The prolific artist’s sketchbooks, letters, and press clippings—nearly lost to modern audiences—are to be digitized for public consumption, and immortalized in our cultural history

To discover an artist—and especially a 20th-century artist—who hasn’t yet been paid their dues elicits a prideful kind of joy, one that often becomes tainted by the inability to traverse works beyond their best-known. Mary Dill Henry was one of those artists. From large-scale oil paintings, to designs that elevated expectations for commercial art, to her innovative influence on the Op art movement, the scope of Henry’s career was immense, but remained largely obscured—until now, that is. A completed archive that includes sketchbooks, photographs, letters, artist statements, press clippings, and records of Henry’s professional graphic design work is now available at the artist’s alma mater, the Illinois Institute of Technology, the whole of which are to be digitized by Hauser & Wirth Institute for public consumption early next year.

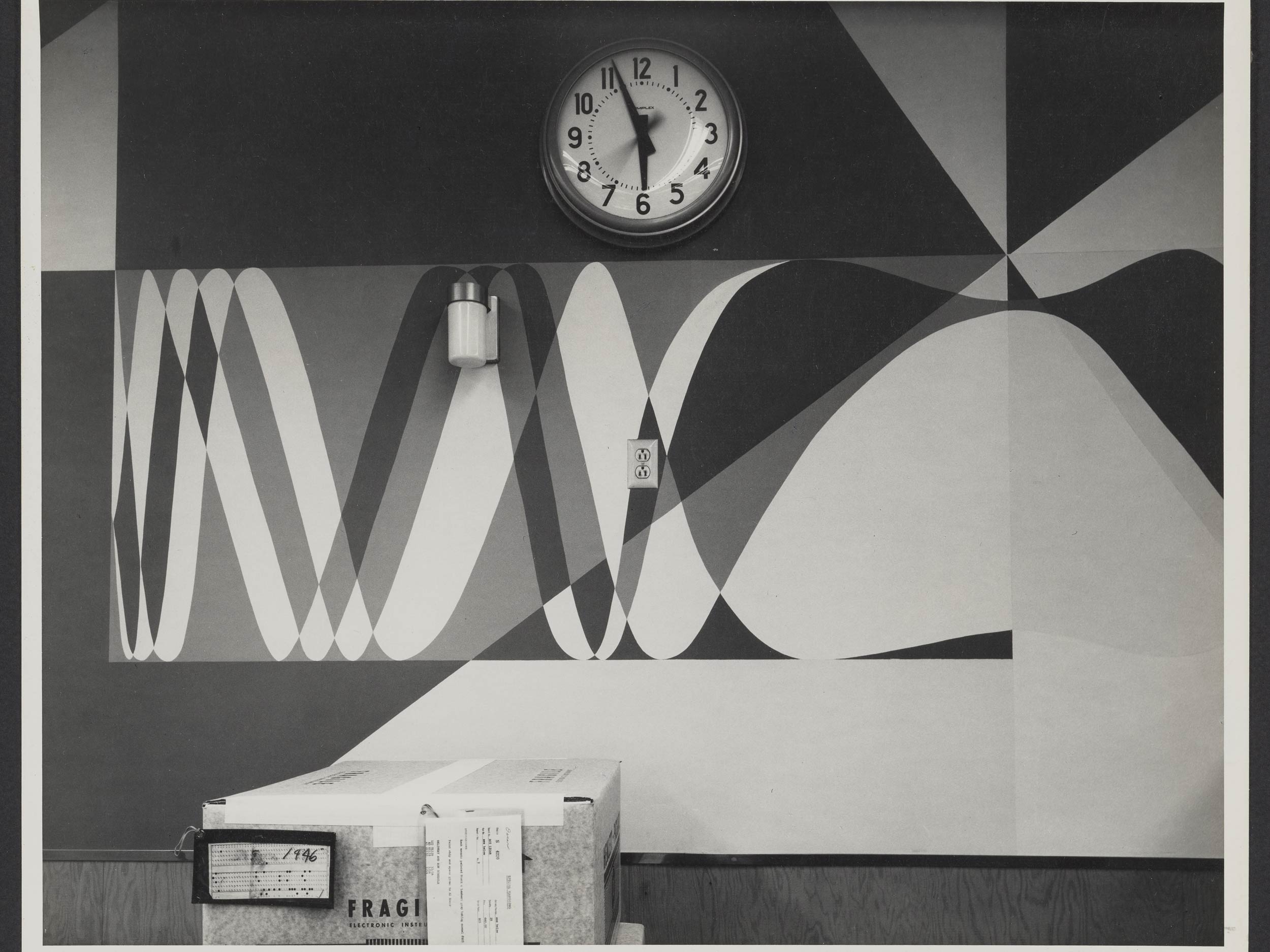

Though nearly forgotten by modern audiences, Henry’s work earned prominence in its own time: She was one of the first women invited to teach at the American Bauhaus (a position she declined to accommodate her husband’s ambitions, which required them to relocate); Hewlett-Packard commissioned her to design sprawling mosaics for its headquarters in Palo Alto (in its infancy, Silicon Valley favored blending business with Bauhaus for its architecture and interiors); and, later in her career (liberated by her divorce and the influence of a tour of Europe), Henry continued to experiment, which resulted in a series of exhibitions across the Pacific Northwest, where she resided until her death.

The trajectories of contemporary artists are easily tracked online, but with each passing year, those whose careers predated the internet are increasingly at risk of being lost, with relatives becoming more distant, and delicate archives more likely to be buried into oblivion. The process of archiving and digitizing can be expensive, and is too often reserved for those whose works are already proliferating across all corners of the internet.

“Our archives program is ‘postcustodial,’” says Hauser & Wirth Institute’s Executive Director Lisa Darms in a press release. “We do not collect, but rather see ourselves as facilitators in the process.” The archivization of works by artists like Henry builds broader grounds for grappling with cultural history, from which we build futures for researchers, artists, and the public at large. Especially amid a culture fixated on the trends and ideologies of the past, it’s invigorating to uncover something new within them—a different branch of thought to follow in a sea of hyper-referenced names.