow superimposed ribald samples with dips into juke, hardcore, and Baltimore club, earning a reputation as an innovative tastemaker in Brooklyn’s underground. And after a series of incendiary mixtapes helped him home in on his sound and shoot to local popularity, the artist ventured further into sample-based production. Like many aspiring electronic musicians, he moved to Berlin to broaden the contours of his creative identity. In an environment primed for both musical and hedonistic exploration, Glasgow’s career flourished, as did his growth as a self-actualizing person.

Upstream of the city’s reputation for humorless techno, the artist has evolved from creating floor-filling dance music sets to original releases and live performances that drip with irreverent allusions to Chicago ghetto house and tightly-packaged pop. His debut EP for XL Recordings, Dedicated 2 Disrespect, eschews his traditional use of samples for his own productions and voice. The foursome of queer banger tracks toes the line between seriousness and sleaze that has now become the artist’s trademark—four-four kicks bolster phone sex hotline-like telephone rings and ridiculous but catchy vocal refrains; high-tempo techno cuts whine with bubbly production and unadulterated camp.

Glasgow’s artistic maturity has allowed for a more elaborate and theatrical stage presence, too, indulging his affinity for highly aestheticized queerness and subversions of masculinity. Moving away from the comfort of the DJ booth, last year saw him perform choreographed live shows at Sónar Barcelona and Dweller New York, where he appeared corseted and decked in bejeweled headwear, crooning into the microphone. His output since—collaborations with Lady Gaga, Kelela, and Fever Ray—cemented his affiliation with the contemporary mainstream canon, facilitated by queer pop’s influence on dance music. He’s made no secret of wanting to become a figurehead for this crossover movement, to reimagine the once-classic intrigue of pop stars with contemporary sensibilities.

Now on the cusp of completing his second EP, a debut album, and a handful of forthcoming collaborations, the artist has a packed year ahead. Glasgow joined Document to discuss his burgeoning artistic evolution, aspirations for idolatry, and talent for bringing the fantastical to life.

Chloe Lula: What role does pop music play in your work?

RJ Glasgow: I find the relationship that pop musicians have with their audiences interesting—it reminds me of religious leaders controlling the masses. Music is super influential on our emotional states and how we interact with people. Because of that, pop stars have a lot of weight to push around. That’s one of the themes in this album: creating this character that is a bit less accessible.

A lot of the glamor and mystery [once] associated with musicians, or anyone in a creative field, has vanished because of social media. I don’t need my fans to know what I had for breakfast. There’s an air of mystery that I would like to maintain. I think idolatry plays a hand in that, because if you create this space between yourself and your audience, there’s always going to be mystery, and they’ll always want to know more. That’s kind of a power in and of itself.

Chloe: Do you feel like you’re playing a character?

RJ: While I do toy around with there being a character that I put at the front of my works, that character is a facet of myself. My default is actually quite reserved, and a lot of people, once they meet me, are surprised by my demeanor.

The character of LSDXOXO was made when I began [playing] around with the idea of being a musician and a vocalist. It was a bit of armor that I would put on—character-building as a means to protect myself and push myself to really engage with my audiences. Thankfully, I feel like I don’t necessarily need that character anymore.

Chloe: From the outside, this sense of exploration and self-actualization appears to have manifested through your music, and the creative renaissance you’ve undergone.

RJ: Moving to Berlin helped me to step into my skin as a musician and vocalist. In a city like New York, things are constantly happening, and it didn’t give me enough time to decide where I wanted to go next with my music. I was doing the same thing over and over again, because I was successful just being a DJ. I didn’t have anyone challenging me to do something more. Whenever I came to Berlin, I met people who were passionate about music-making, and just a bit more open to failure. In New York, you can’t fail at anything. If you fail, you don’t know when your next opportunity is going to be.

Chloe: So much of your personal and creative evolution has come through in your more flamboyant styling and fantastical representations of masculinity on-stage.

RJ: I always like to toy with femininity and masculinity [with LSDXOXO]. I have the same approach on a daily basis, but I used to be more heavy-handed in weaving the femininity into my personal style. I would wear wigs and makeup and dresses sometimes, and people began to call me a drag queen. I wasn’t okay with that, because I’m not a drag queen. I’m a musician. It’s an exploration of self, of gender expression.

Lately, I am more interested in the balance between the two. My signature silhouette nowadays has a loose, baggy bottom, and something form-fitting and delicate on top.

“If you create this space between yourself and your audience, there’s always going to be mystery, and they’ll always want to know more. That’s kind of a power in and of itself.”

Chloe: Pop music has long disseminated fraught politics around gender and sexuality. Do you intentionally infuse a queer, BIPOC point of view into LSDXOXO to subvert these narratives? It feels as if there is a paradigm shift in how a lot of artists of color are expressing sexuality in pop music.

RJ: My experience as a gay Black man is woven into my work and pretty much everything I do. As a musician, as an artist, you kind of owe it to your fan base to be vulnerable. It makes people more invested in what you do. While I’ve not been intentionally weaving my lived experience into my work, it just happens organically—my experience feeds my work and vice versa.

Chloe: Is this why you decided to revisit Lil’ Kim’s post-feminist anthem ‘Suck My Dick’ in your track ‘SMD’?

RJ: The Lil’ Kim song was an important reference for me. I get a lot of my approach to songwriting and music-making from artists like Lil’ Kim because she’s unapologetically sexual and feminine—two things I prioritize within my work.

And this song is super nostalgic for me. I remember my mom playing this album for me from front to back when we were on car rides or cleaning the house. I would be listening and taking notes—this album was absolutely essential in shaping my musical taste and my approach to songwriting.

Chloe: On that note, most, if not all, of your songs make use of raunch and sexually explicit lyrics. What’s drawn you to these themes?

RJ: People who [had] restricted or super religious upbringings tend to rebel against their taught practices, because they can seem radical or extreme. Organized religion is not something that I easily conform to. My biggest gripe with it is that it’s so tied to colonialism—and historically speaking, that’s been very negative for the Black community, especially in America. It’s been a long-term struggle for me. That’s obviously also tied to my sexual identity.

Becoming a musician, I’ve tried to break away from my religious upbringing and use my music to rebel [against it]. It’s a way of reclaiming bits of my lived experience and identity that I was taught to be ashamed of. I guess that’s why I’m so explicit and unapologetic.

Chloe: I’m curious where you see the boundary between smut and sensuality. Does the provocation have purpose?

RJ: I’ve always used smut and vulgarity in my work. Now, I’m trying to find a way to approach a wider audience of people who may be younger or older or from different backgrounds. I’m trying to find a balance between using sensuality in my work and not being too heavy-handed or too vulgar [with it]. I’ve had my Instagram account deactivated so many times, because eroticism is not widely accepted.

“As a musician, as an artist, you kind of owe it to your fan base to be vulnerable.”

Chloe: My understanding is that you’ve made a concerted effort to learn pop song structures and superimpose them onto dance music. What is the impetus behind that?

RJ: I’ve always been a pop music nerd. I think the first pop star who I was just obsessed with was Britney Spears. I was like, ‘Mom, I don’t know how you didn’t know I was gay when I was asking for Britney Spears Live from Las Vegas DVDs when I was eight years old.’ I’ve always wanted my work to eventually be in the scope of pop music. And obviously, that would be on my own terms. I wouldn’t want that to affect how I make my music, because I still want my music to be me. But the structure of pop music interests me, because an earworm is really powerful, and not everyone knows how to [make] that.

Chloe: What do you make of pop’s resurgence over the last few years? Does its appeal with a dance music audience say anything about the current cultural zeitgeist?

RJ: Pop personality nowadays has been turned on its head, just because the chance of becoming successful—if you are good at what you do—is a lot higher. It used to be based on geography and scratching the right back. But artists are much more autonomous nowadays, because we have the power of self-promotion. It’s has created a really interesting musical landscape, because a lot of the artists who are popular right now are young, and didn’t have to sign away their life to make music. Popular music has become a lot more fun because of that. There are now a lot of artists who don’t feel that they have to comply with the standards of pop music-making and mainstream sound. It’s exciting to hear artists say, Well, okay, I want to actually release a 150-BPM club music record for the radio.

Chloe: I also find it interesting that you have chosen to work with other producers on your album, because that’s more of a standard for pop music than underground music.

RJ: I want my album to have a more grand soundscape. I wanted to go to artists who know how to do that. It’s nice to have another ear and another brain in the process of making music; if you’re producing your own music—as well as writing it and singing it and performing it—it’s very lonely.

Chloe: You’re launching a label in tandem with your EP. What can you disclose about it?

RJ: The label is very much bare-bones right now. In Germany, it takes forever to register businesses, so it’s just a long and tedious process, even though we’ve begun officially announcing and starting the imprint and signing artists.

It’s important to me that I own all the masters for my music. This is something that I want for the artists that I sign to my label, too. Historically speaking, the music industry can be like slavery, especially for POC or queer musicians. The contracting can be relentless, and that’s just not my process. I don’t want to start my own record label just to stifle what can happen with the music.

Make-up Hugo Villard at Calliste. Photo Assistant Frederic Tröhler. Stylist Assistant Joss Rowe. Production COMPANY. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan.