Years following the success of ‘Take Me Apart,’ the artist fills Document in on the long road to ‘Raven,’ her much-anticipated sophomore album

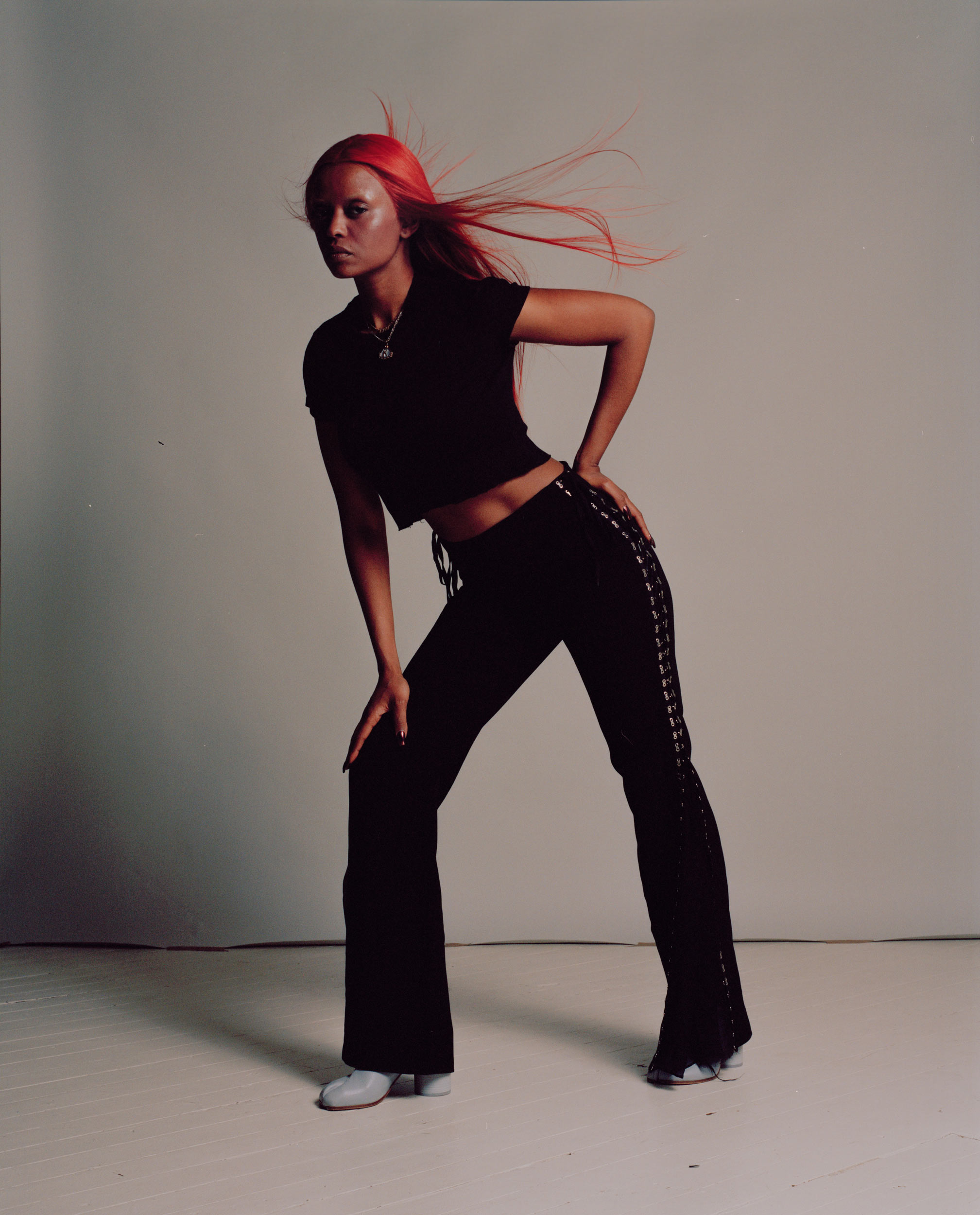

At the photo shoot that would go on to accompany this interview, Kelela arrives on set with a hot new wig and a crystal-clear artistic vision. She acts as de facto creative director, with an astute awareness of how best to highlight the metal-clasp details on her vintage Jean Paul Gaultier pants. “Try it from over there,” she directs the photographer. “That’ll really capture the look.” She’s absolutely right.

As tender as she is magisterial, Kelela’s assuredness isn’t that of a diva. Rather, it’s the conviction of a musician who has taken her time to carefully refine her sensibilities, which shines through on her long-awaited sophomore album, Raven.

Following the release of 2017’s Take Me Apart, Kelela didn’t churn out more music to meet the demand of her cult following. “I didn’t want this record to feel like Take Me Apart part two—which is, frankly, something we see a lot in the music space,” she says. So, she took her time. She danced, she loved, and—through it all—she wrote. And what she wrote is revelatory. While Take Me Apart documented a search for security in the face of love’s uncertainty, Kelela’s new record finds the artist fully-formed in a security of her own design, and brave enough to claim what her heart desires.

Throughout Raven, Kelela sings about a lover who is “far away”—sometimes melting away, sometimes floating away, sometimes running away, but always estranged. On songs like “Happy Ending,” “Let It Go,” “On the Run,” and “Enough for Love,” the artist tries hard to convince her lover that their relationship could be beautiful, if only he’d be brave enough to submit to intimacy. She asks her paramour where he goes to hide. Just “let it go,” she insists on one track. It could be a “happy ending after all,” she posits on another.

The theme is so consistent, you might imagine all the songs speak to one relationship. But Kelela says that the situation is simply one she’s come up against repeatedly. “I was talking to somebody this past fall, and the [same] dynamic manifested itself,” she recalls. “I was like, ‘You’re gonna think these songs that I wrote two years ago are about you.’ That’s how patterned this behavior is.”

On the whole, Raven is a memorandum on distance: Kelela yearns to close the gap between herself and her partners, and likewise, seeks to create healthy space between herself and the toxic systems around her. She knows that, in order to be vulnerable, you have to feel safe. Some boundaries need to be set for others to be broken down.

While thematically centered around intimacy, Raven is also a love letter to dance music. Across the album, Kelela purposefully utilized elements of various electronic subgenres, like drum and bass and house. It’s no mistake, she confirms, that the album’s name is a pun for “raving.” She’s reclaiming the valor of the Black femme, situating herself at the center of the dance floor and at the helm of the DJ booth in turn.

Kelela is now gearing up for her RAVE:N tour, through which she intends to craft an experience that falls somewhere between a club set and a serenade. In the last few years, many have wondered where she’s been. But if we’re to learn anything from her evolution, it’s that we should wonder instead about where she’s headed to next.

Ludwig Hurtado: Do you feel that people have misconceptions about how you spent your time away?

Kelela: In this day and age, when you decide to not be on the internet, it’s literally like you die. It’s as if you chose to take yourself out or something. The reality is that I just didn’t want to post on the internet. I’d finished the record in terms of songwriting. I pretty much had it done in early 2020, in terms of how I thought it was going to sound. I thought it was going to come out later that year. Honestly, the shit just took a lot longer than I thought it was gonna take. I was very eager for it to come out.

In 2019, I didn’t know where I wanted to go with the next record. I still had hella tracks in my pocket, and I could have been feeding this capitalist framework of just releasing music consistently, rather than it being about the arc that I’m creating. For me, I care more about the arc. I like it when I can hear the growth in an artist from one record to the next. To be honest, I didn’t want this record to feel like Take Me Apart part two—which is, frankly, something we see a lot in the music space.

Ludwig: It seems very brave to me. I think about this with artists like Frank Ocean or Rihanna: The stakes can get so high that the expectations from the public become impossible to meet. Were you afraid of developing too much hype around your second record?

Kelela: Of course. There’s always some sort of external pressure. I’m trying to center the messaging, and then making business sense of what feels aligned with my values. That’s basically my game: I’m trying to see how much business sense I can make out of things that are real for me. Obviously, we’ll always have to compromise. But I don’t think that I need to take every opportunity. Not every opportunity that comes to me is meant for me. Sometimes it looks like it is, and it’s not.

“Not every opportunity that comes to me is meant for me. Sometimes it looks like it is, and it’s not.”

Ludwig: In all of the romantic songs on this record, you write about some hesitation from your lover, and how you want them to be vulnerable with you. I imagine you wrote these songs over the course of a long time. Are they all about one person?

Kelela: They’re not. Male stoicism is a thread that you can draw between a lot of the songs, articulating a romantic dynamic. And yeah, I’m often coming up against a stoicism or emotional stuntedness from men, to be really honest. I think that the reason why it might sound like it could be one person is because that’s just something that exists across the board. If you switch the man, it’s the same dynamic, you know? I was talking to somebody this past fall, and it manifested itself. I was like, ‘You’re gonna think these songs that I wrote two years ago are about you, and I just want you to know that that’s how patterned this behavior is.’

Ludwig: Listening to this record and reading the lyrics, I recognized the motif of distance throughout. But you didn’t intend for that to be the case, and didn’t realize the pattern until after the record was done.

Do you find that writing songs allows you to learn about yourself, kind of in the way one does when they talk to their therapist and realize things they hadn’t been able to verbalize before?

Kelela: Yeah, a hundred percent. I am in a conversation with myself, and I learn about what I’m feeling and thinking. I don’t think of myself as a conceptual artist. Obviously, there’s a lot of conceptual work happening, but I wouldn’t say I’m approaching this record from a place of like, This record is about this, and these are the themes. It’s not giving all that. For me, I am sort of intuitively approaching the instrumental, feeling my way through it, and being like, What does this feel like? It wasn’t until I wrote almost all of the songs that I took a step back. I finished reading the lyrics, and I was like, ‘Oh, my God, do I sound like a beg?’

Ludwig: But you didn’t change the lyrics. You leaned into it.

Kelela: Yeah. I quickly stepped away from that sort of internal criticism, because patriarchy and white supremacy will have you internalizing perfectionism, or thinking that you have impostor syndrome. It’s like, no—imposter syndrome is too pervasive of a feeling for it to be something individual. It’s very much a response to systems operating on all of us.

Ludwig: It seems like, on all the tracks, you’re confronting white patriarchy in one way or another.

Kelela: Yeah. As a queer Black femme who wants to lead with vulnerability and tenderness—if you’re dealing with people who inherently have more privilege than you—you’re going to end up in very similar dynamics. And that’s the emotional identity of the record. Raven is definitely for the people who are wearing their hearts on their sleeves in the face of privilege, and a hardened numbness that comes as a result of literally not having to do emotional labor.

Ludwig: This record seems to really be about distance. Sometimes, you’re coming up against men who feel too far from you. At the same time, though, you’re actively choosing to distance yourself from certain types of toxicity.

Kelela: Definitely, yeah. On the one hand, it’s wanting to exist vulnerably and comfortably in this world, and forging that place for me and other people who feel similarly. The other side of that is, you know, I’ve always led with a certain amount of vulnerability and tenderness. It’s embedded in my work from the beginning.

What’s different about Raven is that it’s that ethic with the addition of boundaries—staying soft in this world that is treating me like shit in so many different ways. And I would say that I’m able to stay soft by having strong boundaries. For the songs where it’s not overtly romantic, it’s more about me and my place in the world. It’s the boundary-drawing that happens in those songs, like ‘Raven’ or ‘Fooley’ or ‘Holier.’ It kind of feels omnipresent in that way—that it applies both to me and to people in general. You could apply it to friends, to my career, romantically. ‘Raven’ is the manifesto for that boundary-drawing.

Ludwig: Is that why it became the title track?

Kelela: As soon as I heard that synth in the studio… [my producer] AceMo played it, and I was like, ‘I don’t know what this is, but it’s giving title track!’ I was going to talk my shit on it. I could hear that it was not romantic. So when I went to go write it, I had the lyric, ‘A Phoenix is reborn.’ That’s what I felt the song was about to be about, you know? It’s giving, like, You thought you took me out, but a bitch is back! You thought this had me, but we’re still here.

Ludwig: But the phoenix is sort of ran through as a symbol?

Kelela: Yes. I was just like, It’s too played out. Especially in music. I can’t do that. We always make the white birds good and the black birds bad. So we wanted a black bird, and we literally just started Googling. The title of the record really came from a Google search on the symbolism of different black birds. I’ll read it to you:

‘Because of its black plumage, croaking call, and diet of carrion, the raven is often associated with loss and ill omen.’ This record, it just feels darker, and I think that a lot of people think darker equals sad, or darker equals bad. I think that’s sort of the topical assessment, reflexively. And then it says:

‘Yet, its symbolism is complex. As a talking bird, the raven also represents prophecy and insight.’ I would say I am a translator of emotions. I do think that I translate a sort of interior experience to an external world. I help people connect those two. Facilitating intimacy is a big part of that. So it felt really appropriate.

“Raven is definitely for the people who are wearing their hearts on their sleeves in the face of privilege.”

Ludwig: It’s also a double entendre, right?

Kelela: Yeah. My creative director and very good friend, Mischa, said, ‘Raven, but also ravin’ you know?’ And I was like, Whoah, yes!

Ludwig: Well, I can’t wait for the remix album. It has to go hard.

Kelela: Period! I’m really excited about that, actually, because this record kind of feels like it’s remixes already—if that makes any sense. I’m really pumped for that.

Ludwig: It’s definitely a love letter to dance music. Spanning across so many different genres and weaving them together.

Kelela: I really appreciate that you see it as a love letter to dance music, because one main goal was to move through a lot of the subgenres of dance that have Black origins, and to kind of be like, This is Black, that’s Black, that’s Black, too. [We mixed] them together in a way that felt like DJed. Everything is kind of medleyed together.

Ludwig: When you wrote these songs, you had no idea that they’d be listened to in this current context.

Kelela: Yeah, I wrote the songs before last year’s resurgence of dance music.

Ludwig: Pre-Renaissance.

Kelela: Yeah. Pre-Renaissance, pre-PinkPantheress, pre-Kaytranada’s Grammy moment. There was this thing that I was wanting to articulate, and it might be more apparent now. I think there’s more of a discourse around it because of Beyoncé. But I think, within the dance music space––even though we have more Black people being centered, even though Black people were the origins of these genres—if Black people aren’t winning in the game, then obviously, something’s wrong. The fact of the matter is that an erasure has happened, and it won’t be un-erased until white people are pointing it out.

The record was written from January to April of 2020, so I pretty much wrote all the songs before the uprisings. I remember when they happened, I was like, Wow, I feel like a lot of people are gonna think that I wrote these songs in response to this moment. On this record, I center Black femmes and non-binary people. I want to facilitate a discourse around what’s really happening, from a place that’s not entirely guided by fear—by the fear of losing opportunities and security. I don’t want to lay down to that. I think we need people who are down to say what’s going on.

Photography assistants Nadine Zhan, AJ Kyser. Studio Piece Studio NYC.