Following the opening of ‘The Close of the Day,’ the artist joins Document to discuss the American South, code switching, and how his biracial experience is far from monolithic

Don’t attempt to put Chase Hall in a box. Born in Minnesota to a white mother and a Black father, the artist—who, as a child, moved around the world with his single mother—found himself straddled between two worlds as a young, biracial man. He discovered every facet of his identity in the process. Hall strips away conventional ideas of race in his work, while emphasizing the nuance of his own experience.

Materiality is an important part of Hall’s practice. He discovered that coffee could be used as a pigment in his artwork while working at the local Starbucks in high school. He salvaged cotton canvas, paint, and stretcher bars that were discarded at NYU, repurposing them for his own work. What originated from necessity evolved into materials that make a powerful statement: Both coffee and cotton were crops harvested by African slaves.

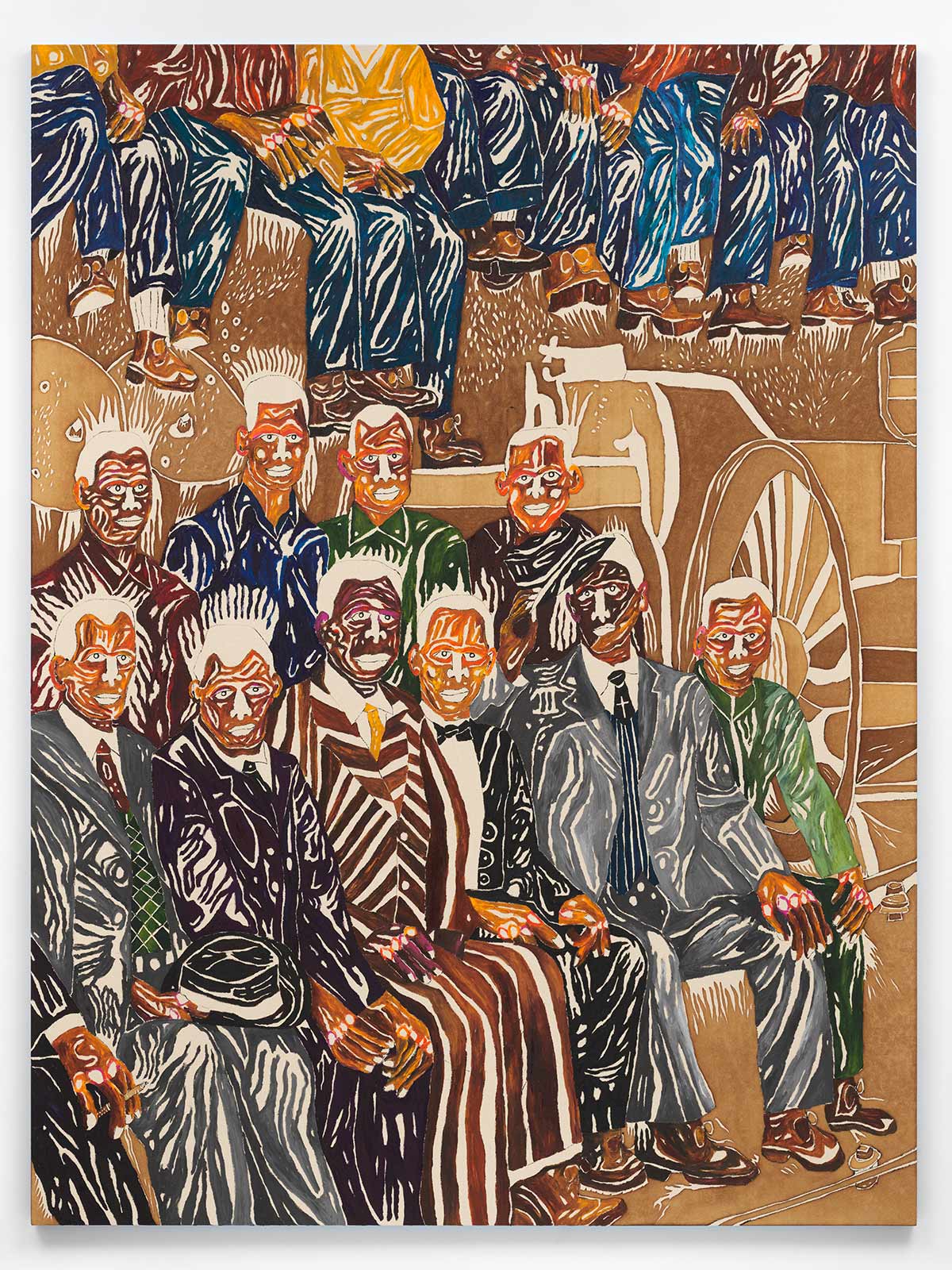

The Close of the Day—Hall’s first solo museum show, on view through August 21 at the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Museum of Art (SCAD MOA)—features nearly two dozen new paintings. The artist mined his memory, creating portraits of characters closely related to him (the exhibition opens with a self-portrait), as well as those he’s observed in the everyday (a group of cooks in the kitchen) and legends he’s long admired (Thelonius Monk). Hall embeds a coded language into his work—an S for his mom Suzanne, LNC for Lauren (his wife) and Chase—to pay homage to his loved ones. The Brown faces depicted across the exhibition, injected with swaths of white space, range from introspective to joyful—offering a nuanced display of non-white life, a subject that’s been often neglected in art history until the last half-century.

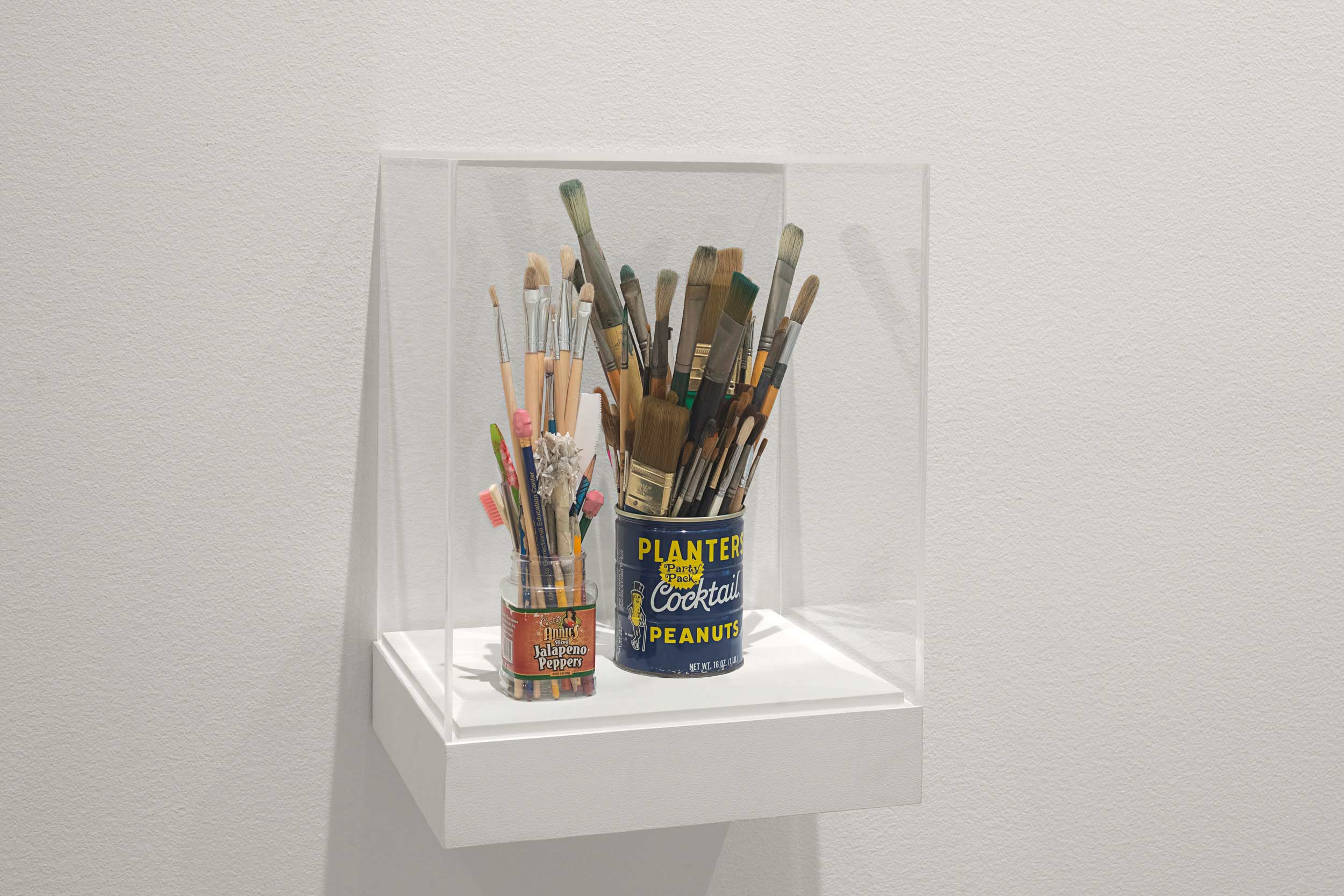

Hall’s exhibition opens with a readymade of sorts: a jar of his father’s paint brushes next to a can of them owned by Jacob Lawrence—an artist Hall admires—encased in a transparent box. Each painting is displayed alongside a response to the work from local community members. “My first observation of the painting caused me to reminisce about the 1950s and 1960s when Blacks were not allowed to compete against white teams in the city of Savannah,” reads a quote from former high school football player Willie DeLoach, next to the painting Huddle (Red, White and Blue), which depicts a team of Brown football players. Installed in one room lined with Savannah Gray Brick—which enslaved people made by hand at the Hermitage, a Savannah plantation—is an enormous Wurlitzer organ, standing before two rows of church pews as a space for contemplation.

Document sat down with Hall to discuss Savannah, code switching, and why his biracial experience is far from monolithic.

Ann Binlot: What are your impressions of Savannah?

Chase Hall: Savannah, so far, has been an incredibly charged place—from the museum being one of the first railroad stations to the first port in America being [there]. [I’m] thinking about the history of African Americans, and the Savannah Gray Brick, and this relationship to the railroad station—what does that mean for income and commodities and things like that? I’ve been [questioning] the themes and symbols of Savannah: the monuments, the language they use, as well as these live oak trees and the hanging moss. And then meeting community members and engaging with the work, I realized a lot of those notions that I brought here actually needed to be peeled back and reconsidered.

Ann: Most of the works have quotes from local community members, responding to the paintings. It was interesting to read their responses.

Chase: I actually really loved it. That was a profound feeling that I didn’t expect at all; I didn’t even understand what it would mean. During the install, to still be getting testimonials back and seeing them up with the paintings, was—if not my favorite part—one of the [biggest] highlights of the experience so far.

Ann: Your father is an artist. How did that inform your practice and your decision to become an artist? What did you learn from him?

Chase: I grew up an only child, and had a single mom. Me and my father had always been in contact, but I didn’t understand how much of artistic lineage I had until I was older. I had seen some drawings and paintings he did that my grandma had. He was more of a Sunday painter, due to the realities of life. To start the show with his paint brushes next to Jacob Lawrence’s was like a carrot in front of the horse. In a way, it’s something that motivates you to try your best, and [to never lose] track of what the anchor is for you. Dr. Walter Evans loaned us those brushes, and to see them come alive in this kind of Hans Haacke-esque condensation box, in this kind of imaginary studio visit, was my favorite part of install—aside from hearing the Wurlitzer start up.

Ann: What was your father’s work like?

“As we get closer to the future, and we talk about equity, and we talk about rights, it’s important for me to navigate in a way that’s honest to myself—even in that core, even in that genetic humility.”

Chase: It was never a job for him. It was always more technical drawings, and things like that. We’re working together to figure out what it can be in the lens of art. It’s technically more sophisticated, and it’s interesting how we have dialogue now through art, questioning society and identity and all these things I’ve been able to understand—redlining, gerrymandering, premature Black death, alcoholism—that had actually been something to account for outside of your father not being there for you. I think, through the complexities of art, I’ve allowed myself to heal and grieve, but also to make space for new relationships.

Ann: Identity is a big part of your work, and you’re biracial. What was it like, straddling your white and Black identities?

Chase: I moved through Minnesota, Chicago, Las Vegas, Colorado, Dubai, Los Angeles, and New York in the first 20 years of my life. That nomadic experience—

Ann: Why were you so nomadic?

Chase: My mom was a hustler, taking jobs [where] needed to keep a roof over my head and food in the fridge. I never lost sight of Minnesota as an origin space for me and my family. But me and my mom had always moved. [I was] one of the light-skinned—quote-unquote, ‘whitewashed’—kids in St. Paul or Southside Chicago or Vegas, and then the tokenized Black kid in West LA.

Those juxtapositions would put me in the position to understand my own identity, through that lens. Then I started to question my own experience through masculinity, fatherhood, Blackness. I was finding it in these ways that weren’t actually as helpful as I thought they were: Blaxploitation films or cartoons, or rap music. I started developing, filling that void a little bit. Then I started to comprehend deeper and more thoughtfully: Who are other people that show me what Blackness is, outside of dancing and basketball? It’s a question that I’m still unpacking, but I think about Barack Obama or Bob Marley or Malcolm X or Alicia Keys. And, you know, there’s many Black people that are also half-white. When we don’t articulate how non-monolithic Blackness is, all we end up doing is saying, You’re not white, in that three-fifths, one-drop rule [kind of way]. It’s incredibly hurtful.

I think that the best-case scenario is like, What does it mean to be proof of interracial love, in terms of having a child? What does it mean to discredit your own genealogy, to just hope that your whiteness card is never pulled? As we get closer to the future, and we talk about equity, and we talk about rights, it’s important for me to navigate in a way that’s honest to myself—even in that core, even in that genetic humility. But it is an attempt at space for mixedness, as we move further into a world where that’s more and more common.

Ann: Growing up, you moved around so much. How did that affect you as you came of age and started your career?

Chase: Moving around a lot allows you to navigate the American landscape, and I think that’s still what I’m doing in my work. I became aware of how different worlds operate—humanity, assimilation, safety tactics. In Chicago, Vegas, and Minnesota, it’s all football or basketball. And then in Los Angeles, it’s like, if you don’t skate or surf, you’re gonna have a problem. I was able to have my eyes and ears to the wall, and be a sponge. In my practice, it’s almost like wringing that sponge out. And it’s like, What’s in that drip?

Ann: Did you have to code switch a lot?

Chase: Totally. That’s a big part of understanding identities in general, through the lens of the polarizing brackets we’re used to in America. The code switch becomes very pronounced. But when we make room for nuance, that code switch doesn’t sound as violent as it does in the context of not being yourself. Code switching is more just understanding that, like, I love surfing, I love tennis, I love things that aren’t necessarily white or Black. The more [you’re just] yourself, the more authenticity you can bring.

Ann: Materiality is a huge part of your practice. Have you been experimenting with anything outside of coffee and cotton?

Chase: Yeah, there’s been some exciting experimentation with fruits and vegetables that have been breaking down into pigments. [I’m] thinking about ways I can create more of a relationship to this kind of agrarian experimentation, culinary experimentation, and quotidian necessity to engage the world, and not just the elite, painterly crowd. I was making paintings with coffee because I couldn’t afford paint. I was using cotton canvas because—when NYU was throwing out stretcher bars—I was able to turn those paintings inside out. A lot of it started from necessity, and not making excuses about when and how and where I should express myself. I want to continue to use everyday materials, and to think about decentralizing this Eurocentric canonical history.

Ann: The church pews—you said you sourced them from the South, but where exactly did you get them from? Also, tell me more about the Wurlitzer.

Chase: We sourced those from a Black church in North Carolina. They were actually built in 1888. The Wurlitzer was built on July 7, 1923, so we’ll be celebrating its 100-year birthday this year. By architecting, building that brick wall, we’re creating a safe space—a calm space for rescuing, conversation, and also ideation. The brick work in that room was in relationship to the Savannah Gray Brick that I mentioned earlier, where it was history and the future staring right at each other, but also acting as protection.

“I was able to have my eyes and ears to the wall, and be a sponge. In my practice, it’s almost like wringing that sponge out. And it’s like, What’s in that drip?”

Ann: Did you use the church as that space for yourself?

Chase: I found out that both my grandparents worked in the church, for my whole life. I didn’t grow up religious because my mom wasn’t religious, but it was always in my mind’s eye. [I remember] playing Pokémon at four years old on a Gameboy in the pew—like, Okay, you know these spaces. I remember hearing church choirs. I remember the brick.

Ann: Tell me about your use of negative space.

Chase: It stemmed from really trying to understand the breakdown in minimalism. I was looking a lot at Clyfford Still, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and trying to understand the audacity of when and when not to use paint. I was thinking a lot about Lucio Fontana, as well. I was like, If I was so struck by someone cutting through a canvas, what does it mean to leave some of this cotton canvas exposed?

Ann: What was the biggest challenge of the show?

Chase: Sometimes, the challenge [is] making sure that what you care about in your work is shared publicly. There’s bravery in that; there’s courage in that. There’s also worry in that. So the challenge is understanding what boundaries I have to set between my heart and spirit and the world, and what kind of conduit I can continue to have in my practice.

Ann: What’s next for you?

Chase: I’m working on a show with David Kordansky Gallery in September in New York. I’ve been working through, and just trying to expand and create more thorough storylines and deeper relationships to life, and continuing to push the paint coming off the brush.