In his monthly column for Document, sex writer and activist Alexander Cheves makes the case that cheating is human nature

Cheating is in, baby. Last year, affairs and revenge-infidelity drove the hit second season of The White Lotus, and Netflix got hot in its fourth quarter with Lady Chatterley’s Lover, based on D. H. Lawrence’s 1928 erotic novel about a romance between an aristocrat’s wife and the groundskeeper of her estate. Entertainment was reality, or vice versa. “If there’s one thing celebs did this year,” reporter Ryan Schocket wrote in a year-in-review, “it’s cheat.”

Nothing new here. “When Zeus stepped out on Hera, the Greeks turned his every affair into literal legend,” Aja Romano pointed out last October in a Vox article on celebrity cheating. “When Eddie Fisher stepped out on Debbie Reynolds with Elizabeth Taylor, we turned a messy real-life breakup into a classic love triangle… When Beyonce shaded Jay-Z for cheating on her, we opined that even a woman who seemed so close to perfection had to deal with a trifling husband.”

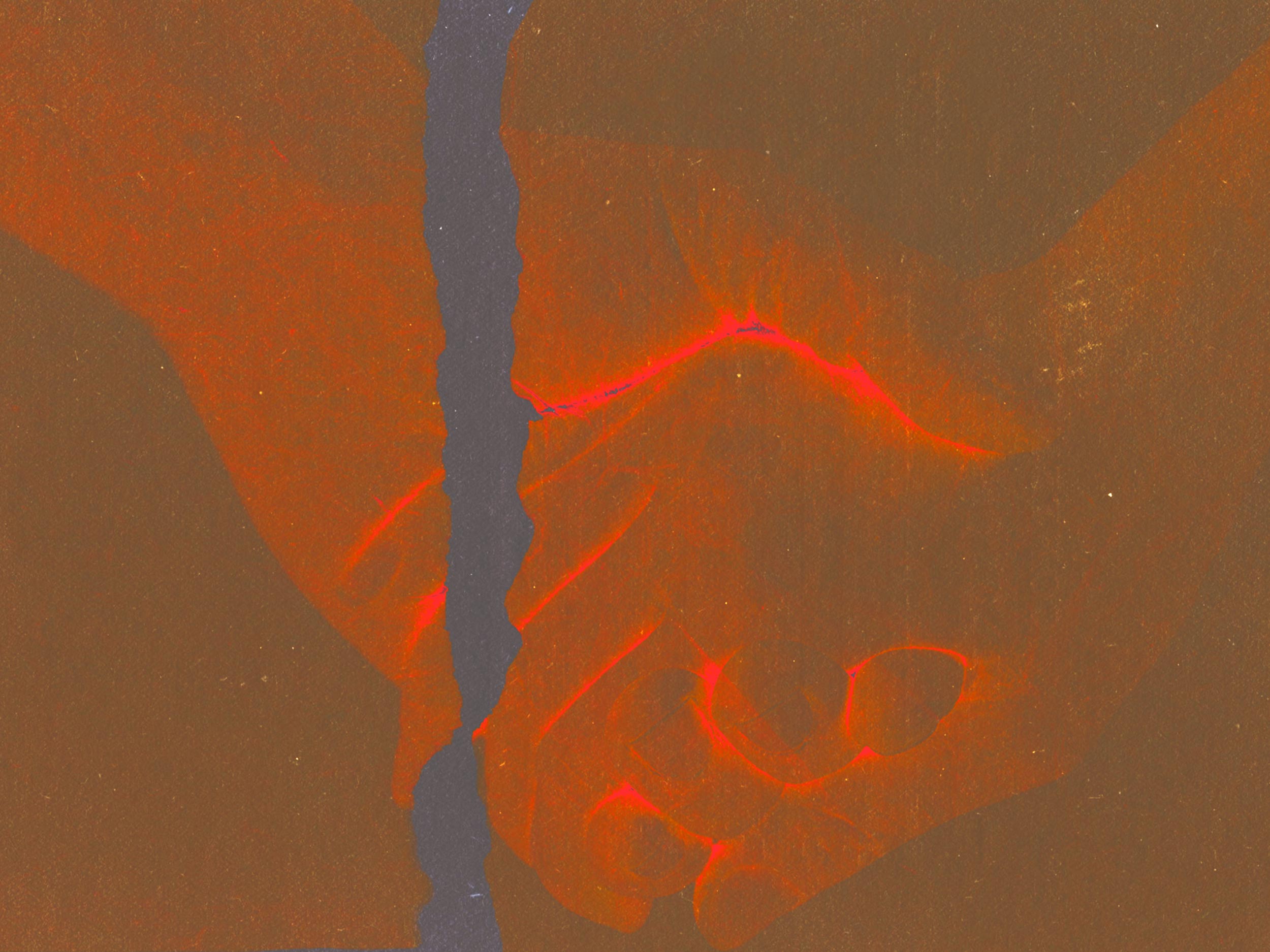

On New Year’s Day, I learned that some close friends of mine, a gay couple, had split. A buddy said in a low voice—one of reverence, the kind people reserve for gossip and cathedrals—that there was “another guy.” People love a cheating story, even when it’s about people they know and love.

Why do these tales entice us? If cheating is a spectacle, it’s a commonplace one. Data exists mostly for married couples, not people casually dating, and largely relies on self-reporting (so numbers should be viewed skeptically), but on average, studies show that one in five wedded folks have a cheating partner. In the media, our culture’s cheating stories tend to involve ugly virgin-whore myths, propping up hackneyed gender tropes about how men and women “naturally” behave. Romano writes: “Cheating scandals say more about the pop cultural narratives we superimpose upon them than they do about the people involved.”

I am a full-throttle, red-blooded cheater. I cheated on everyone I dated until I learned about non-monogamy and polyamory—until I learned of more ethical, honest ways to date and get my sexual needs met. Non-monogamy likely doesn’t need explaining: You know couples, probably queer ones, who permit sex outside of their relationships, usually within certain parameters. I don’t need to explain polyamory, either. The word does it: “poly,” from the Greek polloí, or “many,” and the Latin amor—“love.” Polyamory is loving multiple people and having relationships with them, with the consent of everyone involved. I am non-monogamous and polyamorous.

Progressive relationship therapists and sex writers like me often present these concepts as “solutions” to cheating. These practices get written about as relationship structures in which the fear of cheating is assuaged, the danger of infidelity rendered moot. Non-monogamy and polyamory do not account for the fact that cheating can be fun because it’s cheating—that honesty, though ethical, just dulls the thrill of having an affair. I see these ideas as half-solutions, stepping stones on the way to self-understanding. They are part of our ongoing attempt to make sense of ourselves and the way we love.

“I stopped cheating once cheating no longer existed—once I mandated my freedom to fuck freely.”

The terms “non-monogamous” and “polyamorous” smack of newness and progressiveness, but the relationships they define have always existed—for as long as humans have pair-bonded. In the past, these couples existed mostly covertly and sometimes publicly: They are the couples throughout history who permitted exotic affairs or who simply looked the other way; who made mutual agreements and built bonds on honesty and trust; who led the free-love movement, the Summer of Love, and so on. But if free love never happened, and culture never moved past the ’50s—if I was still expected to be a doting husband to a dutiful wife—I would cheat. I am a natural-born cheater. And, I believe, so are you.

I owe a debt to Dan Savage, the renowned advice columnist behind Savage Love, which is syndicated globally. Savage built his career as the gay, kinky Dear Abby and inspired me to start writing about sex, which I’ve done for a decade now. (I modeled my advice blog Love, Beastly after Savage Love. Dan, please don’t sue me.) I’ve appeared on Savage’s podcast, and I’ve been mentioned in his column. And though we’ve never discussed this, I know he and I differ in our views of monogamy. He thinks it can work for some—that it is one of many possible relationship structures, albeit difficult to sustain. Raised Catholic and now a kinky gay man in a monogamish (his term) marriage, Savage is a thinker whose advice aims to help relationships work—often for the sake of the kids. “Making it work” might mean allowing for some extramarital fun. He sees monogamy as the global standard from which non-monogamous and polyamorous communities diverge, though all are laboring toward the same goal: staying together.

Comparatively, I’m a fatalist. I am faithless, where Savage is a believer. I think that monogamy is unnatural for humans and that the default state of happiness for a person is as a unit of one, with romantic and sexual passersby that come and go in time. In my view, most hiccups in love are signs that a relationship has run its course, not hurdles to overcome. Most of my advice centers on letting it go, not making it work.

Cheating is a social construct that only exists within monogamy, itself a Bronze Age mandate that comes from antiquated religious dogmas and the systematic subjugation of women. In other words, it has no bearing on our natural behavior. Monogamy is observed in some animals but not in us. Like our closest primate relatives, humans are categorically promiscuous. In their seminal book Sex at Dawn, anthropologists Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jetha write: “No group-living nonhuman primate is monogamous, and adultery has been documented in every human culture studied, including those in which fornicators are routinely stoned to death. In light of all of this bloody retribution, it’s hard to see how monogamy comes ‘naturally’ to our species. Why would so many risk their reputations, families, careers—even presidential legacies—for something that runs against human nature? Were monogamy an ancient, evolved trait characteristic of our species, as the standard narrative insists, these ubiquitous transgressions would be infrequent and such horrible enforcement unnecessary. No creature needs to be threatened with death to act in accord with its own nature.”

Ryan and Jetha’s research suggests that humans are happiest with many sexual and romantic partners in tandem—a state some people today call “relationship anarchy.” It’s anarchic, yes, but that’s nature—ours.

“Monogamy is literally the only thing humans attempt where perfection is the only metric of success.”

We, the apes on two feet, like sex—along with lots of juicy, squirmy feelings of love, at least for short whiles. We built community bonds on these feelings, bonds that evolved into the world we have now. Even though feelings of love are often stressful and can lead to violence, they give us an evolutionary advantage: They make us work together, share the hunt, protect the tribe.

I see relationships as temporary experiences, not lifelong ones, best appreciated like a traveling fair: You don’t know how long it will last, so you enjoy it before the lights go off. Relationships are shared time—nothing more or less. It’s natural for people to drift apart, grow at different speeds, crave time with others, and so on. The strongest relationships are flexible enough to allow for this natural wandering. It is a rare but beautiful thing to see two people separate for a few years, date others, live in other places, and find their way back to each other without jealousy or vindictiveness. Queer people in particular have long been at the vanguard of discovering new ways to date. We pioneer diverse relationship structures—like triads, fetish communities, and large polyamorous clusters—and we make them work.

I must defend cheating—not because it’s ethical, but because it’s real. It should not be ignored or relegated to shame or celebrity scandal. Cheating is, in its own way, like non-monogamy or polyamory: It is an inquiry into understanding relationships—an attempt to make sense of ourselves.

If you cheat in 2023: Yes, you fucked up. And you hurt someone, even if they don’t know it yet. But you’re not a horrible person. You fucked up in an unrealistic and unforgiving system that punishes natural behavior. As Dan Savage said recently, “Monogamy is literally the only thing humans attempt where perfection is the only metric of success.” If you cheat, it might be because monogamy doesn’t work for you—and it’s time to seek an alternative.

I found non-monogamy and polyamory because my relationships failed—ruined by my inability to fuck one person at a time. I stopped cheating once cheating no longer existed—once I mandated my freedom to fuck freely. If someone can’t grant me this freedom, they can’t love me. These structures may not be the end goals, but they are an honest effort; they are closer to defining how I truly am and how most people truly are.

The reason why we are so fascinated with cheating stories—why, in 2022, we devoured the affair between Amy Robach and T.J. Holmes, hosts of Good Morning America, and continue to ponder the identity of Beyoncé’s “Becky with the good hair”—is that we are all interested, on some primal level, in sex with someone else, because they’re someone else. You’re not the villain of a TV show or the fuckboy in a pop song: You’re just human, just one of us.