Following the book’s release, creative director Sander Lak joins Document to discuss the chromatic philosophy underpinning his distinctive point of view

Sander Lak has always been sensitive to color. “Growing up, I just assumed that I see colors the same way everyone sees them,” the designer says, from his bright, book-filled apartment. “I believe that some people feel colors more intensely. It’s something you cannot train—you can teach people to look at things, but they either have it or they don’t.”

This particular affinity was central to Lak’s practice as the creative director of Sies Marjan. Known for its daring, evocative palette and playful approach, the brand burst into the scene in 2016 and soon earned a cult fanbase. It’s been credited with starting a “chromatic revolution,” breathing life into New York’s often-monochromatic fashion landscape for five brief, bright years before closing its doors.

Now, Lak is paying homage to its enduring impact in The Colors of Sies Marjan, a 400-page volume published by Rizzoli. Rather than building the book around collections or seasons, its structure—and the main thrust of its inquiry—centers the subject of color itself, exploring its complicated and ever-evolving relationship with human psychology, art, and commerce. Punctuated with interviews and writing from today’s preeminent thinkers and creatives—Marc Jacobs, Donna Tartt, Isabella Rossellini, Rem Koolhaas, and Hanya Yanagihara among them—it explores the life and legacy of a brand that traversed the color spectrum.

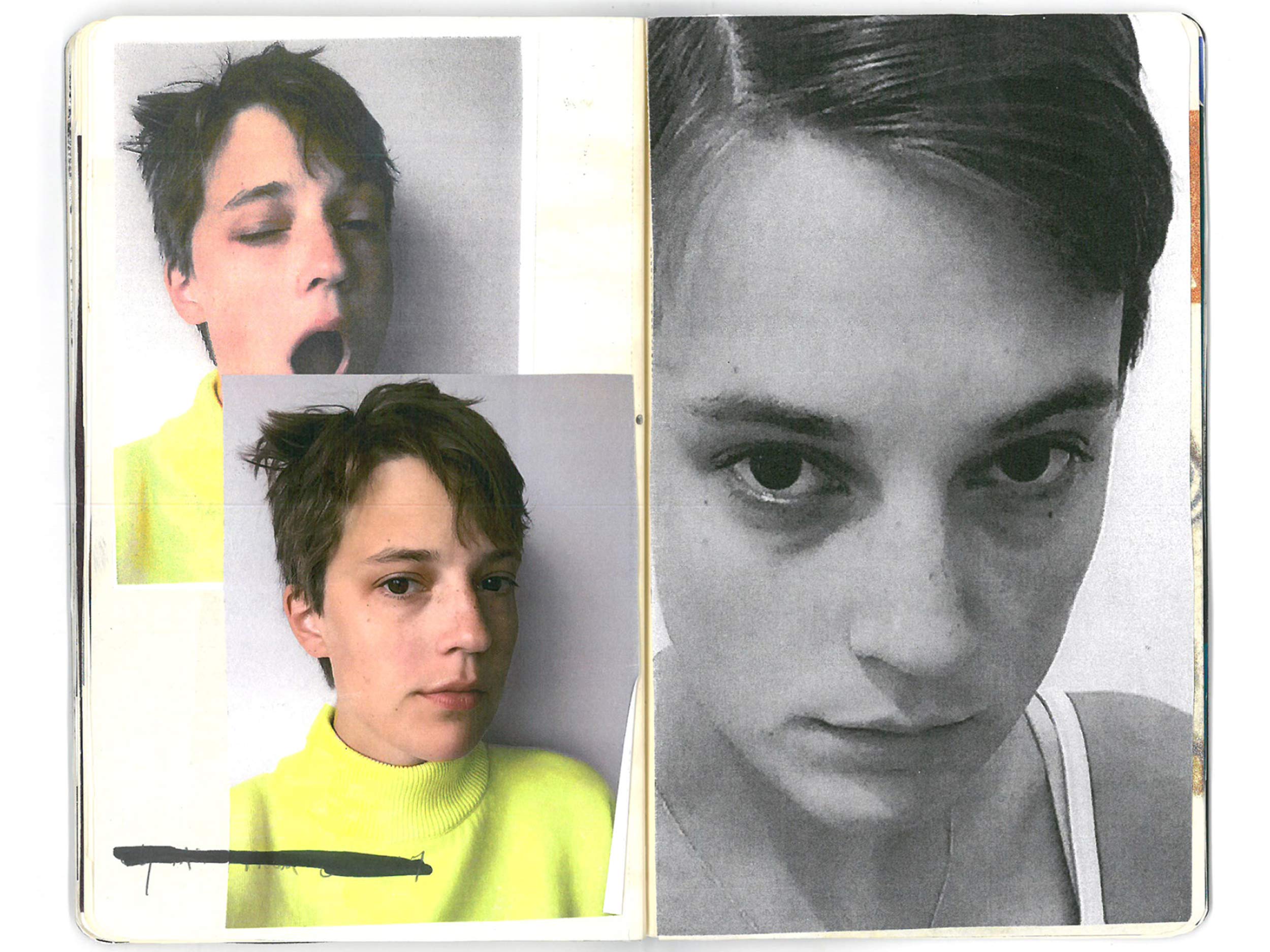

For the designer, Sies Marjan is more than a creative project—it’s a family affair. Not only does it derive its name from Lak’s parents, but it carries an intimate significance in the story of his own life. “Sies Marjan symbolized the creation of a home after being a nomad for so long,” Lak says. “And for me, the best way to close that chapter was with a book—something that documents the time that the brand was here.”

Camille Sojit Pejcha: What was the role of color in your early life?

Sander Lak: I have a real sensitivity to color early on—I just didn’t realize it was unique. I always just assumed the way I see colors is how everyone sees them. As a kid, I would organize things by color, and I would be very attuned to its effect on my mood.

My father used to work for a company that made us travel around the world, so I was born in Brunei, and lived in Asia, Africa, and Scotland. When we were in Africa, we were living in Gabon, in the middle of the rainforest. My mom used to dress me and my brothers in red, because we were surrounded by green. That’s when I started to understand the politics of color.

Did you know that it’s scientifically proven that red is the first color that your brain registers? That’s why red is such an emotional color for most people. In a more general sense, I do believe that some people feel colors more intensely. It’s something you cannot train—you can teach people to look at things, but they either have it or they don’t. And it’s not always the same—one color can provoke different emotional reactions at different times.

Camille: To you, what’s the relationship between color and form when making a garment?

Sander: For Sies Marjan, we did the color card first, and then the fabrics would be dictated by that. Knowing what the colors are, the fabric was almost a secondary ingredient. It forces you into a direction without having very clear references, and that’s what I love about color: it’s an abstract thing. Everyone has a different opinion about a color—one person might think of a childhood toy, while another thinks of the earring they bought last week. We’re talking about the same color, but there’s a completely different connection to it.

“Everyone has a different opinion about a color—one person might think of a childhood toy, while another thinks of the earring they bought last week.”

I was always playing with my own associations, which are unique to me, though they aren’t necessarily visible afterwards. I remember the third collection we did, the color cards were based on The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. But because I picked colors from the show and took them out of that context, they have nothing to do with it. I made these really luxurious, beautiful pieces out of those colors, and then shoved them back into a cheap Hilton Hotel, Trump-esque environment where we held the show, and people didn’t know exactly what the reference was, but they felt something. That’s kind of that intuitive feeling that I wanted to always provoke in people.

Camille: It sounds like you’re almost reverse-engineering what people’s personal association with color is, and then playing with that assumption.

Sander: Sometimes I’d look at the colors for Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins—such cheap, horrible colors. But when you take it out of that context, and you make a beautifully draped, silk, hand-sewn dress, part of you knows you’ve seen those colors somewhere—but you’ve never seen them in such an elevated context, so you can’t really link it consciously. It’s only afterwards, when I say it, that people are like, Oh my god!

It shows the power of color and the power of association, because you can use the same color for 50 different things and it will be different every time.

Camille: You mentioned moving around a lot growing up. Did fashion, or your use of color, help you feel more at home in certain spaces?

Sander: I was raised around the world, so the idea of home and belonging is something that I’m still not really sure about. I think that people like me, who are from families who worked as diplomats or for organizations that require travel—we all have a little bit of that same syndrome: what’s home?

Sies Marjan symbolized the creation of a home after being a nomad for so long. It was sort of what anchored me in New York. It was why I came back, and made it my home for those four or five years.

Camille: What inspired you to commemorate the brand’s impact in a book, and was there anything new you realized about your own creative process by looking at it in this way?

Sander: I realized that my method is so connected to my own gut feeling—and for Sies Marjan, it was really instinctual. But I was also doing a lot of deep thinking and research about color, and it’s interesting to see the methods people use to communicate that thing that comes so naturally to me—to translate these concepts about color to people who don’t have that instinct. If somebody asked me which shades to pair, I’d know immediately, but I couldn’t always tell you why, because I’m in my own world.