The filmmaker and Saint Laurent Productions’s artistic director reflect on 'Strange Way of Life,' and giving new impetus to its decade-old script

Lydia Tár’s deliciously sleek and commanding wardrobe. The candy-colored ’50s frocks of Don’t Worry Darling. Tilda Swinton in a scarlet Balenciaga crinoline dress in Pedro Almodóvar’s short The Human Voice. Three snapshots from modern cinema. Fashion has always loved movies. And movies have always loved fashion. Trying to separate one from the other would be as cruel and antithetical to nature as severing children from their daemons in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face is nothing without Givenchy. Would Givenchy be Givenchy without Hepburn?

There’s an exhilarating kind of logic in having a house like Saint Laurent launch its own film production arm. Tom Ford proved that designers could direct movies. Saint Laurent’s creative director, Anthony Vaccarello, is taking things a step further, turning the venerated fashion brand into a movie production house, with projects helmed by some of cinema’s greatest auteurs including Paolo Sorrentino, David Cronenberg, Abel Ferrara, Wong Kar-wai, Jim Jarmusch, and Gaspar Noé.

First, though, is a collaboration with Almodóvar, the godfather of Spain’s La Movida, the raucous movement that brought sex and punk to the country’s moribund film and music scene after the death of its Nationalist dictator Francisco Franco. Strange Way of Life, a queer Western in which Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal duel for one another’s love, is only the second film Almodóvar has directed in English—The Human Voice was the first. That film was based on Jean Cocteau’s 1930 play, something of a lodestone for Almodóvar, who turned to it as inspiration for his breakout hit, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

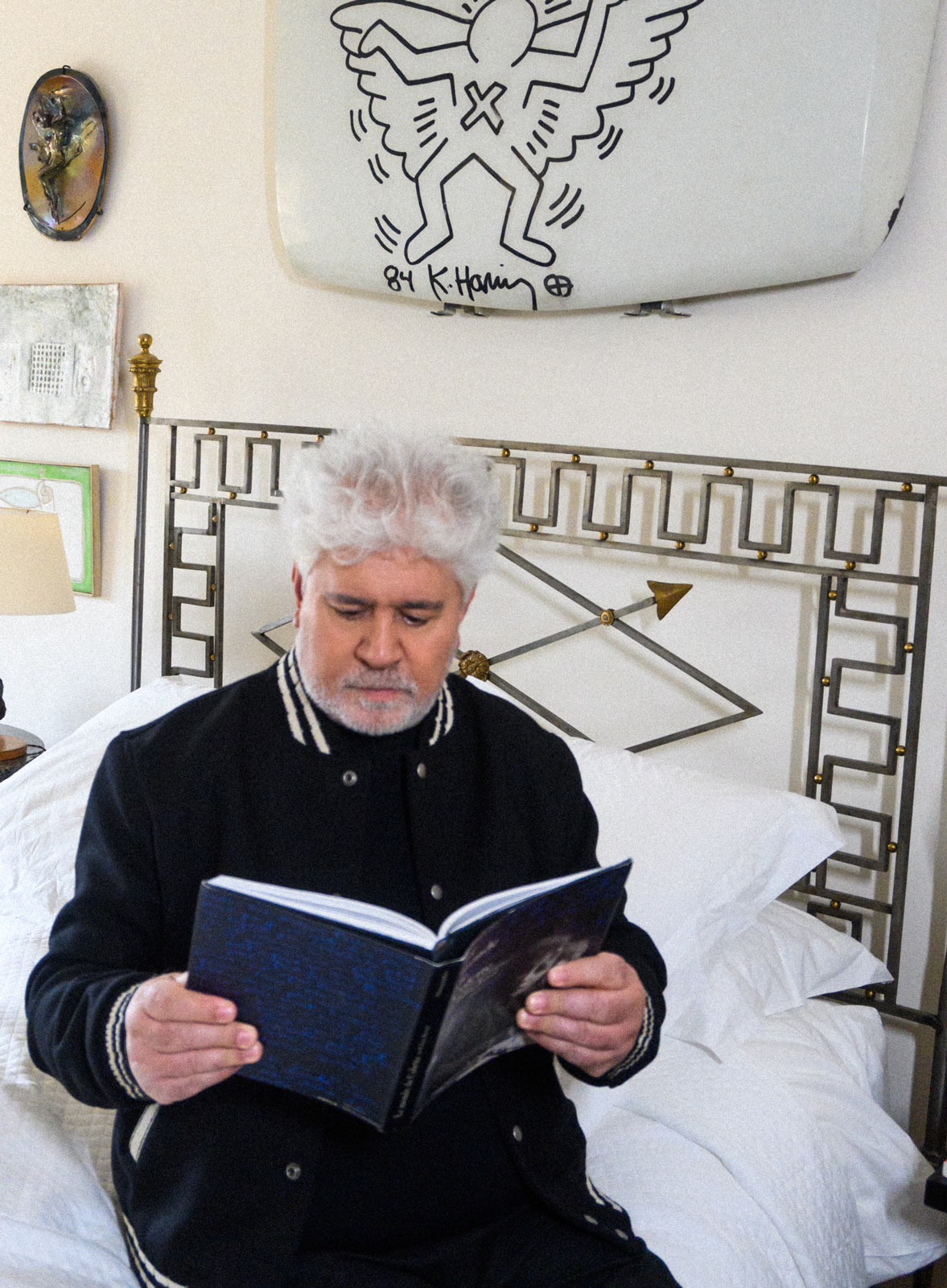

Like The Human Voice, the new movie runs only 30 minutes, and is developed from a bedroom scene Almodóvar had written and filed away a decade prior. His meeting with Vaccarello gave the script new impetus, and the filmmaker developed it into a full treatment. He has described Strange Way of Life as his answer to Brokeback Mountain, the 2005 Oscar-winning cowboy romance directed by Ang Lee. What if Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar had stayed together? Now, we get to find out. Pascal has described it as “absolutely intoxicating, dangerous, hilarious, heartbreaking.”

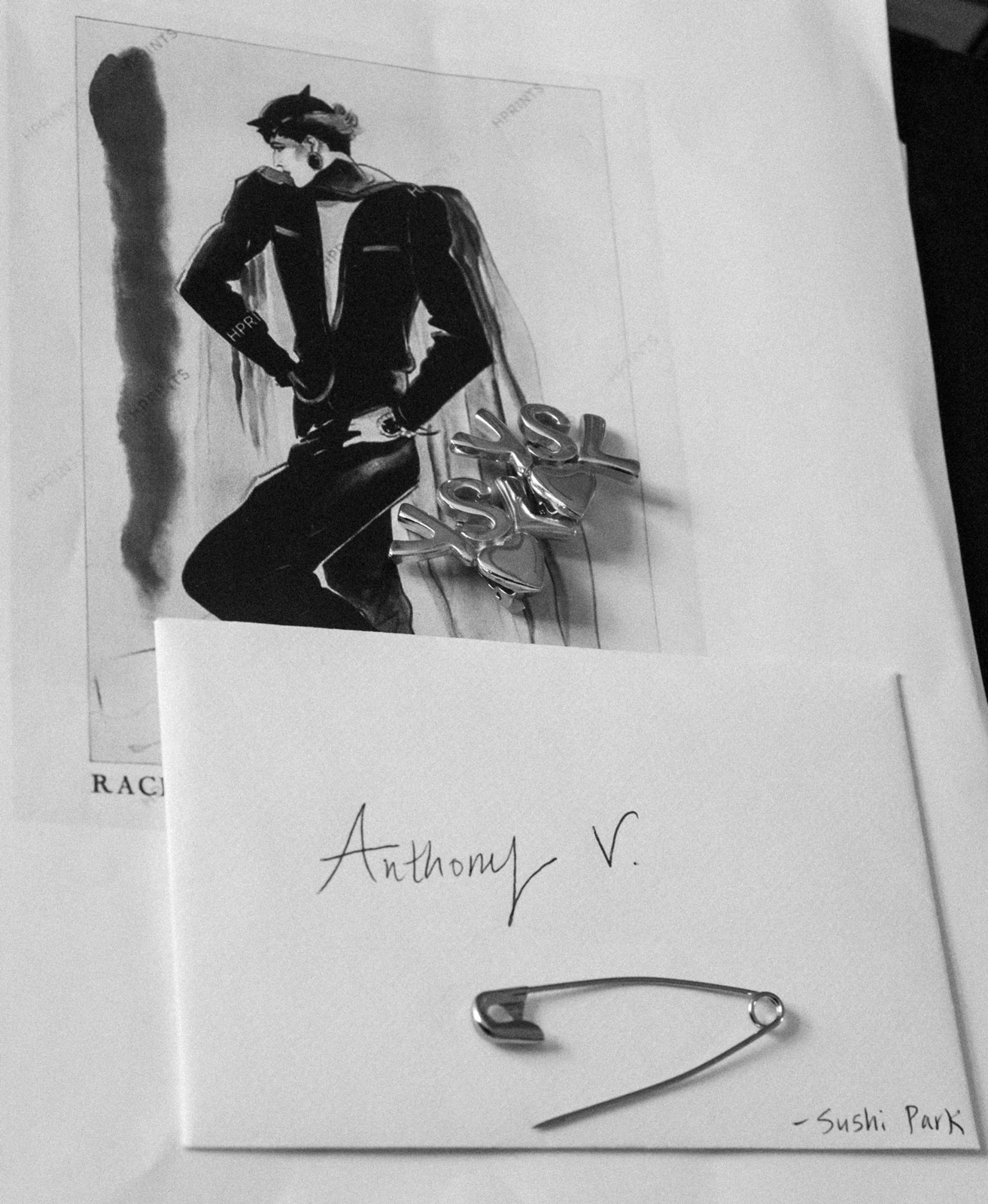

For Vaccarello, who is also the costume designer for Strange Way of Life, collaborating with Almodóvar feels like a natural extension of a role he’s been carving since joining the brand—a patron of artists. His SELF series includes a brooding romance film from writer Bret Easton Ellis, starring Hopper Penn (son of Sean); an exhibition of photographs by performance artist Vanessa Beecroft; and a dream-like film and screen installation in Shanghai directed by Wing Shya and curated by Wong Kar-wai. With his own collections, he is perhaps the most cinematic of designers. “When I think of doing the collection, I always think of that guy or that woman in a film,” he has said. “It’s kind of a fantasy I need to have to start the collection.”

Here, the two men swap observations on their first encounter, the symbiotic relationship between film and fashion, and why Men on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown would be a movie no one needs to see.

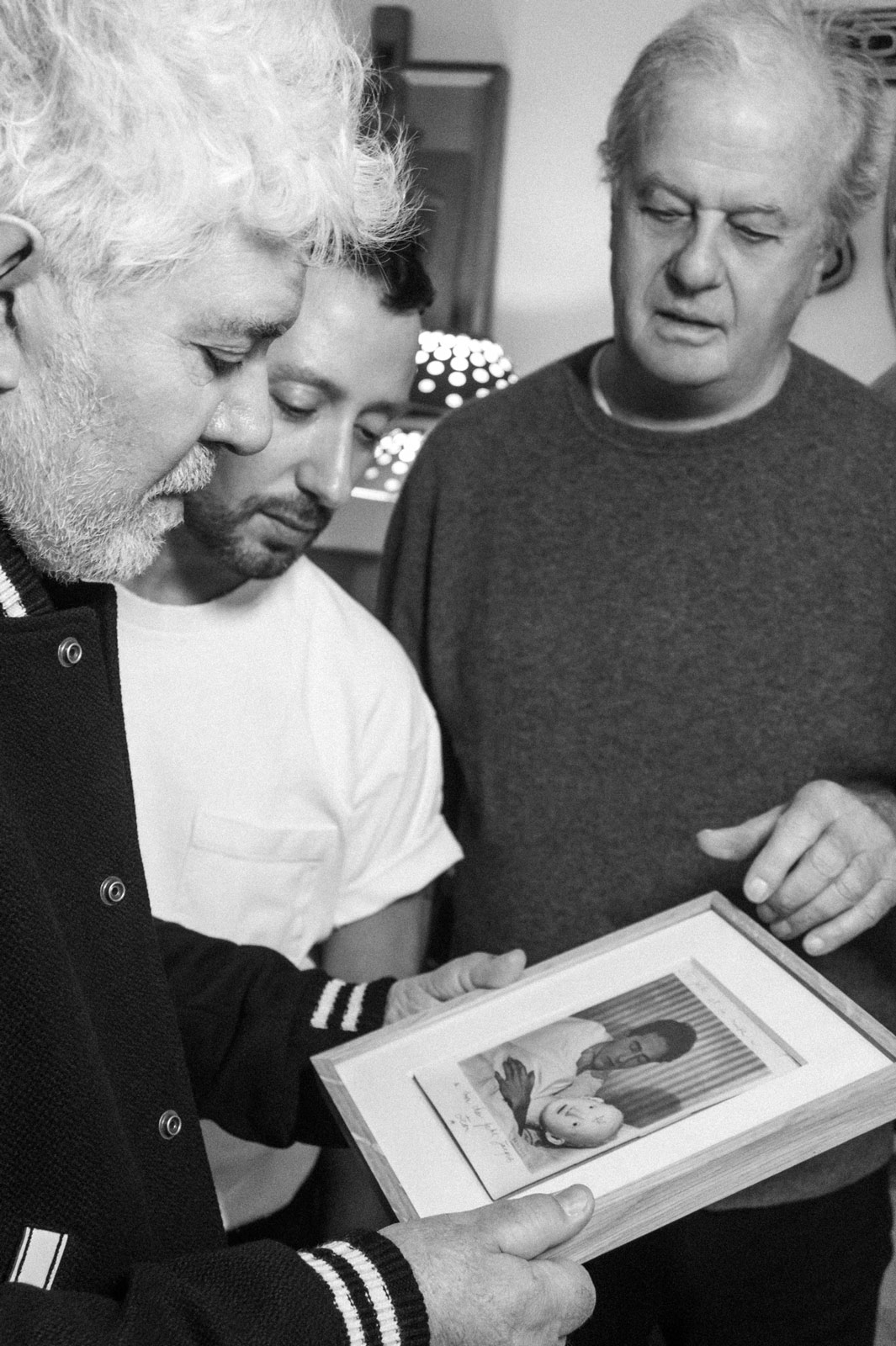

Pedro Almodóvar: I’ve known Anthony’s work since he [started at] Saint Laurent, but the first time we met was in LA in my hotel, the Sunset Marquis. He was accompanied by Philippe [Contini], and very timidly they suggested that they’d like to work with me—not on a commercial, but on a work of mine that they would produce. We didn’t decide on what it would be, just that I would bear it in mind, as I did two years later.

Anthony Vaccarello: I’ve been watching your movies since… forever, probably. When we first met in LA, I didn’t know what to expect, but I knew Pedro’s love and passion [for] portraying women could be a connection between us. It was—and actually, we have way more in common.

Pedro: I think there has always been a dialogue of mutual influence between cinema and fashion. Yves already had a very specific place in cinema through Catherine Deneuve. Belle de Jour is Deneuve, but it’s also Yves Saint Laurent, and of course, it’s Buñuel. For me, fashion has always been very important for defining the characters, or simply establishing the tone of a film.

Anthony: There are these two worlds gravitating in my mind, a series of images and memories, often drawn from cinematographic scenes or fashion statements that come together and blend in my head. It’s as if I’m filming a movie in my head and then do everything possible to bring it to life.

Document: Pedro, why did you choose the Western genre for Strange Way of Life?

Pedro: I had written a very theatrical scene where two former gunslingers—and former lovers—talked while they got dressed in the morning, in the bedroom in which they’d had a very animated night of sex. For both of them, the memory of the night before was present, but they reacted in very different ways: one passionately, and the other as if that night had never existed.

When Anthony spoke to me about collaborating, I thought of that scene and turned it into a script for a half-hour film. I was interested in exploring the sexuality of those characters in a genre [in] which only one kind of sexuality exists. [From the reactions of] the two gunslingers—one of them a sheriff, and the other a rancher, the story grew. I could explain what they had become after 25 years, and how they had survived their feelings in a world in which two men can’t love each other, much less think of a future together. The film gives an answer to what would have happened if the characters of Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in Brokeback Mountain had continued together when they were older.

Anthony: Sometime after our meeting, Pedro said this was a project he had in his head for almost 10 years, and that’s exactly what this project is about: letting creative thoughts come to life without being limited by any kind of compromise. I wanted to make one of his fantasies come true.

“For me, everything starts with having no ‘musts’—a place in which there’s no need to pretend to be a certain way just because someone else is telling you this is the right or the cool thing to do. Who cares? ”

Document: Pedro, you’ve said you don’t like making films in English because you are not familiar with American society. Why did you break your rule?

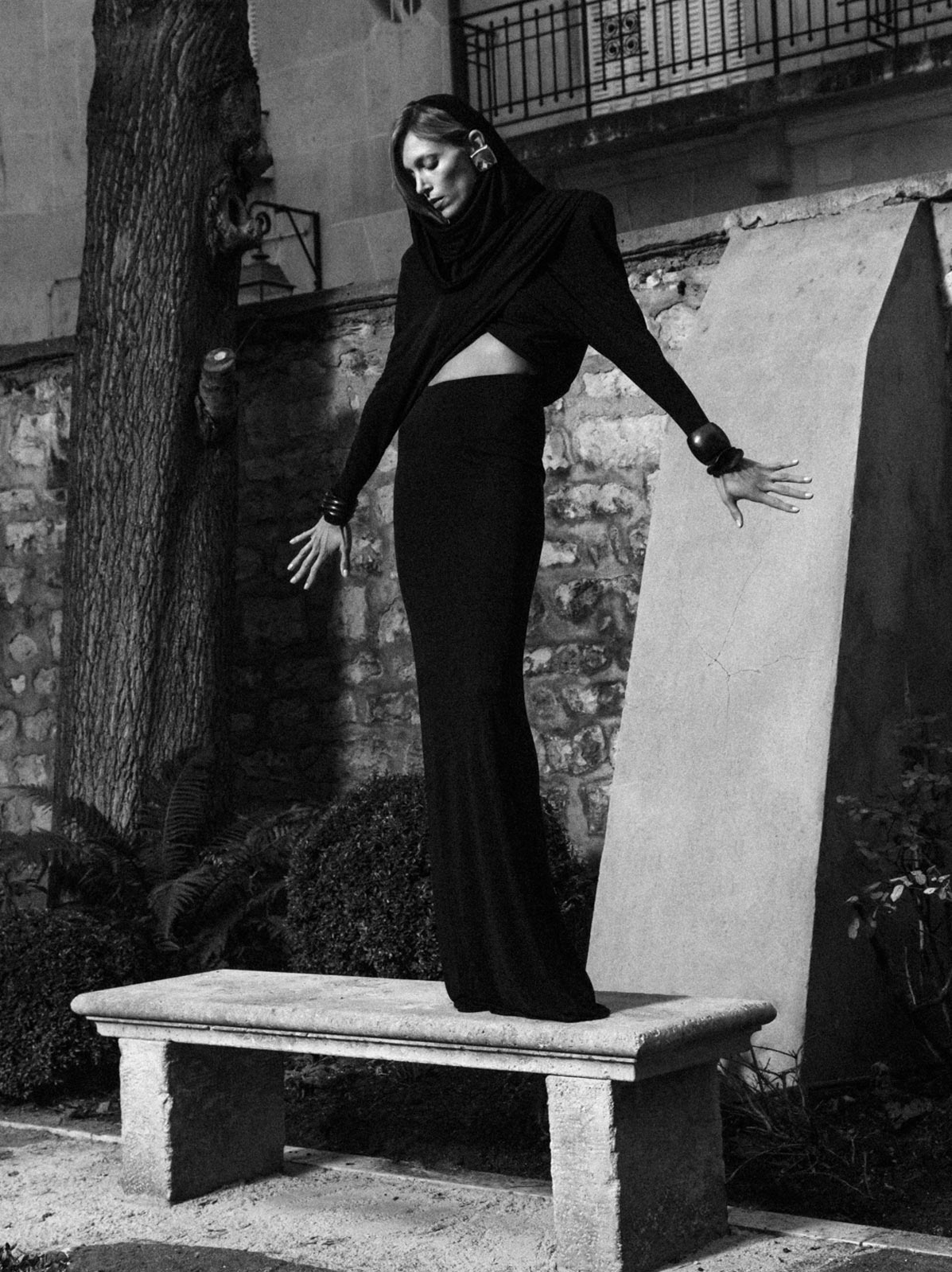

Pedro: I was talking about other kinds of stories, contemporary stories that talk about everyday life. In a genre like the Western, the action and characters are inspired by the information that cinema itself has given about American history. I’ve taken the films in this genre as a reference in every sense—for the action, the clothes, the sets, the hairstyles, the jewelry. I’m not trying to give a naturalistic portrait of how two former gunslingers lived in 1915, but of how cinema talked about them. In fact, we shot on sets that already existed, in Almería, created by Sergio Leone for the films he shot there with Clint Eastwood.

The Western is a genre of male characters in which—except for a few contemporary exceptions—there has never been any mention of desire between two men. That was the attraction, talking about desire in a genre that hasn’t allowed that until now. The version of masculinity that Hollywood and the spaghetti Western have given us is one-directional, conventional, and orthodox: the man defends the family or hires himself out. He defies other men, he defends the land, and his love life is marked by just one woman. I adopt a classic genre so that the male leading characters can talk about their own sexualities in a way that, until now, would not have been allowed.

Document: Anthony, what are some of your favorite characters in cinema?

Anthony: Anna Magnani in [Mamma] Roma by [Pier Paolo] Pasolini, Hanna Schygulla in [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder’s films, and all the women in Pedro’s films.

Document: Pedro has said that women always offer better characters.

Pedro: At least in Spanish society, the woman is always more spontaneous than the man, and therefore, much richer, dramatically speaking. When a man is abandoned by the woman he loves, the man suffers as much as any woman. We belong to the same species. But the man reacts differently; he gets drunk and bores his friends or he kills the lover. The woman, on the other hand, goes out on the street, because she can’t bear waiting at home for the man who is going to say goodbye to her; she has no sense of [feeling] ridiculous or shameful in showing that she is hurt. She tries to find out everything that the man has hidden from her and fights to defend what has already been broken. I can make Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and it’s an entertaining, dynamic comedy. But I’m sure that Men on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown would be much a more boring film.

Document: How do themes such as liberation and seduction shape your work—like in Pedro’s case, inspired by La Movida?

Pedro: My cinema came into existence at a time when Spain was opening up to a democratic society, and young people could enjoy all kinds of freedom. Neither my films nor my life would have been possible at another time in history. There was no censorship and my characters’ relationships are as free as our own nature allows.

Anthony: For me, everything starts with having no ‘musts’—a place in which there’s no need to pretend to be a certain way just because someone else is telling you this is the right or the cool thing to do. Who cares? I genuinely believe that when those pretentious intentions fall, what’s left is the most interesting personality.

Talents Betty Catroux, Tara Falla, Anja Rubik, Milena Smit, Vassili Schneider. Hair Pawel Solis at Artlist using Oribe. Make-up Karin Westerlund at Artlist. Props Stylist Dimitri Levas. Manicure Alexandra Janowski at Artlist. Photo Assistants Zac Rupprecht, Jérémy Tellier, Stefan Rappo. Gaffer Quentin Ameziane. Stylist Assistants John Handford, Kenny Paul. Tailor Simone Torpenn. Hair Assistants Aimie Benanan, Fanta Kadiakhe. Make-up Assistants Thomas Kergot, Lauren Bos. Production Cinq Étoiles Productions. Cat Trainer Florence at Fauna Films. Post Production Matthew Richards.