Ahead of the release of ‘All Above,’ Aimée Portioli expounds upon the evolution of her practice and the art of translating emotion through sound

With music, Aimée Portioli builds immensity. On All Above, the Berlin-based composer, better-known as Grand River, imagines emotion through sound. In the more than two years over which she constructed her latest record, a singular feeling trailed her—one that her sonic vocabulary was better-suited to translate than any verbal language was.

On All Above, the intimacy derived from acoustic instruments and the sublimity of synths intertwine, weaving together an echoing soundscape that is all-consuming of its listener. The record’s cover sees Portioli gazing upward, enveloped in the steam of a waterfall. That feeling of submersion sometimes resembles an embrace, she explains, which serves as the conceptual basis of “Kura,” the opening track of the record’s B-side, premiering today with Document.

“Kura” takes its name from the Icelandic kúra, which means “to snuggle.” Coincidentally, it’s also the name of a river near the Caspian Sea; in this context, its name comes from a Megrelian term meaning “river that eats its way through the mountains.” That incidental definition seems to further the swelling sense of comfort that unfolds in the song. The tension of the strings mimics the uncertainty of that first touch with water, which is slowly eclipsed by the weightlessness beneath the surface, depicted in the slow notes of Portioli’s piano, and then the warmth of a voice.

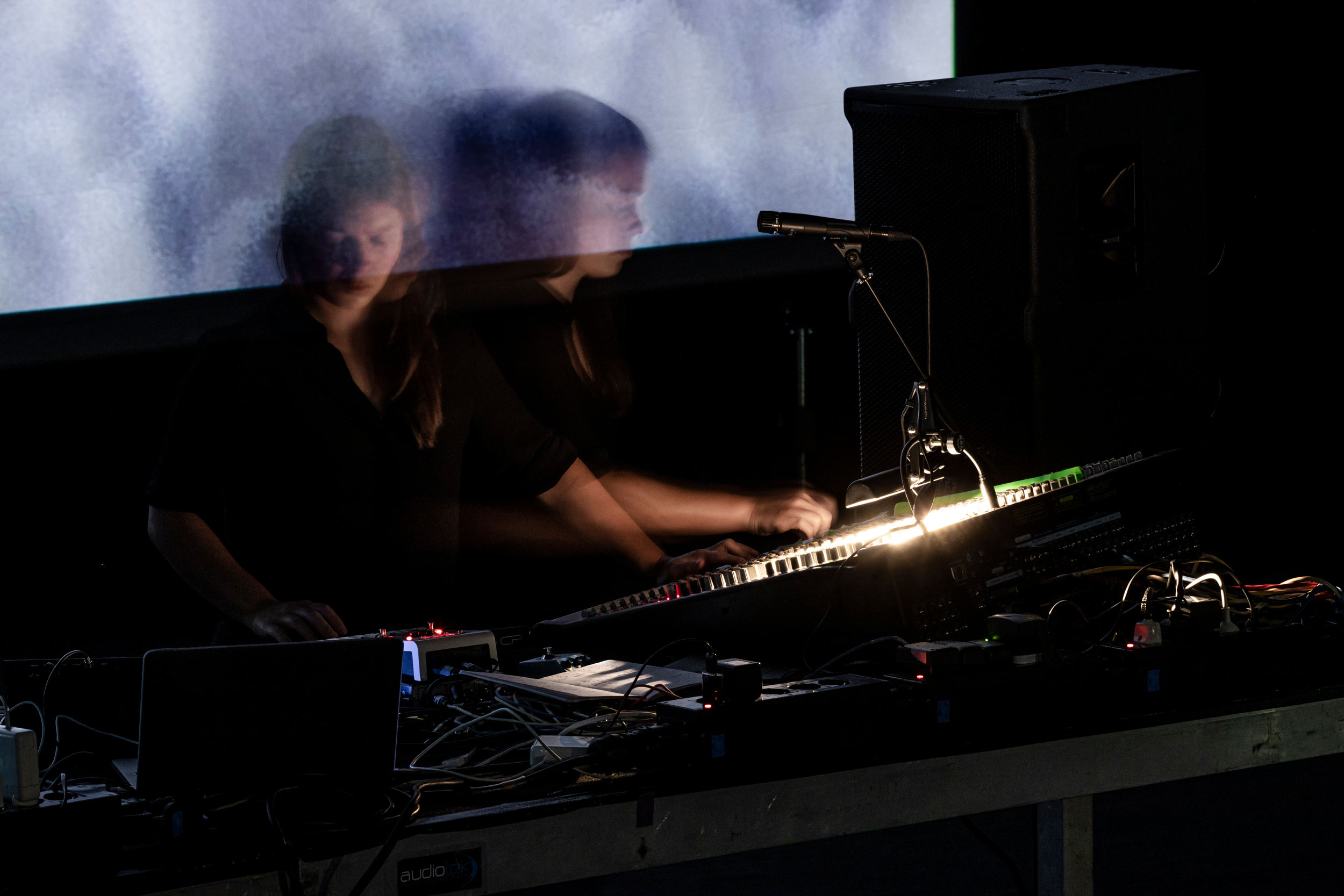

With a background in linguistics, traditional music, sound engineering, and film scoring, the Dutch-Italian composer’s practice lives across a multitude of disciplines. Portioli will make the record more immersive at Rewire in early April, incorporating live piano by Andert Tysma and light and stage design from her long-time collaborator Marco Ciceri into her performance.

Ahead of All Above’s February 24 release via Editions Mego, the artist joins Document to expound upon the evolution of Grand River, imagining emotion through sound, and why she’s insistent that her art isn’t meant to be one-way communication.

Megan Hullander: You started working on All Above more than two years ago. Has the concept for the album evolved since then?

Aimée Portioli: What happened, in practice, is that unfortunately, very sadly, Peter Rehberg died. And Peter was running the label, Editions Mego, that put out my last record. The last day that I saw him, he asked, ‘When is your next album coming?’ I was working on it, but I never got the chance to actually show him. I mean, I still hope he can somehow [listen], even if he’s not with us anymore.

The core concept didn’t really change, because [the songs] are part of one emotion that I kept throughout this time. I was somehow able to stick with this feeling that I wanted to get out of myself.

Megan: How do you go about translating a singular emotion into sound?

Aimée: Music is another language. All the work that I do—whether it’s composing an album or a piece for sound installation—is free composition. And, in the end, I’m composing an externalization of a feeling that I have. Everything that we experience—nice things, neutral things, bad things, joyful things—everything we see and everything we do, we absorb. These pieces are all moments of myself; they are expressions of emotion.

Megan: You’ve been firm that visuals aren’t a part of your songwriting practice. I’m curious as to why that’s an important clarification to make.

Aimée: I’m often told that my music has this cinematic touch to it. Of course, it’s very nice to hear that, but when I’m composing the piece, I don’t have that visual vision. For me, it’s like when a painter freely decides to paint something without a landscape in front of them, but is doing an interpretation of that landscape. It’s an expression of something that comes from the inner world, into the outside world. My inside world doesn’t really have that [visual component], unless, of course, it’s based on a memory. But it’s more personal than that.

Megan: And I know you’ve studied as a linguist—how have your understandings of language translated into your artistic philosophies, or your approach to that musical language that you referenced?

Aimée: I wrote my thesis about the communicative function of music. Before that, I was just playing in bands and impulsively composing. And then, when I stumbled into this research on the psychology [of it], I started to become more aware of what I was doing. [Before], I was doing it naturally, naïvely. We take so many things for granted in our listening process.

“I don’t like to hide between my art because I like to talk about it with people. It’s communication—and I don’t want it to be one-way. I like this exchange.”

Megan: What was the connective thread that brought these songs together for the album?

Aimée: All the pieces belong to the same world, because they all have acoustic piano. I wouldn’t say that the piano is the key instrument of the album. But it is always present in different ways. On some, it’s more airy, with reverb. On others, it’s more distorted. And on others, more clean and present, more fluid or quick.

And this album is very much tied to my home studio, because I worked on it during the pandemic. It’s more private to me.

Megan: Does it feel more vulnerable than your last albums?

Aimée: I feel a bit more vulnerable, I must say, but in a good way, in an interesting way. Vulnerable is not the right word—maybe exposed? Playing acoustic instruments is an intimate process: You can have a personal relationship with the flute, the violin, the cello, the piano, because you can just sit with them. It becomes a dialogue between you and that instrument. I integrated some acoustic instruments on my last album. And I think, this time, I brought it a bit further.

Of course, this can have a touch of vulnerability. But I don’t like to hide between my art because I like to talk about it with people. It’s communication—and I don’t want it to be one-way. I like this exchange.

Megan: Are you able to have that sort of exchange at all with yourself? Like, as you get further from past releases, do you feel like you have those conversations with your past self who wrote them?

Aimée: The further away they are in the past, the more I’ve changed—but, still, they stay a part of me. It’s a me that doesn’t exist anymore. And there are things that I still do, but it would never be possible for me to recreate exactly the same album that I did back then, because I’m not that person anymore. How does art evolve with us? I feel very close to my albums. But I’ve also noticed that they belong to another version of myself.

Megan: You mentioned that an element of further exposing yourself on this record came through the visuals. As your writing process doesn’t incorporate that visual element, what does translating that emotion into an image look like for you?

Aimée: I knew that I wanted to do something where I was part of it. And my idea was to have a picture of myself where I looked up, as a visual representation of the title of the album, [All Above]. My longtime collaborator, the visual artist Marco Ciceri, made this beautiful video in Iceland of one of the strongest and biggest waterfalls. This steam [appears] when you get close. And we used that for the cover.

I wanted to express what’s driving me, what’s affecting me. It’s untouchable, it’s something that is not there. It’s above us. And it’s bigger than us.