Following the release of her book, the designer and researcher speaks on information activism, the art of collecting, and the power in rendering grassroots technologies

Cyberfeminism is hard to define, which is part of its enduring appeal. It’s malleable so that it can fit within a range of thoughts, artworks, and movements. Loosely, cyberfeminism can be used to describe any work that engages with questions of technology and gender—upending dominant narratives about masculine ownership of the internet and how it’s been developed, for example. Its scope is diverse, ranging in form from art group VNS Matrix’s Cyberfeminist Manifesto (1991)—which called cyberfeminists the “saboteurs of big daddy mainframe”—to Kurdish feminist organizing online, to the open software exchanges created by Colombian and Brazilian women.

All of these projects—and more—are brought together under Mindy Seu’s new book and collaborative web project, Cyberfeminism Index. Published by Inventory Press, it documents many of the movements and moments that can be categorized as relating to cyberfeminism. It brings together what Seu describes as “a rhizomatic web of global references, including Black cyberfeminism by Kishonna Gray, Xenofeminism by Laboria Cuboniks, glitch feminism by Legacy Russell, hackfeministas by the Cyborgrrrls, 넷페미 (netfemi) by Femidangdang, Eastern European cyberfeminisms by Irina Aristarkhova, and indigenous futurism by Skawennati.”

At a time when one male tyrant can sink an entire social network (and the communities that depend on it), corporate control of culture and the internet are rising in tandem, and surveillance is an expected byproduct of being online, Cyberfeminism Index offers a counter-narrative to how we may think about technology.

Following its print release, Seu joins Document to expand on her creative processes, the globalization of technology, and rendering the near-indefinable tangible.

“I never intended for this to become a capital-P project. I was only trying to compile a reflection of what I saw in my online world as a resource for myself, and it happened to resonate with other people.”

Sanjana Varghese: What were you doing when you came up with the concept for the Cyberfeminism Index?

Mindy Seu: I was a bit lost, and I didn’t have another big project in mind. I was trying to trust emergence, [but] that’s difficult to do for someone who is a future-focused planner. I’m not the kind of designer who is excited by a blank page—images don’t pour out of me. This made me feel insecure, until I realized what did excite me: gathering information, researching, conversing with others. This led to a wealth of context that I could respond to, and the form manifested from that.

I’ve always loved collecting digital things, like links and artifacts, that I could then sort and sequence. This typically leads to resource lists that I share publicly, so others might benefit from them, as well. I started compiling an array of techno-critical works, from theory to practice, essays to net artworks. As I put this online, I asked people if there was anything missing or that could be edited, and it kind of snowballed from there. I never intended for this to become a capital-P project. I was only trying to compile a reflection of what I saw in my online world as a resource for myself, and it happened to resonate with other people.

Sanjana: How do listservs and spreadsheets and those kinds of open-access sharing formats fit into the lineage of the Internet, or being online?

Mindy: Sharing links and listservs feels like part of the origins of the internet. In the 1990s, there were web-rings where people could add a sticker to their website, which would lead to the sites of other people in that network.

You see this all over the media today—there’s always a share button. The intention is different, because now it is focused on broadcasting, but this idea of open source and open access was an emancipatory goal of the early Internet, and some of these strands weaved into what we’re using today.

We began to see an influx of information activism during the height of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement in the US. So many resources, like reading lists, syllabi, and PDFs, were shared through the Google Suite. In some ways, it was basically piracy. But it also became a roving, multi-pronged, open-access library. These modes of sharing have always felt communal, and it’s exciting to see how much these aggregates are becoming a medium unto [themselves]. This act of collecting and editing and sharing feels like an art practice of sorts.

Sanjana: How did you convert the spreadsheet into the website?

Mindy: When the spreadsheet became a website, our primary question was, How do websites age? My collaborator Angeline Meitzler built the bulk of the site, with front-end support from Janine Rosen and PDF generation from Charles Broskoski. How could we make this site as durable as possible?

According to the Internet Archive, the average lifespan of a website is about two and a half years, which is quite short. If that was the case for cyberfeminismindex.com, our site would already be down. I was analyzing several older websites: Some loaded perfectly, some had a lot of broken elements, and some had link rot. The static sites, those that were hard-coded with HTML and CSS without the use of third-party libraries or new languages, aged well with the browser over 25 years. It felt quite durable, so we incorporated this into the design and development of the site.

The trail that you mentioned is what we call a ‘hyperlink trail,’ or a ‘learning trail,’ as coined by my good friend and collaborator Charles Broskoski from Are.na. Everything that you click creates a list of your selections, that you can download as a PDF. So whether you’re selecting intuitively or intentionally, you’re able to build associative links. We don’t store any of the personal information of the person visiting the site, but we do list how many entries were downloaded, and at what time. When you talk to digital archivists, they’ll tell you that duplication is key. Paul Soulellis describes downloading as an act of resistance because we don’t own our content anymore: We access it through streaming services, it’s hosted in the cloud. We upload all of our content to platforms. Storing something on your local machine is an act of preservation—whether that’s the intended purpose or not.

“So many resources, like reading lists, syllabi, and PDFs, were shared through the Google Suite. In some ways, it was basically piracy. But it also became a roving, multi-pronged, open-access library.”

Sanjana: I wonder if there was anything that surprised you about people’s contributions—like, whether people were adding projects you wouldn’t have originally thought of as cyberfeminism.

Mindy: The most exciting part was seeing how it was being shared in other regions, because I would get this influx of entries in different languages, especially in the early days. There would be a lull for a month, and then all of a sudden we’d get an influx of, say, Korean entries, and it was like seeing the physical footprint of digital dissemination.

In a more general way, cyberfeminism encouraged the mutation of its definition, so different groups created their own meanings. In some ways, it doesn’t matter. The idea is for it to be as inclusive as possible, and for it to constantly mutate in definition and form.

Sanjana: What parameters did you have when designing the book? How did changing the materiality of the website prompt you to make certain decisions, or change the project’s resonance?

Mindy: Once something is printed, it has the guise of authority. But this book is intended to feel like a snapshot. It’s not claiming to be finished. It’s not claiming to be perfect. But it does create a document of a moment of mutation of the living online index. That version will continue to crowdsource entries, hopefully in perpetuity, or at least as long as my lifespan.

I was working with my good friend and designer Laura Coombs, and Lily Healey, a programmer and designer. We wanted to create a seamless workflow from the website, to Google Docs for editing, and into InDesign. Lily created scripts that imported all of the content from Google Drive into InDesign. While we hoped this would be ‘seamless,’ we actually had to script each section multiple times, and even after that, there were months of typesetting and editing in layout. It really demonstrates the manual hand that supports these digital workflows.

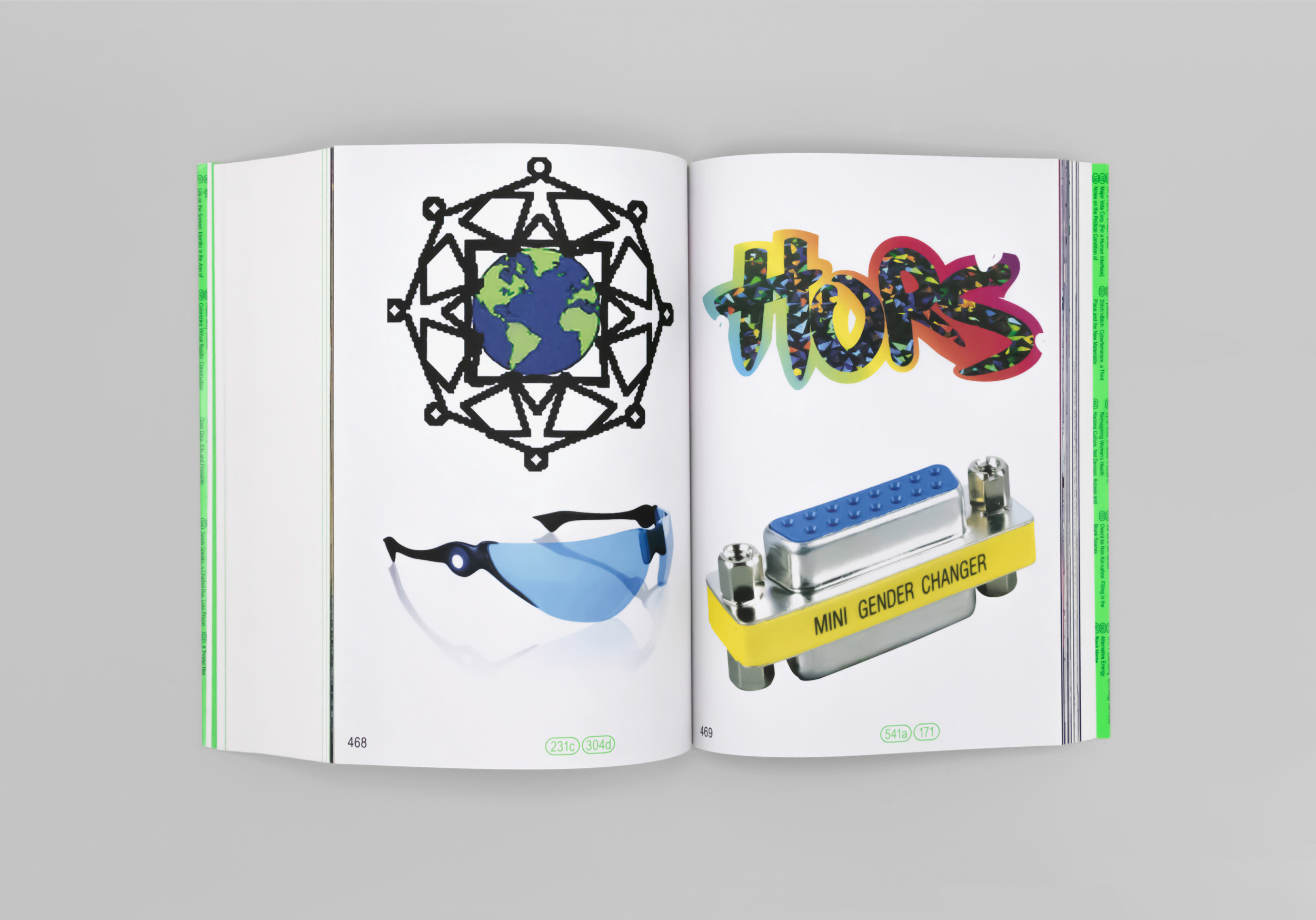

We don’t want the book to feel precious. The pages are soft and the book is fluffy, inspired by the New Woman’s Survival Catalog, the Whole Earth Catalog, the phone book, and the McMaster-Carr catalog. It feels lived-in and used.

“It really starts to feel like this polyvocal, cacophonous, multi-authored reading experience. That was, for me, the most important: How can we amplify so many different voices?”

Sanjana: I’m curious about the decision to foreground certain entries, or certain movements.

Mindy: While the book was crowdsourced and moderated, perhaps the biggest curatorial move was the selection of pull quotes, cross-references, and full-bleed images. For the rest of this index of indexes, it flows through columns.

For me, it was important to be representative of what was happening in different regions at different times. The cross-references then act as hyperlinks. We wanted to encourage nonlinearity, and allow you to jump throughout the book to entries that are complementary, or that juxtapose with the theme that you’re reading. It really starts to feel like this polyvocal, cacophonous, multi-authored reading experience. That was, for me, the most important: How can we amplify so many different voices?

Sanjana: One of the things I’ve always really liked about the project is that it provides many counter-narratives to internet history, like DARPA and the US military. Why is it still important to have these counter-narratives?

Mindy: When you learn about internet history, we often focus on the grandfathers who created the architecture and protocol, and we forget that grandmothers were part of it, too. The first computers were women—‘computers’ meant ‘people who computed.’ Even more so, we forget that, in the stack, the top layer is the application. So to dismiss the social movements and the aesthetics that have emerged online would be a disservice to this history.

Yes, it’s a counter-narrative, but I don’t think it’s actually marginalized in many ways. The growing sense of techno-dystopia has become mainstream. This book collects concrete moments of this mutation, and how our perspective of the internet has changed. There’s still a lot of work on how technologies can be made grassroots, and how we can make our own tools.