The Saint’s legendary annual bacchanal shut down after 40 years, signaling a bittersweet transition in the landscape of queer life

During COVID-19, I worked on a casual writing project. I found and interviewed gay men who experienced The Saint, a gay disco that operated in New York City’s East Village from 1980 to 1988.

Over its lifespan, The Saint was considered the best disco in the world. The men I interviewed said it would never be replaced—that nothing like it could exist again. They were all survivors of the AIDS era. They told me about the men they once danced with, men they lost. From those interviews, I learned that AIDS, its destruction of gay life, and its brutal social backlash forced the great club to close after only eight seasons.

Sadly, the project went nowhere. Other gigs came. I moved on. But I wish something had come of it, because these stories form a chapter of gay history which few voices are left to tell.

“There was a great sense of uplift and empowerment that came out of The Saint,” said Alan Poul, now a Grammy-winning film producer. “It wasn’t preordained that it would end with death and disaster. It was not deserved. It’s just something that happened. But the virus doesn’t have the right to retroactively color the wonder and joy of those years.” The interviews were often painful. Poul and I cried on the phone.

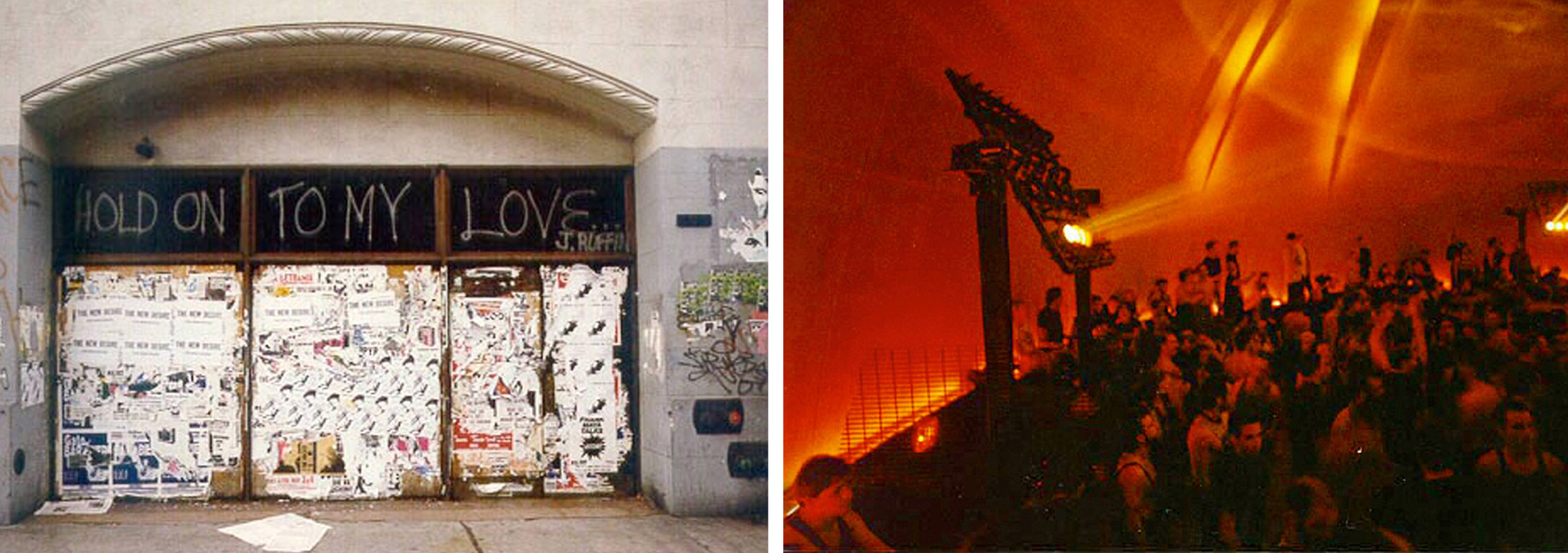

The Saint was a destination—a pilgrimage for gay men across the world. It was known for its wild parties, the most famous of which was the Black Party. When the disco closed, an organization called The Saint at Large was formed to continue them. At first, it worked—but over the years, the parties stopped. Except for one.

This past March was the fourth year of gay life without the Black Party. If you are straight, you likely do not know what the Black Party was. Its delights were mostly kept secret. As cell phones became ubiquitous, and everyone had a camera in their pocket, you had to check them at the door.

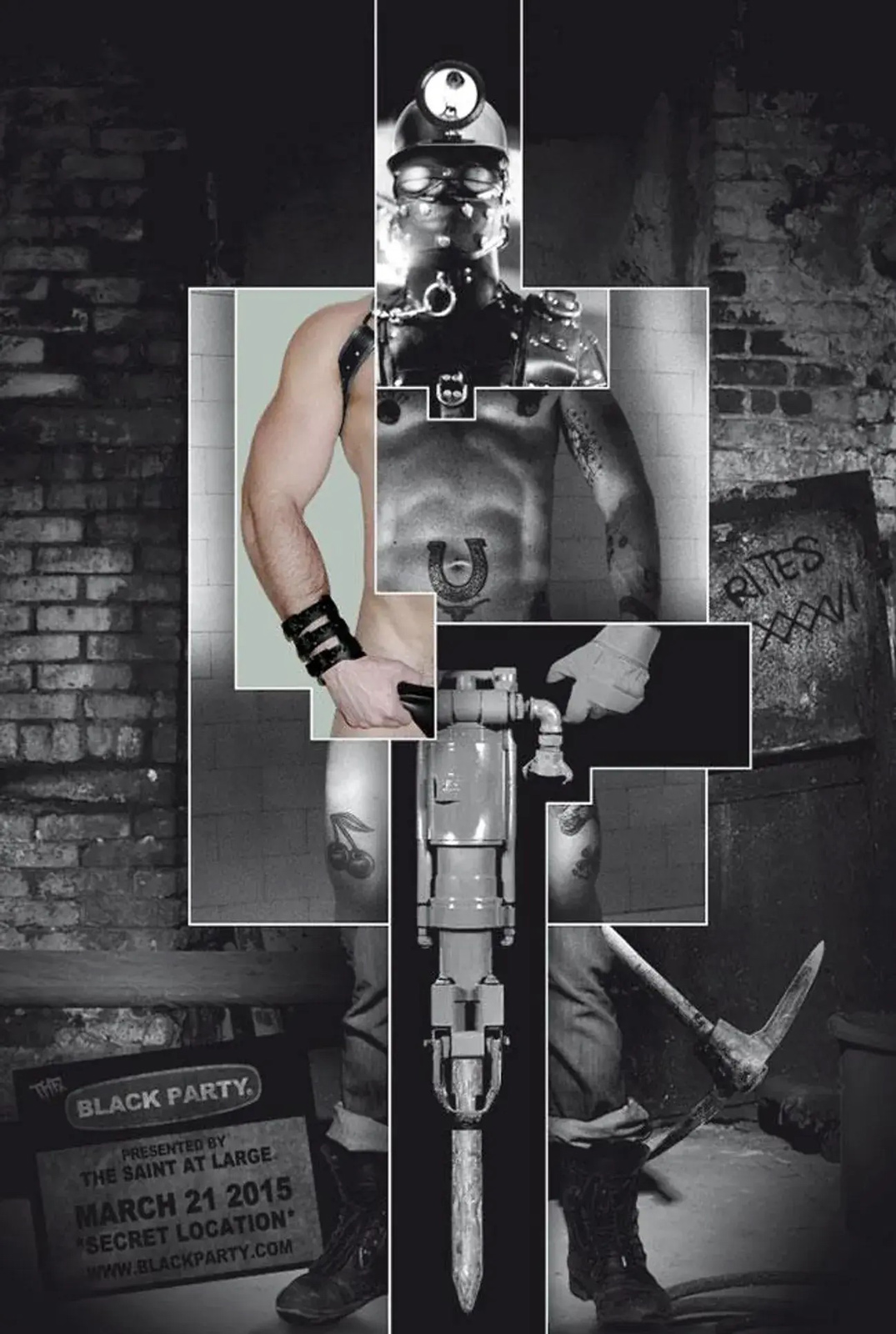

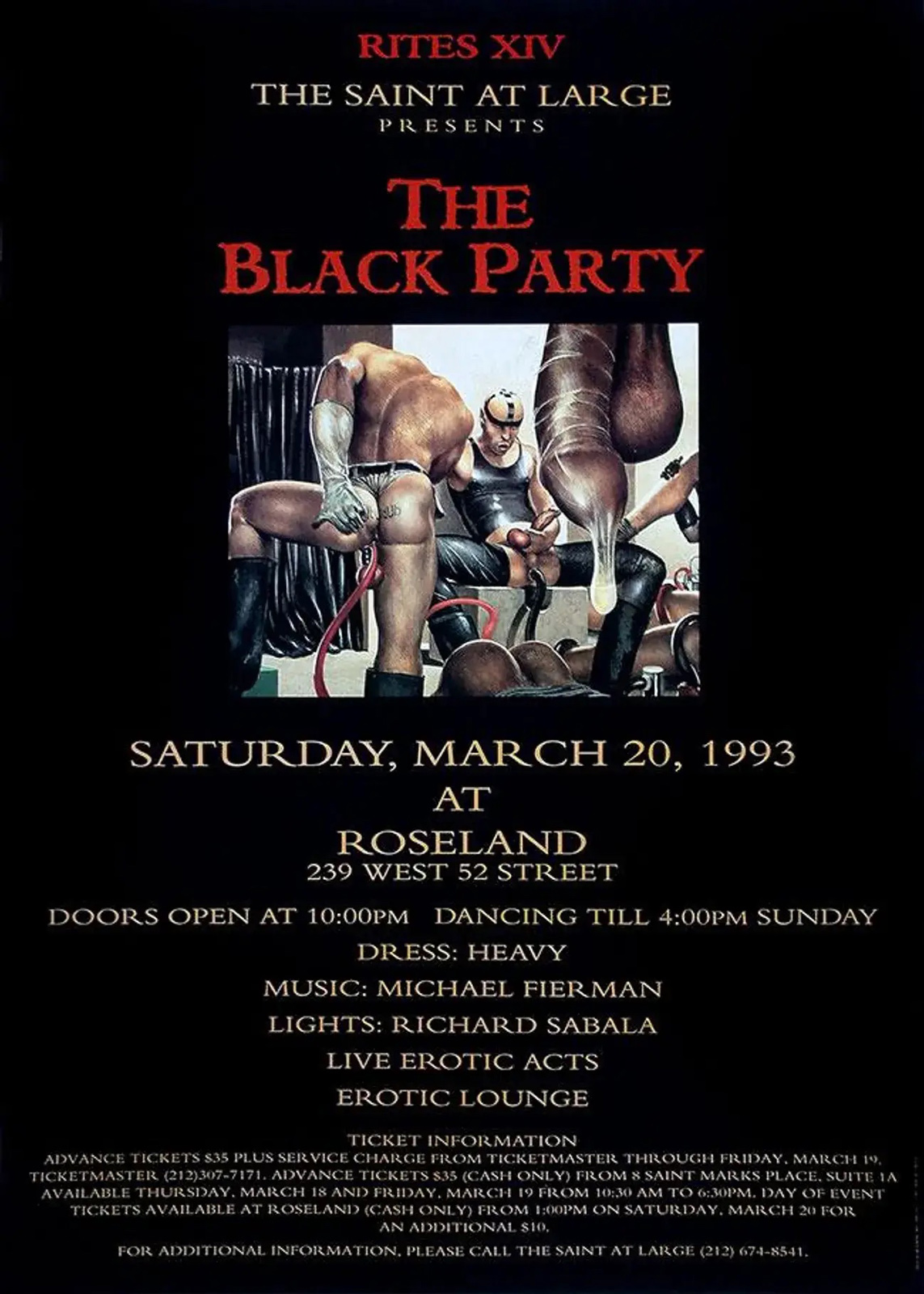

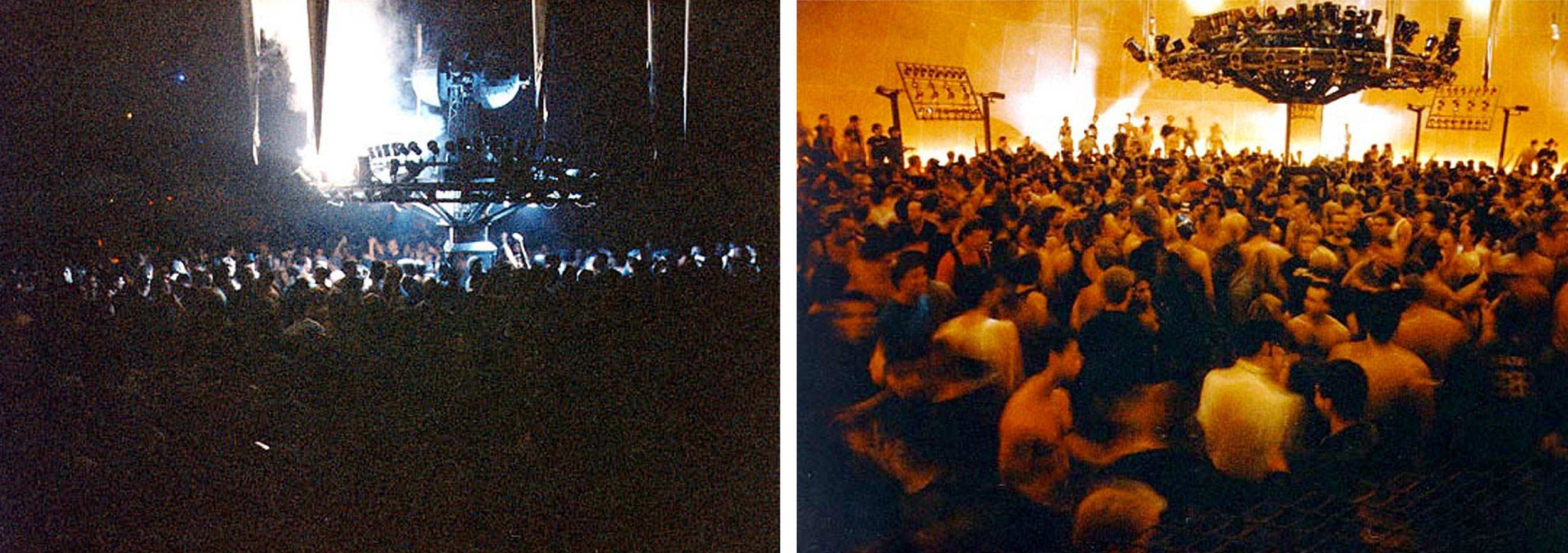

It was, at its simplest, a bacchanal: two days of dancing and sex somewhere in New York City. Locations changed—it moved from warehouse to warehouse; from the Roseland Ballroom (for 24 years, before it closed) to venues across all five boroughs—but its thrills stayed the same. The party happened yearly around the vernal equinox, known in pagan lore as the “rites of spring.” It was famous for its fetish vibe, extreme dress code, elaborate themes (barnyard, submarine, outer space), extensive sex areas, and “strange live acts”—from hardcore bondage to a live boa constrictor sliding in and out of a man’s anus.

Unlike most dance parties, the Black Party had the spirit of an immersive art exhibit—like a huge haunted house, with world-famous DJs acting as guides for attendees, often numbered in the thousands. They took a musical journey that ended with a glorious morning set, comprised mostly of disco. At that point, the lights got brighter. Everyone lifted their hands. People cheered. It was unity and love and music.

In 2019, I wrote about the 40th anniversary of the Black Party for Them, a queer magazine. At the time, I was no stranger —I went every year—and I struggled to maintain a reporter’s neutrality. I withheld praise and thanks as I interviewed DJs like Robbie Leslie and Michael Fierman. I also spoke to Stephen Pevner, CEO of The Saint at Large. None of us knew it then, but that would be the last party. The next year was 2020, and the pandemic would shut down the world.

Over the course of the party’s 40-year life, Pevner tempted the press that each iteration would be the last. I think this was mostly to sell tickets. It is true that he faced—and still faces—a costly lawsuit over the party’s ownership (more on that later). But somehow, as time passed, he and his team scraped by. Dance parties can be low-profit endeavors, especially as rental spaces in New York grow more expensive. Ironically, that year’s theme was “Caligula: The Last Party,” named after a Roman emperor famous for his wild hedonism. Pevner did not actually intend it to be the last—the name was just a name. In 2020, he scrambled to make an event happen before canceling at the last minute as COVID cases skyrocketed in the city.

Many bars and clubs closed forever during COVID-19. Though social life has mostly returned to normal, in New York and elsewhere, Pevner’s legal troubles have ramped up, and things look grim for the party’s return.

The original owner of The Saint was named Bruce Mailman. He was a nightlife impresario, owner of the New St. Marks Baths—another famous gay destination of 1980s New York—and Pevner’s older cousin. Less than six months before he died of AIDS-related complications in 1994, Mailman married a woman, his longtime friend Lucienne Reed. The marriage was a clever scheme to transfer his wealth and assets—including a luxurious Manhattan loft, art by Andy Warhol and Keith Haring, and other treasures—to his partner, Dr. John Sugg, as the two men could not get married.

“It was like the back rooms of seedy gay bars, like bathhouses: vanishing relics of an era from which today’s broader queer culture has moved on. And maybe that’s inevitable; maybe, it is good. We can only move forward.”

After Mailman’s death, Sugg married Reed, who transferred Mailman’s estate to him. The pair were married in name only. They resided in separate parts of the United States. (Pevner says Sugg lived “nomadically,” traveling around in an RV.) Still, their bond lasted until Sugg died in 2016. A year later, Reed filed a lawsuit against Pevner, accusing him of refusing to hand over the assets she deems her rightful inheritance by marriage—ultimately claiming ownership of The Saint at Large.

At the time of his death, Mailman’s estate was valued at $37 million. It includes ownership and licensing of The Saint at Large and the Black Party, along with 40 years of gay nightlife memorabilia and art—much of which Pevner himself collected. If he loses the fight, The Saint at Large and the Black Party will belong to a straight person and her descendants—people who may not save any of it, and likely won’t organize an expensive and time-consuming party for gay men.

It can be easy—tempting, even—to summarize gay culture as effervescent and ephemeral, a constant parade of fashion, drugs, and parties. My friends who did not experience the Black Party—and now likely never will—won’t understand how it made gay culture feel like an honor. Men came from everywhere to dance in a place that celebrated our creativity and our sex. The Black Party survived AIDS. It was a testament to us—to our ability to find joy in the darkest times. Bullied teens and rejected sons celebrated in that most ancient of human traditions: sharing a beat, dancing to a song.

Because of Pevner’s legal battle, he could not tell me much. But he did say to wait: A decision was coming soon. And it did.

On the day I submitted this piece, Pevner informed me that—after more than five years of back-and-forth amongst lawyers—his motion to dismiss Reed’s lawsuit was denied. Now the “true” court case will begin. Pevner must respond to Reed’s allegations, a time-consuming and expensive process of verifying who, actually, legally, owns The Saint at Large.

In any case, four years have passed. New York has grown more expensive. Gay life has moved on. I moved on, too: I went to Berlin, where rumors float that Berghain—the new Saint, according to some—will likewise close soon. What will happen when all our spaces go?

Gay spaces matter because gay men matter. But the word “gay” itself is different. It broke open, became queerer, less definable, more fluid. I did not see the Black Party as queer. I saw it as gay: something for faggots, old-school, dark and hard. It was implicitly—if not explicitly—male-only. It was like the back rooms of seedy gay bars, like bathhouses: vanishing relics of an era from which today’s broader queer culture has moved on. And maybe that’s inevitable—maybe, it is good. We can only move forward.

But I’ll never forget that last party. I remember my look for the night: fishnet stockings, rubber gloves, horns. I got high, danced for 20 hours, had sex with dozens of strangers, and went home blessed. I felt connected to men who lived and died before I was born, men who danced like this, who recognized how important it is to feel freedom and joy after life in the closet. Dancing at the Black Party felt like arriving in the world at last. For 40 years—a brief moment in the grand scheme of things—it was beautiful, and it was all ours.