For Document’s Spring/Summer 2023 issue, Jesse Doris looks back on the transgressive queer digest, and the subculture it willed into existence

“‘Queercore’ fanzines aren’t supposed to be catalogued and canonized and analysed to death, for Chrissake. They’re supposed to be disposable. That’s the whole point. Throw your fanzines away right now. Go ahead. Photocopied material doesn’t last forever, you know. It fades… Dilettantes and librarians… collect and copy and catalogue, and ultimately take credit for, ideas which should be left to those who live them.”

—Bruce LaBruce, The Reluctant Pornographer

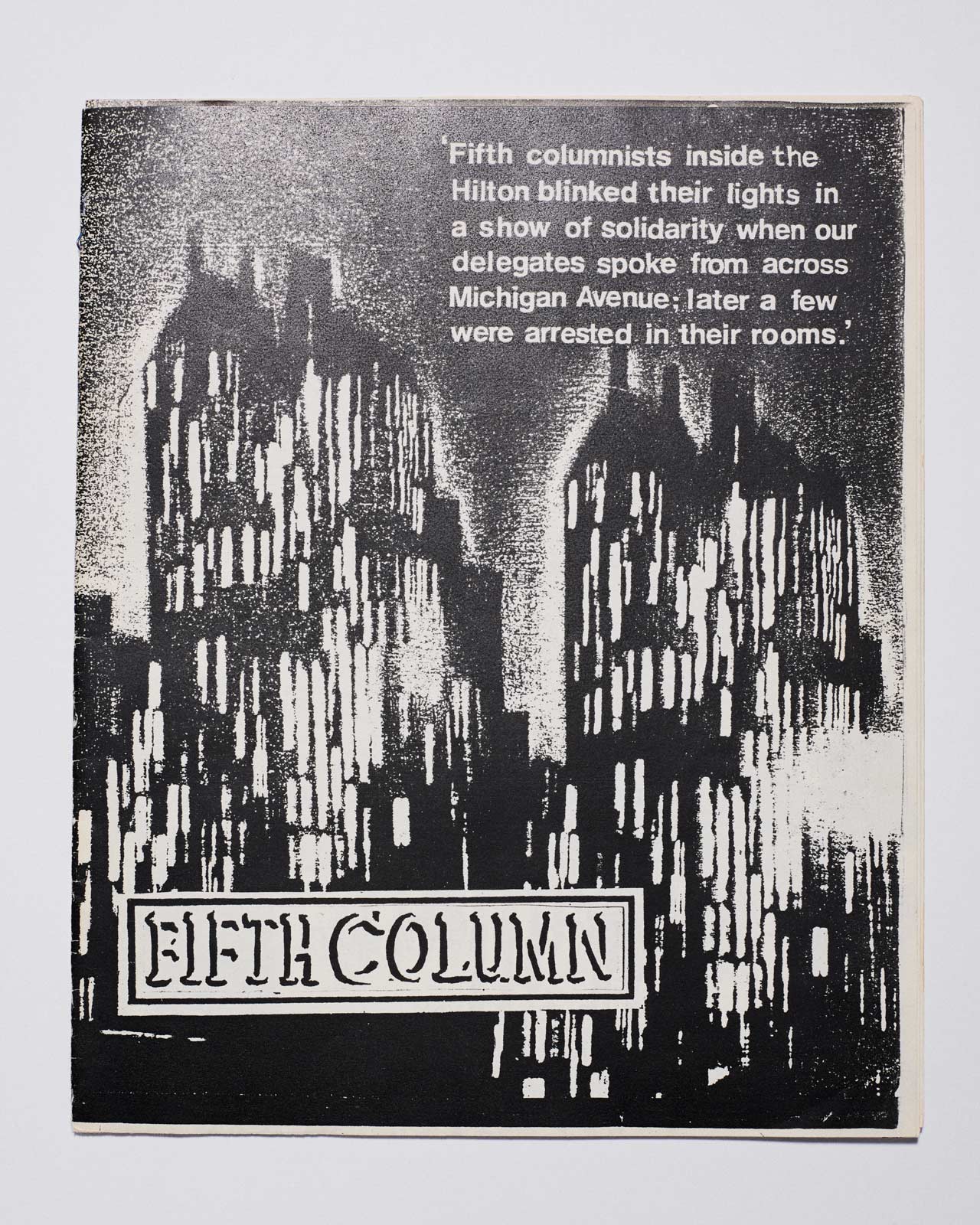

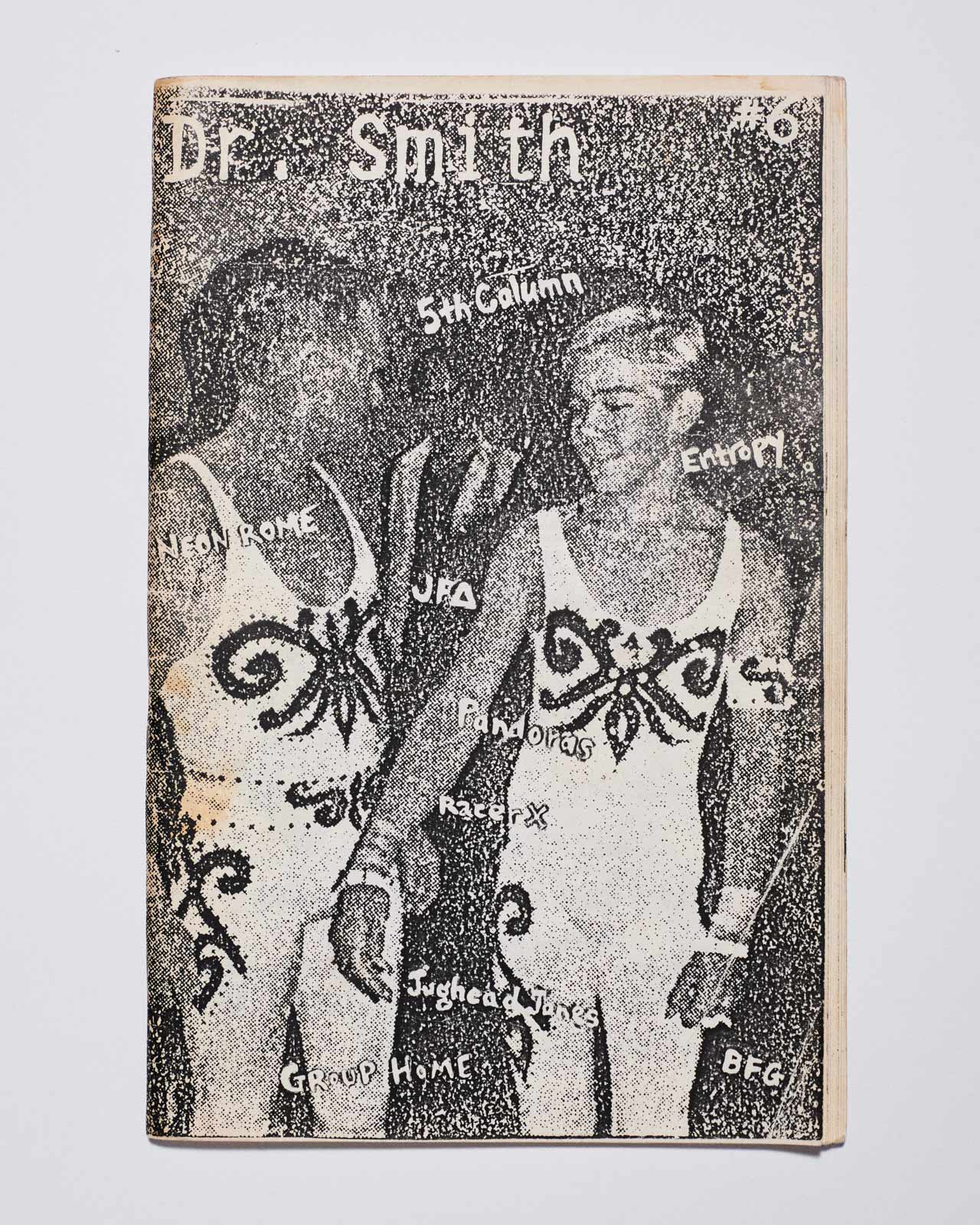

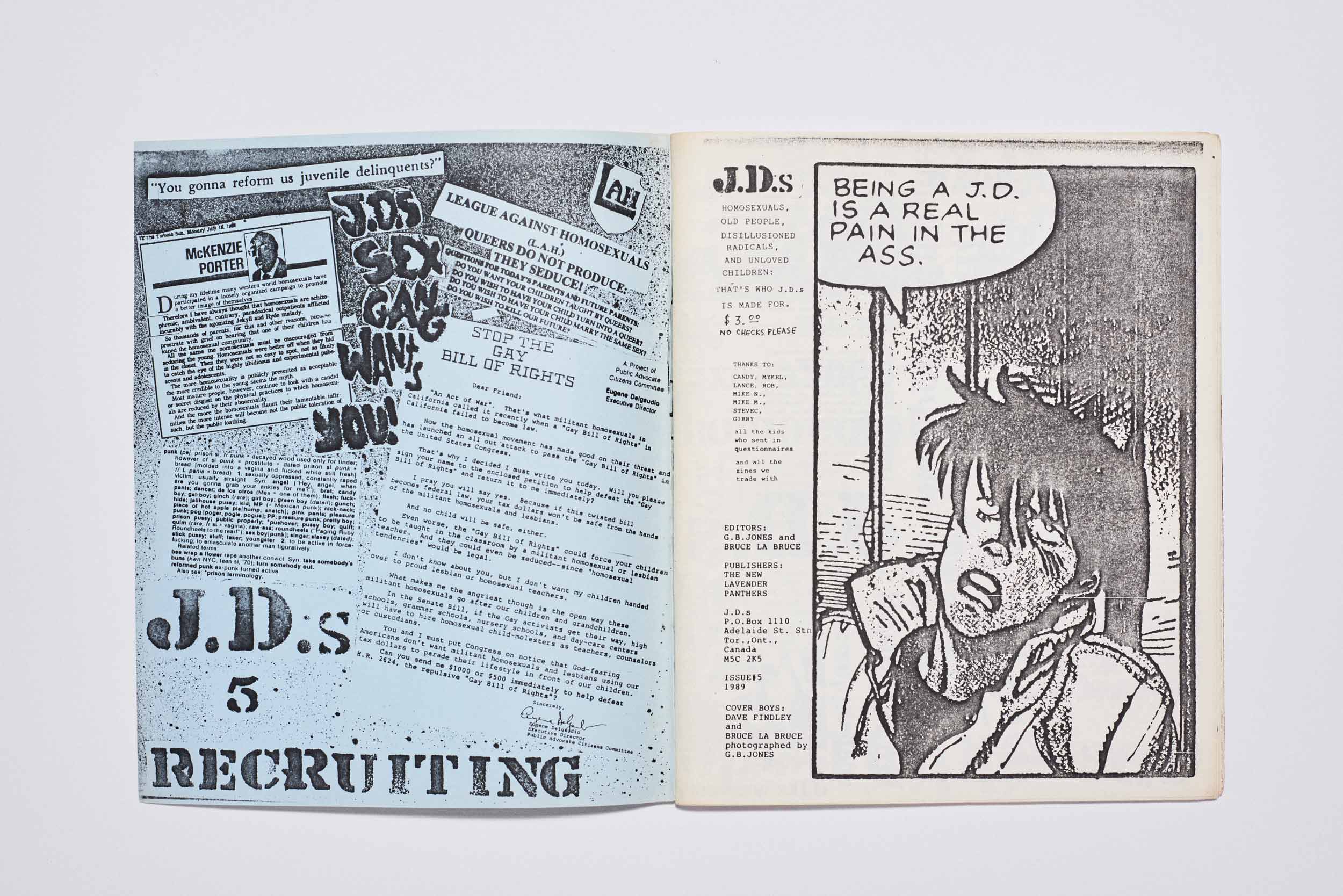

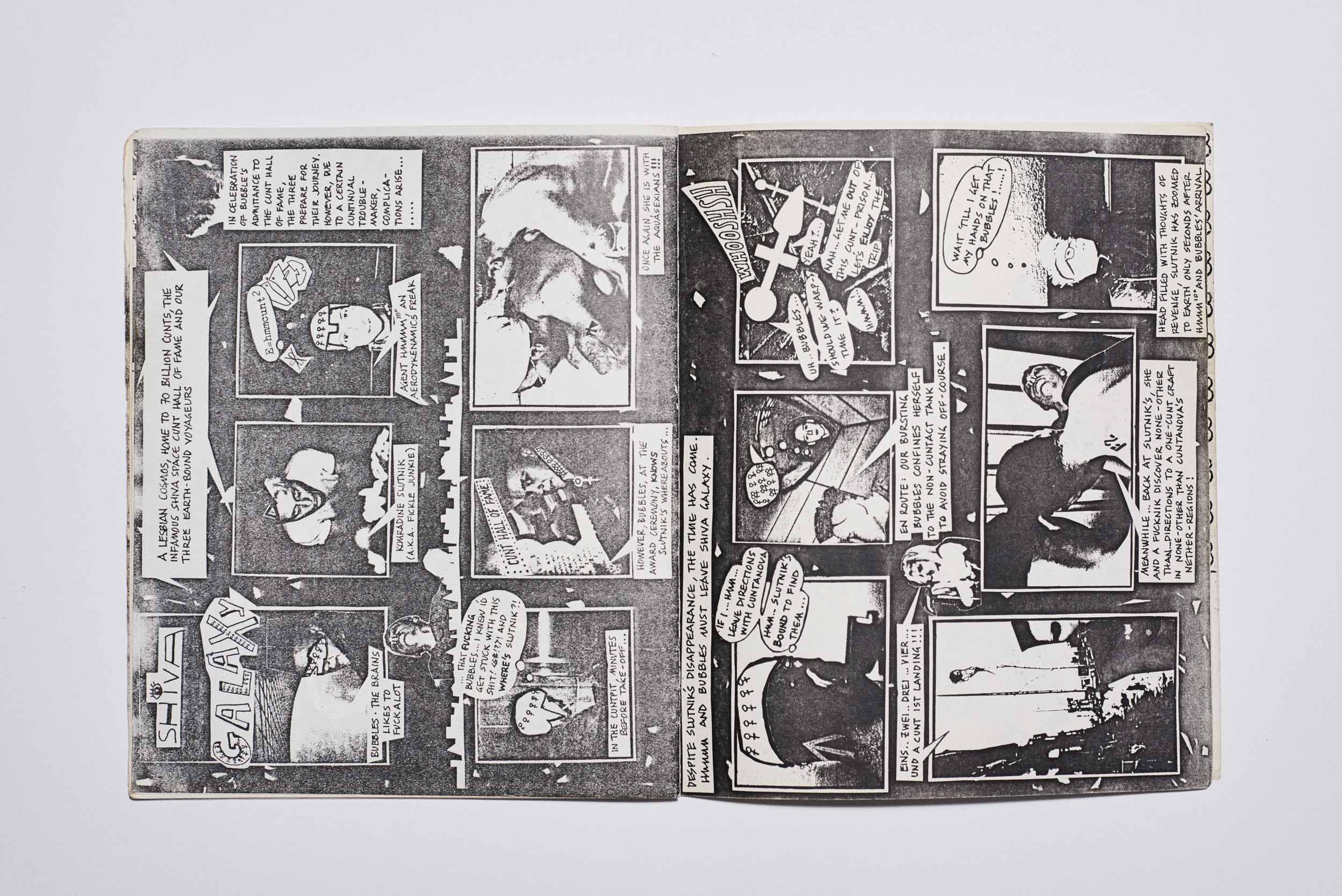

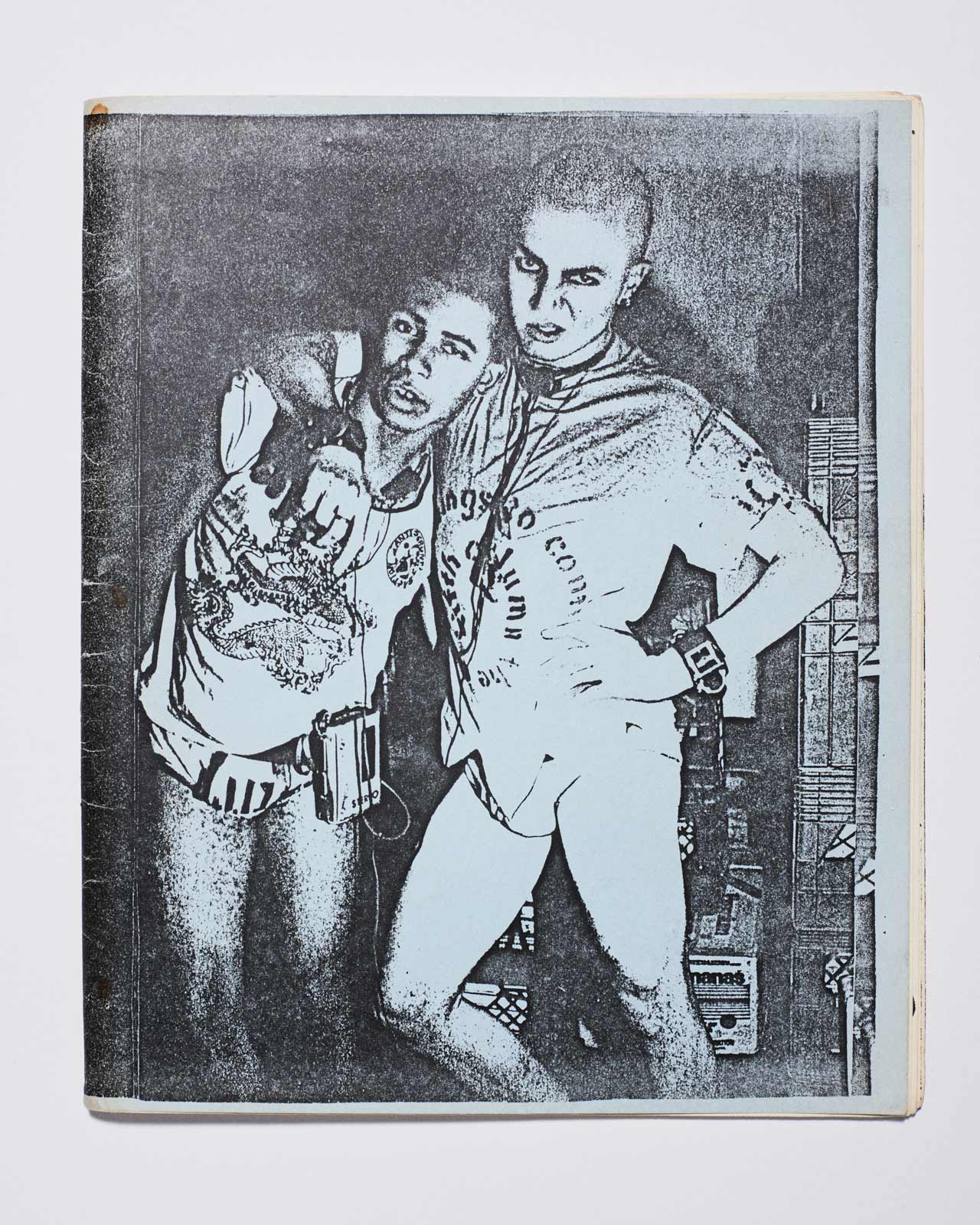

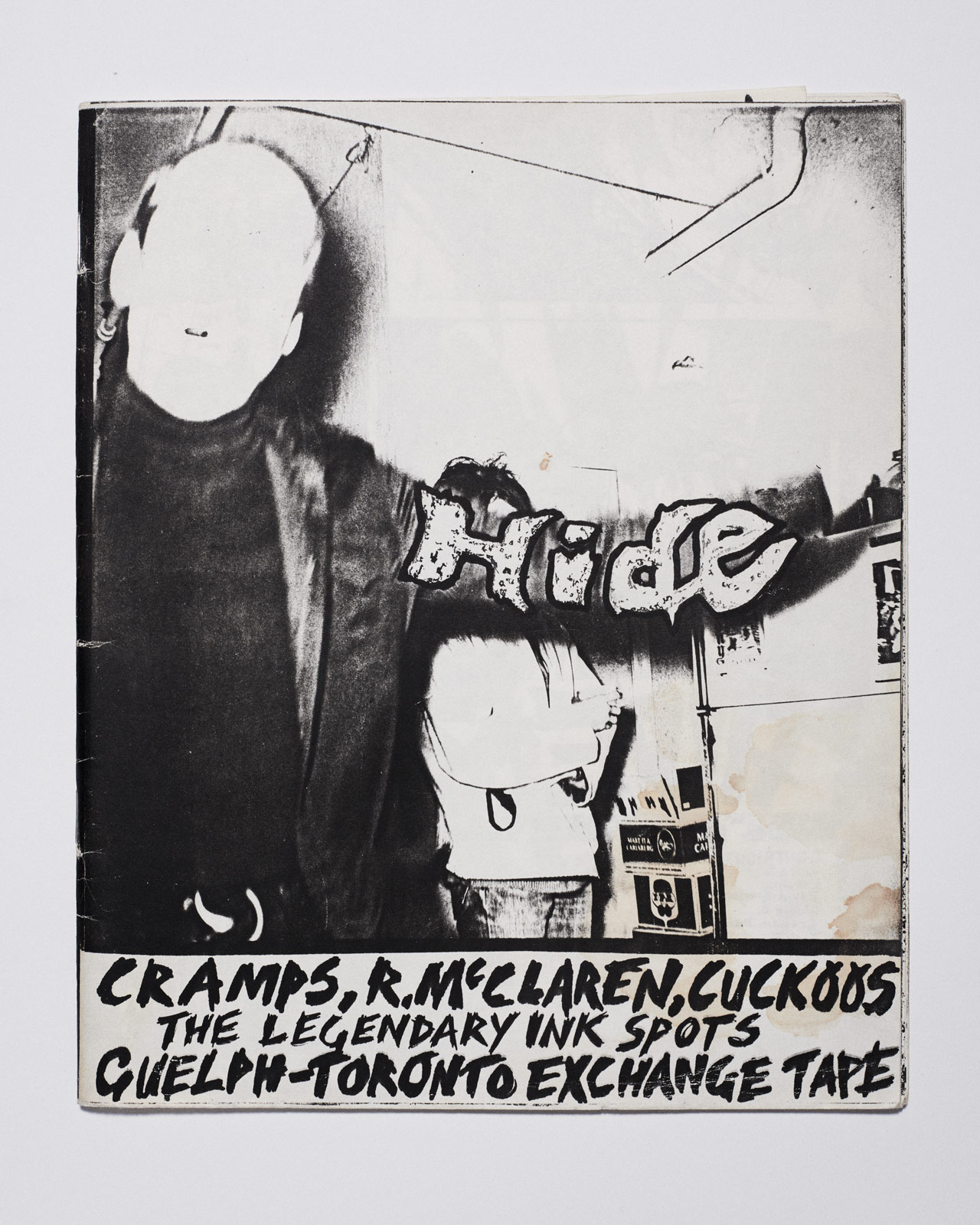

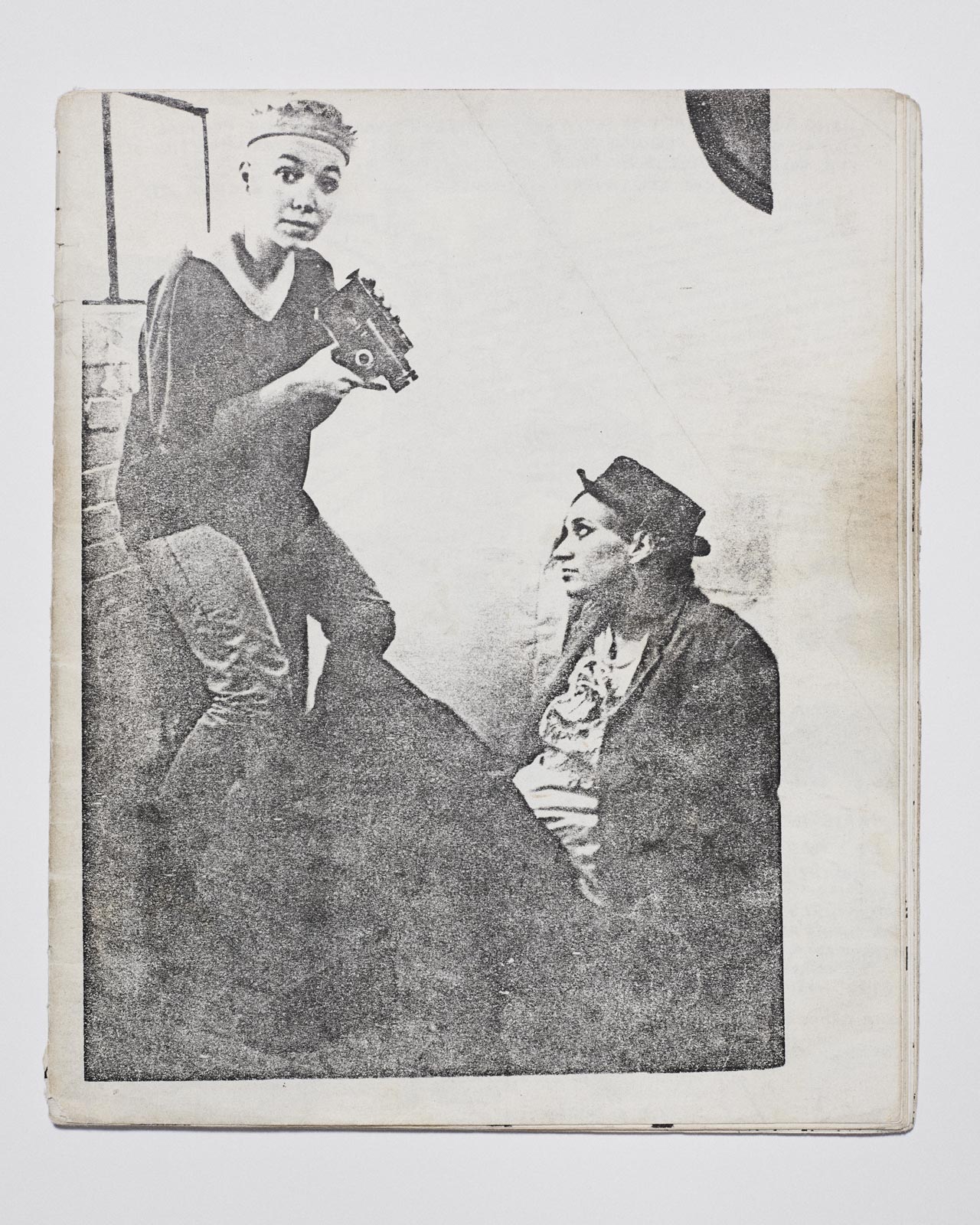

Once upon a time in Toronto, there was a restaurant specializing in avant-garde desserts and confrontational service. Two servers met on the night shift. One of them—who had recently reinvented himself as Bruce LaBruce—looked like a Liquid Sky extra and was studying Marxist-feminist film theory. The other, G.B. Jones, was in a cool punk band called Fifth Column and was known around town for the zine she edited alongside Caroline Azar, called Hide, which layered local scene coverage with xeroxes of chain links and found photography. It mixed the demimondes of zine and cassette culture, releasing paper copies with compilation tapes of underground music. The pair hit it off: LaBruce became Fifth Column’s go-go boy and moved into a squat next to the band’s rehearsal space. Soon, he and Jones were making a zine of their own. In eight gorgeous and wicked issues, J.D.s would invent a scene, turn it into a movement, and burn it all down.

“In the beginning was the word.

That’s how somebody tried to explain it once.

Until something is named, it doesn’t exist.”

—Samuel R. Delany, Babel-17

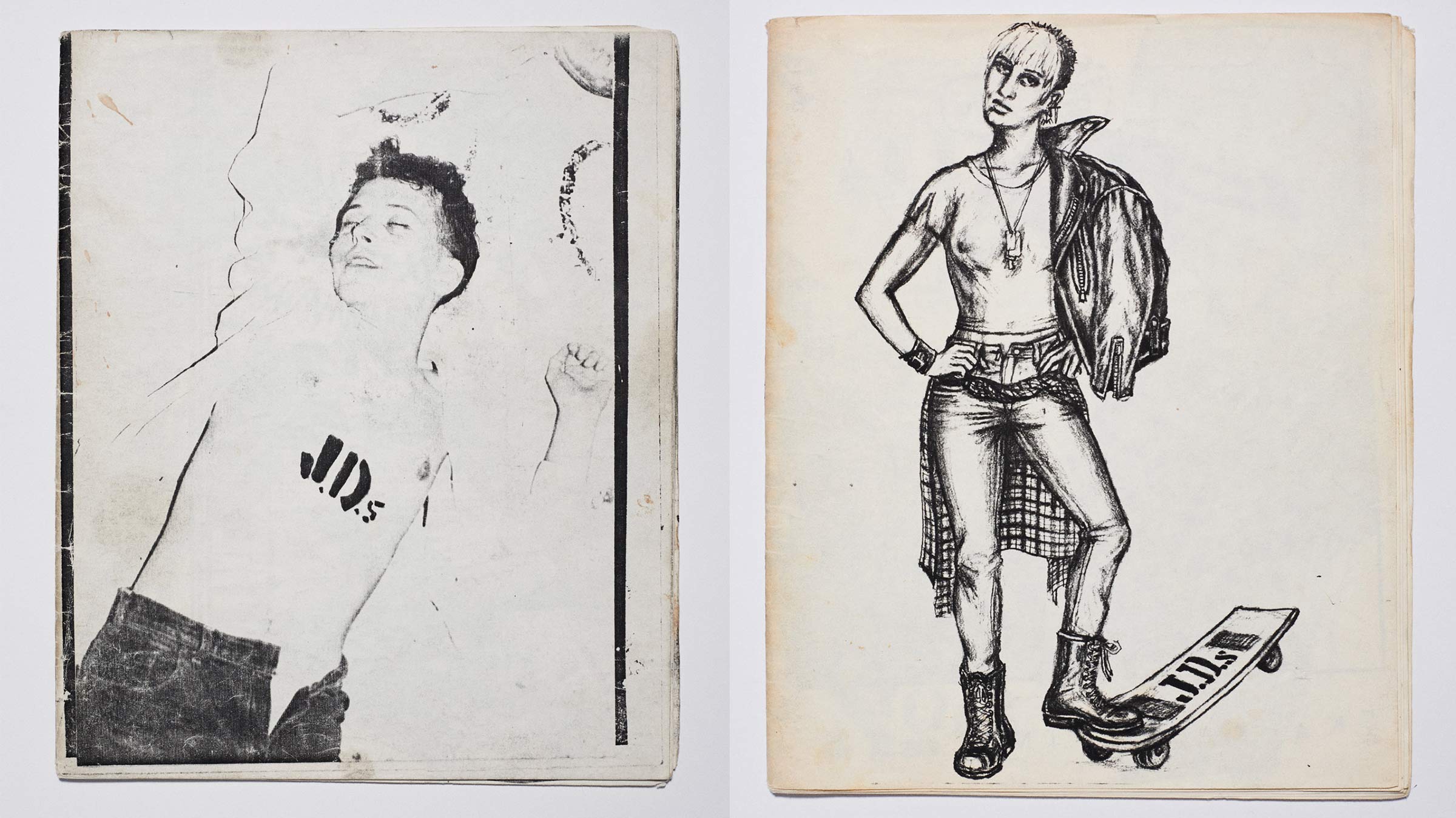

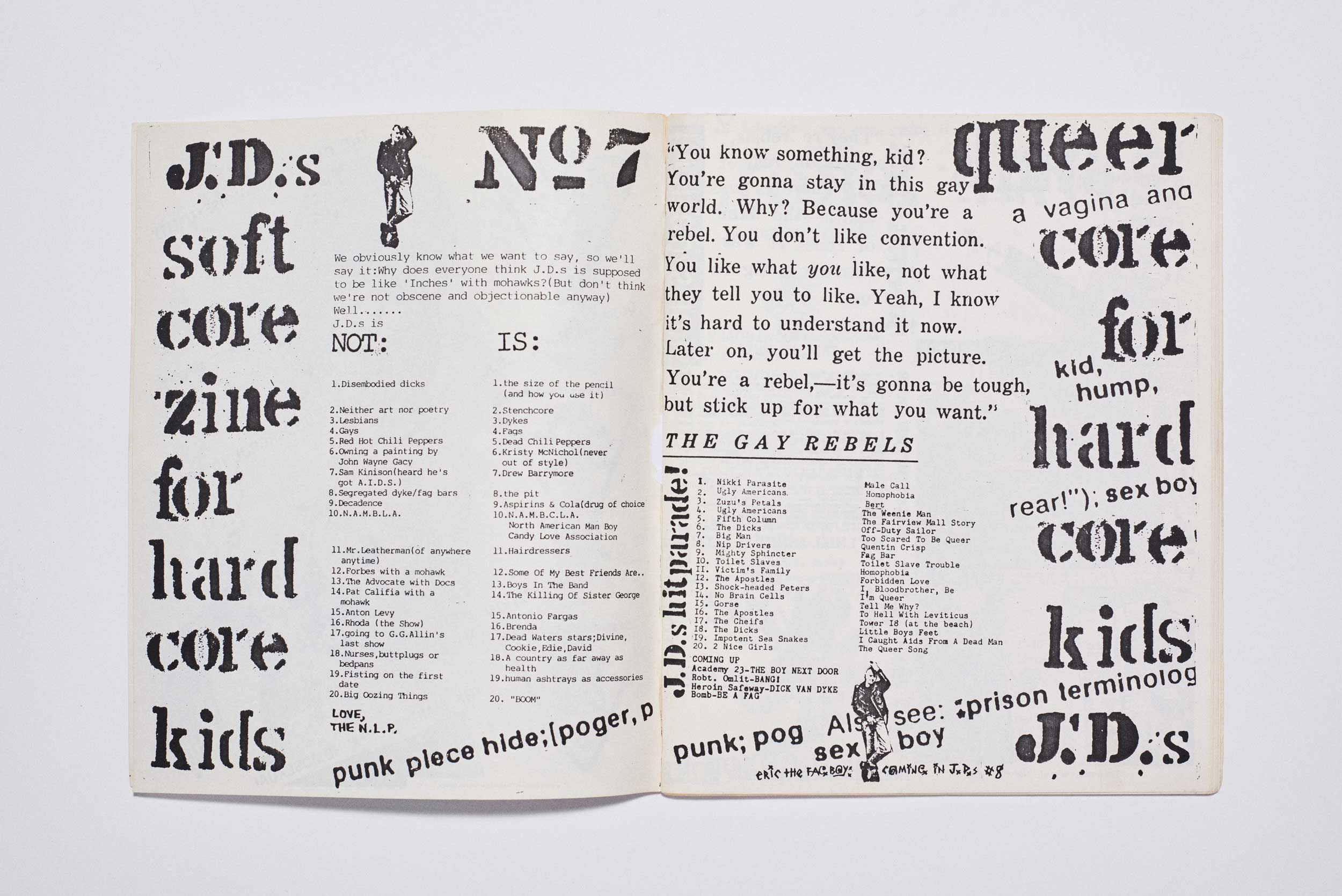

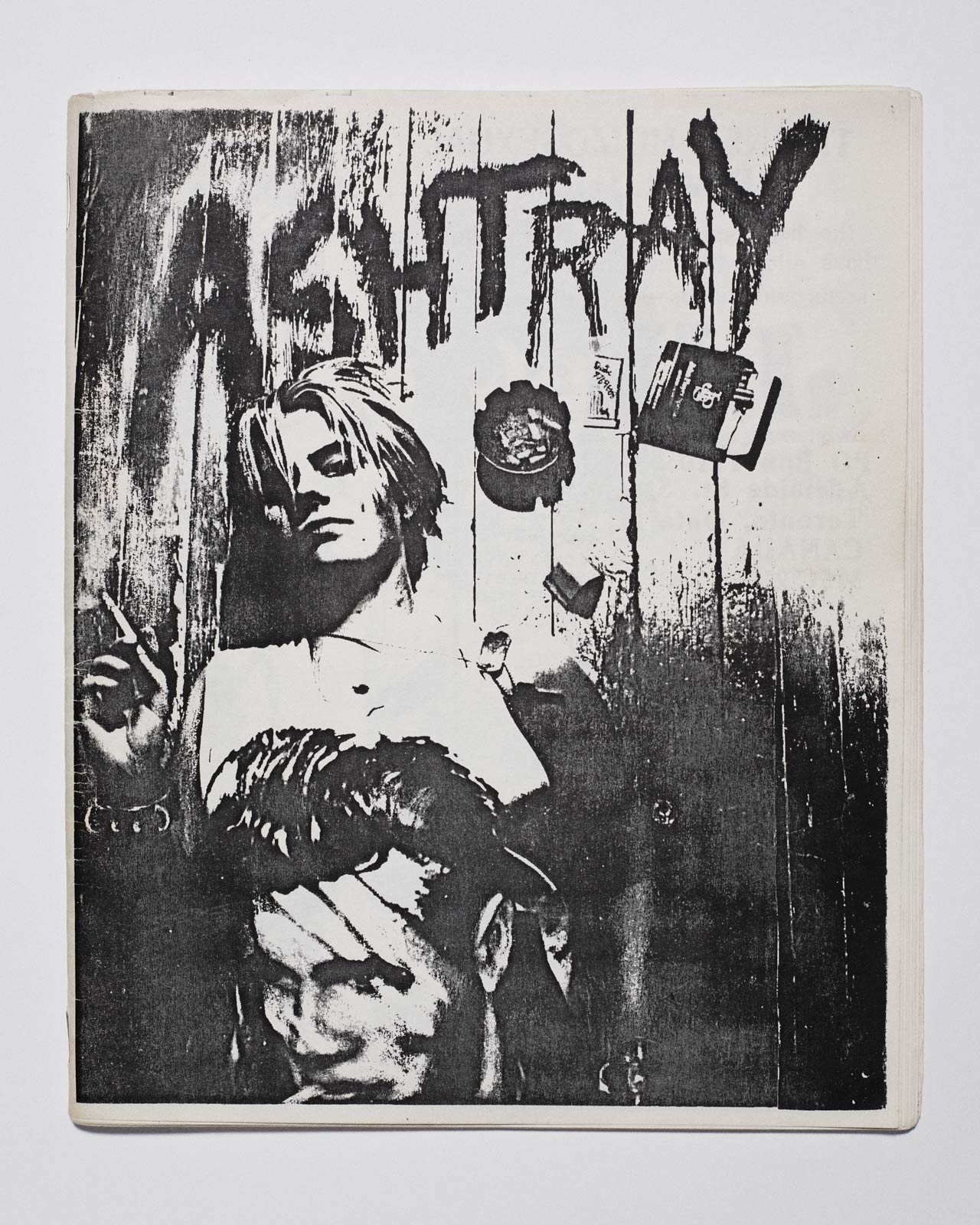

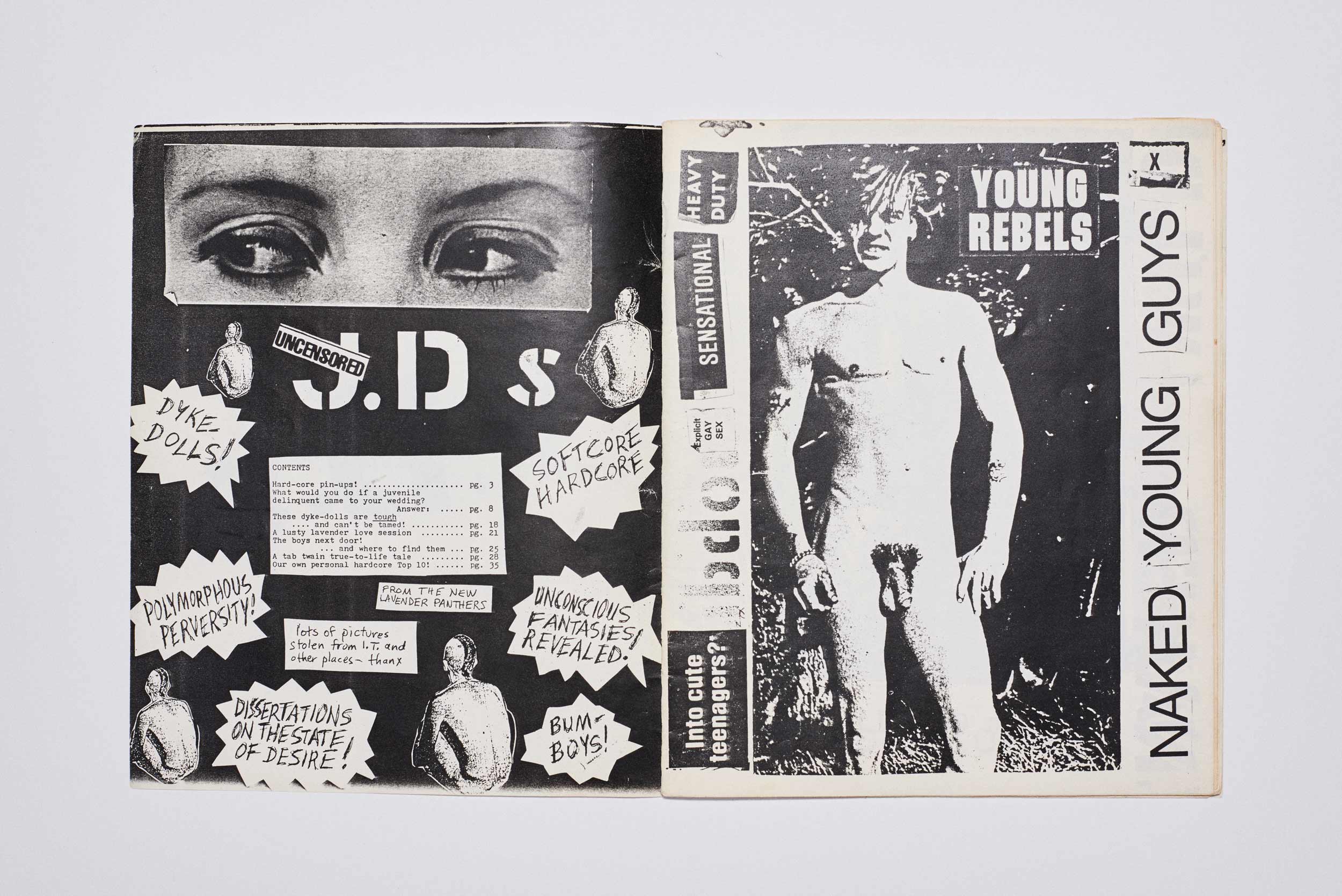

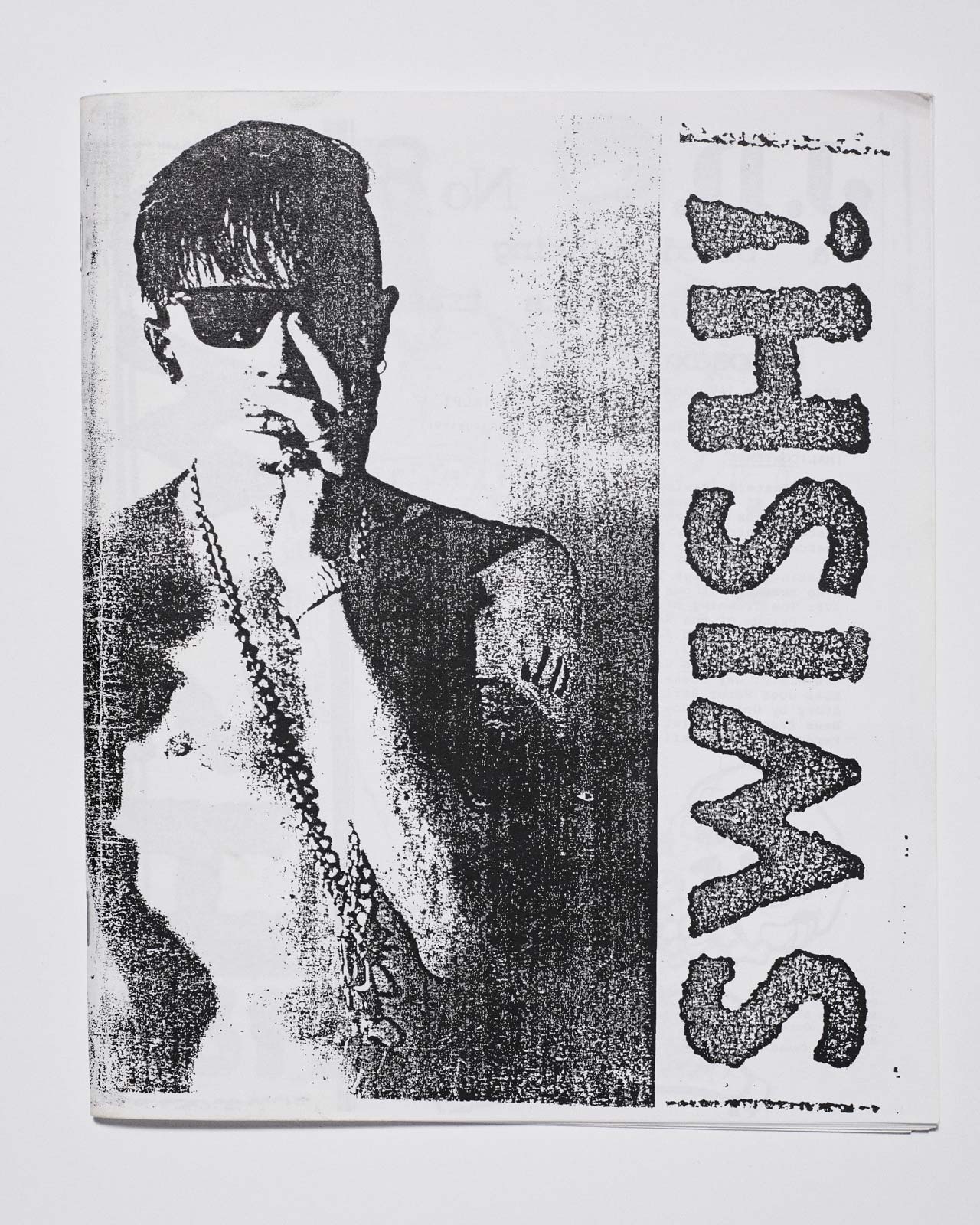

It’s all there in 1985’s first issue: The cover looks like a boot stamped its title on a crumpled piece of paper. Pry it open, and 30-odd pages of fun unfold. There are xeroxed photos of beefy punk guys horsing around—or showing off their horse cocks. In Jones’s bravura illustrations, butch dykes reclaim Tom of Finland’s Valhalla for their own hijinks. A “J.D.s Top Ten Homocore” names the hits of a scene LaBruce and Jones weren’t really sure existed, corralled in their corner of Ontario. But they knew bands like Aryan Disgrace were making bawdy punk blasts like “Faggot in the Family,” because they heard them. That meant they weren’t alone. And isn’t that what a scene is, anyway? The “Top Ten” list (soon swelling to “Top Twenty”) became J.D.s’s signature, at once its proof of concept and recruiting tool. Often, a photo of a muscly mohawked dude sat next to the list, as if listening to the songs. As if he could be you. As if he could be yours.

“Do you see yourself / In the magazine… /

Did you do it for fame / Did you do it in a fit /

Did you do it before / You read about it?”

—X-Ray Spex, “Identity”

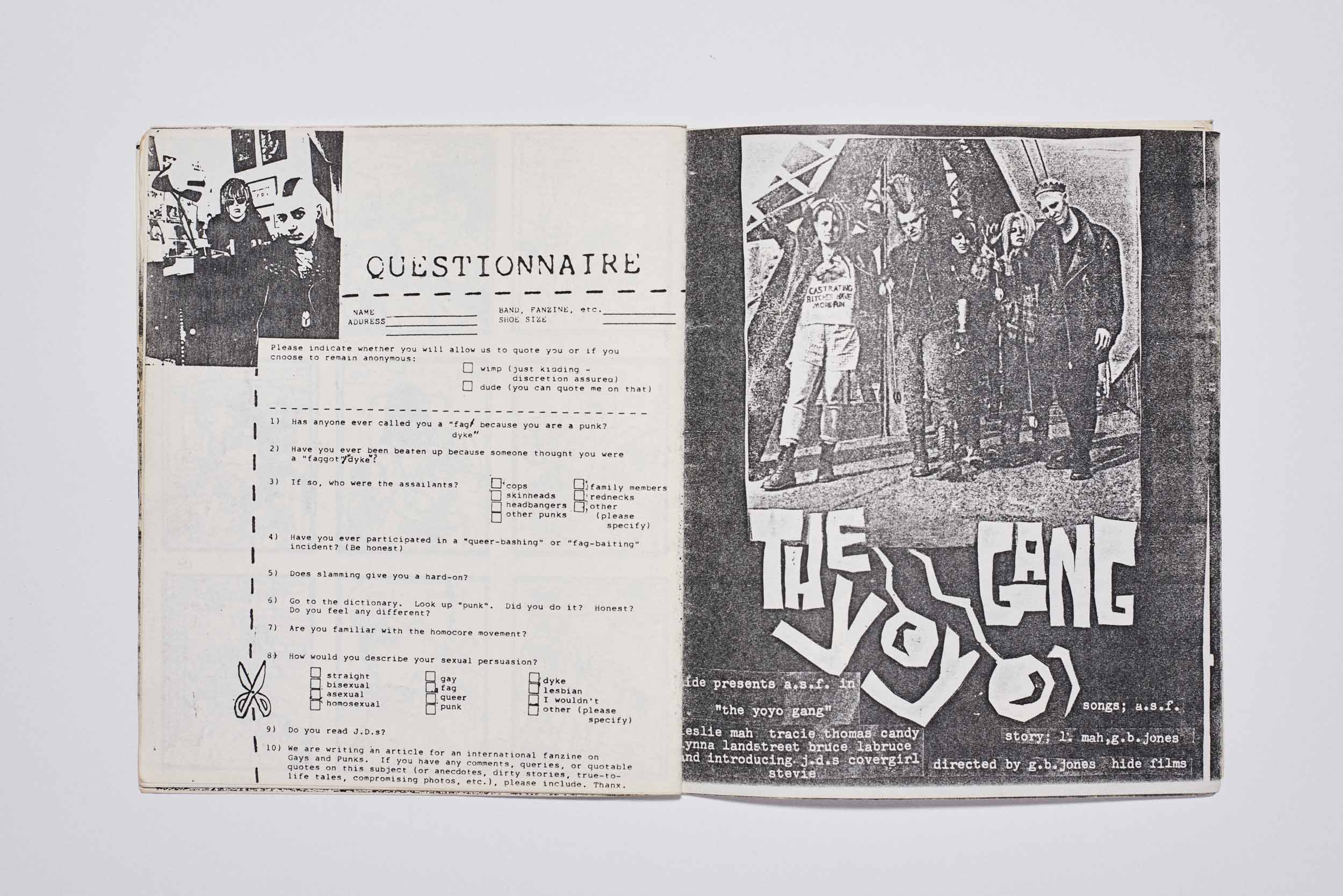

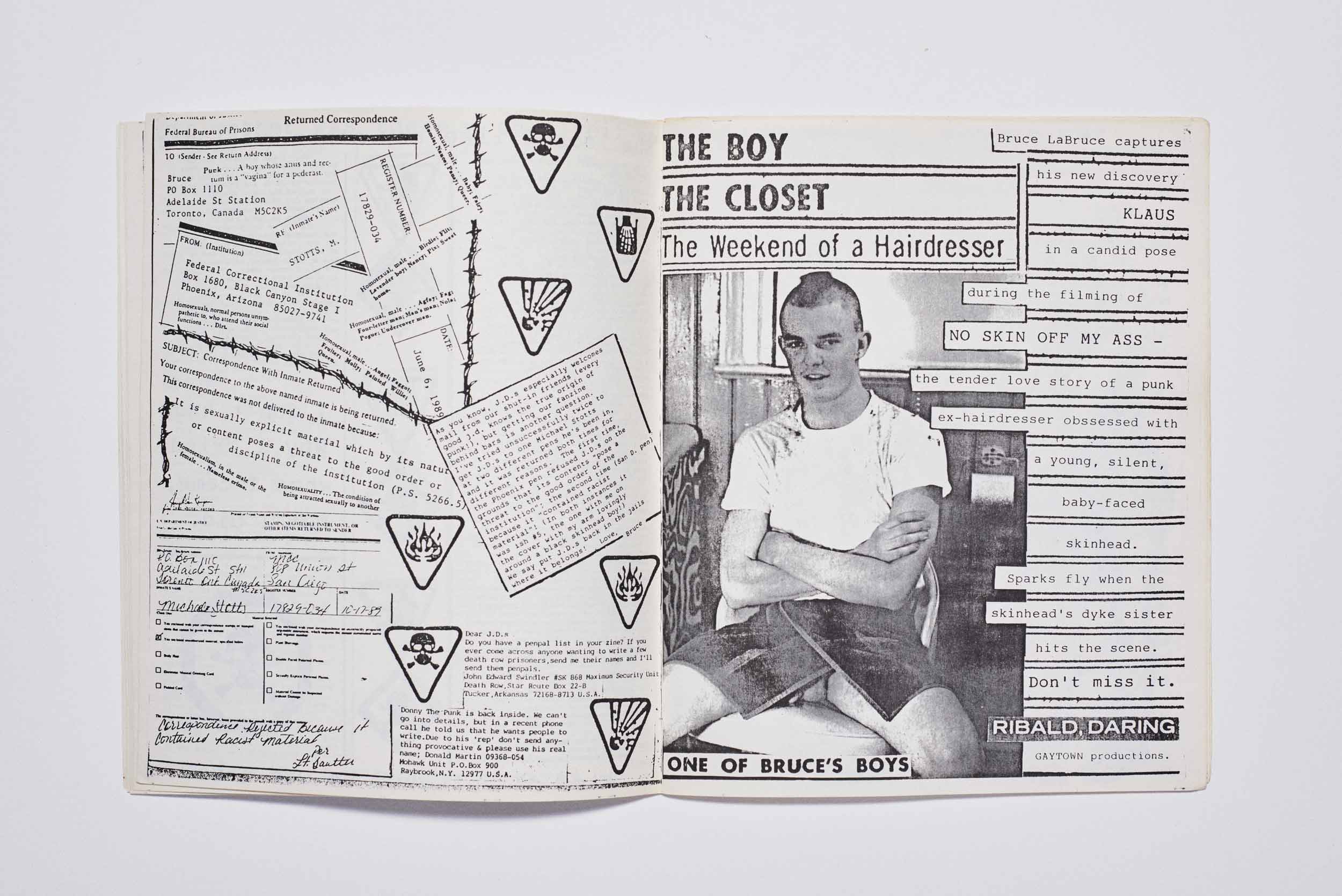

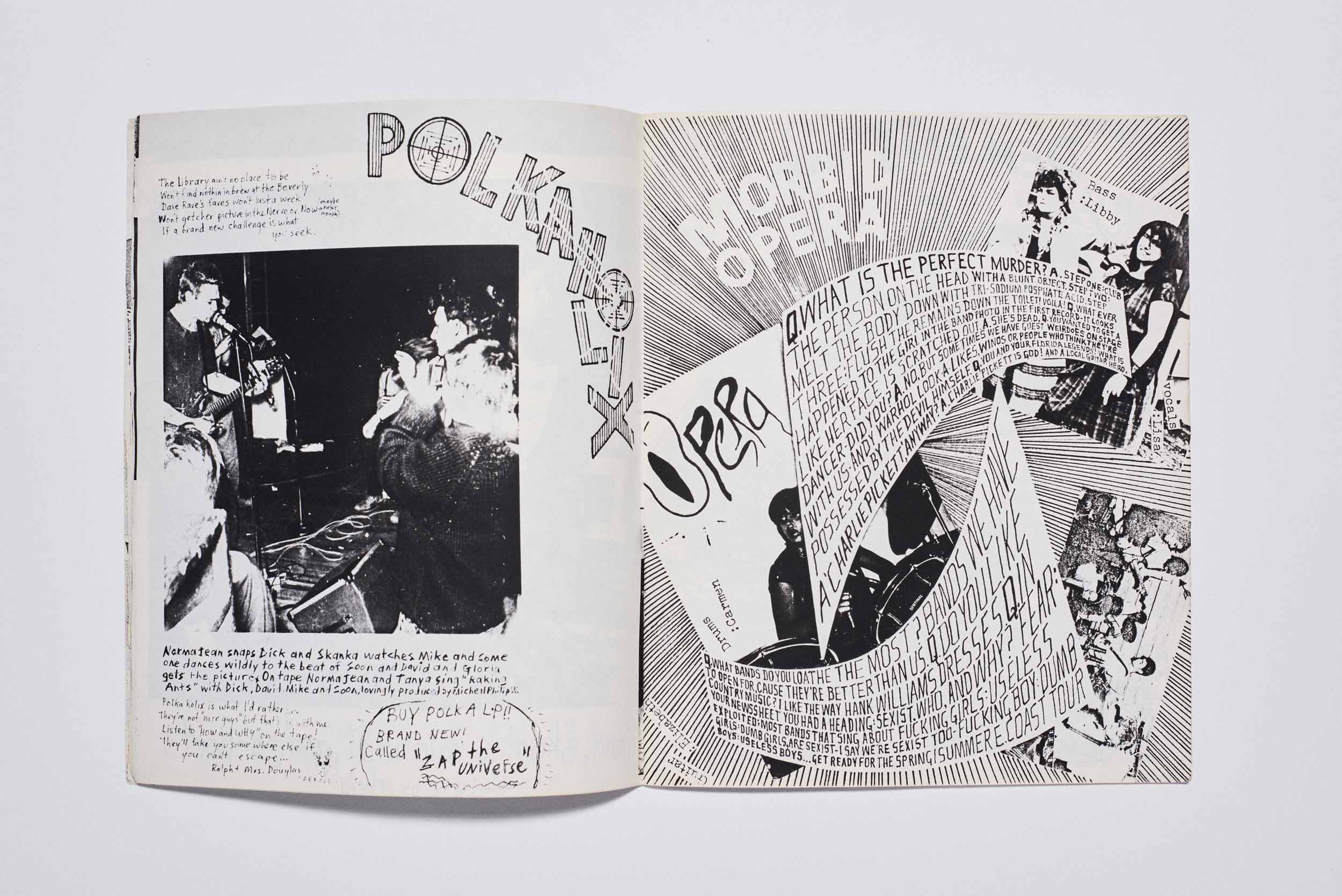

J.D.s willed a subculture into existence by collecting its ephemera—and creating the ephemera, too. By its fourth issue, Jones and LaBruce were running ads for their Super 8 movies, and for the art and porn their friends and strangers were making. They bragged about getting banned from local bookstores and tucked questionnaires between the zines’ pages, telling readers (in a queer admixture of self-help and Fluxus), “Go to the dictionary. Look up ‘punk.’ Did you do it? Honest? Do you feel any different?” The photocopied collages were getting knottier, loosening the bondage of the old punk cut-and-paste, and instead threading together strategies of cut-up, montage, and concrete poetry. Not to worry, the stories of grateful transformation into human urinals for skinheads still popped up, as did early publications of future heroes like Dennis Cooper. By issue seven, enthusiasm was flagging: A cartoon titled “Stupid Fags Worship the Oppressor!” included an illustration of one man licking a cop’s boots above another licking a Nazi’s Doc Martens—J.D.s’s fundamental fashion accessory—in a spit take at gay culture’s fetishization of butch authority figures. Below, a chunk of text prodded further, questioning gay culture as a Thing itself: “If someone were to put out a ‘straight’ version of J.D.s, they would be nailed to a cross in a minute. I’m not putting down gays, women, or anyone. I’m just saying our sexual values may be a little screwed.”

“To achieve harmony in bad taste is

the height of elegance.”

—Jean Genet, The Thief’s Journal

LaBruce and Jones spent six years making eight issues of J.D.s, each more popular than the last and increasingly populated with LaBruce’s self-promotion. By 1991’s final installation, he was the honest-to-god filmmaker he’d always threatened to be, via the fabulous full-length No Skin Off My Ass, in which he starred as a Lonely Hairdresser buzzing and fucking punks. Jones had astonishing films under her belt, too—BDSM-fueled, feminist, picaresque Super 8 shorts The Troublemakers (1990) and The Yo-Yo Gang (1992). The pair had taken their act on the road, showing their work and building alliances with the genius Los Angeles performance artist Vaginal Creme Davis, San Francisco Homocore zine publisher Tom Jennings, and proto-riot grrrl bands Tribe 8 and Team Dresch. Along the way, they fell out of sync. Whispers on the wind indicate that she said some ungenerous shit about him; he wrote some awful things about her in the music magazine Exclaim! Still, over the years, J.D.s’s reputation was engorged.

“In the future, once the history of J.D.s has been wiped clean from Toronto, someone will find this old zine in an old bookstore somewhere—although they’re probably trying to wipe out the bookstores; they’ll go to the Archives and find it there, and think, Wow, look what used to happen here! And hopefully be inspired.”

—G.B. Jones, Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution

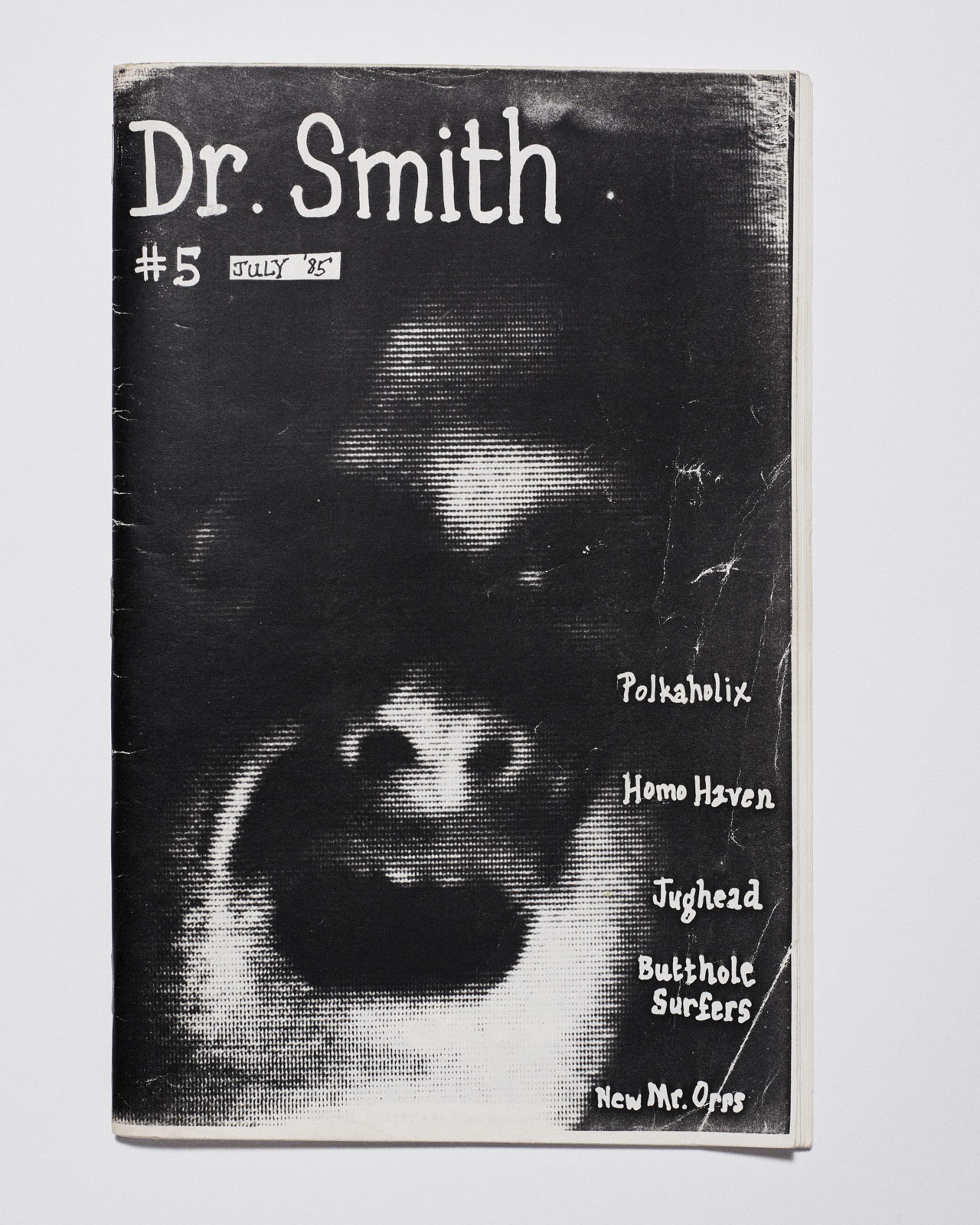

Today, it feels like a hot piece of gristle. A connective tissue for a certain kind of reader. At one end, it fits into the thick stack of ’50s Hollywood fanzines, the fly-on-the-bathroom-stall epistolary filth digest Straight to Hell, art publications like fellow Torontonian queer art collective General Idea’s FILE, and punk zines like Search & Destroy. At the other end, it belongs with quick-on-the-heels follow-ups like Holy Titclamps, the great wave of riot grrrl zines like Girl Germs and Gunk, and 2001’s art-fag renaissance bible Butt. Each of these zines makes its own kind of fame through its own kind of fables. Double fabulists LaBruce and Jones seemed to delight in tossing J.D.s into the trash. Which is a shame. But then, trash is what they always delighted in. Go rummage around and make something yourself.