Artificial Intelligence may be new, but its racial and gender-based biases are not—paradoxically disappearing the individual under the guise of championing diversity

Recently, it was announced that Levi’s had hired a Dutch firm to “supplement human models” with AI-generated ones to allow consumers to see themselves represented in their e-commerce experience—a decision that was explicitly meant to advance their goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion. As several journalists observed, however, the real outcome of this corporate strategy was that Levi’s would not have to pay actual human models who embody the kind of diversity the brand claims to champion.

For Levi’s, the stakes were already high: Only months ago, the company found itself in the news when a pair of vintage jeans went up for auction, featuring an old logo, “The only kind made with White Labor,” which was used after the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—a brutal piece of legislation that especially impacted the community of Chinese laborers in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Levi’s was founded in 1853. There was something particularly discomfiting about this spectral return of exclusionary practices, superficially sanitized through corporately-sanctioned reparative gestures, at the very epicenter of the tech industry.

AI may be new, but as we are increasingly aware, its racial biases are not. Lurking behind seemingly-objective methods of collecting, processing, and analyzing the massive streams of data that feed these dizzyingly complex neural networks is a premise with a deep and disturbing history and media archaeology: the creation of images of non-existent people to serve as a token of a type. In 1993, the image of a woman with a light brown complexion appeared on the cover of a special issue of Time, alongside a heading that, 30 years later, reads like a MAGA fever dream: “The New Face of America: How Immigrants Are Shaping the World’s First Multicultural Society.”

The rendering was created by Kin Wah Lam, an imaging specialist at the magazine, who combined the images of 14 models selected by the assistant picture editor. The magazine claimed that this image, and its accompanying gallery of biracial progeny, was all “in the spirit of fun and entertainment,” and disavowed any scientific objectivity. Yet the very precise percentages given of the fictitious woman’s racial makeup—“15% Anglo Saxon, 17.5% Middle Eastern, 17.5% African, 7.5% Asian, 35% Southern European, and 7.5% Hispanic”—betray the rigidly-fixed racial categories that invisibly structure the superficial appearance of diversity. In the end, the Time cover is less a picture of a person than a colonialist fantasia of US immigration policy, which is to say, of neoliberal empire.

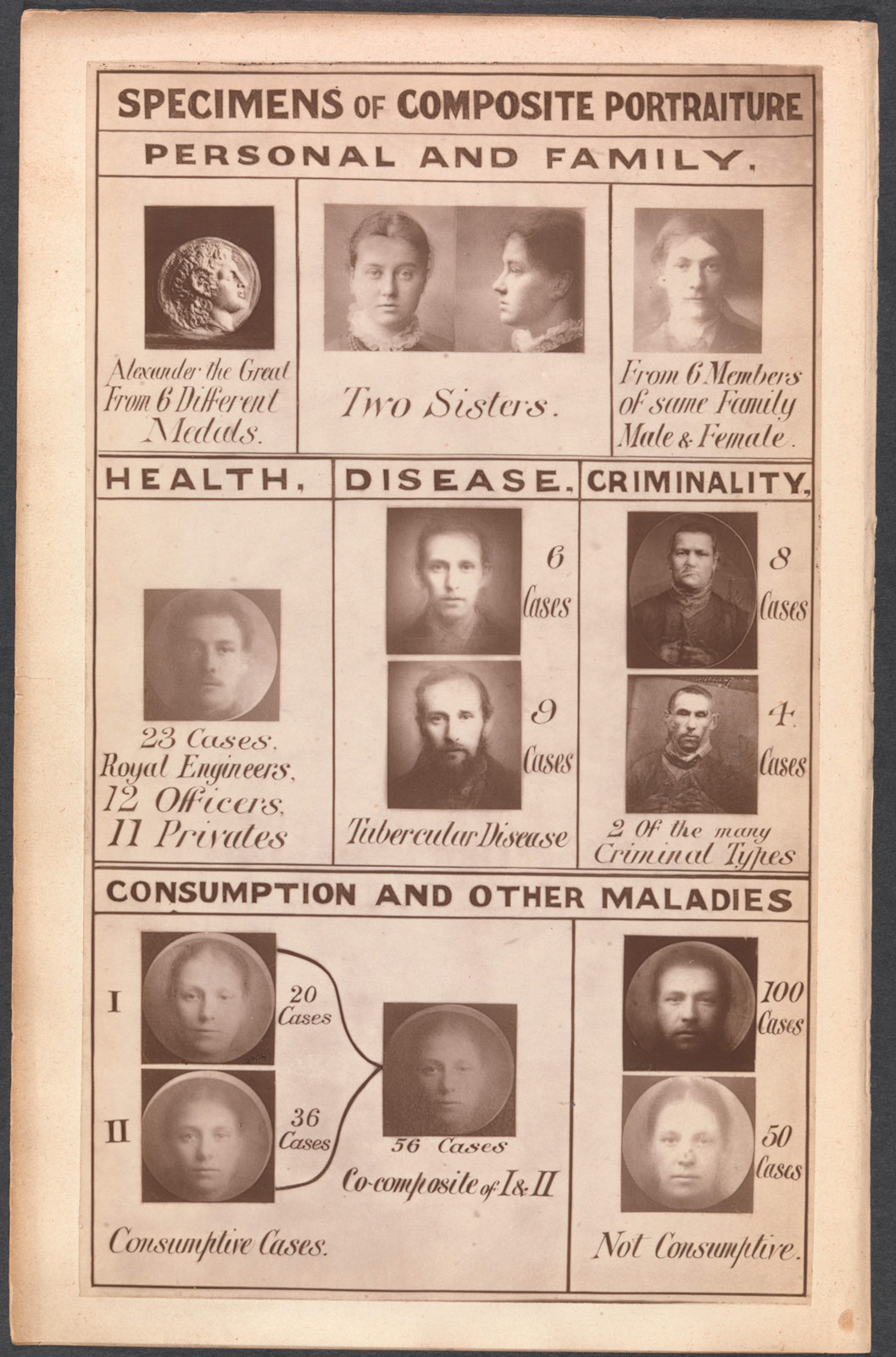

In the 1800s, long before the advent of digital manipulation technology, the English polymath Sir Francis Galton developed a technique for producing composite photographs using multiple exposures—as many as 200—on the same photographic plate. Some of his early experiments seem rather benign, on the surface: Galton made several studies of ancient coins to ascertain the ideal standard of Roman beauty, or the most “accurate” portrait of Alexander the Great or Cleopatra. His method was forensic: By training his camera on the eyes of his subjects, fixed with pinholes that served as register marks like those used in the production of prints, “misregistered” individual features would gradually fade away, leaving a resultant blurry image.

For Galton, an accomplished statistician, the purpose of the composite photograph was to identify the outliers of a given data set to arrive at a pictorial “average.” But the true objective of these studies was hardly numismatic. Rather, Galton applied his methods to the racist and pseudoscientific project of criminology and eugenics—a word he himself coined in 1883—which invented whole categories of people who could be classed and sorted accordingly.

Galton’s experiments can, in turn, be traced back to a foundational story from antiquity: Zeuxis, a Greek artist who set out to paint a picture of Helen of Troy—a woman whose famous beauty not only launched a thousand ships, but also, as it turned out, would test the very limits of art. When he arrived at Croton, a Greek colony in Italy, Zeuxis determined that no single woman was beautiful enough to serve as his model, and so he summoned five, whose different features and body parts could be spliced together to form a composite whole.

The French Neoclassical painter François-André Vincent brought this ancient legend to life, fashioning himself in the figure of Zeuxis, seated before his incomplete painting. Vincent presents us with a metapainting that pictures, as it were, the challenge of picturing itself. As the art historian Elizabeth Mansfield has shown in her study of this legend, and its countless reprisals, the story combines two traditions that would cast a very long shadow in the history of Western art: first, the notion that the imitation of nature requires a certain degree of abstraction or idealization; and second, the naked misogyny of dismembering women’s bodies into scattered assemblages of objectified and fetishized parts.

Within this tradition, a minor yet potent preview of our contemporary moment lies in the critically-panned 2002 film Simone (aka S1M0NE)—a postmodern thesis statement about Y2K aesthetics, released in the historically uncanny valley between 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis. Directed by Andrew Niccol, the writer behind The Truman Show and the writer and director of Gattaca, the demonstrably pre-MeToo plot circles the real and virtual manipulation of women by powerful men in Hollywood. A failing director, played by Al Pacino, stages a comeback by creating a wildly popular virtual actor named Simone by combining the audiovisual inputs of several leading ladies from the silver screen. (One newspaper unintentionally hits the nail on the head, marveling that Simone has “the voice of a young Jane Fonda, the body of Sophia Lauren, the grace of, well, Grace Kelly, and the face of Audrey Hepburn combined with an angel.”) Because everyone believes that this ersatz blonde bombshell is a real woman, Pacino resorts to increasingly outlandish and slapstick stunts to avoid producing her in the flesh. But the biggest stunt of all turns out to have been very real: New Line Cinema’s audacious PR campaign, which went to extraordinary lengths to conceal the identity of Rachel Roberts, the real-life model-turned-actor—and, three months prior to the release date, the spouse of the director—who played Simone, but was not even listed in the credits.

Instead, the studio claimed that Simone was a real fake—a virtual actor conjured up by a real visual effects company in Los Angeles, using the features of the very same actresses Pacino draws on in the film. Conversely, Rachel Roberts was made to appear less real in the film itself. A critic for the New York Times, one of the few who was in on the gag, noted that “Mr. Niccol cleverly makes Simone a slightly ethereal presence by rendering her mouth a bit blurred even as the camera often lingers on it—she’s so exquisite she’s almost out of focus.” It’s a keen observation that perfectly aligns with Galton’s troubling conviction that beauty is best when its distinguishing characteristics are averaged out, and made blurry in the process.

Over 20 years later—even though it was largely forgotten, almost as soon as it was released—Simone is still worth thinking about. Its gimmicky marketing strategy, perhaps even more than its digital manipulation technology, emerged as a telling indication of where things were headed. Dr. Amy Gershkoff Bolles, global head of digital and emerging technology strategy at Levi Strauss & Co., hardly assuaged these concerns when she released a statement that “AI will likely never fully replace human models for us.” The “likely” speaks volumes here: AI models are clearly the future of e-commerce, even as the future of AI itself is increasingly scrutinized.

While the Levi’s strategy and the Simone ploy share a common desire to replace or disappear the human—devaluing labor power across fetishized categories of race and gender—the former differs in its paradoxical claim to presence the human ever more perfectly through the metaphor of reflection, inviting consumers to see themselves represented in models. The context of e-commerce seems important here, and categorically distinct from the more general representational politics of diversity in fashion campaigns, since it is the job of marketing departments to fashion our identities. In the end, what makes the Levi’s announcement so concerning is the way it surfaces a hidden tension between the general and the particular: the company’s promise of diversity, refracted through limitless individuality, that is itself grounded in AI’s basis in the insidious project of human-averaging.