With ‘Surgery Channel,’ the LA-based band dissects both society and the self, offering a rhythm that feels danceable and dissonant at once

If you watch the crowd at any punk show, you’ll find that synchronicity is distinctly lacking. Heads are bobbing in differing directions at varying speeds—somehow all in keeping with the music. It’s simultaneously loose and rigid: arms either stiffly crossed and hands pocketed, or thrusting and thwacking with willing and accidental violence. The dissonance among punk’s audience is a staple of the genre, which limits classifications of flailing limbs to “movement” rather than “dance.”

The C.I.A.’s album Surgery Channel tempts to break that tradition, offering a rhythm that feels distinctly dancey, while maintaining all else that characterizes punk: both unrestrained and self-conscious, its lyrics deeply instilled with emotion in its most volatile forms.

The concept for the band is simple, says frontwoman Denée Segall: “Two basses, a drum machine, and me on vocals.” But The C.I.A.’s sophomore release sees them expand upon the form established in their first—scaling up the production, which consequently allowed for more experimentation, most obviously emerging in the slew of characters produced with Segall’s vast vocal range.

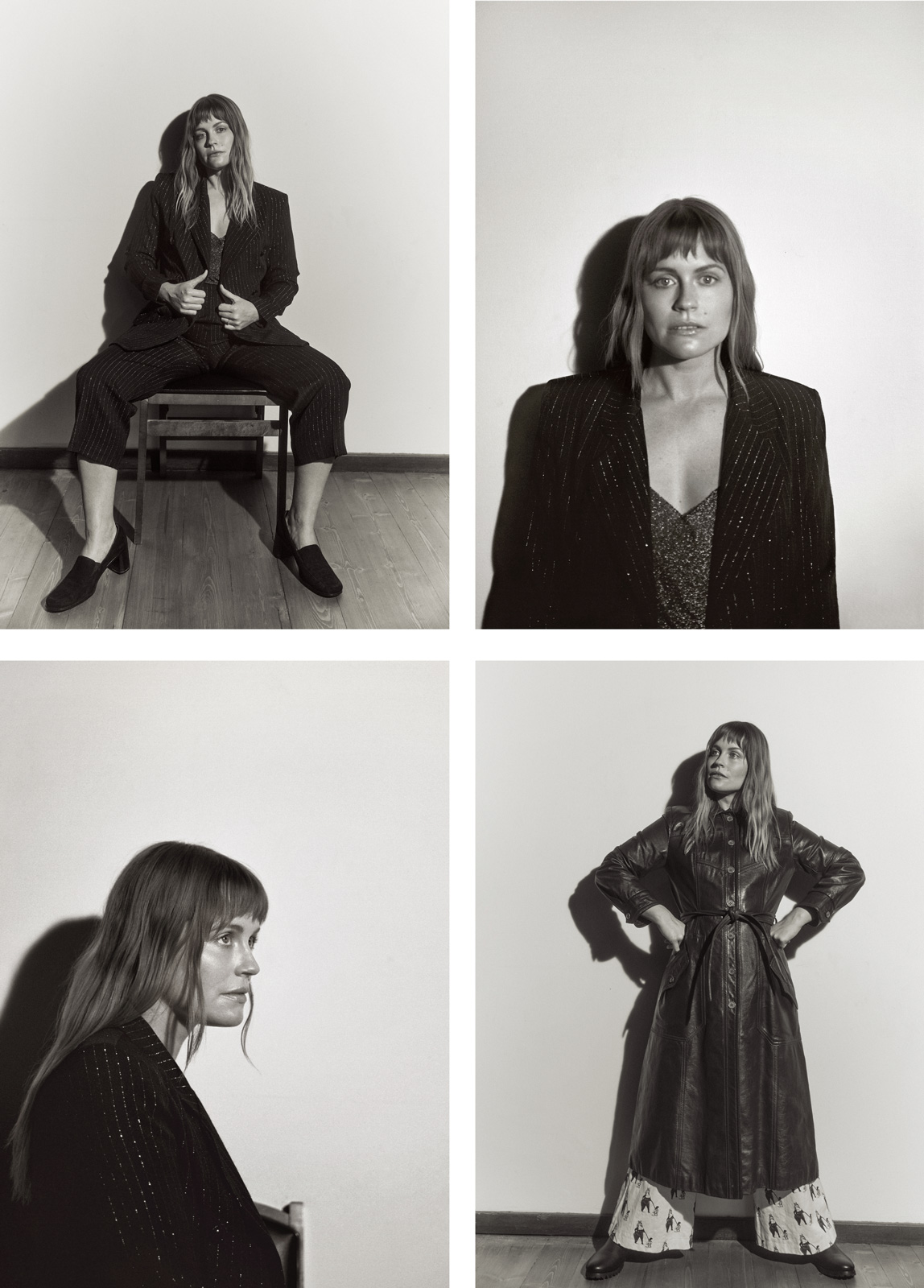

Their self-titled debut saw the vocalist in wigs—the band’s performances at least partially flavored by whatever orange, blue, or two-toned banged bob she selected for the night, backed by her husband, Ty Segall, and Emmett Kelly, both on bass, staring onto the stage’s floor as the drum machine ticked on between them. Now, the wig’s off—in part, an aesthetic cue that this album is starkly different from their last, but also an indication of Segall’s own progression as an artist. “I think I’m getting more comfortable in my skin as a performer and as a writer,” she muses. “Wig off is just, like, a little bit of exposure for me.”

The band’s all decked out in medical dressing now, too. Kelly acquired his nurse’s uniform from a scrub shop near his home in East Los Angeles. Segall acquired Ty’s from a medical site, and her own from eBay—from someone employed at an Arizona state hospital in the ’60s. The album’s name, Surgery Channel, bred everything else on the album: its air of suspense, the sterility in production that’s immediately countered by the dissonant noise of the music itself, newly incorporated synths that resemble the hum of machinery of a hospital, and the lyrical subjects, ranging from actual human dissection to a more metaphorical dissection of the self.

“Wig off is just, like, a little bit of exposure for me.”

Among the best-kept commandments of punk is the redirection of self-contempt or self-consciousness toward hatred of something else—or, more likely, someone else. The essence of the genre is boiling that disgust or disquiet down to its simplest and most emotive form. But sometimes—at its best maybe—punk is introspection: a candid self-portrait of one’s own thoughts, behaviors, and actions. Segall enacts this beautifully, her interrogations of self (“Sick of the way I’ve been giving in / Tight-lipped, frightened, ambivalent”) underpinning her outward critiques (“They’ll take an inch and realign / A little pinch / A little lie / A penny for your skin”).

Surgery Channel is violent, but it’s also compassionate. It’s rhythmic and untamed. It’s growling and whispering, gentle and defiant. It doesn’t follow any particular set of rules—and isn’t that the real point of punk?

Photography by Olivia Malone at Home Agency. Photography Assistant Brook Keegan. Hair by Kelly Peach at Walter Schupfer Management. Makeup by Lilly Pollan.