Vignettes from O, Miami Festival: bee-keeping, traffic, and readings cementing a quick-changing city’s literary scene

The fire hydrant is first to greet us. “Welcome!” he says. “You must be here for Dogleggers!” Dozens of Miamians and their pets are gathered at—er, under—The Underline, the first segment of a proposed 10-mile-long, super-skinny park running beneath Miami’s Metrorail. The official website for The Underline depicts happy Miamians doing yoga, riding bicycles, and walking dogs among slivers of greenery and public sculpture as the train glides overhead; digital renderings of a proposed future made slightly more real by the real people and real dogs (all good boys!) mingling under the generous penumbra of the track.

I ask the hydrant what his name is. He adjusts his foam physique.

“Hydrant,” he says. “First name, Fire.”

I’d been traveling for almost a month, mostly around New York and Long Island, towing a ridiculously large and fluffy cerulean scarf that had acted as both cold weather accessory and provisional plane pillow. I touch down at Miami International Airport and throw it in the trash. I haven’t felt hot air on my face in weeks. The stretch of South Beach just outside my hotel is being packed up for the day. Ostensibly open to the public, sections of coastline are claimed each morning by neat rows of chaise lounges and umbrellas from beachfront hotels, reserved for paying guests. Bright yellow construction cranes and frontloader trucks idle just steps from the water. I wonder, perhaps naively, how they don’t sink into the sand. I have tucked 10 or so pages back in my journal, the beginnings of a poem—the first I’ve tried to write since I was a teenager—hoping, perhaps naively, to emerge from this weekend with feedback on it.

I am here for the opening weekend of the 12th annual O, Miami Poetry Festival, whose mission is for “every single person in Miami-Dade County to encounter a poem” during the month of April. O, Miami was founded by poet P. Scott Cunningham in 2011; the first iteration lasted two days and was modeled more on the academic symposium. It’s since ballooned into a thrumming nonprofit with a full-time staff and dozens of volunteers who, in addition to running year-round poetry and art workshops in public schools all around Dade County, lend their time to making the sprawling festival come to life. They are identifiable by t-shirts that read, MIAMI IS A POEM WE WRITE TOGETHER. There is no model. There is Dogleggers, my first stop: a mash-up event combining the services of the Bookleggers Library Bookbike with on-site dog adoption—hosted by the boarding and dog-walking service PAWS Miami—along with a dog-themed photo booth and dog-themed poetry on-demand, courtesy of local Miami poet Lysz Flo. Flo sits behind a typewriter under an awning. I want to see a dog get a poem. I zero in on Gigi, a honey-colored chihuahua with a pink cleft nose that looks like a swirly guava bun cut in half. “She was found on the streets of Hialeah,” her owner Cucy tells me. “If you want a dog, go to Homestead or Hialeah.” Three people nearby chuckle.

Proper nouns elicit laughs here like nowhere else. Miami-Dade County is the seventh most populous county in the United States. Words are a currency of lighthearted sussing out. Neighborhoods and geographical nicknames are tossed around, tested for recognition, exchanged with appreciation and intimacy. Being a guest of only a few hours at that point, my nouns are scant. Los Angeles analogies are what I have to offer, like fake coins: palm tree, sun, beach, traffic. At Dogleggers, I meet Melissa, the communications director of O, Miami. She hands me a tote bag stuffed with programs and stickers and maps and several books from the nonprofit’s publishing arm, including an anthology titled Waterproof: Evidence of a Miami Worth Remembering. The tote bag bears a quote from poet and theorist Alexandra T. Vazquez: I remain with the mangroves.

“I have tucked 10 or so pages back in my journal, the beginnings of a poem—the first I’ve tried to write since I was a teenager—hoping, perhaps naively, to emerge from this weekend with feedback on it.”

“I hear you’re from Los Angeles,” she says. “We’ll have to compare LA and Miami traffic.” Discussion of traffic in Los Angeles is a trivia competition—something locals don’t really partake in. Discussion of traffic in Miami, I learn, is a team sport, and also a gesture of deference. Three of my three Uber drivers, so far, have apologized for it.

Gigi is ready for her poem. An assistant in her MIAMI IS A POEM WE WRITE TOGETHER shirt asks Cucy a few questions to help Flo get going: What are three words to describe Gigi?

“Vocal. Sassy. Sweet.”

What is a sound you love that you associate with Gigi?

“The sound of her nails on the wood floor.”

Is there anything else we need to know about Gigi?

“She’s really shy.”

I look at the selection of used books Bookleggers curated for the event. There are two sections: One is dog-themed, and the other is poetry. All are free to take. I slip a copy of the Robert Fitzgerald translation of Homer’s Odyssey into my tote. I did not bring a dog to have my picture taken with in the photo booth, so I am lent a cutout of a dog. Gigi’s poem is ready just as the Polaroid of me with the cardboard dog develops:

“Isn’t she lovely”

letting her barks

be known with sass

& classy cowboy hats

with her nails announcing

her approach

a shy pooch

with sweet soliloquies

I forgot to mention, Gigi is wearing a cowboy hat. I am assured there will be time to workshop my poem at some point, but right now we are going to hand out Poetry Parking Tickets—little leaflets designed to look like Miami-Dade County parking tickets, but printed instead with poems written by students who have participated in O, Miami workshops throughout the year. I would like more than anything to witness firsthand a Miamian encountering a poem through this guerilla method—I know the feeling of seeing a red-and-white slip of paper on my windshield and immediately getting pissed off. (Miami-Dade parking tickets are orange and white.) I would like to think I have the kind of poetic constitution to be touched by this sort of good-natured ruse. I walk all around Brickell, putting tickets on windshields, unable to stake-out long enough to catch anyone discovering their Poetry Parking Ticket.

Waterproof is an anthology of “micro-elegies” about places in Miami. When asked, What will you miss when Miami is gone? responses ranged from an essay on the US-1 Northbound, to a poem on the American Airlines Arena, to a remembrance of La Torre de la Libertad, or the Freedom Tower, on Biscayne Boulevard—formerly headquarters of the Miami News, then officially sanctioned as the Cuban Assistance Center from 1962 through 1974, during the regime (reign? tenure?) of Fidel Castro. In her ode, Beatriz Reyes writes, “Even though Cubans had the opportunity to move from one country to another, we still have Cuba in our hearts, and that’s the greatest feeling someone can have.”

Like the inscrutable system of underwater gates and compressed air the Italians are seemingly forever experimenting with to keep Venice from sinking, there is, beneath the chipper marketing and brightly-colored merchandise, a sense of urgency to keep a certain Miami from sinking. Said merchandise includes a cornflower blue dog bandana, also bearing a poem, and a butter yellow baseball cap with the words “sun this / sun that” embroidered onto it, which I am eager to have. “I think those lines were also written by a student,” Melissa explains. “The hat itself is a kind of poem.” I agree.

I thumb through the anthology in the Uber on my way to the cocktail reception that night. I look out the window and wonder how many of the places elegized in this book are still out there, in whatever form, in the city itself.

“[Miami is] a real estate development town and a tourist town, so it’s a place that doesn’t have a long history. At least, that’s the story we can get a hold on… In every other city I’ve lived in, people would say, ‘You should have been here five years ago.’ And here, it’s, ‘Just wait five years.’”

O, Miami’s official opening night event, billed as a conversation with poet Hanif Abdurraqib and Alexandra T. Vazquez “as they discuss how music and other cultural activities forge a sense of place,” takes place at the Black Archives Historic Lyric Theater in Overtown. I arrive early for the reception in the lobby. The napkins, placed down on the open bar to catch spills from citrusy spirits, are printed with a poem in English: Your kindness makes / my smile shine. / I love when you shine / as bright as the sun; and a different one in Spanish: Si tu eres la luz que brilla / yo soy la oscuridad que / espera en las sombras; along with the O, Miami logo. Congresswoman Frederica Wilson is there, in a rhinestone cowboy hat, holding court with a circle of constituents. She looks fun. I want to talk to her, but I’m not sure what to say. I don’t think she would be open to workshopping my poem.

I have yet to meet Cunningham, O, Miami’s founder. I see him talking to Abdurraqib in the lobby and introduce myself. “We were just talking about place,” he says. When I say I’m from Los Angeles, he reorients, referencing both Mike Davis’s City of Quartz and Rosecrans Baldwin’s Everything Now. I admit to Abdurraqib that I am a longtime admirer. I didn’t know that he was primarily a poet when I read, in 2020, a breathtaking essay on the 1998 romcom You’ve Got Mail, of my favorite guilty-pleasure movies. “Desire has a key for every lock,” he wrote then, “if a person allows for it.” Abdurraqib graciously accepts my praise, and we all meander together into the subject of popular movies and what level of critique, exactly, they invite. “The rom-com is high art,” Abdurraqib insists. Conversation is an art of opening doors—and what I find over my visit is most poets, and Miamians, each carry their own set of keys.

I run into Melissa again, and she offers me a tote.

Once inside, the 400-seat theater is at capacity. We are welcomed by Camila Pritchett, Executive Director at the Black Archives History and Research Foundation of South Florida, who gives a brief historical sketch of the Historic Overtown, “first known as the central Negro district, or color town. [It] was not the chosen space, but a space that black people were relegated to, as they were excluded from the community at large. But what was born of that exclusion? The creation of a community that was an arts and entertainment mecca for the people who lived here. The sense of place cultivated by artistic expression was evident in the neighborhood’s nickname as the Harlem of the South.”

Vasquez and Abdurraqib both read from recently published books, then are joined on stage by Cunningham. Among a literary community in Miami, where words are clearly valued, the specter of Joan Didion, her “vision” of the city, looms subtly in the background of the group mind gathered here. I tried to read Didion’s 1987 book Miami on the plane on the way over, but finding the first few pages stuffed with descriptions of plaques, it did little to prepare me for this trip. Though, at one point during the on-stage conversation, Vazquez, an accomplished theorist and professor of performance studies at NYU, hits on the Didion thing, which is really just one instance of the kind of encounter almost every writer has upon connecting the words of another with one’s own experience; realizing that writing is a kind of world-building. “I remember, when I was young, seeing Joan Didion’s book Miami on the bookshelf. There are some problematic things in that book—but as a kid, I was like, Oh my God, you can write about this place…”

“You’ve created the perfect segue.” Cunningham laughs. “Thank you. I don’t want to talk about Joan Didion’s Miami, but there is a Joan Didion quote about place that I wanted to bring up. It’s actually from The White Album. It’s a quote that I both love and struggle with. She’s writing about Hawaii, but it doesn’t really matter. She says, ‘A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically, that he remakes it in his image.’ I love this quote, but there’s also a possession in that—that I don’t, like, personally feel comfortable with in terms of Miami. You know what I mean?”

The crowd murmurs as one in reply.

The next day, I suspect I have gravely misread the purpose of the festival, in assuming that I would be able to workshop a poem during said festival. Today, I am assured, I am being sent to a workshop where participants are encouraged to create poems. And work with beeswax. The connection between poetry and bees might seem slight, but I know: All beekeepers are poets. I’ve known this since high school, when I voiced a vague interest in bees (mainly as a possible tattoo) and an intense boy gave me a copy of John Festus’s 1974 classic Beekeeping: The Gentle Craft—a practical guide to amateur beekeeping, wherein the author describes the decision of whether or not to keep bees as “a winter of madness.”

About 20 Miamians, plus me, are sitting in a circle in Oak Grove Park. Angular limpkin birds pick their way around the nearby lake. We are here for Mind Your Beeswax, a workshop incorporating the art of candle-making, poetry, and the collective nature of bees, facilitated by the beekeeping duo known as Combcutters. Sarah, a production assistant for O, Miami, kicks off the proceedings. “I’m Sarah, a production assistant with O, Miami. If you’ll look in your tote—hopefully, everyone got a tote—you’ll find a program. Most of our programs are initiated by Miamians through an open submission process, so take a look and consider submitting an event for a future festival.”

Events and phenomena lined up for this year’s festival include ice cream tastings with flavors inspired by poems from students in O, Miami’s education program, a Dolly Parton-themed online workshop called Islands in the Stream, a children’s poetry open mic called Poetry in Pajamas, the unveiling of several public artworks incorporating poetry, and another online workshop called Translating Place in Poetry, which is probably what I’m looking for, but is not taking place during my visit. Right now, I am here—with the limpkins, and the bees, and the dappled shade.

Combcutters was started by Rebecca Wood and Sam Pierre-Louis; they tend to urban hives all over Miami-Dade County, and use beekeeping as a springboard for workshops on everything from consensus-building, to mathematics, and today, to poetry. “To work with bees,” Rebecca says, “you have to breathe deep and work slow and conquer fears.” We go around the circle and say our names and pronouns. A girl named Melissa—not the one who works for O, Miami—reveals it’s her birthday today, and we all clap. We do a word-association exercise, yelling out responses to prompts like wax and transformation. We learn how honey, like poetry, helps forge a sense of place. “We find that every neighborhood’s honey tastes different,” Rebecca says. “We are sitting in the flavor of those bees.”

The luminaries are to be cast from full water balloons lowered into hot beeswax. Next to our circle of chairs is the candleholder-making-assembly-circle, with stations for dipping, cooling, and observing an active hive. We are each handed a water balloon, incredulous that they will remain intact—but they do.

“Miami has an atmospheric kinship with Los Angeles. There is heat and cars, skyscrapers that look like towers of ice, little incursions on the urban landscape that get taken for magic.”

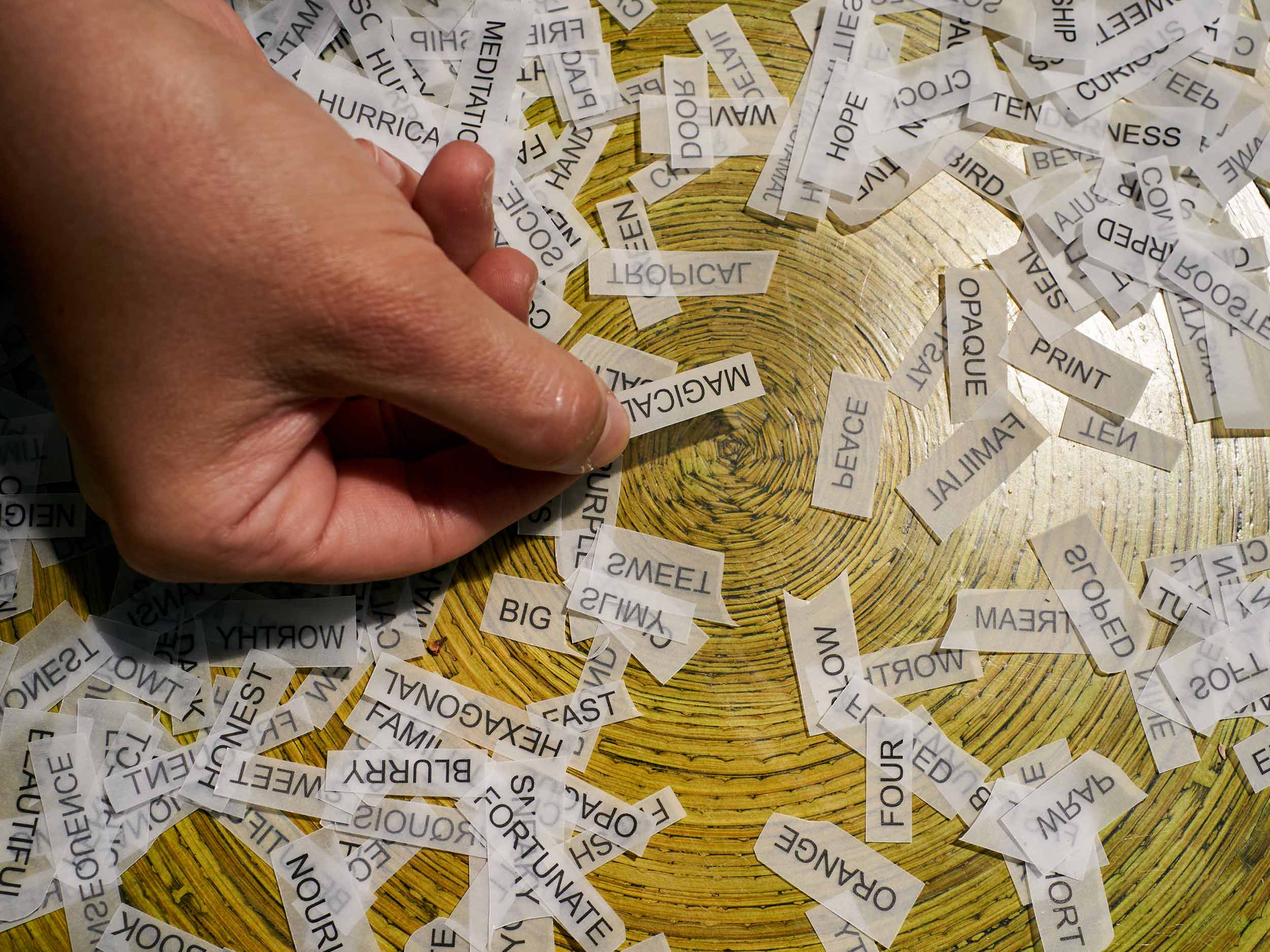

We make our way around the circle, dipping balloons into crockpots and picking out bits of plant matter and words for our poems. The words are printed on cut squares of translucent paper, and divided by parts of speech. It is calculated that we’ll need exactly 10 dips in the wax. No more, no less. Ten dips is the right amount to create a luminary thick enough to not melt from the tealight, but thin enough to glow when lit. The group identity forms around discussion of dip methods. Strangers sidle up to one another and ask, “What dip you on?” in low tones—as if each dip is a year of sobriety. Some of us giggle at the stalactite of wax that gathers at the bottom of our balloons, because it looks like a nipple. By dip seven, mine somehow has four beeswax nipples, like udders. I show mine to Susie, a massage therapist. “Mine has four nipples,” I say. “Beautiful,” she replies. “More food for the rest of us.”

After 10 dips, we splinter off into smaller groups to work on decorating our luminaries. I sit with Susie and Melissa, who is turning 21 today, her sister Emily, and another O, Miami production assistant named Marie. “Why aren’t you out drinking?” I ask Melissa.

“Oh, stop it,” Susie says. “There’s always going to be beer.”

“It’s crazy, because my name in Greek means honeybee,” Melissa says. “So I thought, if there’s a bee-event, with poetry, on my birthday, I have to do it.” I ask if bees are finding their way into her life in other ways.

“I am going to Spain to teach English soon. I got placed in a province called El Colmenar Viejo. And colmenar means, like, where the bees would be kept.” We all agree that the universe is sending Melissa to Spain. We are encouraged to think of a special place in Miami as a prompt for our poems. I am a guest here, so I string together a bunch of prepositions and bougainvillea petals as an ode to my hotel bed. A spider, larger than any arachnid I’ve yet seen, drops onto our picnic table and jumps onto Marie. I scream. Emily and Melissa laugh. “Hold still!” Susie says, gently scooping up the creature and placing it on a nearby tree.

What the fuck was that? I ask.“A banana spider?” Melissa says

“She has the legs of a banana spider. She has a silver body,” Susie replies, turning back to pasting little slips of words on her beeswax luminary. “Maybe she’s had some work done.”

Miami has an atmospheric kinship with Los Angeles. There is heat and cars, skyscrapers that look like towers of ice, little incursions on the urban landscape that get taken for magic. In LA, it’s the sight of movie sets. Here, it is the persistence of fauna. I’ve almost stepped on two butterfly lizards. On my last day, I meet Cunningham on the outdoor patio of Paradis Books & Bread in North Miami. Paradis makes chic, rustic breads and offers an array of wines. It also has shelves full of books for sale, organized and labeled by subjects like “Haitian History,” “French Theory & Its Fallouts,” “Black Studies,” “Italian Marxists,” and “Carceral Studies.” The bakery is collectively owned by its workers, which accounts for their general sunny disposition. I take my cold brew and my black sesame cookie (honestly, the best fucking cookie I’ve had in years) and sit down, sweating and I hope not too unpoetic-looking.

Cunningham apologizes for the long ride, and I thank him, genuinely, profusely. I will never make fun of anyone who complains about LA being too spread out again. Sprawl feels different when it’s your own. Every event I attend has been at least a 45-minute car ride from wherever I was before. I lose count of how many times I crisscrossed Biscayne Bay, where tourists zip around on jet skis and locals park off the side of the banks to fish, or picnic, or just push the seat back and listen to music. My poem remains un-shopped, but I still carry it home. I have my hat, and my tote, and my beeswax thingy, which I will accidentally leave in the Uber on the way back to the airport and feel unreasonably sad about.

“Honestly, it’s a difficult festival to visit,” Cunningham admits.

“So you admit it!” I say.

“Absolutely, because it’s for locals. The point is to be able to reach people from Aventura and Homestead in a month. In the northeast, those would be in two different states, you know—in terms of actual mileage.”

I ask what he hopes to achieve by courting exposure for such a local event.

“It’s a great question,” he says,.“I don’t necessarily think I want people to be starting O, Miami’s all over the country.”

“But what about O, Idaho, or, you know, O, Montecito.”

“I mean, one answer to that is, like, people have already done it.”

“What am I doing here, Scott?” I ask. He laughs. Then gets serious.

“I’m advocating for regional literature.”

He asks me if I see any parallels between Miami and Los Angeles. I say that certain parts of Miami remind me of certain parts of LA, but in a sad way.

“Everything seems to be under construction. Everything gets fully dozed every 50 years. And, in a way, that creates the feeling of not having a history.”

“That’s it, isn’t it?” he says. “Miami changes so incredibly fast. It’s a real estate development town and a tourist town, so it’s a place that doesn’t have a long history. At least, that’s the story we can get a hold on. It’s not exactly true. But it’s a convenient story. Because if there’s no history, then if we change something, if we tear something down, it doesn’t matter. Because it’s positioned as, We’re building something new. It’s all about the future. In every other city I’ve lived in, people would say, ‘You should have been here five years ago.’ And here, it’s, ‘Just wait five years.’ But there are pros and cons to that mindset. The cons are that this town loves to erase things and people and communities. And I think literature and arts can be somewhat of an antidote to that. Hanif put it so well in the poem he read the other night. What was the line?”

I remember it well: “Permanence is the greatest stunt of them all.”