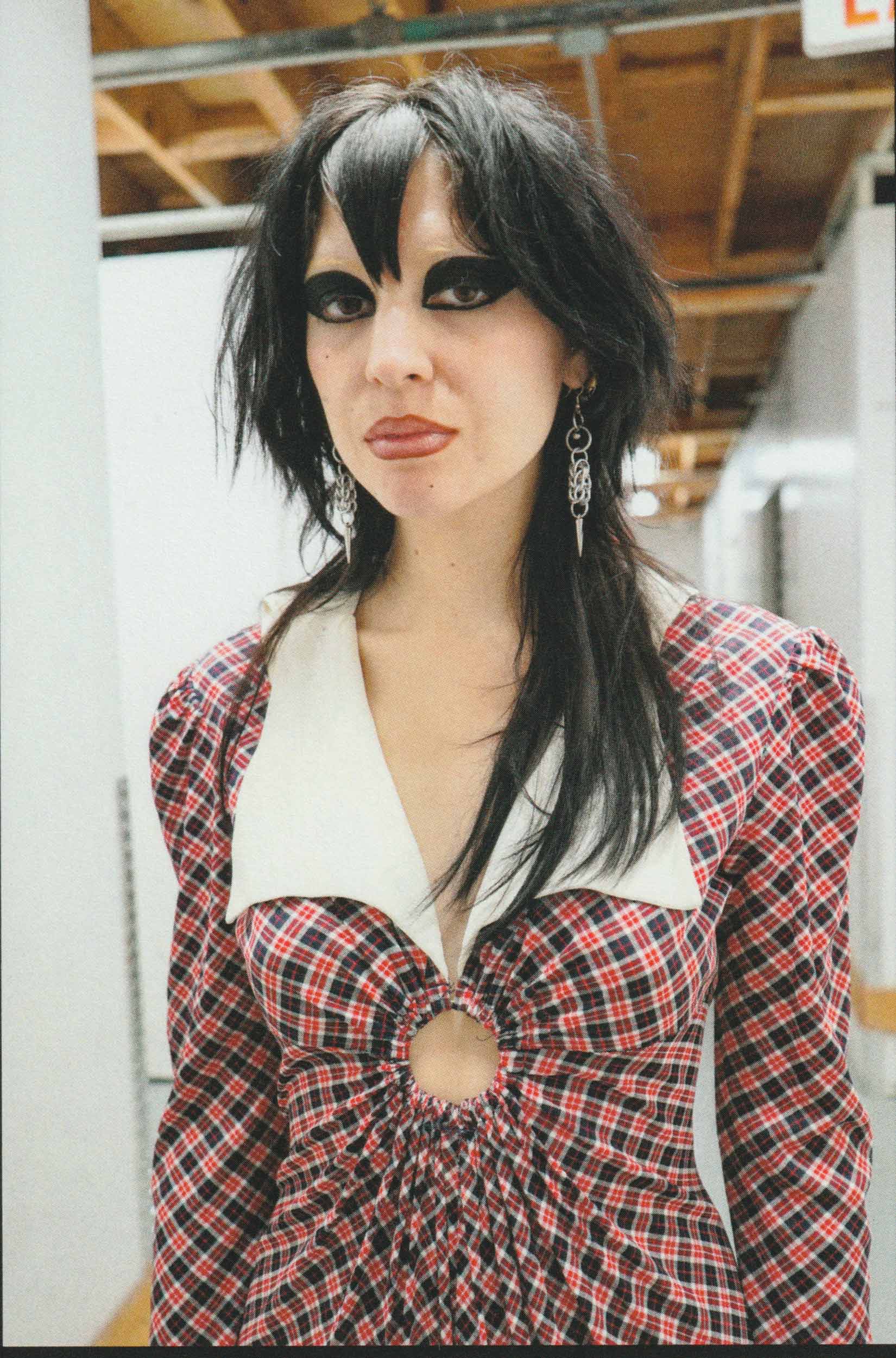

Upon the release of ‘TODO O NADA, VOL. 1,’ the LA-based songstress speaks on how she transforms chaos into catharsis

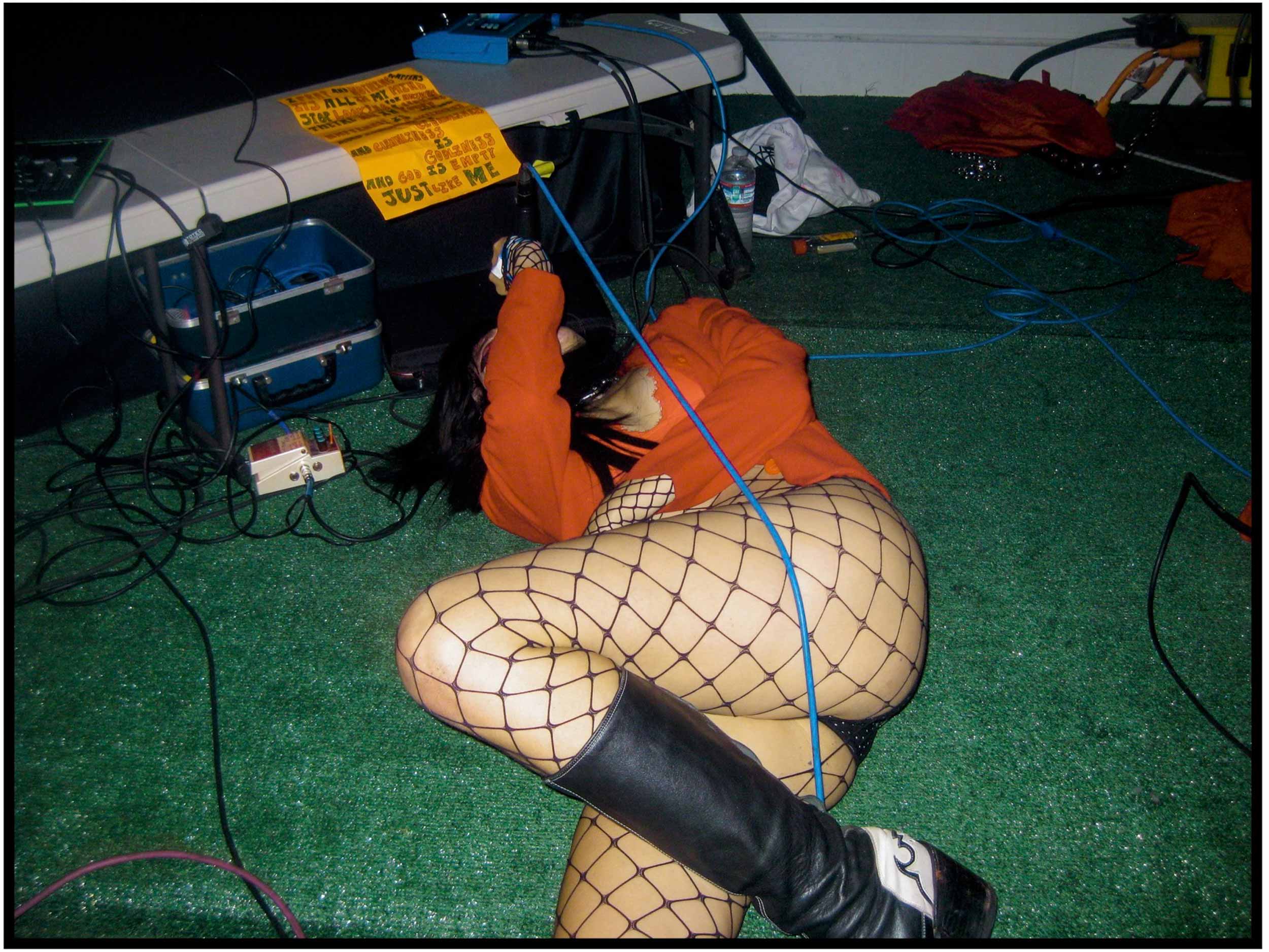

“I can’t do strategy,” musician Tania Ordoñez—otherwise known as Soltera—tells me. It’s nearly impossible to believe; I knew about Soltera well before I met Ordoñez. If you live in Los Angeles and like dance music, you’ve either seen her play, or you’ve heard someone excitedly recount the times they have. Her performances border on unhinged: She’ll ask a fan for their drink mid-song; I’ve watched her, in between tracks, enlist her DJ to help her out of a skirt that was too tight, performing the rest of the set in fishnets; and in November, she facilitated a marriage proposal on-stage. I always thought her ‘no strategy’ thing was the strategy—so I say so. She laughs. “I’m not really into hustling like that!”

It’s a funny sentiment, coming from an artist who spent the last year playing non-stop shows. TODO O NADA, VOL. 1, which is entirely self-produced, is the manifestation of Ordoñez’s break from performing. She built this EP from her living room in the last few months of 2022. It’s an eclectic record, incorporating the raw energy of punk and synth sounds that border on eerie, with the racing beats of ’90s techno. Hard-hitting dance rhythms morph into dark basslines, paired with lyrics that act as mantras on the body’s limits, drunk girls, and social ills.

Nothing in the world of Soltera stands alone. When Ordoñez speaks about this EP, it’s in relation to its predecessor, SIN COMPROMISO—her first body of work, which she released at the end of 2021. TODO is more confident. Ordoñez’s evolving dexterity as a producer allows for more experimentation: “It’s the fastest music I’ve ever made—one track is 160 beats per minute.” This is so fast, it might be considered outlandish among industry professionals. On Ordoñez’s last EP, no track went above 135.

The artist credits her fast-paced sensibilities to her slow-paced upbringing. Raised in Granada Hills, in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley, she spent most of her time walking the three or four miles to Petit Park or to Kennedy—a high school down the street that she didn’t attend, but that all her friends did.

On the Northside, Granada Hills borders Northridge, where the houses become much larger, and a friend of a friend might have a swimming pool. On the east is Pacoima, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the Valley. Until the late-’60s, Pacoima didn’t have curbs or paved roads. This negligence from the city derived from the racist redlining practices of the not-so-distant past, making it necessary for residents to actualize their own paths toward education, safety, and resistance. And just like that, a punk counterculture was born, which would permeate the rest of the Northeast Valley.

Settled between two worlds—one with too much money, and no idea what to do with it, and another that a 1966 LA county report referred to as “undignified”—Granada Hills was the perfect landscape for a young person to invent themself in. When Ordoñez was a teenager, the Valley was home to some of the country’s most iconic hardcore venues, with bands skipping inner-city LA tour dates to play at the Arabic restaurant that doubled as a punk club, just 40 minutes north. While everyone around her was loyal to that scene, she was listening to Radiohead’s Kid A on repeat, and getting into powerviolence—a genre that’s characterized by fast, spastic tempo changes, often followed by slower breakdowns. Listening to TODO, this temperament is present in nearly every track.

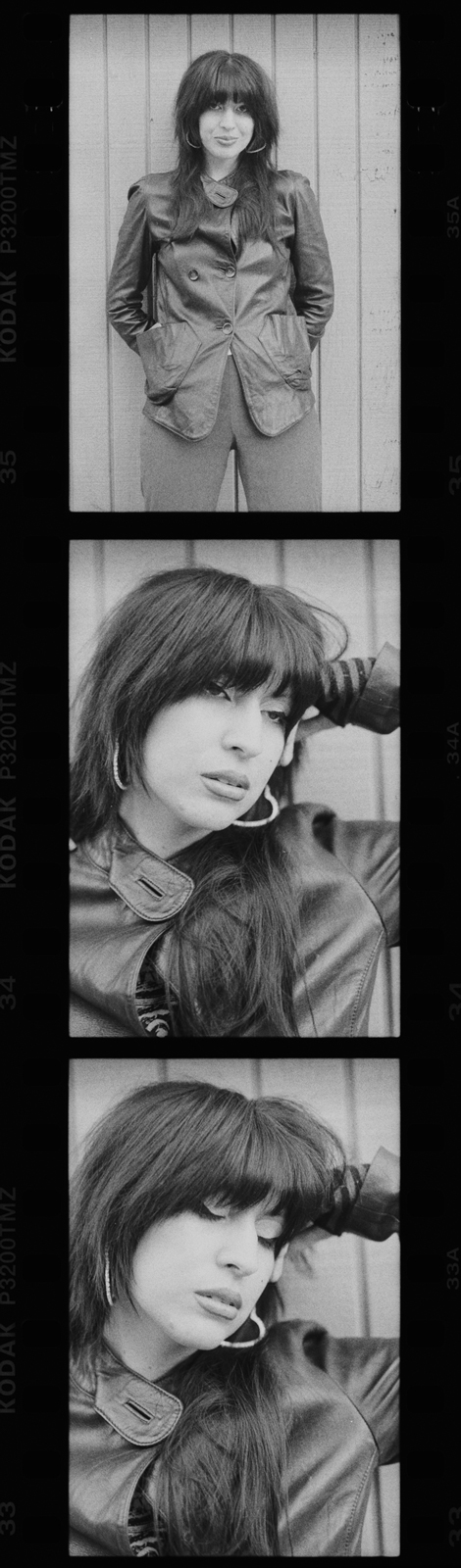

“In the valley, there were actual punks,” Odoñez says. “They had liberty spikes, they were broke, they only had one outfit that they’d wear every day.” But not long after 2011, when the last real punks of the San Fernando Valley graduated high school, all those hardcore venues began to shut down. Following suit, Ordoñez did what a surprising amount of kids from the Valley don’t do: She moved to the city, landing first in Boyle Heights, then Echo Park, where she became Soltera.

The name Soltera comes from the term that refers to widowed and divorced women in Columbia, Ordoñez’s home country. Formally defined as “without a man,” it’s a radical status to hold. “It’s a big deal for Latin women to leave their men—it just doesn’t happen. Meeting a single woman means something. It’s a commitment to being autonomous. It’s rare” she explains. The artist speaks about her mom, who found herself relearning how to navigate her social ecosystem following the passing of her husband, Ordoñez’s father, in 2015. The term was once derogatory—and to many, it might still be. It’s clear that, to the artist, there’s pride in being a soltera. Her mother was offered a new life, new peers and a new identity following their shared loss—and Ordoñez’s musical project was born.

““People tell me all the time that my shows are chaotic—that they’re cathartic. When I’m onstage, nothing else exists.”

“Losing a parent is surreal. Every day I felt like a ghost, I needed to be alone. I couldn’t speak, I didn’t want to try to speak.” The artist bought her first synth at Perfect Circuit, just down the road from Sherman Oaks Castle Park—the Valley’s beloved mini golf course. Three years later, she would host a screening of her music videos there, where a group of teenagers from Pacoima would wait to ask her for a photo while security made their closing rounds. That synth provided respite, offering a sonic landscape for Ordoñez to release not only the grief of losing a parent, but also that of navigating loss as a woman in an ever-increasingly conservative, heavily-policed Los Angeles.

Though growing up, Ordoñez was active in the music scene, attending shows and watching as her friends joined bands one by one, she was never encouraged to participate musically. Now, watching her skills as a producer advance has been a tangible mile marker for her—a way for her to monitor her own growth, as an artist and a person. “I just started dropping tracks [online],” she says. “I didn’t even think about it. There was no anxiety about how it might be received. Because I couldn’t see anyone who was listening, it felt free. I needed a place to let it all go.” What Ordoñez couldn’t speak in her daily life, Soltera was screaming—and though the artist’s audience seemed anonymous at first, they made themselves known at her shows. Watching Ordoñez perform in front of a room full of first-generation queers and Valley kids, it’s clear that her mantras—nearly entirely shouted in Spanish—are resonating.

When I ask the artist to walk me through her process, she leaves the room mid-sentence and returns with a notebook. Positioning herself on the ground beside me, she opens to a blank page and draws 16 rectangles, filling them in by fours: “This is what makes a techno beat.” She leaves the room again. “I’ll grab my laptop so I can show you on Ableton, it might be easier to understand. You can make a beat that way, too.” Ordoñez is completely, earnestly impressed with her own ability to make sound—and unlike her early male counterparts, she wants to share that magic. This willingness to learn publicly is relatable. Soltera may be Ordoñez’s alter ego, but she’s just as much a mirror to her audience members.

At the moment, Ordoñez is enjoying the practice of presence: “People tell me all the time that my shows are chaotic—that they’re cathartic. When I’m onstage, nothing else exists. Soltera is spontaneous. When I step offstage, I become Tania again, instantly.” While Soltera requires a crowd, Tania seeks out quiet. Where Soltera is demanding, Tania is patient. And though she doesn’t believe in celebrity, and doesn’t count popularity among the things she values, the breadth of her influence continues to grow—so much so that a certain film company, behind some of the most iconic releases of the last 10 years, is in talks to slate her in a feature film still in pre-production. “Who knows if it’ll happen. I’ll probably do it,” she shrugs, lifting the left ear of her dog Tapatío. “It’d be cool, I think.”

You can listen to TODO O NADA, VOL. 1 here.